|

"UNION ARTILLERY ON JULY 3"

Bert Barnett

The early afternoon of July 3, 1863, was hot, humid

and uncomfortable. With the temperature destined to reach 87 degrees by

2 p.m., [1] soldiers of the Army of the Potomac lay

sprawled about Cemetery Ridge, seeking whatever relief could be found

from their enemy of the moment, the unrelenting summer sun. Some had

erected crude shelters, using muskets and shelter-halves to escape the

direct rays beaming down upon them. [2] These proved of

dubious value, and many of the men had simply gone to sleep. As Lt.

Frank Haskell, ADC to General John Gibbon, recalled:

We dozed in the heat, and lolled upon the ground,

with half open yes...A great lull rests upon the field. Time was heavy;

- and for want of something to do, I yawned and looked at my watch; - It

was five minutes before one o'clock. I returned my watch to its pocket,

and thought possibly that I might go to sleep, and stretched myself out

accordingly.

A sharp report abruptly interrupted his sleep:

What sound was that? -There was no mistaking it!-

The distinct sharp sound of one of the enemy's guns, square over to the

front, caused us to open our eyes and turn them in that direction, when

we saw directly above the crest the smoke of the bursting shell, and

heard its noise.-In an instant, before a word was spoken, as if that

were the signal gun for general work, loud, startling, booming, the

report of gun after gun, in rapid succession, smote our ears, and their

shells plunged down and exploded all around us.- We sprang to our feet.-

In briefest time the whole Rebel line to the West, was pouring out its

thunder and iron upon our devoted crest. [3]

In preparation for General James Longstreet's

large-scale infantry assault to follow, a massive cannonade of nearly

150 Confederate artillery pieces, designed to cripple the Union

artillery and clear the way for the infantry, had begun. [4] How effective would the Union artillery response to

this challenge be? In large part, victory or defeat rested upon whether

the Union gunners could hold their own against this onslaught.

|

|

Meade's Defense, Bg. Hunt's fire support

coordination plan 03 July 1863 (click on image for a PDF

version)

|

Confederate General Robert E. Lee knew the value of

artillery upon high ground in a defensive situation. His experiences at

Malvern Hill, in defeat, and at Chancellorsville, in victory, had shown

him the tremendous power of artillery massed against infantry. As he now

prepared an infantry attack against positions well-covered by artillery,

he knew the Yankee batteries must be reduced for his assault to succeed.

He issued orders to his artillery commanders that reflected this.

Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, acting chief of artillery for

Longstreet's corps, remarked that:

My orders were as follows. First, to give the

enemy the most effective cannonade possible. It was not meant simply to

make a noise, but to try and cripple him-to tear him limbless, as it

were, if possible...[T]hen further, I was to "advance such artillery as

[could be used] in aiding the attack." [5]

With proper concert of action between the Confederate

artillery, hammering away at the Union guns and the Confederate infantry

breaking the Union infantry line, success was deemed possible. Much

depended upon neutralizing the Federal guns.

On the late morning of the 3rd of July the Federal

artillery line extended nearly two miles in length, from Little Round

Top, north to the area of Cemetery Hill. Deployed on this position were

some twenty-six batteries, representing 132 guns. In the rear of the

line, in the reserve park, were twenty more batteries with 112 more

pieces. [6]

|

|

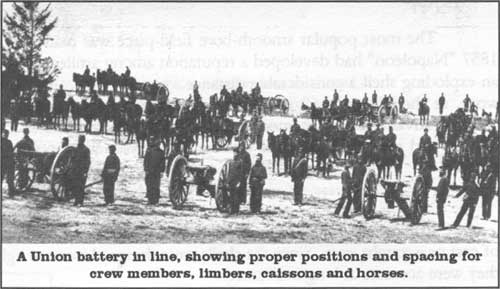

A Union battery in line, showing proper

positions and spacing for crew members, limbers, caissons and

horses.

|

The types of guns in this line, as well as the other

artillery employed by the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg, were rifled

or smoothbore muzzle-loaders (Map 1). While the ammunition was not

interchangeable between them, four basic types of ammunition were used:

solid shot, common shell, case shot, and canister.

