|

"A LABORIOUS AND VEXATIOUS TASK"

The Medical Department of the Army of the Potomac from the Seven Days through the Gettysburg Campaign

Gregory A. Coco

"[The] battlefield sucks everything into its red

vortex for the conflict, so does it drive everything off in long,

divergent rays, after the fierce centripedal forces have met and

neutralized each other."

Oliver Wendell Holmes

For the medical department of the Army of the

Potomac, the Battle of Gettysburg may have been its most difficult test.

Whether or not it succeeded in that supreme moment will become clearer

as these pages unfold. First, however, it would not be out of place to

examine the important series of events which metamorphosed that

department prior to its climatic appointment in Pennsylvania.

From the very beginning of human civilization armies

have emerged to protect and uphold a nation's citizens' wealth and

territory. And in consequence thereof came the uncivilizing hand of war.

Combat, as well as the large concentrations of encamped soldiers

inherent in military campaigns, resulted in wounds, injuries, and

disease, all of which had to be dealt with for the physical and

emotional well-being of the forces involved. Although some small

advances had been made throughout the centuries, military medicine,

hospitalization, and the evacuation of the sick and wounded had, for its

worth, remained of little import within the overall scheme of an army's

organization, duties, and responsibilities.

By 1860 the United States had itself, barely moved

beyond the concept that "a collection of armed men constitutes an army,"

and similarly from the idea that civil practitioners were, if attached

to that body, competent enough to act as the "medical department." So by

1861, and the outbreak of hostilities between Northern and Southern

states, the prevailing medical philosophy basically remained a task of

the individual, or, every man for himself. In the U.S. Army,

unfortunately, there was regimental aid, and nothing more. But as the

tiny rebellion escalated, and 36,000,000 people became involved, these

old-fashioned ideas and methods were destined to be altered. That

inevitable adaptation though, came slowly and in spurts. Awkward and

haphazard at first, it was also forced to crawl over the self-righteous

protests of narrow-minded civilian and military bureaucrats. Revision

did come because of a natural necessity, and due to the uncounted and

horrible experiences of the men-at-arms who endured the backwardness of

the old system.

"The volunteer soldier offers his very dearest

possession to his country, his blood his limbs, possibly his life. When

the soldier is struck down shall his country leave him on the field

suffering from cold, pain, thirst, even hunger; to die perhaps, without

aid, unless he can drag himself away by his own painful exertions?

Certainly when he gives his dearest possession the country should not be

niggardly, when all it can give is dollars, but should supply an

abundance of the best possible means for his succor." [2]

The physician who is quoted above believed that the

value of preparedness surpassed all other virtues of an army or its

medical branch. It was akin, he said to that of a fire department to a

city. "It must always be prepared for its main function, and must be

prepared to respond instantly,..." [3]

This preparedness did not exist in the U.S. Army and

particularly in the Army of the Potomac in 1861 and much of 1862 for two

major reasons. First, the enormous growth of the war and its resulting

waterfall of casualties caught even the most ardent realists by

surprise; and secondly, the normal organization of the medical

machine did not lend itself to quick changes or to the adoption of new

ideas, theories, or techniques. Therefore, it ensured the lack of a

centralized and autonomous system for the evacuation of wounded, the

establishment of field hospitals i.e., "movable hospitals", and the

supplying of medicines, equipment, and provisions, which then became the

main ingredients for disaster in the wake of Civil War battles, great

and small. It took three years before the medical department was truly

capable of satisfactory conduct in transporting and caring for its hurt

and diseased personnel.

Excepting the usual minor and expected complications

encountered in the early battles and skirmishes, it still required the

frightful Peninsular Campaign and its aftermath in the spring and summer

of 1862 to fully thrust into the limelight the helplessness and disarray

of the U.S. Medical Department, as it coped with the casualties of a

growing modern war. A dozen or more engagements, fought by two huge

armies in a markedly unhealthy region of Virginia, complimented by

numerous long and stifling marches and retreats, produced a never before

convergence of sick and bleeding Americans. Added to these bleak

conditions was the lack of fresh water, and the predominance in the

ranks of green untested volunteers fresh from home. Well over 21,000

wounded alone in the Peninsula fighting, told some of the ghastly tale;

the shock to the Northern populace can surely be imagined, especially

when combined with the news of 8,500 additional injured at Shiloh,

Tennessee, during the same period. [4] And since

victims of disease far outranked the numbers of dead and wounded during

that timeframe, one may clearly understand the sheer magnitude,

unexpectedness and incredulity of these figures.

It was during this particular timeframe that several

significant transitions occurred in the Eastern army. Although not

always permanent features they foreshadowed some promise for the future.

Soon after the Battle of Bull Run in late July 1861, Dr. Charles S.

Tripler succeeded Surgeon William S. King as medical director of the

Army of the Potomac. During King's term his position was frequently

without instruction as to its duties, privileges and powers, and King,

being attached to the commanding general's personal staff, had only such

control as his personal influence might win for him. "He was the only

possible coordinator of the battlefield relief work,yet was without

authority to organize and direct the medical officers and stretchermen

of the various regiments." [5] Consequently, each

regimental surgeon took responsibility for only his men, leaving all who

fell sick or injured away from his unit, "on their own hook."

Shortly before the onset of Tripler's appointment in

August 1861, the winds of change had begun to blow. These winds had been

assisted and even tactfully nurtured by the newly created United States

Sanitary Commission (U.S.S.C.), the brainchild of Reverend Henry W.

Bellows and Dr. Elisha Harris, both of New York. Concerned that the

sanitation and supply efforts to the armies of the Union were wholly

inadequate for the good of the troops, this private relief agency had

been organized, and had quickly grown. Although the commission's central

desire was quite modest, that of collecting and supplying articles

useful to the sick and wounded, it shortly found itself beset with

roadblocks. However modest as its aims were, initially the U.S.S.C. was

seen by the army's medical officiary in Washington as not only

impertinent and a nuisance, but plainly civilian interference.

Fortunately for the men in the field, as Dr. Tripler commenced his

duties, improvements launched by the Commission, (as its prominence

grew) and more strict adherence to existing army regulations, begun to

make a noticeable difference in the health and morale of the troops. [6]

Under General George B. McClellan, Tripler, who was

not regarded as an innovator but merely a fine administrator, did seize

the opportunity to institute some long overdue and much needed reforms.

Although constantly stymied by Surgeon General Clement A. Finley, he

still managed to improve evacuation methods, he outlined a clearer

declaration of surgeons' duties, insured better training of hospital

attendants, added more disease prevention, and established auxiliary

general hospitals in Washington and elsewhere. Many of his other ideas

were never implemented due to the indifferent disposition of the

department, the large influx of new enlistments, and other factors

beyond his control.

In April, 1862 a major blockage to progress was

broken up in Washington which would in many ways forever transform the

medical department of the U.S. Army. Surgeon General Finley, described

by one detractor as a "self-satisfied, supercilious, bigoted

blockhead... [who] knows nothing and does nothing..." was removed

from office through the efforts of the Sanitary Commission, major

newspapers, and other forward-looking thinkers. The Medical Corps under

Finley, said the New York Tribune, "is not accused of misifeasance or

malfeasance, but of non-feasance, [and has] done nothing since the war

began." [7] As a result, the complicated and long

campaign for his replacement eventually netted Dr. William A. Hammond, a

distinguished surgeon and scientist, who was a friend of McClellan's,

and even as an unknown entity was totally supported by the U.S. Sanitary

Commission. But in choosing Hammond they passed over men with seniority,

one in particular was Assistant Surgeon General R.C. Wood, who claimed

he had been promised the position. In the end these "seniors" would have

their revenge.

