|

"THE FATE OF A COUNTRY"

The Repulse of Longstreet's Assault by the Army of the Potomac

D. Scott Hartwig

On July 3, 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee

conceived a plan to shatter the center of the Union Army of the

Potomac's position at Gettysburg, with a massive artillery-infantry

attack. The target was the open, exposed ground of Cemetery Ridge. Lee's

plan was wonderfully simple; he would apply overwhelming firepower upon

the point of attack by first subjecting the Union defenders to the

heaviest artillery bombardment yet seen in the war, then strike the

disorganized and demoralized defenders with an infantry force of over

13,000 troops, including Wilcox and Lang.

Since the attack failed it has been suggested that it

never really had any chance at all to succeed. But two months earlier at

Chancellorsville, Lee had seen his infantry, supported by considerably

less artillery fire, attack and dislodge Union soldiers from strong

entrenchments. The Federal soldiers on Cemetery Ridge had little cover

or prepared defenses, and many of the regiments and batteries entrusted

with defending this critical sector had suffered dreadful losses on July

2. Besides the battle casualties, the Union soldiers were worn down by

the severe marches they had made in the days before the battle.

Lee gambled that he could duplicate the feat of

Chancellorsville at Gettysburg. Past experience justified his decision.

Every major attack his army had mounted against the Army of the Potomac

had succeeded, except at Malvern Hill. His grand assault failed at

Gettysburg, not because it was doomed to failure at its inception, or

because the Federals' advantage of position was too great, or Southern

leadership faltered. It failed because the defenders of Cemetery Ridge

refused to be defeated, and fought with a spirit and tenacity they had

not exhibited on previous battlefields. "I do not believe there was a

soldier in the regiment, that did not feel that he had more courage to

meet the enemy at Gettysburg, than upon any field of battle in which we

had as yet been engaged," wrote Anthony McDermott, of the 69th

Pennsylvania Infantry.

This is the story of the Union defenders of Cemetery

Ridge, and how they triumphed at the crucial moment on July 3 at

Gettysburg. [1]

Although Union commander, Major General George G.

Meade, expressed the opinion on the night of July 2 that Lee would

attack his center the next day, he did not reinforce this area. [2] His army's strength remained concentrated on its flanks

on July 3. Meade probably reasoned that with his interior lines he could

reinforce his center if it was assailed more rapidly than he could one

of his flanks.

There were eight infantry brigades in three divisions

defending Cemetery Ridge.

Elements of two divisions of Major General Winfield

S. Hancock's Second Corps, the 2nd and 3rd, commanded by Brigadier

General John Gibbon and Brigadier General Alexander Hays, respectively,

occupied a front extending from Ziegler's Grove, a woodlot that

dominated the northern end of the ridge, south along the ridge for

slightly less than 2,000 feet.

The left of the 2nd Division rested about 500 feet

south of the clump of trees.

|

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

On their left, the 3rd Division, First Corps,

commanded by Major General Abner Doubleday, extended the infantry line

approximately another 700-800 feet south before it ended in the low

ground on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge. They had been inserted

into the front line on the evening of July 2, when a huge gap in the

Second Corps front had been created by the departure of Caldwell's

Division to the Wheatfield, and Harrow's Brigade had been dispersed to

various hot spots.

All three of these divisions had already participated

in severe fighting - Doubleday's on July 1, and Gibbon's and Hays' on

July 2 - and had suffered heavy casualties. Two of Doubleday's brigades,

Colonel Roy Stone's and Colonel Chapman Biddle's, could muster only

approximately 440 men each. Nearly two-thirds of the men in these

brigades had been shot or captured on July 1.

Doubleday's third brigade, Brigadier General George

J. Stannard's, consisted of three big nine-month Vermont regiments, each

numbering 600-700 officers and men. They had arrived late on July 1 and

had been spared the slaughter experienced by Stone's and Biddle's

regiments. Although the regiments were well-drilled, they had never

experienced combat. They did well enough on July 2, when ordered to

regain guns and ground lost to Richard H. Anderson's Division, but

Anderson's attack had spent itself by the time Stannard's men arrived,

and the Confederates did not put up serious resistance to the

Vermonters' advance. Stannard's nine-monthers had yet to experience the

ferocity of an attack by fresh troops of the Army of Northern Virginia.

[3]

The three brigades of Gibbon's division had been

pressed hard by Anderson's attack on July 2. The regiments of Brigadier

General William Harrow's brigade, on the left of the division, in action

at various points lost almost 500 men out of a brigade strength of

approximately 1,360. The famous 1st Minnesota lost over sixty per-cent

of its strength, including all of its field officers, in a desperate

charge to check the advance of Wilcox's Alabama Brigade. They numbered a

mere 70 effectives on July 3, and this only because Company L, which had

been on provost duty on July 2, returned to the regiment. The 82nd New

York and 15th Massachusetts were virtually run over by Wright's Georgia

Brigade at the Nicholas Codori farm on the Emmitsburg Road, where they

were attempting to bolster the right end of the Third Corps line. The

82nd lost 143 men; the 15th did not record their losses for July 2, but

they were probably about the same as the New Yorkers. Colonel Francis

Heath's 19th Maine lost 130 men in helping coer the retreat of

Humphrey's Division of the Third Corps. [4]

Gibbon's other two brigades, Colonel Norman Hall's

and Brigadier General Alexander Webb's, helped repulse the attack of

Wright's Georgians on the 2nd. Casualties had been relatively light, but

most of the regiments in these two brigades were slim to start with, the

results of hard fighting and campaigning since the spring of 1862.

Hall's largest regiment was the 20th Massachusetts, with approximately

240 effectives. Every other regiment in his brigade was under 200

officers and men. Webb's greatest loss came by detachment. The 106th and

71st Pennsylvania were both detached on the evening of July 2; the 106th

to East Cemetery Hill, and the 71st to Culp's Hill. The 106th, except

for two companies on a skirmish line, remained detached on July 3. The

71st returned. They had no orders to do so, but their colonel, R. Penn

Smith, confused by the fluid situation that existed on Culp's Hill on

the evening of the 2nd, and a perceived lack of support that cost his

regiment 14 men, simply marched his command back to Cemetery. [5]

On Gibbon's right, Alexander Hays had two of his

division's three brigades available. Colonel Samuel S. Carroll's veteran

brigade, except the 8th Ohio, which was on the division skirmish line,

was sent to East Cemetery Hill on the evening of the 2nd, where they

helped repulse the attack of Early's Division. They remained there on

the 3rd to provide support to the Federal artillery, and bolster the

shaky remnants of Ames' division, of the Eleventh Corps.

Hays' remaining two brigades were commanded by

Colonel Thomas A. Smyth, and Colonel Eliakim Sherrill. Three of Smyth's

four regiments, the 1st Delaware, 14th Connecticut, and 12th New Jersey,

took part in severe skirmishing that swirled about the William Bliss

farm, midway between Cemetery Ridge and Seminary Ridge, on both July 2,

and the morning of the 3rd. It cost the brigade 74 casualties. By

Gettysburg standards the losses were not heavy but they left the already

understrength 1st Delaware and 14th Connecticut both with less than 200

effectives on July 3. The 12th New Jersey, a huge regiment by the

standards of the veteran Second Corps, numbering approximately 370,

helped beef-up Smyth's line. [6]

Sherrill's brigade of four New York regiments was

also detached on the late afternoon of July 2 to reinforce a gaping hole

formally held by elements of the Third Corps. Colonel George Willard, a

gallant and skillful officer commanded the brigade then, and he led them

up against Barksdale's tough brigade of Mississippians. The steam had

largely gone out of Barksdale's attack when Willard's New Yorkers

counterattacked. A bloody fight ensued, in which the Mississippians were

checked and forced to retreat. But nearly 450 men of Willard's brigade

were shot, and Willard was killed by a shell while reforming his

command. [7]

The strength of this infantry line on Cemetery Ridge

can only be estimated. Certainly, it did not exceed 7,000 effectives and

the true strength was probably around 6,500. Nearly all of them were

jaded and bloodied. "They looked like an army of rag gatherers,"

observed Lieutenant Frank Haskall, a staff officer to General Gibbon,

"for you know that rain and mud in conjunction have not had the

effects to make them very clean." Sergeant James Wright, of the

battered 1st Minnesota, wrote that, "Stains of powder and

dirt...still covered our hands, faces and clothing...and physical

weariness and mental depression and suffering was written on every

countenance."