Solid shot, known as "bolts" in rifled guns, were

useful against structures or enemy gun carriages. They could also be

used effectively against massed troops, to demoralize and weaken

infantry units at long range.

Two types of exploding shells, common shell and case

shot, or shrapnel, were available for antipersonnel use. While shells

could be fired at targets a mile distant, they were much more effective

at intermediate ranges of approximately 1200 yards down to 600. Both

were hollow, cast-iron projectiles containing a bursting charge of

powder ignited by a fuse or percussion primer. [7]

Depending upon the nature of the intended target, the shell would burst

on contact or in the immediate area, and scatter fragments about. Common

shells were also useful for igniting fires, and were the ammunition of

choice when attempting to burst an enemy's limbers or caissons during

counter-battery fire.

Where common shells contained only a bursting charge,

case shot also contained a handful of round lead musket-balls. This

improved the efficiency of the exploding shell as an antipersonnel round

at intermediate distances. For close-up work of 500 yards or less,

however, canister was the ammunition of choice. As the name suggests, a

canister round was a tin can containing a number of round metal balls

(27 cast-iron roughly golf-ball size in a 12-pounder smoothbore, [8] 110 lead large marble-size in a rifled pieces). [9] Upon firing, the tin can was blown apart and the

individual balls flew freely out the muzzle of the gun. Canister was the

last-ditch defensive round in the artillery service, as the range of an

infantryman's rifle-musket was approximately 500 yards.

With the exception of canister rounds, all other

projectiles fired from smoothbore pieces were round. As they were fired,

a smoothbore would "ring" as well as boom, producing a secondary sound

not unlike that of a church bell. This was the result of the

loose-fitting projectile literally bouncing its way out the barrel. This

loose fit, while helpful in the loading, cost the smoothbore somewhat in

accuracy.

The most popular smooth-bore field-piece was made of

cast bronze. The twelve pounder, Model 1857 "Napoleon" had developed a

reputation among artillerists as a fine weapon. A Napoleon could throw

an exploding shell a considerable distance - nearly a mile. Napoleons

were often preferred for closer range work, as their larger 4.62 inch

diameter bores meant that more metal went downrange with each shot.

Another advantage of the smoothbore was that it fired canister rounds

more accurately than a rifled gun. [10] As they did in

the Confederate artillery at Gettysburg, Napoleons constituted 39% of

the Union artillery forces. [11]

Rifled field guns had smaller bores, usually 3 inches

in diameter. These guns were primarily made of cast or wrought iron.

Since the shells were designed to more tightly fit the rifled bore of

the gun at firing, they were accurate at longer distances.

Typical of the rifled artillery piece was the wrought

iron 3" Ordnance Rifle. Capable of throwing an exploding shell over a

mile at an elevation of 5 degrees, it was an effective weapon. 3"

Ordnance Rifles made up 41% of the Federal artillery force at

Gettysburg. [12]

To maximize the power of these guns, 360 in all, the

Union artillery at Gettysburg employed the brigade system. In this

system, each brigade contained from four to six batteries, under the

direct control of the corps artillery chief. A battery consisted of six

guns, ideally all of the same type. The battery was divided into three

two-gun sections. Each gun was provided with its own limber and caisson,

stocked with ammunition. A battery wagon for spare parts also followed

each gun. Five officers and one hundred and fifty enlisted men

maintained and operated this equipment, and 110 horses were provided to

move it. [13]

A gun detachment required nine men to load and fire a

gun, with each cannoneer performing a specific set of functions. [14] Cross-training within artillery units allowed

cannoneers to work a battery with reduced numbers. However, the

specialized nature of artillery duties meant that heavier casualties

could seriously cripple a battery. Units might be forced to cannibalize

gun crews, thus reducing the number of guns available for service. [15] In times of imminent crisis, a battery commander

could recruit infantry volunteers to help fill his depleted ranks. [16]

There had been several moments of imminent crisis

during the fighting on 2 July, and they had taken their toll on the

Federal artillery. Approximately forty batteries with the Army of the

Potomac had been engaged this day, reinforced by fifteen of the nineteen

available Reserve units. [17] From Devil's Den, where

three guns had been taken from Captain James E. Smith's 4th New York

battery, [18] north toward the crest of Cemetery Hill,

it had been an exhausting fight for many artillerists. As Longstreet's

lines had swept to the northeast, batteries had been hurriedly

positioned to fill gaps in the Union position. About 2:30 in the

afternoon, Captain John Bigelow's six 12-pound Napoleons of the 9th

Massachusetts moved from the Reserve to the left to reinforce Major

General Daniel Sickles' threatened Third Corps. Going into position

under fire, they were soon fighting desperately as the Confederates

pressed their attack.