Dr. Hammond, at 34, could not have been a better

choice. With eleven years of frontier service, he was still open-minded

with a keen inquiring intelligence. These were weighty attributes, but

his eager willingness to tackle the serious problems within the army's

medical system was his chief merit. Regrettably for the country, and

especially its citizen soldiers, he was eventually forced out of office

by the petty and vindictive Dr. Wood and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

In the meantime, however, he formulated and implemented desperately

needed priorities for the remodeling of his bureau. Some William Hammond

of these immediate measures insured that expenditures for supplies went

up, "red tape" was cut, supplemental nurses and physicians could be

employed when needed, and a new ambulance organization was instituted.

Further on, he drafted designs to add extra surgeons to regiments and

staff, along with a new complement of medical inspectors for the field

armies and general hospitals. He authored the concept of an Army Medical

Museum and medical school, and sought pay increases and higher ranks for

his dedicated officers. Three of his most beneficial advances involved:

the removal of the transportation of medical supplies and patients away

from the Quartermaster's Department and into the jurisdiction of the

Medical Corps, the betterment and expansion of the general hospitals,

and the replacement of medical directors with younger men who showed

administrative ability, and were "not quite so thickly encrusted with

the habits, forms and traditions of the service." [8]

One of the men chosen by Surgeon General Hammond to

implement this transformation of the antiquated medical corps was

Jonathan Letterman, MD, a 37-year-old Pennsylvanian and 1849 graduate of

Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. Letterman had entered the

army upon receipt of his diploma, and had served in Florida against the

Seminoles, and subsequently spent almost five years on the frontier. In

the two years prior to the Civil War he was stationed at Ft. Monroe,

Virginia and participated in an expedition against Indians in

California. Returning to the East in November 1861 he took up the

position of Medical Director of the Department of West Virginia. On June

19, 1862 Dr. Letterman was ordered to duty as Medical Director of the

Army of the Potomac, succeeding Charles Tripler. He reported to General

McClellan at White House Landing on the Virginia Peninsula, July 1. Upon

receipt of the news of Letterman's orders, a nurse at the Landing named

Katharine Wormely wrote in a letter home: "A new Medical Director of

the army has been appointed, for which we are deeply thankful. He...has

just stood near me for a few moments,...so that I could observe him,...

His [face] gave me a sad calmness. Such a worn face, - worn in the cause

of suffering, full, it seemed to me, of a strong earnestness in his

work. How much at this moment is freshly laid upon him!"

Friends described the doctor as a man with a

"truly modest disposition, great kindness of heart and sensibility to

the feelings of others." Surgeon Letterman was also reported to

possess a healthy sense of humor, and a directness of speech and manner,

accompanied by a frank and sincere nature, who was unselfish in his

generous praise of others. General William W. Loring who had served with

Letterman in New Mexico, (and against him in the Civil War) pronounced

him both retiring and gentle, and an ardent student who sought the

"highest knowledge in the scientific advancement of his

profession." [9]

During their tenures as Surgeon General and Medical

Director of the Army of the Potomac both Hammond and Letterman,

respectively, worked diligently and in a partnership to bring about

crucial modifications to a structure overloaded and burdened by every

problem imaginable. In following Letterman's handiwork, in combination

with Hammond's guidance during the twelve months prior to the Gettysburg

Campaign, it is possible to observe his accomplishments and failures,

and to understand whether basic lessons he taught and learned from the

end of the Seven Days' Battles through Chancellorsville did or did not

prepare that army's medical branch for its monumental crisis at

Gettysburg.

When, on July 1, 1862, Jonathan Letterman began his

duties at McClellan's headquarters he was immediately thrust into the

midst of a vast conglomeration of sick and exhausted soldiers who had

endured several months of hot weather, swampy terrain, and the

debilitating effects of long marches and hard fighting. These hardships

were unhappily coupled with a lack of proper diet, bad water, and the

"depression of failure." [10] Surgeon Tripler

had done his best up to Letterman's arrival, but the many negative

components within the medical department, plus the size and scope of the

campaign had done him in. The sick alone were a crushing encumbrance,

numbering at least 20 per cent of the army. In fact over one-fourth of

McClellan's troops were then languishing in crowded hospitals at

Harrison's Landing where the Army of the Potomac had retreated after

Malvern Hill. Letterman immediately went to work, requesting 200 more

ambulances and 1000 additional tents. On August 3 he began the

evacuation of the sick and wounded which continued until August 15.

Finally released from this awesome burden, the army was free to move at

will.

While engaged in this mammoth endeavor, Letterman

still found the spirit and energy to take up the long-standing ambulance

problem and work for its solution. Although the final resolution did not

evolve purely from him, Letterman did devise an innovative and workable

evacuation process and put it quickly into practice. Whereas many

medical officers had learned valuable lessons during the Peninsular

Campaign, (where Letterman had not been present), it was obvious that he

more than anyone had seriously considered the ambulance question and had

already mapped out a simple yet viable formula long before joining

McClellan in July. Letterman, explained the old methods thusly:

"[The ambulances] were under the control both of

Medical Officers and Quartermasters, and, as natural consequence, little

care was exercised over them by either. They could not be depended upon

for efficient service in time of action or upon a march, and were too

often used as if they had been made for the convenience of commanding

officers."

Emphasizing his main point, it was clear that during

a time of need, especially in battle, no officer, medical or otherwise

should have control over the ambulances, as these men had their own

duties and responsibilities to attend to. Logically, he saw other

officers, "appointed for that especial purpose, should have direct

charge of the horses, harness, ambulances, etc., and yet under such

regulations as would enable Medical officers at all times to procure

them with facility when needed for their legitimate purpose." [11]

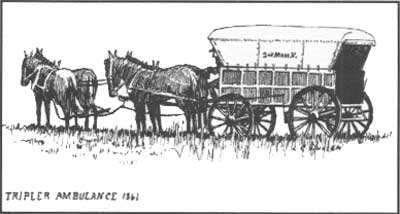

Briefly, the order which was submitted to and

approved by General McClellan on August 2, (instead of being sent to

Washington where it would have reposed indefinitely) provided an

ambulance force for each army corps, commanded by its own

captain. Moreover, each division had a first lieutenant in charge, a

brigade, a second lieutenant, and a sergeant assigned to every regiment.

The enlisted element consisted of two privates and a driver for each

ambulance. This system allowed every infantry regiment one transport

cart and driver, one four-horse and two two-horse ambulances; plus one

two-horse ambulance for each battery of artillery, and two two-horse

ambulances for the headquarters of each army corps. (A two-horse

ambulance was actually a light, four-wheeled vehicle and a four-horse

ambulance was akin to an army wagon.) [12]

Albeit all ambulance corps officers and men came from

the line, they were under the sole control of the medical directors, and

the total number of ambulances allotted depended on the size of the

regiments in each division. For instance three ambulances were permitted

for a regiment of 500 or more. The aggregate was about one vehicle per

150 men. As an illustration, in June 1863, the Fifth Corps contained

12,509 men and had 81 ambulances on hand. More importantly, though,

everything boiled down to this major change: that all ambulances were

taken away from the regiments and were thereafter kept together in a

division train, which was sometimes combined in corps trains and

sometimes not. [13]

Meanwhile away from the field, Surgeon General

Hammond pressed forward his agenda in the nation's capital. He created a

medical inspector general and eight inspectors for the overall

management of military general hospitals and the improvement of sanitary

conditions in army camps. A corps of staff surgeons was added, a total

of 40 surgeons and 120 assistant surgeons to serve outside the

regimental framework. He tightened up the contract surgeon business, and

required strict exams for both entering military and temporary civilian

physicians. Convalescent camps were founded to clear general hospitals

of men caught between the front and the rear of an army, and where many

malingerers had found safe havens from duty. Furthermore, Hammond made

it easier for purveyors to do the job of supplying the department with

medicines, instruments and equipment by expanding their depot locations

and streamlining how requisitions were made, filled, and transported.

All the while he supported his field personnel as they fought for

front-line revisions. In one important move during the Battle of Second

Bull Run (August 29-30), he appointed Surgeon Jeremiah Brinton to the

new post of medical director of transportation, which freed Dr.