It is difficult to convey the mental and physical

fatigue experienced by most of the Federal infantrymen on that ridge.

Few people in their lifetime ever endure anything remotely like it.

Combat saps the human body of its strength. Yet, these infantrymen were

not even permitted the minor luxury of hot coffee, food, and sleep.

Fires were forbidden, few regiments had any rations, and most men were

too busy strengthening their position or helping evacuate casualties to

catch more than the briefest rest. The defenders might have adopted the

attitude that they had done their part; it was time for someone else to

take their turn. Certainly, the 1st Minnesota Infantry had earned that

right, but as Sergeant Wright noted, under ordinary circumstances the

regiment would have been relieved, "but this was no ordinary

occasion," and "it was believed that every available man and gun

would be needed for the defense of the ridge." [8]

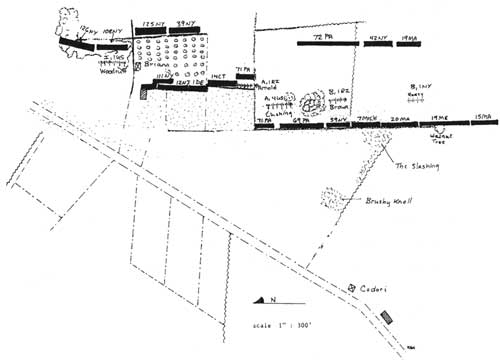

The infantry were supported by plentiful artillery.

The front of the two Second Corps divisions were covered by the five

batteries of the Corps' artillery brigade, commanded by Captain John

Hazard.

In Zeigler's Grove were the six 12-pound Napoleons of

Lieutenant George A. Woodruff's Battery I, 1st United States

Artillery.

Two hundred yards south of Woodruff, Captain William

A. Arnold's Battery A, 1st Rhode Island Artillery (six 3-inch rifles),

were positioned behind a stone wall.

On Arnold's immediate left, and within the area that

would become known as "The Angle," were six more 3-inch rifles of

Lieutenant Alonzo Gushing's Battery A, 4th United States Artillery.

Four Napoleons of Brown's Battery B, 1st Rhode Island

Artillery stood just south of the Clump of Trees. Captain Brown had been

wounded on July 2 and Lieutenant Walter Perrin had assumed command.

One hundred fifty yards south of Perrin's guns were

four 10-pound Parrott rifles of Captain James Rorty's Battery B, 1st New

York Artillery. [9]

Considerable additional artillery were positioned

where their guns could cover the open ground between Cemetery Ridge and

Seminary Ridge.

Throughout the morning of July 3, the Union Chief of

Artillery, Brigadier General Henry J. Hunt, and Lieutenant Colonel

Freeman McGilvery, commanding the 1st Volunteer Brigade of the Reserve

Artillery, assembled a powerful line of artillery about 250-300 yards to

the left and rear of Stannard's brigade, extending south along an

extension of Cemetery Ridge for nearly 400 yards. Parts of nine

batteries, many of which had suffered severely on July 2, made up this

line, which counted 20 Napoleons, 13 3-inch rifles, 4 James rifles, and

2 12-pound howitzers - 39 guns in all. McGilvery's line, as it came to

be called, could punish any troops advancing over the open ground south

of the Codori Farm toward Doubleday, Harrow or Hall, with an oblique,

and possibly enfilading fire of shrapnel and shell. Beyond Hall's front,

his guns could not fire effectively. [10]

Two other batteries contributed to the firepower that

could be brought to bear on the southern half of the Cemetery Ridge

line. The 9th Michigan Horse Artillery (six 3-inch rifles), commanded by

Captain Jabez J. Daniels, took position a short distance to the right

and front of McGilvery's line. On Little Round Top, Lieutenant Benjamin

Rittenhouse had six 10-pound Parrott rifles of Battery D, 5th U.S.

Artillery, that could deliver fire, although at long range, across all

of Doubleday's and Gibbon's front. [11]

Alexander Hays' division could count on the support

of nearly 38 guns on Cemetery Hill, under the direction of Major Thomas

W. Osborne, the Eleventh Corps' artillery chief. These batteries could

strike any force advancing on Hays' front from Seminary Ridge to about

the Emmitsburg Road. If the enemy managed to advance beyond this point,

Osborne's batteries could not safely fire upon them without endangering

Hays' infantry with short rounds. [12]

Besides the batteries on the front line, Hunt could

draw upon the remainder of the reserve artillery and the Sixth Corps

artillery brigade, to strengthen a threatened point, or relieve damaged

batteries.

Although it enjoyed deadly fields of fire, the

Cemetery Ridge line had its weaknesses, which Wright's attack on July 2

had partially revealed. Apart from Zeigler's Grove, which offered some

cover and concealment, the defenders, particularly the artillery, were

greatly exposed to artillery fire. The western slope of the ridge was

gentle, descending only about 20 feet from the Clump of Trees to the

Emmitsburg Road, and there were few obstructions to break up enemy

attack formations. The left end of the infantry line, where Doubleday's

regiments were posted, was on lower ground than that occupied by

Gibbon's and Hays's divisions, and was commanded by the high ground

extending from the Peach Orchard to the Rogers Farm.

The infantry force assigned to defend this sector of

the Union front, as related earlier, was thin compared to what Meade had

massed on his flanks. Hays and Doubleday both had some depth to their

lines, but in Hays' case, his reserve line consisted of Sherrill's

bloodied brigade, which probably numbered less than 1,000 officers and

men. Doubleday had Stone's and one-half of Biddle's brigade's in his

support line, which combined barely equalled the strength of one of

Stannard's regiments. Gibbon's line was the slimmest. The heavy

casualties incurred on July 2 forced him to place all but three of his

regiments on the front line. In reserve were the 19th Massachusetts,

42nd New York, and 72nd Pennsylvania. The 72nd was a comparatively

strong regiment, numbering approximately 380 effectives, but the 19th

and 42nd both counted less than 200 men in their ranks. Gibbon also held

the most vulnerable part of the line - what would become known afterward

as The Angle. [13]

The Angle had been created not by Union soldiers, but

by the people who had farmed this land for generations before. The

abundant boulders the farmers plows turned up were put to use to define

field and property boundaries. From Abraham Brian's barn, on Hays's

front, a stone wall generally followed the crest of Cemetery Ridge for

slightly over 200 yards. Here it turned 90 degrees and ran west for

about 70 yards, where, upon a rock outcropping, it made a second

90-degree turn south. This point was The Angle. From this outcropping

the wall continued south for approximately 260 yards before it stopped.

Although the walls were only about two to three feet in height, Hays's

and Gibbon's soldiers used them as ready-made protection, improving them

slightly by dismantling the rail fencing that rode over the walls and

stacking the rails on the walls. But The Angle created a prominent

salient on the Cemetery Ridge that, as we shall see, posed a knotty

tactical problem for the infantry officers tasked with its defense. [14]

There were several other features along Gibbon's

front that created potential problems. The famous Clump of Trees was

actually a cluster of trees and brush that had taken root in thin rocky

soil that could not be tilled. When Gibbon's soldiers arrived on July 2,

the trees of this clump spread down the western slope of the ridge to

the stone wall and south along the stone wall until a gap in the wall

was reached, located about 100 yards south of The Angle. The gap was

merely an access point for farm equipment. About 70 yards south of this

gateway a rail fence departed from the stone wall, running in a

northwesterly direction to the Emmitsburg Road.