As Captain Bigelow recalled:

Waiting till they (the Confederate infantry) were

breast high, my battery was discharged at them, every gun loaded to the

muzzle with double shotted canister and solid shot,...they were torn and

broken, but still advancing, again gun after gun was fired as fast as

possible and enfilading their line when it could... The enemy opened a

fearful musketry fire, men and horses were falling like hail... The

enemy crowded to the very muzzles of Lieut. Erickson's and Whitaker's

sections, but were blown away by the canister. Sergeant after Sergt. was

struck down,... bullets now came in on all sides for the enemy had

turned my flanks. [M]y men kept up a rapid fire, with their guns each

time loaded to the muzzle.

|

|

A Federal battery readying for action.

|

The 9th Massachusetts battery lost six out of seven

sergeants, a third of its men, and sixty-eight of eighty-eight horses on

the 2nd. It had expended, in addition to its shot and shell, 92 of the

96 rounds of canister it had entered the fight with. Although four of

its guns were taken, they were reclaimed that evening. [19] The battery, however, was shattered.

Another hard-hit unit was Lt. Malbone F. Watson's

Battery I, 5th U. S. Artillery, assigned to the Fifth Corps artillery

brigade of Capt. Augustus P. Martin. Hastily commandeered by "some

unknown officer of the Third Corps", the battery was thrust into the

fight... "without support of any kind." The enemy appeared shortly-say

twenty minutes-after taking position, nearly in front, at a distance of

about 350 yards, and the battery immediately opened upon them with

shell. As they approached nearer, the battery poured in canister, some

twenty rounds, until men and horses were shot down or disabled to such

an extent that the battery was abandoned.

While recaptured later that evening, [20] Battery I and other units had been roughly handled on

the 2nd. Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery's Reserve Artillery Brigade and

Captain John G. Hazard's Second Corps batteries had been shaken and some

reduced to working four guns. [21]

The Artillery had taken losses in officers as well.

Captain George E. Randolph, Chief of Artillery of the Third Corps, and

Capt. Dunbar Ransom of the Regular Reserve had been wounded, commanding

their respective artillery brigades. Captain Charles E. Hazlett, of

Battery D, 5th U.S. Artillery, was killed on the crest of Little Round

Top that afternoon. One other battery commander had been killed, and

eight more wounded. [22] There had also been

considerable losses in material and ammunition. Lieutenant Cornelius

Gillett, ordnance officer of the Artillery Reserve, reported that the

ammunition train of the Artillery Reserve was actively engaged

...supplying ammunition to the batteries of this

corps, and by General Hunt's direction, to those of other corps. On the

evening of the 2nd, I...was kept busy the entire night sending out

wagons and issuing to batteries. [23]

According to Lt. Gillett, the total of rounds issued

to the artillery from the Reserve train numbered 19,189. [24] Interestingly, more of it went to supply the trains

of the Second, Third and Eleventh Corps artillery than to Lt. Col.

McGilvery's Reserve batteries, for whom it was intended. [25] Some of this need was artificial. The Second and

Third Corps, in their rush to arrive on the battlefield, had lost

contact with part or all of their ammunition trains. [26]

In spite of the casualties inflicted on it during the

second day's fighting, the Federal artillery was still a powerful

portion of the Army of the Potomac. While some of this power was

attributable to external factors such as position and number of guns,

much was due to internal changes which magnified its power and

effectiveness on the battlefield. These command and organizational

revisions were the product of two things: bitter battlefield experience,

and the restoration of his command authority in the field to

long-suffering Chief of Artillery Henry Hunt.