Letterman from dealing with that battle's 8,000 casualties then being

moved to the hospitals in Alexandria, and between numerous facilities in

Washington. [14]

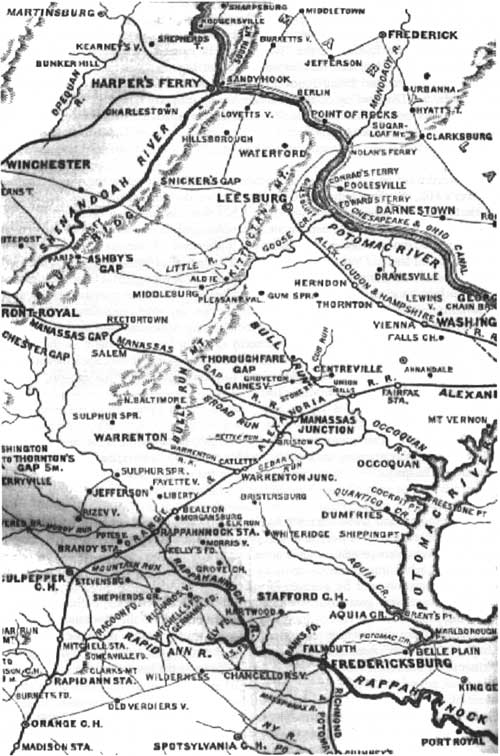

In early September, owing to Robert E. Lee's invasion

of Maryland, General John Pope's Army of Virginia was merged into the

Army of the Potomac, making Dr. Letterman overseer of a much enlarged

force, with his ambulance corps then only one month old. It soon became

an experiment on a grand scale.

By September 18, several engagements had been fought,

including the Battle of Antietam. Although the "Medical Department

had not, at this time, been reorganized...," Letterman still

instructed his corps' medical directors beforehand to form their

hospitals, "as nearly as possible, by divisions, and at such a

distance in the rear of the line of battle as to be secure from the shot

and shell of the enemy..." He further advised the selection of barns

for hospitals (as few tents were on hand due to the rapidity of the

advance from Virginia into Maryland) over houses, as they were

"better ventilated."

In recalling the aftermath of that tremendous battle,

where over 8,300 Federals clung to life after being struck by musketry

and artillery fire, Dr. Letterman disparaged the lack of medical and

surgical stores for these men and the 2,500 Rebels left in his hands,

along with the difficulty of obtaining these items from the depots in

Washington and Baltimore. He understood, however, that the "first

consideration is to supply the troops with ammunition and food - to

these every thing must give way, and became of secondary

importance." [15]

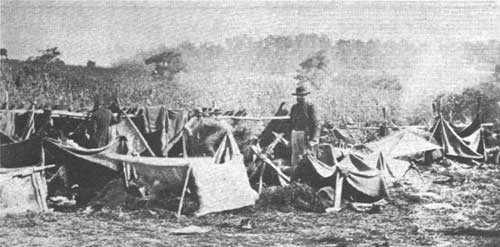

Hospital scene, Antietam, 1862

Prior to the first martial contact of Southern and

Northern troops at South Mountain, Maryland, Letterman called for 12

hospital wagons and two hundred extra ambulances to be delivered to the

army. (Some of the regular ambulances were late in coming, again due to

the fast pace of army movements during the campaign.) Many of these

conveyances did arrive in time, but were unorganized, while some were

lost. Still, Dr. Letterman claimed that the majority of the wounded were

brought off the field in fairly good time, although handfuls of injured

men did lie on contested ground for over 24 hours. Additionally, he gave

his staff of doctors and attendants high marks for their willingness to

work, and their promptness, efficiently and devotion to the casualties

under their care. He also defended his physicians against

misrepresentations and rumors that pictured them as simply butchers,

saying that more often they should have been blamed for practicing

"conservative surgery."

As for the new ambulance system, Antietam did not

become the ground for a model experiment. Critics were vocal in any

event, and bemoaned the evacuation service there as characterized by

"gross mismanagement and inefficiency,...[and a] lack of system and

control." In retrospect some of these faults may have been

attributed to the incorporation of General Pope's untrained drivers and

stretcher-bearers into the Army of the Potomac's better organized and

more disciplined and motivated crews.

Major Letterman had always believed that after a

severe engagement, such as that at Sharpsburg, the critically injured

must not be moved right away, but instead kept immobile nearby until

transportation would not endanger their lives. Therefore he set up two

"large camp hospitals," (besides the main ones in Frederick), or

mini-general hospitals if you will, near the battlefield. These were

capable of maintaining about 1200 patients. He claimed that these

institutions, "were the first of the kind attempted in this country,

and were succesful,...and demonstrated the propriety of their

establishment." [17]

A second prescription adhered to by the director was

the unique concept that allowing relatives to remove seriously wounded

men immediately to their homes was fraught with danger. He felt that not

only was the physical movement bad for the disabled soldier, but

then to be cooped up in stuffy, closed buildings was to compound an

already grievous mistake. Letterman said that the "absolute necessity

of a full and constantly renewal supply of fresh air..." is most

relevant to the health and well-being of the patient. As a result of

these beliefs, he was constantly appealing for the addition and

maintenance of a large number of tents available to the medical wing of

the army.

In examining all of Dr. Letterman's strategies and

methods, it becomes apparent that throughout his tenure as medical

director of the Army of the Potomac, one of his most important causes

was the retainment of wounded men as close to the army as possible. This

would ensure a quick return to their units enabling the successful

prosecution of the war effort. This "directive" had a two-fold benefit,

as it further allowed the men to be close to their own doctors and

comrades which promoted better care and a morale boost in the

process.

As an after-shock of Antietam another significant

problem was attacked by Director Letterman. This was the inception of

"field hospitals," or hospitals-on-wheels, the mobile medical facilities

so common to past and present armies since his day. Up to September

1862, the field hospital concept had not yet been ordained. Regimental

hospitals were the norm, with these enterprises sometimes combined into

the advantage of brigade level cooperatives. Up to that time, the lack

of tentage, and the separation of personnel, supplies and equipment had

made divisional hospitals difficult to formulate and maintain. But after

much study and acquisition of the necessary authority, all this changed.

In a simple and clearly worded circular dated October 30, 1862,

Letterman inaugurated this extraordinary reform. Its main feature was

the direction of a field hospital for each division, and provision of

the personnel and equipment for the same. In addition, a previously

written circular had ordered that from that time on (October 4) supplies

would be issued by brigade to the individual regiments as needed,

eliminating much of the waste and abandonment of these valuable

materials each time regiments moved. The new orders also guaranteed that

every physician and all other attendants knew exactly where they

belonged in the event of a battle, and that only the three most

qualified doctors of a division could be classified as surgical

"operators." [18] The value and superiority of these

revolutionary directives was shortly demonstrated in December 1862 at

the Battle of Fredericksburg, where, as Letterman explained, "they were

first tried, and when from the nature of the action they were severely

tested, they fulfilled in a great degree the expectations hoped for at

the time of their adoption." [19]

In review, and in fairness there is little in the way

of exaggeration contained in the major's preceding statement, as

Fredericksburg presented the medical corps with several serious concerns

and problems. Primarily, the battle was a major defeat for the Army of

the Potomac. Adding to this dilemma was the river, an obstacle which had

to be crossed and recrossed in consequence of the forward establishment

of hospitals, and then the retrograde movement of the same facilities.

And lastly, December was a time of year when severe shifts in weather

could hinder all post-battle activities.

After a long rest period following the Antietam

Campaign, General McClellan began his slow probing maneuvers toward the

Army of Northern Virginia then protecting Richmond in an advance

position near Fredericksburg. So lentitudinous were his movements that

he was relieved by the president, who placed Ambrose E. Burnside in

command. General Burnside sensing Lincoln's mood, hastened the march

over land to capture the Rebel capitol. In preparation of this upcoming

conquest, he transferred the Army of the Potomac to the vicinity of

Fredericksburg in middle November, ignoring the lateness of the season.