Brush and small trees had also grown up along this

fence and at two small knolls, or rock outcroppings, adjacent to the

fence, and in front of Gibbon's main line. The first of these knolls is

directly in front of the position held by the 7th Michigan. The second

is about 100 yards west of the first. This second outcropping offered

defilade and a fine firing position for riflemen if it could be reached

by the enemy. The brush on this outcropping and the other, and along the

stone wall, obstructed the field of fire of Cushing's and Brown's

batteries and details cut them down. The cuttings were not removed,

creating a slashing of cut brush and small trees along the rail fence

and at these knolls. The brush removed from the wall was tossed in rear

of the line of battle. Robert Whittick, of the 69th Pennsylvania,

positioned directly in front of the Clump of Trees, recalled that within

eight or ten feet in rear of his regiment, "it was all cut down,"

and the cuttings were thick enough to create some difficulty in

movement. [15]

Following the near success of Wright's Brigade on

July 2, most of Gibbon's regiments had labored through the night to

improve their meager protection. Colonel Norman Hall reported that

during the night his brigade strengthened its position "as much as

possible with rails, stones, and earth thrown up with sticks and boards,

no tool being obtainable."

James Wright, of the 1st Minnesota, recalled his

comrades "gathered rails, stones, sticks, brush, &c., which we

piled in front of us; loosened the dirt with our bayonets and scooped it

onto these with our tin plates and onto this we placed our knapsacks and

blankets."

The quality of the works thrown up apparently

depended upon the unit leadership and the quantity of tools and

materials that were handy. Tools were in particularly short supply.

Captain Henry L. Abbott, of the 20th Massachusetts reported that there

was only a single shovel for the entire regiment, with which they dug

"a slight rifle-pit, afoot deep and foot high." The 69th

Pennsylvania evidently did not put the same energy into improving their

cover, for General Webb observed in his after-action report that the

"cover in its front was not well built." Stannard's men collected

rails "where the dividing lines of the fields had run" and

stacked them in their front for a breastwork, which George Benedict on

Stannard's staff noted "sufficed for a low protection of from two to

three fret in height." [16]

Besides building up breastworks to stop a bullet or

shell fragment, some regiments used the cover of night on July 2, to

collect small arms and ammunition from the fallen Union and Confederate

soldiers in front. The 69th and 71st Pennsylvania were particularly

noteworthy in this enterprise. Colonel Robert P. Smith, of the 71st, had

the rifles and muskets his men collected gathered into a pile, but there

were enough to equip several companies with three to one dozen muskets

to a man. Robert Whittick, of the 69th, stated that his regiment

gathered enough small arms to arm each man with between six to twelve

rifles or muskets. The adjacent 59th New York also hauled in a large

number of small arms. The other regiments along Gibbon's front probably

did likewise, but the evidence indicates these three regiments scavenged

the lion's share. They would need them. [17]

The infantry regiments and batteries were deployed

along the ridgeline in mutual support of one another.

Lieutenant George Woodruff's Battery I, 5th U.S.

Artillery, supported by the 108th New York of Colonel Thomas A. Smyth's

brigade, held the far right end of the line, although later in the

morning Hays moved the 126th New York into line on the battery's

right.

The rest of Smyth's regiments filled the space

between the barn of Abraham Brian and Captain William A. Arnold's

Battery A, 1st Rhode Island. From right to left, they were the 12th New

Jersey, 1st Delaware, and 14th Connecticut. Sherrill's four New York

regiments, the 126th, 111th, 125th, and 39th, from right to left, lay in

support, sheltered partially by Brian's orchard, and, for the right of

the 126th, Zeigler's Grove.

To the left of Arnold's guns was The Angle, the

defense of which was entrusted to Webb's brigade and Cushing's battery.

The 69th were deployed with their left near the farm access gate, which

was defended by the 59th New York, and their right extending to about 40

paces from the angle. This space was filled by the left wing of the 71st

Pennsylvania, all that could fit. The right wing of this regiment lay to

their rear, along the recessed portion of the stone wall, between

Arnold's and Cushing's batteries.

One hundred fifty feet in rear of the 69th and left

wing of the 71st were Cushing's guns. In their rear, and behind the

reverse slope of Cemetery Ridge, Webb placed his strongest regiment, the

72nd Pennsylvania, 380 effectives, as a reserve.

The vulnerable point of Webb's line was The Angle.

There simply was no easy way to defend a position at right angles. No

one could be placed along the east-west connecting wall for they would

present their flank to the enemy line. This left the right flank of the

71st's left wing exposed. They would have to rely upon the firepower of

their comrades of the right wing, Arnold's battery, and the 14th

Connecticut, along the recessed wall, to protect their flank. [18]

On Webb's left, Colonel Norman Hall, placed three

regiments of his brigade in the front line. From right to left they were

the 59th New York, 7th Michigan, and 20th Massachusetts. The 59th, which

numbered only about 150 men consolidated into four companies, drew the

most difficult assignment: guarding the farm gate. But they had plenty

of firepower backing them up. The four Napoleons of Battery B, 1st Rhode

Island stood in their rear, at the crest of the ridge, south of the

Clump of Trees, their tubes positioned to fire over the New Yorkers.

Hall remaining regiments, the 19th Massachusetts and 42nd New York, were

placed in rear of Brown as a support and reserve.

The heavy losses incurred on by Harrow's brigade July

2 had left its Norman Hall regiments so reduced that they could afford

no reserve, and the entire brigade were on the front line. From right to

left they were, the 82nd New York, 19th Maine, 1st Minnesota, and 15th

Massachusetts. In rear of the 15th Massachusetts and 82nd New York, were

Captain James Rorty's four guns. On Harrow's left were the two tiny

First Corps regiments of Biddle's brigade, the 20th New York State

Militia and 151st Pennsylvania, under the command of the 20th's Colonel,

Theodore B. Gates. About 100 yards in their rear, Doubleday positioned

his reserve in two separate lines, Stone's brigade in the first and the

remainder of Biddle's in the second. [19]

Stannard's brigade of Vermonters initially were

deployed along the same line as Gates, Harrow and Hall, behind what

Ralph Sturtevant, of the 13th Vermont, described as a "tumbled down

stone wall in our front." Stannard had two regiments on line, the

13th on the right and 14th on the left. The 16th Vermont were detailed

to the skirmish line, covering the front of Doubleday's division. Their

colonel, Wheelock G. Veazey, placed three companies along with some

details from other regiments, out as skirmishers, extending from just

north of the Codori farm south-southeast along the slight ravine cut by

the headwaters of Plum Run for several hundred yards, until they met the

skirmish line of the Fifth Corps. The remainder of the 16th formed the

picket reserve about 100 yards in advance of the brigade line of battle.

[20]

At daylight on July 3, A. P. Hill's Corps artillery

commenced lobbing shells at Union battery positions along Cemetery

Ridge. Various batteries responded to this fire, and early in this

artillery exchange and a Confederate shell struck a caisson of Thomas's

battery and blew it up, killing and wounding a number of men in the

nearby 14th Vermont. To protect this regiment from any more such losses,

General Stannard, ordered the 14th to move forward about 50 or 60 yards.

According to George Benedict, the 14th's right lay in front of Codori

spring, and a sluggish stream ran in rear of the regiment. There were

scattered trees and bushes throughout this marshy area, which afforded

the Vermonters some cover from enemy observation. [21]

Later that morning, Lieutenant Albert Clark,

commanding Company G, of the 13th Vermont, pointed out to his regimental

commander, Colonel Francis V. Randall, that a rail fence nearby could be

torn down and a breastwork constructed along a small tree covered knoll,

about thirty or forty yards in front of the regiment's position. This is

the knoll upon which General Hancock would be wounded that afternoon.

Randall approved the lieutenant's proposal and Clark called out for

volunteers to do the dangerous work.