Henry Jackson Hunt was a professional artillerist.

Both the son and the grandson of Regular Army officers, Hunt attended

West Point. [27] He graduated on 21 June, 1839,

standing 19th in a class of thirty-one. Members of his class included

such notables as Edward Ord, James B. Ricketts, Isaac Stevens and Henry

W. Halleck. [28] Following graduation, he returned to

Detroit to begin his field service as a member of a heavy-artillery

unit, Co. F of the 2nd U.S. Regiment. [29] Hunt served

in a variety of posts prior to the outbreak of the Mexican-American War,

where he won brevet promotions to Captain and Major. [30]

During the inter-war years, Hunt took up the cause of

improving and professionalizing the artillery service. [31] This was to become his calling - and his life's work.

Artillery had traditionally been viewed as something of a stepchild of

military technology, and never fully appreciated for its potential. Hunt

saw that with proper application and training, artillery might prove a

potent force on the battlefield. He directed much of his efforts,

therefore, toward training officers in the correct uses of the arm. In

the late 1850's, Hunt also served on a board with two other authorities,

William Barry and William H. French, to review and improve current

artillery tactics. [32] The final product of this

revision was completed in March of 1860. Known as Instruction For

Field Artillery, the improvements were the first real changes since

1839. [33] Adopted by the U.S. Army, Confederate

artillerists would follow suit shortly afterward.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Hunt, a moderate

Democrat, was initially assigned the command of the Artillery Reserve of

the Army of the Potomac. On September 28, 1861, he was promoted to

Colonel, and assigned to General George B. McClellan as a staff officer.

Nearly a year later, in September of 1862, he became the Chief of

Artillery in the Army of the Potomac, and a brigadier general. [34] With this promotion came real battlefield authority -

McClellan granted Hunt the power to oversee field dispositions whenever

he felt such supervision was required. Hunt also retained full control

over administration, supply, maintenance and instruction of all

artillery units, active or in the Artillery Reserve of the Army of the

Potomac. [35] Unfortunately for Hunt, this oral

understanding between the two officers was apparently never confirmed

with a written order.

To further cloud matters, on March 26, 1862,

McClellan had issued General Order No. 110, which stated, in part, that:

The duties of the chiefs of artillery and cavalry are exclusively

administrative, and these officers will be attached to the headquarters

of the Army of the Potomac.

The order also directed: They will not exercise

command of the troops of their arms unless specially ordered by the

commanding general, but they will, when practicable, be selected to

communicate the orders of the general to their respective corps. [36]

Following his promotion to Chief of Artillery after

the disastrous Second Manassas campaign, Hunt complained he had much

work to do.

On assuming command, I found the artillery much

disorganized...Major General Porter...ordered that as rapidly as

batteries could be equipped they should be pushed forward, without

regard as to the troops to which they belonged...A number of the

batteries of the Artillery Reserve then became separated from their

command, and attached to troops not only of the Army of the Potomac, but

to those of the Army of Virginia as well...I was compelled to obtain on

the roads the names and conditions of the batteries and the troops to

which they were attached. Not only were the batteries of the Army of the

Potomac dispersed as stated, and serving with other divisions than their

own, but I had no knowledge of the artillery of the corps that had

joined from the other armies than what I could pick up on the road. Many

had not been refitted since the August campaign; some had lost more or

less guns; others were greatly deficient in men and horses, and a number

were wholly unserviceable from all these causes combined. [37]

Following the Maryland campaign, fellow Democrat

McClellan was relieved of command in favor of Major General Ambrose

Burnside. Although stating that he would honor McClellan's verbal

agreement with Hunt regarding the latter's authority in the field, [38] Burnside's attempted tinkering with the artillery was

an omen of things to come. Burnside considered implementing plans to

abolish the Artillery Reserve and to formally subordinate corps

artillery chiefs to infantry commanders. [39] While

Hunt was able to persuade Burnside to put these dubious ideas on hold,

he was not able to convince his commander to change the divisional

deployment of artillery throughout the army. [40]

Under this system, each division was assigned a few batteries, under the

control of the divisional commander. Given the proclivity of division

commanders to jealously husband their own artillery, even at the expense

of more needy comrades nearby, it was a recipe for disaster. It had

nearly proven so at Antietam. [41]

In the aftermath of that battle, Col. Charles

Wainwright, chief of artillery for the First Corps, had presented to

Hunt an improved brigade system of artillery. [42]

This new system attached a larger number of batteries directly to each

corps, under the supervision of the chief of artillery of the corps.