His strategy, to take that city as a safe water base enabling a direct

advance to Richmond, was thwarted by the Confederates, who forced

Burnside to attack them across the Rappahannock River where they held

superior, well prepared positions. The one-day battle fought on December

13, resulted in a Union defeat. With 9,600 injured stuck on the wrong

side of a river the situation looked bleak. However in this instance,

"for the first time in a great battle, the wounded of the United

States Army had adequate care and treatment." [20]

Rappahannock River, near Fredericksburg, Virginia

The success achieved by the medical corps after

Fredericksburg was in large part due to the snail-like pace of the

campaign, and the many weeks of preparation available since the Battle

of Antietam. In consequence of the directives instituted by Dr.

Letterman, the medical branch was able to amass supplies such as tents

and ambulances, and train its personnel into the revised theories

implemented in October. For example, 500 spare hospital tents had been

ordered and stored at the depot near Aquia Creek, while for once enough

ambulances were then on hand, about 1000. Several other conditions

enabled the wounded to be speedily and correctly cared for. The weather

remained quite mild for that time of year, as the normal cold

temperatures did not set in until four days after the fighting ended.

Furthermore, the nearby sturdy buildings of the town held by the

Federals provided protection for the injured men and attendants alike.

And curiously, for reasons never clearly understood, the Confederates

did not launch a counterattack against Burnside's defeated army, giving

his doctors the opportunity to stabilize their patients prior to transit

across the Rappahannock. The First Corps medical director, Dr. J.T.

Heard, explained that the prompt and excellent care given to the

casualties was due to a uniformity of action: "Every surgeon,

hospital steward, nurse, cook and attendant was assigned to his position

and knew it." [21]

Since removal of the wounded to the north side of the

river was paramount to their safety from artillery fire, continued

combat, or enemy attack, it was ordered almost immediately. Dr. Heard

reported that his 1,500 cases were not only properly attended to in

three divisional hospitals, but every man was driven or carried across

before morning; and by December 16, all of the nearly 10,000 Union

wounded were sheltered in tents on the northern bank of the river.

Although Letterman protested, evacuation of these men to Washington

began on the same day. As always, he was convinced that to leave

soldiers with severe injuries immobile for awhile, as he had done after

Antietam, was the best policy. But Burnside expected renewed

hostilities, and the evacuation continued unabated. From existing

reports it appears that this relocation of the wounded to the capital

did not go as smoothly as it should have; the biggest problem being the

lack of warm clothing, blankets, and ample rations. In this aspect the

Sanitary Commission lent much aid, but even this organization was hard

pressed to furnish every need. The usual criticisms surfaced and were

directed toward Major Letterman, mainly his unwillingness to delegate

authority and the aforementioned supply problems.

After this battle the Northern army went into winter

encampments at Aquia and Belle Plain, Virginia. And except for

Burnside's last effort to rescue his reputation in the infamous January

four-day "Mud March campaign," all was quiet along the Potomac until the

spring of 1863.

Meanwhile, within the crowded bivouacs the defeated

and heavy hearted Army of the Potomac suffered on. Due to unsanitary

conditions prevalent in the large camps, and the adverse weather,

disease and sickness were by all accounts, rampant. "Letterman does

not appear to quite such advantage as a sanitarian as he does as an

organizer and manager in the field," said one modern historian. A

few of his contemporaries would have agreed. [22] The

loudest disapprovals as usual, seem to have emanated from his enemies in

the government, those doctors who, with Secretary Stanton, were always

busy trying to discredit both Surgeon General Hammond and even Director

Letterman.

The bloody year of 1862 did close, with some good

news, as is noted by these comments:

"It marked the end of an old era, the beginning of

a new one in the medical department of the United States army; the end

of working without authority, the beginning of control; the end of

confusion, the beginning of methods and order."

These changes were surely visible to almost anyone

willing to see. A short eighteen months earlier the entire U.S. Army

contained barely 100 medical officers, and was indifferently supplied

and organized. As 1863 dawned, it was comprised of 2,000 doctors and

nearly 10,000 men under their command or direction, complete with

general hospitals in the large cities containing more than 50,000 beds.

It was compacted, well trained, with an ambulance corps and purveyors

office unsurpassed. And it had just proven that one of its branches,

that of the Army of the Potomac, could reliably handle 10,000 casualties

in a single day. [23]

With the vast improvements in medical service

beginning to become apparent, 1863 should have been a banner year for

Medical Director Hammond and his emerging and efficient work force. But

with the battling nations recruiting and conscripting thousands of new

troops, and the armies brutally fighting each other with no end in

sight, the strain on the medical department continued undeterred both in

the Eastern and Western theaters of operation.

In the East, in late January, Joseph Hooker relieved

General Burnside. But unlike his predecessor, Hooker concentrated on

bringing the health of the army up to acceptable standards, for he saw

how diarrhea, scurvy, and various fevers were devastating his soldiery.

Dr. Letterman had always believed that a good diet, (including ample

vegetables) paired with enforced sanitation and better cooking methods

would strengthen the army's stamina and morale. By April Letterman's

policies, backed by General Hooker's authority and common sense, caused

the rate of sickness to drop; and in turn the physical and mental spirit

within the hundreds of old and new regiments rose accordingly.

Well prior to the start of the spring campaign, Dr.

Letterman began to prepare for the upcoming battles. As his hands were

already full, he appointed two medical inspectors to act under him

within the Potomac army, and ordered that each corps medical director

add a similar officer to their units. During the previous winter,

medical boards had been established to examine and weed out deficient

surgeons, and by March he had again outlined how he wished his

department to operate during military engagements.

Immediately before the army decamped, Letterman, in

order to keep 8,000 sick soldiers near their commands, set up tent

hospitals along the railroad from Fredericksburg to the Aquia and

Potomac Creek depots. As expected, maneuvering soon began between

Hooker's and Lee's armies and the resulting combat at the Battle of

Chancellorsville, fought on May 1-4 threw 9,700 wounded Federals into

Letterman's system. These casualties had to be funneled from the

confused battlefield through Fredericksburg, then subsequently across

the Rappahannock River. Once over that barrier the men were placed

aboard trains and then run along a single track to the Potomac River and

thence by boat to Washington. [24] The evacuation of

these injured did not go as smoothly as it should have, and the army's

medical service was not, in this case, a perfect model of efficiency.

Due to the confused state of affairs during the fighting, and the

general inept handling of the army by Hooker, many small things went

wrong for Letterman's people. Field hospitals were frequently adjusted

owing to artillery fire or an unexpected enemy breakthrough. One doctor

in the Third Corps complained that his division facility had to be

uprooted five times, and in the end, 1,200 badly injured Yankee soldiers

eventually became captives of Lee's victorious forces. [25] Another embarrassment for Letterman was the admission

that a few of his physicians had cowardly run off during combat leaving

their charges, while others had become intoxicated on government issued

stimulants stockpiled for the sick and wounded.

Inasmuch as many of these minor complaints were true,

several unusual situations complicated the big picture at

Chancellorsville which could not be wholly blamed on the medical

department. For one, the defeat of the Union army inherently created an

atmosphere of confusion and fear as doctors and attendants exerted

themselves to avoid being overrun and captured. The rapid pullbacks and

retreats during the daily actions forced the U.S. ambulance corps to

hastily evacuate its bleeding cargoes over a long and rough 25-mile road

to the safety of more permanent corps hospitals in the rear. Moreover,

Hooker's very orders added to the load, when he prevented medical wagons

and all but two ambulances per division from crossing the Rappahannock

when the army marched toward Chancellorsville. Paralleling that order,

no stretchers or stretcher bearers were allowed over the river until

April 30, when shell fire had already forced the abandonment of at least

one hospital. [26]

In his final assessment, Dr. Letterman professed that

when looking at the entire operation, the frequent dislocations had been

reasonably managed, and his staff had performed as well as could be

expected under the circumstances. In acknowledging their valuable

services, he was especially pleased to report that in almost all cases

the 1862 field hospital directives of October 4 and 30 were carefully

followed and adhered to. This resulted, even under the difficulties

encountered, in generally excellent care and comfort provided to the

majority of the wounded of that battle.