Sharpshooters were an ever-present and deadly danger

to anyone who needlessly exposed themselves, so volunteering for Clark's

work detail was not for the faint of heart. Sergeant George H. Scott, of

Clark's company, was the first to answer his lieutenant's call. About

twenty other hardy souls also offered themselves, and led by Sergeant

Scott they charged the rail fence, tore it apart, and carried the rails

forward to the line indicated by Lieutenant Clark. "The work was

quickly and well done and timely," wrote the regimental historian,

and fortunately was completed with no casualties. The breastwork stood

about two feet high, extending across the tree covered knoll. The

regiment did not occupy this advanced position immediately. The works

apparently were built to be manned only if the enemy made an attack in

the brigade front, for from this knoll the regiment would have an

excellent field of fire of the open ground extending to the Emmitsburg

Road. [22]

This activity on Stannard's front left his regiments

deployed in a staggered, or en-echlon front, with the main body of the

16th Vermont line nearly 100 yards in advance of the mainline. The 14th

Vermont lay about 30 yards to their right and rear, their line being

south of the tree covered knoll previously mentioned. Sixty to 70 yards

to the rear and right of the 14th, was the 13th Vermont. This was not an

ideal brigade deployment, and the brigade position, except for the

wooded knoll, had few defensive benefits, being commanded by the

Confederate positions along the Emmitsburg Road ridge and Peach Orchard.

However, Stannard's position fell within the front commanded by Second

Corps commander Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, and he voiced no

objection to the position of the Vermonter's three big regiments, so we

must presume that they had been posted as well as circumstances and

terrain permitted. [23]

WHAT MANNER OF MEN

The defenders of Cemetery Ridge were a fair sampling

of the manhood drawn to defend the Union from New England, the

mid-Atlantic states, and the upper midwest. They ranged from Harvard

graduates to Irish immigrants. There were professional soldiers,

fishermen, laborers, farmers, millworkers, clerks, plumbers, bartenders,

students, seamen, and a host of others, who now wore the Union blue and

gazed across the open space toward the distant trees of Seminary Ridge,

waiting for what their foe might be planning. Although the elite of

society were represented in the ranks, most of the men belonged to the

common class: average people thrust into exceptional circumstances. They

were men like Benjamin Falls, James Wilbur, Hugh Bradley, and Henry

Ropes. They were part of the now anonymous mass of soldiers whose names

have faded into the mists of history, but the fate of the nation rested

upon their likes.

Falls had been a seamen before the war. He enlisted

in Company A, 19th Massachusetts, at age 36. Wilbur had been born in

Canada, but migrated to Vermont, where at age 45 he enlisted in Company

C, 13th Vermont. His age, and that of Falls, was not unusual in the

largely volunteer army that made up the Army of the Potomac at

Gettysburg. Hugh Bradley, of Company G, 69th Pennsylvania, had

immigrated from Ireland and scraped out a living as a laborer in the

Philadelphia area before he enlisted in 1861. There were hundreds like

Bradley on Cemetery Ridge, immigrants principally from Ireland or

Germany, who now fought to preserve the Union of their adopted nation.

In the 20th Massachusetts, Company K was commanded by Lieutenant Henry

Ropes, a 23-year old Harvard graduate, whom the major of the regiment

described as "one of the purest-minded, noblest, most generous men I

ever knew." Colonel Norman Hall said that of everyone he knew in the

army, Henry Ropes "was the only one he knew that was fighting simply

from patriotism."

Twenty-three year old Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing,

commanding Battery A, 4th United States Artillery, was less than two

years out of West Point. The battlefields of the Civil War were the grim

proving grounds for young professional officers like him. If they did

well and survived, it might mean promotion and a good position in the

post-war army. [24]

Each man on the ridge had his own unique story and

reason for being there. If Colonel Hall's statement about Henry Ropes is

accurate, then relatively few were there purely out of patriotism. Most

were probably like Corporal Sereno W. Gould, of the 13th Vermont. He was

39 years old and "a robust, well preserved man." But, according

to comrade Ralph Sturtevant, Gould "was no brag, nor did he court

danger or opportunity to demonstrate prowess on the battlefield. It was

evident from his general appearance and careful speech he would not run

at the sound of the first cannon or retreat until ordered. He

volunteered because his country called and for no other reason."

There were no heroes on Cemetery Ridge, merely men ready to do their

duty.

Most men were like Gould, unwilling to court danger

unnecessarily but equally unwilling to let their comrades down. One such

was a Sergeant Armstrong, of Woodruff's Battery I, 5th U.S. Artillery. A

gun in the battery had been disabled on July 2, and Woodruff sent it to

the rear with the sergeant with orders to have the gun tube dismounted

and the damaged carriage abandoned. Armstrong and his detachment found a

forge nearly 12 miles in rear of the front lines. Using the tools and

equipment available he had the carriage repaired and started back for

the front. "What was our surprise on the forenoon of July third to

see Sergeant Armstrong return to the line of battle with his piece

repaired and ready for action," recalled Lieutenant Tully McRea.

Armstrong symbolized the spirit of the Cemetery Ridge defenders. As

McRae observed, Armstrong and his detachment could have honorably

avoided the fighting on July 3, for they had orders to do so. "But

they were not of that kind," wrote McRae, and every man of the

detachment reported back for duty. [26]

Some of the defenders would not possess the courage

to face the coming storm. Either worn down by too much combat or simply

lacking in nerve, they would abandon their comrades when the crisis

arrived. Others, in contrast, would find something within them that

propelled them to extreme acts of heroism and bravery they never

imagined they were capable of.

Gibbon's division, as an organization, contained the

most experienced troops on the ridge. Seasoned veterans of every

campaign of the Army of the Potomac, except Second Manassas, they had

seen some of the most ferocious combat experienced by any troops in the

war. At Antietam, the Division, then commanded by John Sedgwick, lost

2,200 men in approximately 20 minutes. At Fredericksburg, the 19th

Massachusetts and 7th Michigan made the dangerous crossing of the

Rappahannock in boats that established a bridgehead on the south bank.

Then the 20th Massachusetts cleared the city of Barksdale's tough

Mississippians in costly street fighting. Later in the day the division

participated in the bloody and unsuccessful assaults on Marye's Heights.

Such combat takes a toll both physically and mentally. Morale in some

units had slipped. This, however, was largely dependent upon the

leadership, or lack thereof, that existed.

Some units, despite incredible casualties, maintained

a very high esprit and discipline. Others did not. Apparently, General

Gibbon believed this to be the case with the Philadelphia Brigade.

Through most of the Gettysburg Campaign they were commanded by Brigadier

General J. T. Owen, an officer popular with the brigade, but who

evidently did not run a tight ship, for his brigade earned a reputation

for being unruly and straggling badly on the march. When Owen made some

trivial breach of military policy several days before the battle, Gibbon

placed him under arrest and had Alexander Webb inserted in his place.

Although he had never commanded line troops, Webb had a reputation of

being a solid disciplinarian. He found upon assuming command on June 23

that the officers in the brigade had removed their insignia of rank, so

that they would be less conspicuous in combat. Although this became

common for officers in the First and Second World Wars, Webb thought it

reflected upon discipline and leadership, and he made the officers

restore their shoulder strap. He also issued stem orders against

straggling. [27]

The two brigades of Hays' division were both veteran

units, but their backgrounds differed greatly. The regiments of both had

been raised in the summer of 1862 in response to Lincoln's call for

300,000 volunteers that followed McClellan's failed Peninsula Campaign.

Smyth's Brigade had been formed in September, 1862, and Antietam was its

first battle. They stormed the infamous "bloody lane" there and suffered

dreadful losses. Then came Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville.

Sherrill's brigade had an unhappier background. All of its regiments had

been part of the Union garrison at Harper's Ferry when it was surrounded

by Stonewall Jackson during the Maryland Campaign in September, 1862.

All four regiments suffered the humiliation of the garrison's surrender

to Jackson, the largest capitulation of U.S. forces in the war.

Following the surrender the regiments were shipped

off to Camp Douglas, near Chicago, where they awaited their parole.

Morale plunged. They were dubbed the "Harper's Ferry Cowards," although

inept leadership and inexperience, not cowardice, had led to the debacle

at Harper's Ferry. In the November, 1862 they were finally paroled and

assigned to the defenses of Washington, where it was hoped discipline

and drill might be restored to the demoralized regiments. But though the

men's morale suffered, their fighting spirit did not flag, and they

sought the opportunity to restore their tarnished reputation. Lee's

northern invasion provided them with that opportunity.

When the Army of the Potomac marched north, the four

regiments, now brigaded together, were attached to the 3rd Division,

Second Corps. On July 2 they put to rest the hated label of "Harper's

Ferry Cowards" with their counterattacks against Barksdale's Brigade.