Although Hunt was impressed with the plan, Burnside rejected it. [43] It would take the debacle of Chancellorsville to

revive it.

The battle of Chancellorsville occurred on May 1-5,

1863. As Major General Joseph Hooker now led the Army of the Potomac [44] into battle, the Federal artillery was poorly

organized. The divisional system of artillery dispersion preserved by

Burnside was still in place. Hooker later justified it this way:

In my old brigade and division I found that my men

had learned to regard their batteries with a feeling of devotion, which

I considered contributed greatly to our success. [45]

Whatever success Hooker was referring to did not

include such basics as moving batteries from one division to another.

Just prior to battle Captain James Smith's 4th New York was ordered

transferred from the 2nd Division to the 1st Division of the 3rd Corps.

Smith noted the difficulty of the transfer

This (the transfer) created a very ill feeling on

the part of the men..[T]he Battery had been attached to the Division

longer than any other serving with it, and the men believed they were

being discriminated against and refused to move from the park when

ordered...General [David B.] Birney was notified, and he detailed the

40th New York Volunteers with instructions to move or bury the battery.

Under these circumstances, a transfer was made without further

trouble. [46]

To further complicate matters, Hooker had restricted

his artillery chief to staff functions, and had denied him command

authority in the field. [47] Hooker also presided over

the promotion and reassignment of many artillery officers without

providing replacements for them. The net effect on the artillery service

was to stretch the limits of its command capabilities. At

Chancellorsville, Hunt's artillery contained 412 guns and nearly 10,000

men - with only 5 field-grade officers to direct them. [48]

Given these difficulties, therefore, it is

understandable that the artillery might fail to function properly. On

the third day of battle, Col. Wainwright observed the

disorganization

Batteries had been coming in from the front all

night,...Several artillery officers from the other batteries came up to

me, asking where they could procure ammunition; no one appeared to know

anything, and there was a good deal of confusion...I told him [General

John F. Reynolds] that it seemed to me all the artillery of the army was

running around loose. I had met half a dozen batteries going to the

front, and as many more going to the rear, blocking the road to no

purpose;... [49]

Even when a battery remained in its proper division,

there was no guarantee that an organizational breakdown would not

disrupt things. In the 3rd Corps, Smith's battery was stripped piecemeal

to support other advanced units.

Smith's (Fourth New York) battery was placed in

position near the United States Ford, and much of its material used in

rendering the other batteries of the Second Division immediately

serviceable, preventing its being ordered to the front...It was against

the urgent protests of its officers that it was crippled to render other

batteries that could be of more service able to return at once into

action if called upon. [50]

With this sort of breakdown at hand, someone had to

notify General Hooker. Col. Wainwright approached him and apprised the

general of the situation. The conversation, as remembered by Wainwright,

went something like this:

General Hooker: Well, Wainwright, how is the

artillery getting on?

Self: As badly as it well can. Batteries are being

ordered in every direction, blocking up the roads; and no one seems to

know where to go. Where is General Hunt?

General Hooker: What is the matter?

Self: As near as I can understand, every division

commander wants his own batteries, and battery commanders will obey no

one else's orders. It is just the condition I told you of and wanted to

provide against, by giving artillery officers of rank actual command, so

that they could order any battery. The ammunition trains, too.

General Hooker: Well, we have no time to talk now.

You take hold and make it right.

Self: Where is General Hunt?

General Hooker: At Bank's Ford. You take his

place. [51]

Before accepting this assignment, Wainwright wrangled

from Hooker an admission that the use of the artillery should be

controlled by artillery officers in the field. He also received written

orders temporarily conferring upon him the requisite command authority.