In the most serious cases, where patients were too

hurt to be transported far, Letterman chose to keep them with the army

instead of dispatching them to Washington. In accordance with this

ideology, he set up large tent hospitals at Potomac Creek where the men

could be tended by their own physicians. Of these encampments, he

remarked:

"I have never seen better hospitals. This opinion

was entertained by the professional and unprofessional men who visited

them, and I regretted the necessity which compelled me to break them up

about the middle of June in consequence of the march of the Army into

Maryland and Pennsylvania."

The Battle of Chancellorsville has often been called

"Lee's greatest victory." This may be so, but it led him down the

path to his most serious defeat, at Gettysburg, in the summer of that

same year.

Only speculation could infer what thoughts possessed

the mind of Jonathan Letterman as the Army of the Potomac marched

northward in hot pursuit of the resolute Confederate invaders. It had

been barely a month since he and his colleagues were mired knee deep in

thousands of casualties from a severe battle; now, they seemed to be

headed for another and possibly even more terrible confrontation.

The Union march to intercept General Lee was well

underway when it was announced that General George G. Meade, the Fifth

Corps commander, had replaced General Hooker as head of the army. This

came on June 28 when all of the corps except the Sixth, were within a

day's hard walk or less of Gettysburg. The march from Falmouth, Virginia

on June 12 to the very doorstep of Pennsylvania by the end of the month

had been one of the hardest on record for Lincoln's grand force of

approximately 100,000 men. Ruefully, not all of them made it to

Gettysburg.

Thousands dropped out and straggling climbed to new

heights, all in relation to the amount of dust and heat, or the number

of miles covered during a particular day or night. Scores of veterans

fell by the roadsides totally exhausted or dead, caused by the 25-30

mile per day treks. By the time the campaign ended in late July, many

regiments could claim a travel agenda of between 500 and 600 miles

covered on foot, while dining on hardtack, salt pork, and coffee, and

with water taken where it could be found. The animals suffered too.

Meade's force required in excess of 700 tons of supplies daily,

therefore over 4,000 wagons accompanied it. If the needs of the cavalry

and artillery are calculated, this amounted to over 50,000 horses and

mules present for duty. Meshed into this huge coalition were Dr.

Letterman's ambulances and two horse medical wagons, adding another

1,017 vehicles. [27]

When the army left the Fredericksburg area between

June 12 and 14, Dr. Letterman commenced the removal of 9,025 wounded and

sick with their supplies, from that city up Aquia Creek and on to

Washington. This was successfully accomplished in short time. Meanwhile,

as the Army of the Potomac skirted the capital on its northerly route,

Letterman arranged for 25 wagon loads of battle supplies to be packed

and sent to Frederick under the direction of Surgeon Jeremiah Brinton.

By the day General Meade assumed command, Brinton had traveled even

farther to Taneytown, Maryland, Jeremiah Brinton where headquarters were

then located. There the wagons remained, under Meade's orders until

after the Battle of Gettysburg. [28] Even more

disturbing was a decree issued several days earlier, on June 19, before

Meade's ascension. In it General Hooker directed that the "allowance of

transportation" that Letterman had deemed necessary for the medical

department in the fall of 1862, was to be reduced. This went against the

director's opinion and argument, and it compelled him to send away a

large portion of the "hospital tents, mess-chests, and other articles

necessary upon the battlefield, and proved," said Letterman, "as

I foresaw it would, a source of embarrassment and suffering, which might

have been avoided." [29]

In another, and more controversial move, Meade, to

keep the army's back door open, restricted the baggage of his force very

stringently. He directed that "Corps Commanders and the Commander of

the Artillery Reserve will at once send to the rear all their trains

(excepting ammunition wagons and the ambulances), parking these between

Union Mills and Westminster." This order came on July 1, prior to

any knowledge of General John F. Reynolds' collision with the Rebels at

Gettysburg. A day later, Dr. Letterman was frustrated to learn that

"while the battle was in progress, the trains (including the hospital

wagons and the trains of battle supplies, under charge of Dr. Brinton)

were sent still further to the rear, about twenty-five miles distant

from the battle-field." [30] This left the medical

staff of each corps with only ambulances and medicine wagons on hand

(which were already in short supply) to sustain the needs of many

thousands of wounded for almost a week. Without the correct number of

tents, tools, cooking utensils, special rations, and other supplies

normally called for immediately after combat, sick and injured soldiers

would suffer needlessly. Surgeon Justin Dwinell, the medical officer in

charge of the Second Corps hospitals, was only one of many who

complained of a lack of tents, blankets, provisions, axes, shovels,

cooking utensils, and medical stores before July 7, when the long

awaited trains finally arrived. Regarding this situation he affirmed:

"Nothing but to gain a victory should ever prevent these wagons from

following the ammunition train."

Thus the hundreds of medical officers and their

associates assigned to the Army of the Potomac were once again in debt

to the U.S. Sanitary Commission and other relief organizations who came

to their immediate aid with foodstuffs and other assorted materials.

Oddly, in contrast to six of Meade's corps, one, the Twelfth, did not

receive or respond to this order, hence none of its normal compliment of

hospital wagons was sent to the rear. Accordingly, this unit was able to

evacuate, bathe, dress, and feed its wounded completely within six hours

of the end of the battle. [31]

Allowing for the subtraction of thousands of Union

and Confederate soldiers who were sick, or had been previously wounded,

including those that had straggled or deserted, the two armies were

still able to field close to 150,000 troops during the three day battle

at Gettysburg. Of this number, 14,529 Northern and 6,802 Southern men

were left more or less seriously injured in U.S. hands within the

numerous field hospitals situated in and around the prosperous borough.

This 21,331 total was only about 6,700 bodies less than the 1860

population of Adams County, Pennsylvania, the locale where the battles

had raged. Intrinsically, both sides usually underestimated the

casualties, as scores of slightly hurt men were never counted, or stayed

in ranks with their units, or otherwise slipped through the cracks of

the reporting mechanisms. [32]

Even before the first projectiles flew on July 1, a

field hospital had been established in the town of Gettysburg as a

result of the arrival of General John Buford's 1st Cavalry Division on

June 30. A local citizen, Robert G. McCreary confirmed this, when on

that date a medical officer "requested accommodations for six or

eight of the command who were sick." The railroad depot on Carlisle

Street was opened for that purpose, and twenty beds were set up within

the structure. It was only hours later that the depot began admitting

wounded cavalrymen as Buford's division struggled to hold its positions

beyond Gettysburg. Later in the day as the battle of July 1 escalated,

and the infantry and artillery units began to retreat, the injured

troopers were removed from the depot to the Presbyterian Church on

Baltimore Street. Accompanied by several of their doctors, these men

like many of their comrades, fell into Confederate hands by sunset. The

depot itself was then secured by surgeons of the First Corps, and it,

the express office and nearby buildings became field hospitals for a

portion of that Corps' casualties. [33]

The story of the railroad depot might reflect the

general situation of many of the early field hospitals at Gettysburg.

During the first two days of fighting, battle lines were more or less

fluid and the ever-changing deployments of the combatants, and overshot

enemy artillery fire often forced the repositioning of aid stations and

field hospitals.