They proved their mettle, although at a terrible cost. [28]

The artillery batteries of the Second Corps stood

with the best in the army. All had extensive combat experience and were

led by officers of proven courage and ability.

Doubleday's division, like Hays' division, contained

troops of widely differing levels of experience. The 20th New York State

Militia was the oldest regiment of the lot. They had fought through

every campaign since Second Manassas, but they were a three-year

volunteer regiment, and the other regiments of their original brigade

were two-year volunteers. Following Chancellorsville, the rest of the

brigade went home at the expiration of their term of service. With their

brigade dissolved, the 20th were assigned provost guard duty until the

eve of Gettysburg, when they were assigned to Chapman Biddle's brigade

of Pennsylvania regiments. Biddle's regiments, like those of Colonel Roy

Stone's brigade, were raised in the late summer and early fall of 1862.

They participated in the Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville campaigns,

but saw little or no combat. July 1 at Gettysburg was their first real

battle and they fought magnificently, but at a horrendous cost.

Stannard's Vermont brigade were recruited at the same

time Biddle's and Stone's Pennsylvanians were, but by the luck of the

draw they had ended up in the defenses of Washington. Here General

Stannard turned his civilians into soldiers with a steady dose of drill

and discipline. Stannard had commanded the 9th Vermont Infantry during

the Harper's Ferry disaster in September, 1862, and he well understood

the value of training. In that operation many of the Union regiments

were so poorly trained that they were of little value when the shooting

started. Stannard performed his job thoroughly, earning the respect and

awe of his men. Although Stannard's brigade were among the

least-experienced commands in the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg,

they certainly ranked among the most well-prepared, a point they would

soon drive home to friend and foe alike.

THE LEADERS

While training, discipline and experience were

crucial to success on the battlefield, the quality of the men who led

the rank and file was of equal importance. "Troops without confidence

in their leaders are worth nothing," observed Major Fred Winkler, of

the Eleventh Corps, in a statement that had universal application.

Fortunately, for the soldiers of the First and Second

Corps on Cemetery Ridge, they enjoyed good leadership, and in some

cases, outstanding leadership, from the regimental level on up. The

commander of the Cemetery Ridge line, Major General Winfield Scott

Hancock, ranked as one of the great combat commanders who ever served

with the Army of the Potomac. His division commanders, Gibbon, Hays, and

Doubleday (because Doubleday's division fell within Hancock's line, it

was subject to his orders), were West Point graduates and had plenty of

battle experience. As a brigade commander, Gibbon had trained and molded

one of the finest fighting formations in the army, the Iron Brigade. He

understood the volunteer fighting man, and how to get the most from him.

He earned division command after Antietam. His star was still rising and

he would ultimately rise to corps command. [29]

Doubleday was a competent but uninspiring officer who

possessed a knack for irritating people. He had commanded a division at

Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. On July 1, at

Gettysburg, he performed superbly in temporary command of the First

Corps, but Meade had little confidence in him, and replaced him that

night with Major General John Newton, a Sixth Corps officer. Doubleday

was left simmering in anger over what he rightly considered unfair and

unjust treatment. Still, he was a professional, and Hancock could count

upon him to do his duty. [30]

Alexander Hays had commanded the 3rd Division, Second

Corps, for only three days when the battle began. He led the 63rd

Pennsylvania Infantry earlier in the war, during the Peninsula and

Second Manassas campaigns. An officer of the 20th Massachusetts

described him as "a miserable rowdy," but no one who knew Hays

doubted his personal bravery, or ability to lead and inspire volunteers.

He received his brigadier's star when he was appointed to command the

disgruntled "Harper's Ferry Cowards" fresh from Camp Douglas. Hays

restored the men's ruined morale and whipped them back into a combat

ready unit that one veteran recorded would have followed him "to the

death." When his brigade was attached to Hancock's 3rd Division, by

virtue of seniority, Hays assumed command of the division. If anyone

questioned his ability to lead a division, they were laid to rest on

July 2. One of his men summed up the view of the fighting men toward

Hays's, writing, "I think he is the bravest division general I ever

saw in the saddle." [31]

Of the eight men commanding brigades on Cemetery

Ridge, only two were West Pointers, Webb and Hall. For the 28-year old

Webb, Gettysburg was his first experience commanding infantry. His

previous service had been in the artillery and as a staff officer with

the Fifth Corps. But it was by commanding infantry that rank was gained

in the Civil War, and Webb's assignment to brigade command earned him

his brigadier's star. Despite his inexperience commanding infantry, Webb

understood the principles of leadership. His philosophy was simple, he

would order no man "to go where I would not go myself." [32]

Twenty-six year old Norman Hall had graduated from

the Military Academy in the class of 1858. He had the distinction, along

with Abner Doubleday, of having served in the garrison at Fort Sumter at

the outbreak of the war. Following the Peninsula Campaign, Hall sought

promotion in the volunteers. Apparently his connections were not as

powerful as Webb's. He managed only to secure a commission as a

volunteer colonel, commanding the 7th Michigan Infantry, which he led

through the bloodbath in the West Woods at Antietam. When the brigade

commander was wounded in that battle, Hall assumed command, and

subsequently led it at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. He did well,

but for reasons unexplained, did not win his star. Major Henry Abbott,

of the brigade's 20th Massachusetts, wrote that Hall was "the kindest

superior, as well as the greatest and ablest we have ever had." But

Hall was not a well man at Gettysburg. Abbott believed he suffered from

consumption. "After the battle was over he was so much exhausted that

he couldn't stand up," he wrote to his mother. [33]

The commander of Gibbon's 1st Brigade, William

Harrow, did not stand in the same company as Webb and Hall. Harrow had

been a lawyer before the war and gained the acquaintance of Abraham

Lincoln in this line of work. When the war broke out, he recruited a

company and received a captain's commission in the 14th Indiana. Within

a year he had risen to colonel - a testament to his political

connections. His politics were extreme, residing in the Radical

Republican camp, a point that likely won him few friends among the

professional soldiers around him, nearly all of whom were conservative

Democrats. In April, 1863, he won promotion to brigadier general.

Although he had seen his fair share of combat with the 14th Indiana

there was nothing to suggest he deserved the promotion - certainly he

did not deserve it more than Colonel Hall. The star on his shoulder

straps smelled of politics, a fact apparently well-known in Gibbon's

division. Major Abbott referred to him as "an administration

tool...promoted for a bloodless skirmish out west ostensibly, but really

for cursing rebels." Webb considered him worthless. "He is an ass

and no one respects him," he wrote his wife after the battle. The

fighting on July 2 earned him few admirers in the enlisted ranks. Roland

Bowen, of the 15th Massachusetts, quipped sarcastically: "This brave

man I never saw after the fight first commenced." Fortunately for

Gibbon, Harrow's brigade contained some of the most experienced troops

in the army, and good regimental commanders who would compensate for his

inefficiency.

Hays' two brigade commanders were both pre-war

civilians. Colonel Thomas A. Smyth had emigrated from Ireland in 1854

and settled in Philadelphia, where he earned a living as a carver. He

was something of an adventurer, for he departed in 1855 to take part in

William Walkers's disastrous filibustering expedition in Nicaragua. He

survived this debacle and returned to the United States, where he began

a new career as a coachmaker in Delaware. At the outbreak of the war,

Smyth's prior military experience earned him a commission as major in

the 1st Delaware Infantry. In soldiering Smyth found his niche, and by

February, 1863, he had won promotion to colonel of the regiment. He

accomplished this on ability for he had no political influence or

connections. He assumed command of the 2nd Brigade following

Chancellorsville as the senior colonel. [35]

Seniority had likewise placed Colonel Eliakim

Sherrill in command of the 3rd Brigade of Hays' Division, following the

death of its commander, Colonel George L. Willard, on the evening of

July 2. The 50-year old Sherrill was described as "a man of education

and refinement." He hailed from Ulster County, New York, where he

enjoyed success in the tannery business. His success brought him

prominence and election to Congress in 1847, and to the state senate in

1854. He moved to Geneva, New York, in 1860 where he was regarded as one

of its "most prosperous and influential citizens." During

Lincoln's call for 300,000 volunteers in the summer of 1862, Sherrill

helped raise the 126th New York Infantry, and was rewarded with a

commission as its colonel. He made no pretense as to his military

abilities, admitting when his regiment was assigned to the garrison at

Harper's Ferry in September, 1862, "that he knew nothing about

military; that he made no pretensions to military." However, he

compensated for his ignorance with sheer courage, encouraging and

animating his men in the fighting for Maryland Heights during the

September siege and capture, until he took a bullet in the face that

laid him low. He did not return to the regiment until the end of

January, 1863. Apparently, Hays and he worked well together, for he

became "one of General Hays' most esteemed officers." At

Gettysburg, when Willard was killed, through some misunderstanding or

error of judgment on Sherrill's part, he ordered the brigade back to its

old position on Cemetery Ridge from where it had been ordered by

Hancock. That General came thundering up as the brigade marched away and

without inquiring why they were moving promptly placed Sherrill under

arrest. [36]

On the morning of July 3, Colonel Clinton D.