[52] On May 12, 1863, this arrangement was formalized

by General Hooker with the issuance of Special Orders No. 129, which

stated in part that

...a consolidation and reduction of the artillery

attached to the army corps will be effected. The artillery assigned to

each corps will constitute a brigade, under the command of the chief of

artillery of the corps for its command and administration. [53]

Henry Hunt, the man for whom this order was written,

no doubt appreciated the fact that General Hooker had finally realized

the importance of correctly handling the artillery. Nevertheless, he

could not resist one last and final blast toward the man who had helped

to bring about the Chancellorsville disaster.

In his report of the battle, written safely after

Hooker's dismissal, he declared

In justice to the artillery...The command of the

artillery, which I had held under Generals McClellan and Burnside,

...was withdrawn from me when you assumed command of the army, and my

duties made purely administrative, under circumstances very unfavorable

to their efficient performance....As soon as the battle commenced on

Friday morning, I began to receive demands from corps commanders for

more artillery, which I was unable to comply with, except partially, and

at the risk of deranging the plans of other corps commanders...Add to

this that there was no commander of all the artillery until a late

period of the operations, and I doubt if the history of modern armies

can exhibit a parallel instance of such palpable crippling of a great

arm of the service in the very presence of a powerful enemy

[emphasis added]...It is not, therefore, to be wondered at that

confusion and mismanagement ensued, and it is creditable to the

batteries themselves, and to the officers who commanded them, that they

did so well. [54]

After the Chancellorsville defeat, Hunt went about

rebuilding his artillery. As he began to re-equip his decimated

batteries, he requested an extra 1,000 horses for them. [55] He was also concerned about ammunition. Hunt hoped

that this problem would be partially alleviated with the reorganization

of batteries into artillery brigades, each with its own supply train.

However, he knew that the usual tendency of corps commanders on the

march was to neglect their supply trains, including their ammunition

wagons. Hunt also felt that battery commanders frequently expended their

ammunition far too rapidly at the front. Earlier on, he tried to counter

this with orders that forbade a battery from withdrawing from a position

merely because it had exhausted its ammunition supply. Instead, the guns

and the gunners were required to remain in line of battle, possibly

under fire, until the filled caissons returned. [56]

Now the Chief of Artillery was going to try a

different tactic: making sure that more ammunition reached the front

lines. Enlisting the support of the Army Quartermaster Corps, Hunt

created a "secret" ammunition train. [57] Designed to

provide an additional 20 rounds per gun over and beyond the 250 called

for by regulations, this train would help to insure timely access to

ammunition. As Hunt feared infantry interference with this project, he

did not inform Hooker of its existence. When Meade later assumed

command, Hunt kept this from him for a time as well. [58]

To keep this secret, Hunt used devoted artillery

officers who understood the value of artillery organization and supply.

However, many good artillery officers had actively sought their fortunes

in other branches of service, where promotions came more quickly. Among

these were such notables as John Gibbon, author of The Artillerists

Manual, Stephen H. Weed, Alexander Hays, Romeyn B. Ayres, Charles D.

Griffin and William M. Graham. [59] Typically

undergraded for the level of responsibility they bore, the conversion to

the brigade system did not improve the lot of the remaining artillery

officers. No promotions accompanied the reorganization. Commanding the

artillery brigades at Gettysburg were two colonels, one lieutenant

colonel, one major, nine captains and one lieutenant. [60]

Prior to the outbreak of the bombardment, General

Hunt had noted the Confederate artillery deployment along Seminary Ridge

and had correctly surmised its intent. He therefore began to ride along

the line, instructing the corps chiefs of artillery and battery

commanders to withhold return fire for fifteen or twenty minutes after

the Confederate shelling began. He later explained

...it was evident that all the artillery on our

west front, whether of the army corps or the reserve, must concur as a

unit, under the chief of artillery, in the defense...It was of the first

importance to subject the enemy's infantry, from the first moment of

their advance, to such a crossfire of our artillery as would break their

formation, check their impulse, and drive them back, or at least bring

them to our lines in such condition as to make them an easy prey. There

was neither time nor necessity for reporting this to General

Meade.... [61]

Hunt did not have much time. Just as he delivered his

orders to the last battery on the crest of Little Round Top, the

bombardment began. In anticipation of the assault to follow, Hunt

immediately sent orders to Reserve units to be sent up the ridge as soon

as the cannonade ceased.