Throughout the day on July 1 as the First and

Eleventh Corps clashed with Confederates north and west of Gettysburg,

the aid or dressing stations, usually manned by a regimental

assistant-surgeon and his attendants, followed their respective units

back and forth as the battle raged and waned one way or the other. These

aid stations were the first stops for the "walking wounded" or any

seriously injured Federal who was fortunate enough to be reached by the

stretcher-bearers. In recalling the earlier discussion of this subject,

it should be remembered that as of October 1862, all medical personnel

had particular assignments on the day of battle. Even before the opening

shots, surgeons, assistant-surgeons, operators, recorders, hospital

stewards, cooks, ambulance drivers, litter bearers, nurses, teamsters

and other attendants, knew their posts and duties. So as the impassive

missiles tore men from the regimental firing lines, these crippled and

blood soaked individuals headed for safe zones, knowing that the medical

department was ready and waiting. The initial stop was at the dressing

stations where literally, "first aid" would be administered to all

injured parties. No operations were performed at these primary sites.

The doctor there would simply stabilize and bandage the wound then

direct the ambulatory patient to his correct field hospital in the

army's hinterland. Concurrently, other attendants gathered the more

seriously injured to an ambulance collecting point for removal by

wheeled conveyances to the divisional field hospitals.

These division ambulance trains consisted of 30 to 50

vehicles of various types all for the transportation of the wounded.

Included too were 10 or 15 medical supply wagons unless, as was in the

case of the Battle of Gettysburg, these trains were jettisoned. Each

ambulance carried four stretchers or hand litters, plus a supply of

bandages, lint, astringents, chloroform, whiskey, brandy, condensed

milk, and concentrated beef soup. A regiment had approximately eleven

men attached to it from the ambulance corps, counting the sergeant in

charge. [34]

In the late afternoon of July 1, after hours of some

of the most severe combat of the battle, units of the Union's First and

Eleventh Corps retreated to reserve positions on Cemetery Hill and

Cemetery Ridge just south of Gettysburg. In consequence of the rapid

redeployment of these corps, the ambulance teams were unable to recover

all of the wounded individuals from the 1st and 3rd Divisions of the

Eleventh, nor from all three divisions of the First Corps. During the

long and eventful day medical directors and surgeons of the two corps

set up sheltered division hospitals near to and in the borough itself.

They seized the Lutheran Theological Seminary and college buildings, the

railroad depot and express office, several large warehouses, the

Washington House Hotel, the Union School, the county courthouse and

almshouse, and several churches. But even this was not enough, and an

overflow of perhaps 400-450 men ended up as patients in private

dwellings. When the troops at the front begun their withdrawal about 5

p.m. the ambulance drivers and attendants went right along, thus ending

the evacuation of U.S. casualties on the day's field by Union personnel

until July 4. If not found and taken up by Southern squads, which many

were, the abandoned wounded remained on the contested ground until after

the Confederate retreat. By dusk of that day the village was in sole

possession of the Rebel army, as were the Federal hospitals, and several

thousand prisoners, both hurt and not. When it was clear that Gettysburg

would be given up to the Confederates, some of the nearly 4,000 Northern

casualties were hurried out of town to safer locales. A handful of

doctors chose to stay with their men, usually one or two in each

facility; the balance joined the retreat and were directed to new field

hospitals then being formed south and southeast of Cemetery Hill.

Of this tragic and fearful time, Dr. Jacob Ebersole,

a 19th Indiana Infantry surgeon, who remained with his charges,

recalled:

"[It] was just before sunset. Looking from the

upper windows of the hospital, [at the railroad depot] I could see our

lines being repulsed, and falling back in utter confusion. Our front was

entirely broken, the colors trailing in the dust, and our men falling on

every side. The enemy were enveloping the town from that side, sweeping

past the hospital and completely filling the streets." [35]

By midnight, any of the first day's casualties that

had been fortuitously rescued before or during the collapse of the Union

forces, were deposited in makeshift temporary hospitals at farmsteads

along the Baltimore Pike and the Taneytown Road. Obviously the director

of the First Corps, Dr. T.J. Heard had learned his lesson, for he placed

his new facilities well out of range of enemy missiles. The biggest

concentration of this Corps' casualties were, by July 2, clustered

around the "White Church," three miles out on the turnpike to

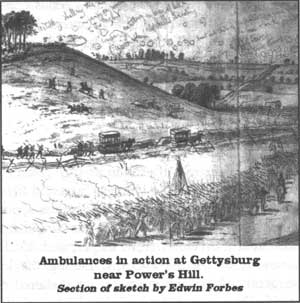

Westminster and Baltimore, and on farms contiguous. The three Eleventh

Corps divisions were congregated on the Elizabeth and George Spangler

place, (not out of artillery range) east of that pike and just

south of Power's Hill, where they remained until early August. It is

surprising that inasmuch as the Eleventh Corps met with disaster,

confusion, and some demoralization on July 1, its medical staff managed

to regroup and rebound quickly; they set up and maintained a cohesive,

well regulated field hospital very near the battleground, although not

completely out of harm's way. [36]

|

|

Ambulances in action at Gettysburg near

Power's Hill. Section of sketch by Edwin Forbes

|

Just what was it like in one of these hospitals as

its staff struggled to stabilize the occupants, while the battle raged

nearby? A U.S. Volunteer surgeon has left this excellent account of the

scene in one such place.

"Behind a partially protected hill there is a field

hospital; the lines of stretcher-bearers and ambulances mark the way to

it. There are a few tents and rudely improvised tables; at the latter,

calm faced men, with bloody hands and instruments, are at work. Wounded

men are lying everywhere. What a horrible sight they present! Here the

bones of a leg or an arm have been shattered like glass by a minnie

ball. Here a great hole has been torn into an abdomen by a grape shot.

Near by see that blood and froth covering the chest of one choking with

blood from a wound of the lungs. By his side lies this beardless boy

with his right leg remaining attached to his body by only a few shreds

of blackened flesh. This one's lower jaw has been carried entirely away;

fragments of shell have done this cruel work. Over yonder lies an old

man, oblivious to all his surroundings, his grizzly hair matted with

brain and blood slowly oozing from a great gaping wound in the head.

Here is a bayonet wound; there a slash from a saber. Here is one bruised

and mangled until the semblance of humanity is almost lost - a squadron

of cavalry charged over him. This one has been crushed by the wheel of a

passing cannon. Here is one dead, and over there another; they died

while waiting for help that never came. Here are others whose quivering

flesh contain balls, jagged fragments of shell, pieces of iron, and

splinters of wood from a gun blown to pieces by an exploding shell, and

even pieces of bone from the head of a comrade who was torn to pieces by

the explosion of a caisson. The faces of some are black with powder;

others are blanched from loss of blood, or covered with the sweat of

death. All are parched with thirst, and many suffer horrible pain; yet

there are few groans or complaints. The sum of human agony about was so

great that no expression can describe it. Although the surgeons work

with marvelous haste, the number demanding their attention seems always

to increase; some come hobbling by aid of an improvised crutch, others

are supported by comrades, while the bloody stretchers and ambulances

ever deposit their ghastly freight. Occasionally a shell flies over

head, its scream sounding like that of a fiend rejoicing over the

horrors below. The great diapason of the battle sounds loud or low, as

the contending hosts shift places on the field; [while] cowardly

stragglers gather about, spreading stories of disaster and

defeat."

Heavy fighting broke out near 3 p.m. on July 2 and

continued almost unabated until nearly midnight. Casualties were high.

By day's end the Union army suffered over 8,500 wounded and 1,825

killed. Dedicated ambulance work was needed well into the evening, but

as some ground was lost to the Rebels, it was impossible to collect each

and every downed soldier. The ambulance corps was by most accounts,

skilled and efficient in its work, having enough practical experience

and drill since late 1862 to be able to handle any ordinary situation.

On the average at Gettysburg each infantry corps mustered between 80 and

100 ambulances, plus medical wagons, etc. The Eleventh for one, counted

100 ambulances, nine wagons, 270 men and 260 horses. [37]

Several valuable descriptions of the activities of

the ambulance corps on July 2 have survived. One, that of Dr. Joseph

Thomas, 118th Pennsylvania, gives an interesting perspective of the 1st

Division, Fifth Corps.