MacDougal, of the 111th New York, in command of the 3rd Brigade while

Sherrill remained in arrest, and General Hays, visited Second Corps

headquarters to plead Sherrill's case to Hancock. The Corps commander

reconsidered his hasty actions of the evening before when the fire of

battle had been upon him, and ordered Sherrill restored to command of

the brigade.

In Doubleday's division, George J. Stannard had seen

limited field service. He served with the 2nd Vermont Infantry, as its

lieutenant colonel, during the early stages of the Peninsula Campaign,

then departed in July, 1862, to gain a colonel's commission and command

of the 9th Vermont Infantry. As related earlier they ended up with the

Union garrison at Harper's Ferry in September 1862. Stannard's able

command of his inexperienced regiment in the siege and capture stood out

sharply, and he earned a promotion to brigadier general in March, 1863,

and command of five ninth-month Vermont regiments in the defenses of

Washington. Despite his lack of a professional background, Stannard

understood soldiering and was a man to be counted upon. His men

respected and feared him. In trying to fix a reason why the raw 9th

Vermont did not break and run as some other regiments did during the

siege and capture of Harper's Ferry, Edward H. Ripley confessed that he

believed it was because "we were as afraid of Stannard, our Colonel,

as of the enemy." He enjoyed Hancock's confidence, for the Second

Corps commander let him alone and made no adjustments to the changes

Stannard made on his front during the morning of the 3rd. [38]

Of Doubleday's two remaining brigades, only the two

regiments from the 1st Brigade posted in the front line, commanded by

Colonel Theodore B. Gates, of the 20th New York State Militia, would be

severely tried on July 3. Gates had commanded his regiment through the

fires of Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and

Chancellorsville. He was an unabashed self-promoter, but he knew his

business. These were the key leaders on the ridge. They were supported

by generally experienced regimental and company officers, and good

fighting men.

SKIRMISHING, SHARPSHOOTERS, SUN AND SLEEP

These four words characterized the morning of July 3

for the defenders of Cemetery Ridge. At first light - before 4 a.m. -

firing broke out between the skirmish lines near the Bliss farm, the

combatants taking up where they left off the evening before. Except for

those soldiers under fire or firing, most paid no attention to it.

"At the commencement of the war such firing would have awakened the

whole army," wrote Lieutenant Haskall; "not so now. The men upon

the crest lay snoring in their blankets, even though some of the enemy's

bullets dropped among them." As for the rest of the Cemetery Ridge

front, Haskall recorded "no enemy, not even his outposts, could be

discovered along all the position where he so thronged upon the Third

Coeps yesterday." James Wright, of the 1st Minnesota, concurred with

Haskall. "Very little could be seen of the enemy on our front,"

he wrote, "though it was certain they were there yet." [39]

This sparring on the skirmish line rapidly spread

across the entire front of the line. Colonel Veazey wrote that at 3:45

a.m. the Confederates sent a line of skirmishers down against his line,

"and the skirmishing continued more or less all the forenoon."

The action on the skirmish line rose and fell like a symphony throughout

the morning. The Bliss farm was a particularly hot spot. Occasionally,

artillery from both sides entered the fray. At 8 a.m., A. P. Hill's guns

began shelling the northern end of the line, dropping shells in on

Woodruff, Arnold and Cushing. The Second Corps gunners largely suffered

through it with a stiff upper lip, although from time to time they were

permitted to return the fire. The Confederates enjoyed some success. One

shell blew up three limber chests in Cushing's battery, although

miraculously no men were killed, and another exploded a limber in

Woodruff's Battery. There were many close calls. Lieutenant Theron E.

Parsons, of the 108th New York, lying in support of Woodruff, recorded

in his diary that morning that "the shells have struck all around

us," but there were no casualties. According to Captain Hazard,

before the noon lull settled over the field, Woodruff's Battery had

eight separate engagements with Southern guns. Sergeant Frederick Fuger,

in Cushing's Battery, recorded that they had three or four engagements,

"lasting a few minutes each time; no casualties." [40]

There were plenty of casualties on the skirmish line.

Lieutenant George L. Yost, of the 126th New York, offered some idea of

this deadly service, when he wrote his father: "I would do anything

rather than skirmish with those fellows [Confederates]. I never want to

do it again. I will repel charges but don't put me in that place

again." [41]

Sharpshooters plagued nearly everyone on Cemetery

Ridge. "Our lines were continuously menaced by sharp shooters, and we

moved but little in an upright position unless required" recalled

Ralph Sturtevant, of the 13th Vermont. These unpleasant fellows

concealed themselves "behind stones and fences and buildings and in

tree tops," and fired at anyone who exposed themselves. Francis

Galwey, of the 8th Ohio, wrote that on his regiment's front the

"firing was rapid enough, and yet there was not much random work. It

was almost as much as a man's life was worth to rise to his height from

the ground." Staff officers, artillerymen, and officers were

favorite targets, for they had to expose themselves as they went about

their duties. [42]

The infantrymen lay low, concealed behind their

works. Some, despite the dangers about them, fell fast asleep. Sergeant

Wright, of the 1st Minnesota, recalled that he and his comrades did so,

after working to construct a breastwork to protect themselves. "It

seems strange now that we could have done this, for at irregular

intervals shells shrieked over us, or we heard the thud of a bullet in

the ground," he wrote. But extreme fatigue will reduce a soldier's

fear of danger. Galwey related that this was the case in his regiment.

Although they were on the skirmish line and exposed to constant firing

and shelling, he recalled that, "so exhausted had some of our men

become that they slept through a good part of the forenoon." [43]

As the morning wore away the sun became another enemy

to be cursed. The men had cheered its appearance in the morning, but as

it rose in the sky it gave off a heat that Anthony McDermott described

as "almost stifling." The air hung heavy and unmoving. "Not a

breath of air came to cause the slightest quiver to the most delicate

leaf or blade of grass," wrote McDermott. Many combated the sun's

fierce rays by rigging up their rubber blankets, canvas side up. Those

without shelter suffered. Stannard's men apparently lacked the mean's

with which to shelter themselves, and one Vermonter wrote that the sun

"beat down upon us with such force that it was almost

unbearable." [44]

By 11 a.m. a stillness settled upon the field, as if

the heat had sapped the combatants of their energy. The Bliss farm had

been set afire by order of Alexander Hays, which removed the most

contentious point on the Cemetery Ridge front. "Almost absolute quiet

prevailed along the lines," wrote Stannard's aide, Lieutenant

Benedict. Over 20 years later, Anthony McDermott remembered it vividly.

"Of that stillness you have often heard," he wrote; "no

language of mine could cause you to imagine its reality, such a

stillness I had never experienced before, nor since, and I have borne

part in every engagement of the Army of the Potomac." [45]

CANNONADE

Few men on Cemetery Ridge could agree on the time the

signal shots were fired from the Confederate line to commence the

bombardment of the Union position. Lieutenant Benedict was quite

specific, writing, "At ten minutes past one o'clock the signal gun

was fired." But Francis Galwey was equally emphatic as to the time.