While in the Reserve area near the Taneytown Road, he

observed the effects of the first enemy salvos -the remains of a dozen

exploded caissons. As he watched many of the Confederate shells

overshoot the crest of Cemetery Ridge and land in the rear of the Union

lines, General Hunt felt that the Confederates were not making the most

of the occasion. Following the surrender of the Army of Northern

Virginia, Hunt encountered a former student, Col. Armistead Lindsay

Long, who had served on Lee's staff during the battle. As Hunt

remembered:

Col. Long...had served in my mounted battery

expressly to receive a course of instruction on field artillery. At

Appomattox...I told him that I was not satisfied with the conduct of

[his] cannonade...,as he had not done justice to his instruction; that

his fire, instead of being concentrated, was scattered over the whole

field. He said, "I remembered my lessons at the time, and when the fire

became so scattered, wondered what you would think about it!" [62]

Other Federal soldiers on the eastern slope of

Cemetery Ridge thought the shelling quite accurate. Of the shells that

landed around General Meade's headquarters on the Taneytown road:

One...burst in the yard amongst the staff horses

tied to the fence, another tore up the steps of the house, another

carried away the supports of the porch, one passed through the door,

another through the garrett, and a solid shot, barely grazing the

commanding general as he stood in the open door-way, buried itself in a

box by the door at his side. [63]

This sudden barrage of concentrated shell-fire

apparently unnerved a staff-officer at headquarters:

One of them, seeing his horse badly wounded by

a piece of shell, rushed into the house for his pistol to put the poor

brute out of pain, and coming output two bullets into a fine, uninjured

horse belonging to Captain [James S.] Hall, Signal officer of the 2d

Corps, and would probably have emptied his revolver as he was a poor

shot, had not Captain Hall interfered. [64]

Finding it impossible to reliably receive and

dispatch communications from the Leister house while the shelling

continued, General Meade and his staff moved into a barn several hundred

yards down the Taneytown Road. Discovering themselves still under fire,

they withdrew to Major General Henry W. Slocum's headquarters on Power's

Hill. [65]

For the infantry soldiers on Cemetery Ridge, who

could not move out of range, the shelling was a difficult experience.

General John Gibbon, an artillerist now commanding the 2nd infantry

division of the 2nd Corps, observed:

The larger round shells could be seen plainly as

in their nearly completed courses they curved in their fall towards the

Taneytown road, but the long rifled shells came with a rush and a scream

and could only be seen in their rapid flight when they "upset" and went

tumbling through the air, creating the uncomfortable impression that, no

matter whether you were in front of the gun from which they came or not,

you were liable to be hit. [66]

Colonel Francis E. Heath of the 19th Maine was on

Cemetery Ridge as his regiment endured the shelling. With a combat

infantryman's gift for understatement, he remembered it this way:

All we had to do while undergoing the shelling was

to chew tobacco, watch caissons explode, and wonder if the next shot

would hit you. On the whole, it was not a happy time. [67]

While the infantry on the ridge was unable to respond

directly to the Confederate bombardment, some of the artillery of

Hazard's and McGilvery's brigades began to return fire to the west. As

Hunt's orders had specifically stated that Federal artillery was not to

immediately respond to the Confederates, Col. Alexander later felt

that:

...we must have made it pretty hot for the

opposite line from the word go, for General Hunt's orders not to reply

for 15 or 20 minutes, I am very sorry to say, were immediately

forgotten. I hope that he court-martialed every rascal of them for it

afterward; for how much more all of us Confederates might have enjoyed

that 15 minutes. But, instead of giving us a beautiful exhibition of

discipline his whole line from Cemetery Hill to Round Top seemed in five

minutes to be emulating a volcano in eruption. Lots of guns developed

which I had not before been able to see, & instead of saving

ammunition, they were surely trying themselves to see how much they

could consume. [68]

One of the places that Confederate shells had made

"pretty hot" was the crest of Cemetery Hill itself. The objects of their

attention were some Reserve guns and the five batteries of the 11th

Corps artillery brigade under Major Thomas Osborn.