"About eleven o 'clock at night the ambulances

were busy collecting and carrying to the rear great loads of mangled and

dying humanity. The wagon-train, with tents and supplies, had not yet

arrived, and the wounded were deposited on the ground....As they were

removed from the ambulances they were placed in long rows, with no

reference to the nature or gravity of their injuries nor condition or

rank. Friend and foe alike, as they had been promiscuously picked where

they had fallen, were there laid side by side in these prostrate

ranks.... Soon the ambulances ceased their visits...[to await] as dawn

should appear to furnish light for the painful work. Opiates were

administered to alleviate pain, and water supplied to appease their

thirst.... Sounds of pain and anguish, invocation and supplication,

singing, and even cursing by some in their delirium or sleep,... At last

morning dawned, and at the same time orders were received to remove the

wounded farther to the rear and out of range of the enemy's

batteries,... [38]

But for a more mechanical look at the evacuation,

there is this piece written by ambulance chief Lieutenant Joseph C. Ayer

of the same corps as Dr. Thomas.

"As soon as the division was placed in position

all my stretcher men, under their lieutenants and sergeants, were sent

to the front to follow their respective regiments; leaving one

lieutenant and three sergeants in charge of the train. I conducted the

train to a point two hundred yards in rear of the second and third

brigades, where it was rapidly loaded with severely wounded. Owing to

some misunderstanding there was a delay in locating the division

hospital and the wounded men remained in the ambulances about an hour,

when the hospital was established and the wounded unloaded. The

ambulances then commenced regular trips to the battlefield and were

constantly at work during the night."

Lieutenant Ayer further relates that shortly

afterward he too was called on to relocate the injured to a more secure

region. [39]

The officer in charge of the Second Corps recovery

teams was Captain Thomas Livermore, who had been assigned the position

of "chief of ambulances," only two days earlier on June 30. In an

instant Livermore had gone from a company line officer in charge of 30

men to, as he reveals, a "command [of] two or three hundred men, a

dozen officers, and a large train;...." He added that he went from

trudging along dusty roads with his foot soldiers, to riding away on a

"spirited and strong-limbed horse." Livermore described his new

organization in detail:

"The ambulance corps consisted of three trains,

one for each division of the army corps. Each train consisted of

forty-two horse ambulances, [about three to a regiment] with a few for

the artillery, several wagons with four horses to carry forage and

rations in, and a forge wagon for repairs and horseshoeing, with several

old-style four-horse ambulances. The men were selected proportionately

from the regiments, and consisted of a driver for each ambulance and

wagon, two stretcher-carriers for each wagon, and several blacksmiths

and supernumeraries.... The total force of the ambulance corps [Second

Corps] was, in round numbers, 13 officers, 350-400 men, and 300 or more

horses, with a little over 100 ambulances and 10 or 12 forage and forge

wagons;... Each two-horse ambulance was a stout spring wagon,...with

sides a little higher than theirs along each side. Inside this wagon

were two seats the whole length,...stuffed and covered with leather.

Hinged to the inner edges of each of these seats was another

leathercovered seat, which could be let down perpendicularly so as to

allow the wounded to sit on the first seats facing each other, or could

be raised and supported horizontally on a level with the first seats,

and, as they filled all the space between the first seats, thus made a

couch on which three men could lie lengthwise of the

ambulance....

"On each side of the ambulance there was hung a

canvas-covered stretcher to carry the wounded on, and the whole

ambulance was neatly covered with white canvas on bows. The horses were

all good ones and well kept; the men were stout, and the officers were

intelligent."

In his memoir, Captain Livermore purported his

"superintending and collection and dispatch" of the wounded of

the Second Corps from after twilight till midnight of the July 2, then

once again on July 3. On the second his trains parked in proximity to

the farm of Sarah Patterson on the Taneytown Road where the 2nd Division

hospital was laid out under Surgeon Dwinell. Dwinell later acknowledged

"the faithful and efficient services rendered by the

ambulances...[and] the great care and consideration they manifested for

the wounded." Initially the human cargo of the Corps was dropped off

at Patterson's. But the following day, Livermore was directed by the

Corps' medical director, Dr. A.N. Dougherty to pick a sheltered location

for a "general field hospital, where all the wounded could be carried

and provided with shelter and treatment until the battle was over."

He selected a spot on Rock Creek about a mile-and-a-half down stream

from the Baltimore Pike bridge. From that time on all of the casualties

of the Second Corps were removed from the Taneytown Road farms and

fields and relocated within the grounds of the new site. [40]

What emerges is that for many of the corps, the

primary hospital establishments had been placed absurdly close to the

front, eventually causing all to be uprooted and settled elsewhere. As

Dr. Dwinell testified: "We have almost invariably had occasion to

regret having...our Hospitals too near to the line of battle."

|

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

In relation to these aforementioned places, Dr.

Justin Dwinell, who was surgeon-in-charge of the Second Corps field

hospitals, left his peers with an official version of the activities

surrounding them. In this report he concedes that the overall debility

of the troops after the "protracted daily marches," caused them to be

ill prepared "to bear up under the shock of wounds and the subsequent

exhaustion of the system." As to the field hospitals on July 2, his

2nd Division was at Sarah Patterson's stone barn, the 3rd Division

camped at a barn 300 yards away on the same road, and the 1st Division

was adjacent to the Granite School House to the right and rear of the

3rd. The last named was soon shelled out of position by Rebel batteries

and was moved to McAllister's Mill on the Baltimore Pike.

Again as in other corps, rations were hard to obtain,

and cooking utensils were borrowed from nearby farmers, all due

primarily to the absence of the supply trains. The operators at

Dwinell's establishment kept up with their surgery at four tables until

after 4 p.m. when the accumulation of so many wounded forced them to

lose momentum. On the 3rd food was obtained for the 500 casualties at

his hospital. By 1 p.m. on July 3 the wounded were in motion to the

second position spoken of by Captain Livermore, which was a mile and a

half down the Taneytown Road and on the farm of George and Anna Bushman,

east of the farmhouse in a bend of Rock Creek. All injured in the three

divisions were evacuated by nightfall. The operations continued, but

there was a great need for tents, straw, transportation, shovels, axes,

blankets, and eatables. On the fourth, 6000 rations of tea, coffee,

sugar, soup, crackers, salt, candles, pork, and 3000 pounds of beef on

the hoof were provided. The U.S. Sanitary Commission added soft bread,

wines, oranges, lemons, and other dietary items, plus clothing.

This hospital changed its locality to higher ground

about July 22 and into a clover field across Rock Creek and nearer to

the farm buildings of Jacob Schwartz. Altogether this facility cared for

3,260 Union and 952 Confederates, making it the largest field hospital

extant after the battle. Dwinell had between 17 and 30 doctors available

to him at various times between July 4 and August 8 when the hospital

closed. He emphatically voiced his distrust of the skill and dedication

of civilian volunteer and contract surgeons, citing them as too

"unreliable." Dr. Dwinell complained too of the hundreds of able-bodied

skulkers that invaded these safe areas, and who "consume the food and

occupy the shelter provided for the wounded." In that hospital there

were 437 deaths, of which 192 were Southerners. In conclusion, Dwinell

felt the medical department of the Second Corps was made up of practical

men of large experience and observation. "It is thoroughly organized,"

said he. "Every Surgeon knows beforehand whether he is to remain on

the field or return to the Hospital in the time of Battle. In either

case he knows the part he is to perform. They have become familiar with

their duties....they were indefatigable in the performance of their

labors,...and did all in their power to alleviate the sufferings of the

wounded." Ending his manuscript, he made this observation:

"[P]robably at no other place on this continent was there ever

congregated such a vast amount of human suffering. [41]

Justin Dwinell's last quote is correct. From one

single calamity the United States had never been exposed to as many

casualties caused by any natural or human incited event. It is also

likely that his statement still holds true today. The literally hundreds

of eyewitness versions that describe the horror of Gettysburg would

alone fill a large volume. Everyone who saw the catastrophe was

singularly impressed and often aghast at the hideous sea of misery which

surrounded the community. Within seventy-two short hours, over 7,100

people had been sent to eternity, while 33,300 more remained alive

weltering in their own blood and waste, anxiously awaiting and even

begging for medical treatment. Of these, several additional thousands

shortly perished.