"At ten minutes to one precisely, by my watch," he recalled, the

enemy fired their signal guns. Ralph Sturtevant, of Stannard's brigade,

perhaps unintentionally, highlighted the vagaries of time on a

battlefield when he wrote that "the consensus of opinion as to the

time the signal guns were fired and the battle opened in the afternoon

of the last day is between one and two o'clock." It depended upon

the watch of the wearer as to the time the bombardment began. [46]

There was nearly universal agreement among the

defenders that the Confederates fired two signal shots to open the

bombardment. Evidence indicates that both shells struck near the 19th

Massachusetts in the reserve line. Sergeant John W. Plummer, of Company

D, 1st Minnesota, wrote to his brother after the battle, that he and

some comrades had gathered around a lieutenant of the regiment, who had

somehow obtained a copy of the July 2 edition of the Baltimore Clipper.

While the men listened to the lieutenant read, Plummer wrote that a

Confederate cannon fired and its shell struck about "twenty yards

from us." Captain John Reynolds, of the 19th Massachusetts, stated

that this same shell was a solid shot, and that it "came bounding

over the ridge like a rubber ball." A second shot followed the first

from the same direction. Reynolds recalled that Lieutenant Sherman S.

Robinson, of Company A, leaped to his feet after the first shell struck

nearby. The second shell, which apparently was also a solid shot, hit

Robinson in the left side and disemboweled him. If Reynolds' memory

served him right, Sherman S. Robinson was the first man to die in the

great cannonade of July 3. A third shell apparently followed the first

two, and this one passed through some of the gun stacks and shelters of

the 19th. Moments after this third shell arrived on Cemetery Ridge, the

Confederate front exploded in fire, as 140 to 150 pieces of artillery

opened the pre-assault bombardment of Cemetery Ridge. [47]

"Such an artillery fire has never been witnessed

in this war," wrote Sergeant Plummer. "It makes my Blood Tingle

in my veins now; to think of" recalled Ben Hirst, of the 14th

Connecticut, "Never before did I hear such a roar of Artilery, it

seemed as if all the Demons in Hell were let loose, and were Howling

through the Air." Lee's bombardment had two objectives. First, to

smash up the Federal artillery and inflict losses and confusion in the

infantry line. Second, to demoralize the defender and break down his

will to defend Cemetery Ridge against the impending infantry attack. [48]

The Confederate shells poured down upon the Union

defenders with a rapidity that struck fear into even the most

hard-bitten soldier. If the Confederate artillerymen averaged one shot

per minute from each of their guns - a reasonable estimate given the

rapid nature of their fire - and 140 guns were firing, then every second

two or more shells were bursting over or striking the Union line. "It

was one grand raging clashing of sound," wrote Captain Reynolds, of

the 19th Massachusetts, with the "bursting of shells so incessant

that the ear could not distinguish the individual explosions." The

infantrymen hugged the earth for dear life; "we would have liked to

get into it if we could," said Joseph McKeever, of the 69th

Pennsylvania. Sergeant George H. Scott, in the 13th Vermont, wrote that

the men "get behind trees, stones, knolls, stone walls, breastworks,

- anything to give them a partial protection...to walk along the ridge

is madness." [49]

The artillerymen of Hazard's Artillery Brigade were

not as fortunate as the infantrymen. When the Confederate artillery

opened fire, the gunners sprang to their posts and the drivers mounted

the horses on the limbers and caissons, all of them terribly exposed to

exploding shells and shrapnel. Until they received orders to return

fire, they simply stood the enemy fire - an act that required

unimaginable courage. According to John H. Rhodes, of Battery B, 1st

Rhode Island, orders to return fire were not forthcoming until ten or

fifteen minutes after the firing began. This seems excessive and perhaps

it only seemed that long to Rhodes. Eventually, battery commanders

received orders to return fire and the men jumped to their work,

relieved to be able to focus upon something besides being torn to pieces

by a shell. [50]

Gradually the Union batteries from Little Round Top

to Cemetery Hill began to fire, most of them firing slowly and

deliberately, adding their deep bass roar to the already deafening

noise. Dense clouds of smoke, trapped by the hot, humid air, enveloped

the Union gunners, until, recalled Christopher Smith in Cushing's

battery, "the smoke became so dense that we could not see nothing on

the other side of the valley."

General Gibbon wrote that, "over all hung a heavy

pall of smoke underneath which could be seen the rapidly moving legs of

the men as they rushed to and fro between the pieces, carrying forward

the ammunition." Eventually, the smoke became dense enough that in

Cushing's Battery, and others of the Second Corps artillery brigade,

targets were no longer visible and the gun crews simply set the gun to

what they believed was the proper elevation and blazed away. As

the bombardment continued, the effectiveness of both armies' artillery

decreased. [51]

The ineffectiveness of the Confederate artillery was

relative, contingent upon where one was or what one was doing. To the

Union gunners of Hazard's Artillery Brigade, the fire was murderous.

"It was terrible beyond description," Albert Straight, of Battery

B, 1st Rhode Island, stated. Colonel R. Penn Smith, of the 71st

Pennsylvania, whose right wing lay quite close to both Cushing's and

Arnold's batteries, wrote, "My God it was terrible...The field was a

grave." At one point, almost simultaneously, shells burst over open

limber boxes in Cushing's battery. Lieutenant Haskall, who witnessed

this event, wrote, "in both the boxes blew up with an explosion that

shook the ground, throwing fire and splinters and shells far into the

air and all around, and destroying several men." Haskall probably

used the word "destroying" rather than "killing," deliberately, to

describe the effect of the explosion upon the bodies of the unfortunate

gunners caught within its blast.

Civil War shell fragments and shrapnel often

inflicted frightening wounds. One shell, which burst at the muzzle of

one of Lieutenant Perrin's Napoleons, offers a grim illustration of

this. Alfred Gardner and William Jones were preparing to ram a fresh

shell down the tube of their piece, when a Confederate shell struck

their gun and burst in their faces. A fragment of the shell hit Jones in

the head, cutting the top completely off. Gardner took a fragment in the

left shoulder, nearly severing his arm. He died shouting, "Glory to

God! I am happy! Hallelujah!" In Arnold's battery, John Zimla, while

acting as a gunner, had his head shot off by a shell. Another man in the

same battery had his arm and shoulder torn off. The frightful nature of

these wounds is what made artillery fire so demoralizing to those on the

receiving end. The decapitation of one man could demoralize an entire

gun crew, or section, or battery, under the right circumstances. [53]

The destruction and loss the Confederate artillery

inflicted upon Hazard's batteries is reflected in the severe losses they

suffered. Arnold's battery lost 4 killed and 28 wounded, about

one-quarter of its strength.

|

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

In Cushing's battery, 83 horses were killed, 7

enlisted men were killed and 38 wounded. Woodruff lost 40 of 60 horses,

and 25 officers and men. According to the historian of the 19th

Massachusetts, in one-half hour Rorty's battery had only one gun still

in action and only one officer, Rorty, and 4 men, out of 60. While 20 or

30 men in an infantry regiment might have been regarded as moderate or

light losses, they represented nearly 25 to 30 percent of a battery's

strength - losses that could, and often did, cripple it. To maintain a

rate of fire in some of the batteries it became necessary to call upon

infantry volunteers to serve the guns. Colonel Smith, of the 71st

Pennsylvania, detailed 15 of his men to help serve Cushing's guns, and

20 men of the 19th Massachusetts pitched in with Rortys battery. [54]

The front-line infantry, proportionally, did not

suffer as severely as did Hazard's batteries, but they took their share

of casualties, depending upon where a unit happened to be in line. The

1st Minnesota, for instance, reported no losses, and the 20th

Massachusetts had very few. Others were not so fortunate. The rail

breastworks thrown up to protect the 20th New York State Militia and

151st Pennsylvania were struck by numerous shells which sent the rails

flying with great force, injuring or killing anyone they struck. One

shell struck the breastwork of the 59th New York, passing completely

through it, killing 1 and wounding 6 men. Webb wrote that his brigade

lost 50 men during the cannonade. Colonel Veazey reported that the 16th

Vermont suffered severely in the bombardment, but not as heavily as the

14th Vermont, who lost 60 men. The 13th Vermont escaped similar

punishment during the bombardment by crawling forward to the breastwork

of rails they had thrown up earlier in the day. The Confederates had the

range of their former position, but not of the forward one they moved

to. [55]

Zeigler's Grove was a particularly unpleasant place

to be posted. "Not a second but a shell-shot or ball flew over

us," wrote Chauncey L. Harris, of the 108th New York: "Large

limbs were torn from the trunks of the oak trees under which we lay and

precipitated down upon our heads." Within five feet of Harris five

shells struck "a large oak tree three fret in diameter," one of

which passed clean through it. Another shell burst at his feet and

killed a sergeant and private. Yet another blew up one of Woodruff's

caissons. At this, several men started toward the rear, but Lieutenant

Dayton T. Card, of Company H, drew his sword and ordered them back. They

obeyed, but moments later a piece of shell struck Card in the breast and

killed him. Carelessness of Woodruff's gunners subsequently led to even

bloodier consequences in the 108th's ranks. To save time the gunners had

stacked shells near their guns - close to the 108th. A lucky, or

unlucky, Confederate shell struck in them and blew up the lot. "It

was an appalling sight and to this day is a horrible one to think off

[sic]," recalled Captain David Shields, an aide-de-camp of General

Hays. This event shook the entire regiment. Somehow (he does not relate

what means he employed) Shields managed to restore confidence in the

regiment. [56]

The mental strain of the bombardment was intense.

Sergeant Wright, in the 1st Minnesota, wrote that "we had been badly

scared many times before this but never quite so badly as then," a

statement that deserves notice considering the service this regiment had

seen. In the 14th Connecticut, Ben Hirst recorded, "how we did hug

the ground expecting every moment was to be our last. And as first one

of us got Hit and then another to hear their cries was Awful. And still

you dare not move either hand or foot, to do so was Death."

For the duration of the nearly two hour long

shelling, Anthony McDermott, in the 69th Pennsylvania, recalled, "we

did not enjoy any space of relief from the dread of being ploughed into

shreds." Some men were stricken with fear and sought safety in

flight. Most hugged the earth, not necessarily out of courage, but

because it was safer than making a run for it across the shell-swept

rear. As Captain Cook observed, "a retreat would have to be made

under the guns of the enemy and almost as dangerous as to remain where

we were." It what might be imagined to be the most unusual reaction

to the shelling, many men fell asleep! "The effect of this

cannonading on my men was the most remarkable I ever witnessed in any

battle," wrote Colonel Veazey; "many of them, I think the

majority, fell asleep." Francis Galwey recalled a similar reaction

in the 8th Ohio. He believed it was the monotonous roar of the guns that

caused him and many others to nod off. [57]

Many soldiers found courage from the example of their

leaders. Hancock stood out conspicuously. He rode the line under fire

accompanied by his personal standard bearer in a sublime example of

leadership. When an officer remonstrated against his exposure, Hancock

allegedly replied, "there are times when a corps commander's life

does not count." Gibbon discovered that "most of the shells burst

high and behind us," so that it was actually safer the farther

forward one went. He took his aide, Lieutenant Haskall, and crossed the

works in the area occupied by the 69th Pennsylvania, to see if they

might catch a view of an enemy advance. Along the way they encountered

Alexander Webb, "seated on the ground as coolly as though he had not

interest in the scene." Gibbon's walk had the unforeseen consequence

of giving courage to the infantrymen huddled behind the wall. He

recalled them "peering at us curiously" as they walked the line.

At one point they came upon several soldiers who had left the ranks to

find shelter in a nearby excavation. Haskall recalled that Gibbon said

in a fatherly fashion to the men; "My men, do not leave your ranks to

try to get shelter here. All these matters are in the hand of God, and

nothing that you can do will make you safer in one place than

another." Gibbon's logic did the trick and the men returned to their

regiment. Ralph Sturtevant observed that General Stannard "apparently

paid no attention to exploding shell or whizz of bullet," and went

about his duty with a calm courage that gave strength to his men.

Alexander Hays, too, stood out prominently, recklessly exposing himself

to cheer and encourage his men. Despite the outward appearance of

fearlessness, all of these officers harbored fears. "None but fools,

I think, can deny that they are afraid in battle," wrote Gibbon. Yet

somehow they found the means by which they conquered their fears and

were able to perform their duty. [58]

There were many leaders of lesser rank whose bravery

gave their men strength and the courage to hold on. Lieutenant Card

comes to mind as one example. Lieutenant Rorty was another. When so many

men of his battery had become casualties, he tossed off his jacket, took

up a rammer and helped crew the one piece still serviceable.

In Cushing's battery when a solid shot destroyed the

wheel on the number 3 piece, the sergeant in command of the gun and his

crew were panic-stricken and started to run. This was the effect the

Confederates sought by their bombardment, to break the morale of the

Federal soldiers. But Lieutenant Cushing was equal to the moment. A

baby-faced, slender man, Cushing did not fit the popular image of a

hero. However, Christopher Smith recalled him as "the bravest man I

ever knew." Cushing drew his revolver and ordered the sergeant back

to his gun. Then he called out to his Battery, "the first man who

leaves his post again I'll blow his brains out." Apparently, his men

took the threat to heart. In several minutes the wheel on number 3 had

been repaired, and the gun was blazing away again. [59]

Not all leaders provided a positive example for their

men. Captain David Shields, Hays' aide-de-camp, while riding back to

Meade's headquarters to deliver a message during the bombardment,

noticed Lieutenant Colonel Levi Crandall, commanding the 126th New York,

sitting in rear of Cemetery Ridge holding his horse, not with his

regiment. On his return Shields saw that Crandall had not stirred and he

rode up to him "and was very indignant" that the colonel was not

with his regiment. Crandall complained that he was sick. Shields ordered

him to his regiment, but Crandall refused to budge. "I left him

sitting on the ground a miserable man, sacrificing all, for what he

thought was the safety of his wretched body," recalled Shields.

Fortunately, the Cushing's, Shields', Card's, and their like, greatly

outnumbered the Crandall's on Cemetery Ridge, and gave the fighting men

the leadership they needed to ride out the bombardment and meet the

storm-wave that would follow. [60]

THE ADVANCE

By 3 p.m. the bombardment had run its course. The

Confederate guns had largely exhausted their ammunition, and the Union

guns, except Hazard's brigade, had ceased fire earlier under orders to

conserve ammunition for the anticipated infantry attack. Hancock had

countermanded orders issued by artillery chief, Brigadier General Henry

Hunt, for Hazard to cease fire, and ordered the batteries to re-open.

This exhausted the long-range ammunition of Hazard's batteries, but they

were all so badly shot up that even had they followed the course Hunt

advocated it may not have made an appreciable difference.

Nearly one-half the officers and men of the brigade

had been killed or wounded. Rorty's battery had one, perhaps two,

serviceable guns. Battery B, 1st Rhode Island, was a wreckage. Its

officers were all dead or wounded and there were not enough men to serve

the guns that were left. Cushing could man only two guns. Arnold's

battery remained intact, but its long-range ammunition was gone.

Woodruff's battery was in similar straits.

Of 24 guns in Hazard's brigade that were present at

the commencement of the bombardment, only 11 or 12 were still in service

when it ended, and these had only canister left. For the Union infantry,

who were accustomed to the superiority of their artillery, it was a new,

and rather unsettling state of affairs. "For the first time in our

experience, they [the Union batteries] were powerless to silence the

rebs," wrote Sergeant Plummer, of the 1st Minnesota.

Losses in the infantry ranks cannot be determined

with any degree of accuracy. A reasonable guess would place their losses

at 200 to 300 men, but they may have been higher. But 300 men were equal

to a strong regiment on the firing line, at a time when every rifle and

musket would be needed.

The brief lull that followed the cannonade gave

little time to repair the damage done by the Confederate artillery. The

overshots by the Southern guns had made the movement of ammunition or

troops in rear of the Union center far too dangerous. Fresh batteries

from the army reserve, ammunition, and troops were ordered toward the