One of the thousands of idle spectators who traveled

to Gettysburg in the wake of the battle was a preacher named Cort from

Somerset, Pennsylvania who, like so many, could not resist the impulse

to set down their recollections of a visit to hell.

"The scenes of suffering among the many thousands

of wounded of both the Union and Confederate armies which came under my

observation in the few days I spend in and about Gettysburg on that

memorable occasion, are altogether indescribable. Human language is

inadequate to do it justice. The horrors of war were revealed in a way

that was sickening to the heart. The ghastly wounds, the moans and cries

and screams of anguish, the ravings of those whose reason had been

dethroned, and the appeals for water to allay thirst and morphine to

ease pain, were such as to move the stoutest hearts. One of the streams

had overflowed its banks, and a number of wounded confederates were

drowned and their bodies swept away by the raging waters. Great piles of

amputated limbs lay around. Experienced surgeons and medical students

fresh from the schools were at work like so many bloody butchers. The

putrid and swollen remains of slaughtered men and horses filled the air

with malaria, which soon brought disease and death to visitor from all

parts of the country, as well as to the inmates of the crowded

hospitals. Suffering and death were everywhere, and the efforts put

forth for alleviating the latter, though rendered by hundreds of willing

hands, seemed as but drops to a bucketfull when compared to the vast

aggregate all about us." [42]

Preacher Cort saw the field on July 8 after almost a

week of aid had been administered to the 22,000 wounded left behind by

the two armies. An active imagination might attempt to view the problems

encountered even earlier when the medical directors and surgeons were,

in the constant shifting of hospitals, doing their utmost to render

comfort to their wretched patients under more extreme and adverse

conditions.

At the end of the third day not only had the First,

Eleventh and Second Army Corps field hospitals been safely reestablished

as previously encountered, so had the Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Twelfth

Corps. The Third and Fifth, after fierce fighting on the Union left

during July 2 had also mishandled the positioning of their hospitals on

the day of battle. This tactical error required realignment from spots

carelessly selected on farmsteads, in woods, and in meadows along the

Taneytown Road and out toward the Baltimore Pike, to protected and more

permanent camps south and southeast of Gettysburg. The Third Corps' two

divisions were lastly settled south of and along White Run 300 yards

from its junction with Rock Creek, a place southwest of the farm

buildings of Jacob Schwartz and east of those of Martha and Michael

Fiscel. The site was reportedly high, dry and "airy," with plenty of

water nearby. However, Surgeon J.W. Lyman, 57th Pennsylvania, described

part of it as "finely wooded and [on a] shady slope."

The Third's medical director Thomas Sim was not

present; he was ordered to accompany Corps commander Daniel Sickles, who

had lost a leg in the fray, to Washington. Under Surgeon Thaddeus

Hildreth this camp handled about 2600 U.S. wounded, and 259 of the

enemy, and closed its operation on August 8. One division there reported

813 casualties - of these there were 97 operations performed, 53 being

amputations. [43] Immediately after the battle, an

army physician stationed at this site declared that most of his patients

were "lying on the wet ground without any shelter whatever. The

people in this district have done nothing for them."

On July 9 this same Pennsylvania doctor, William

Watson, was posted as one of the operators of his division and with

seven other medicos serviced the ills of 813 wounded and 100 captured

Confederates, who were "in a most distressing condition." He indicated

these facts on July 18: "The mortality among the wounded is fearful -

caused principally by Gangrene, Erysipelas, Tetanus and Secondary

Hemorrhage. Our secondary operations have been very unfavorable. Most of

the cases die." [44]

The U.S. Fifth Corps, like its July 2 companion

fighting force, the Third Corps, grouped all three divisions much too

near the battle lines, mainly around the Jacob Weikert farm and fields

adjacent along the Taneytown Road, just in rear of the Round Tops. One

location was about a half mile from the base of Big Round Top and

contained 250-300 casualties from the 1st Division. The 2nd Division

under Assistant Surgeon John S. Billings commandeered the Weikert place,

and with three Autenreith medicine wagons, and the farmer's food on

hand, he "performed a large number of operations, [and] received and

fed 750 wounded." He too acknowledged assistance from the Sanitary

Commission.

On July 3 at 7 a.m. orders led to the abandonment of

this farm hospital to another site, "in a large grove of trees,

entirely free from underbrush, on the banks of a little creek, about a

mile from the Baltimore Pike." Two thousand rations arrived, and

with some common infantry shelter tents the suffering men were arranged

as comfortably as possible. The fifth of July brought up many of the

medical supply wagons, so tents and other articles allowed the 800

injured of this division to be protected and fed. On the same day,

Jeremiah Brinton of the transportation section finally arrived with

Letterman's special supply train, and quickly distributed the valuable

material to all of the corps' hospitals. Dr. Billings alone received 17

large hospital tents and many tent flies, which were immediately

erected. Tools were his greatest need; a few had been procured from

local farmers, and were put to use digging graves and latrines. Surgeon

Cyrus Bacon, a colleague of Billings, also left a memoir of service in

the Fifth Corps hospitals. He states that only the most serious cases

went into tents, and that many of the worst wounds caused by the Minie

bullet resulted in Pyaemia setting in. It was one repercussion after

capital operations and "almost invariably proved fatal." Bacon

underscored the reality that of the eleven surgeons on duty, at

different periods, eight were taken ill, including the narrator himself,

who was seized with an inflammatory diarrhea.

The final dispositions of these hospitals, under Dr.

A.M. Clark were as follows: 1st Division, on Sarah and Michael Fiscel's

farm, north of the house and south of Rock Creek, with the barn used for

the worst cases; 2nd Division, south of Jane Clapsaddle's house, across

Little's Run; and 3rd Division one-half mile west of Two Taverns, on

Jesse and Ann Worley's farm. The three sheltered 1,400, out of a total

Fifth Corps loss of 1,611. [45]

The most fortunate body of Federal troops in service

at Gettysburg was the Sixth Corps. Its medical director, Charles

O'Leary, assigned Dr. C.N. Chamberlain to manage the hospitals which

superintended about 315 wounded. Many of the Corps' infantrymen were

thoroughly worn down by a rapid forced march of 32 miles prior to

reaching Gettysburg. Previously it had covered 100 miles in four days,

yet percentage-wise, few men had fallen out of the columns. Since it was

not heavily engaged the Corps suffered only 27 killed and 185 wounded.

[46] Yet the field hospital on the 165 acre farm of

John and Suzannah Trostle along Rock Creek, cared for an assortment of

maimed Southerners and an overflow of men from the Fifth, Third, and

Second Corps. The injured here received especially good treatment and

attention, and had quarters in tents and in Trostle's house, barn, and

outbuildings, although one soldier complained of the lack of enough

food. In early August, as was usual, this facility was closed, and the

remaining patients transferred to Camp Letterman east of Gettysburg or

to the railroad for shipment to other governmental general hospitals

miles away. [47]

|

|

George Bushman House, Twelfth Corps Hospital

|

The two divisions of the Twelfth Corps fought

principally on the right flank of the army and tallied 406 wounded in

the 1st and 397 in the 2nd, these mainly shot while entrenched in the

vicinity of Culp's Hill. Strangely, their permanent field hospitals were

pitched along a farm road leading from the Baltimore Pike past Power's

Hill to the lower crossing of Rock Creek, and east and north of the

house of George and Anna Bushman which stood nearby. In sizing up the