A native of New Jersey, Thomas Ward Osborn attended

Madison [now Colgate] University and was admitted to the New York bar in

1861. Later that same year, he accepted an officer's commission and

became a lieutenant in Battery D, New York Light Artillery. A veteran of

the Peninsula campaign and the battles of Fredricksburg and

Chancellorsville, [69] Osborn had recently been made

chief of the 11th Corps artillery. Previously a brigade commander with

the Reserve artillery, Osborn had been reassigned by Hunt to the 11th

Corps because, in Hunt's view, "...the batteries were worthless, and

a disciplinarian and an industrious officer was required."

During the period before Gettysburg, Osborn refitted

the batteries and instituted regular artillery drills. He reorganized

the brigade staff, and felt that "...by close attention and constant

watching I can soon get them into fair condition and fit for the

field." [70] His efforts produced results. The

11th Corps Artillery at Gettysburg was a far cry from the broken and

disorganized outfit that had clogged the roads at Chancellorsville.

After covering the withdrawal of the 11th Corps on

July 1, Osborn's guns took position atop Cemetery Hill. There they had

remained, commanding its eastern, northern and western approaches. Now,

as the bombardment heated up, something of a cross-fire began to play on

the batteries on the hill. Osborn noted of the fire from the west

that

Their range...was perfect, but...the elevation

[was] about twenty feet above our heads.. Indeed, if the enemy had been

as successful in securing our elevation as they did the range there

would not have been a live thing on that hill fifteen minutes after they

opened fire. [71]

|

|

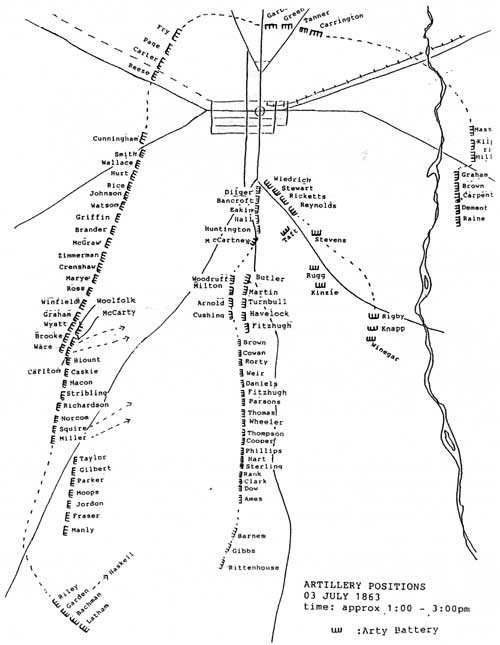

Artillery Positions, 03 July 1863 time:

approx 1:00 - 3:00pm (click on image for a PDF version)

|

From the east side of Cemetery Hill, the Confederates

soon made things hotter for the Federal gunners. On Benner's Hill, over

a mile from Osborn's guns, the 20 lbr Parrotts of Captain John

Milledge's Georgia Regular Artillery [72] began to

fire:

....[S]everal guns, two batteries or more, began

to open on us from the ridge beyond East Cemetery Hill...These last guns

opened directly on the right flank of my line of batteries. The gunners

got our range at almost the first shot...they caught us square in the

flank, and with elevation perfect. It was admirable shooting. They raked

the whole line of batteries, killed and wounded the men and horses and

blew up the caissons rapidly. I saw one shell go through six horses

standing broadside. [73]

Despite the accuracy of this fire, Osborn reacted

quickly. He turned the guns of Captain Elijah Taft's 5th New York and

one other Reserve battery [74] against the

Confederates. Taft's guns were 20 pounders as well, and they soon

improved the situation on Cemetery Hill. Osborn related, "...in a few

minutes we so demoralized them that they lost the elevation but not the

direction, and they too fired high. As it was, we suffered

severely."

In the midst of this fire, news was brought to Osborn

that, in his words, "roused my temper considerably." It had been

reported that a Reserve battery the Major requisitioned was behaving

badly. As he wrote years later:

The battery had been under fire but a few minutes

when word was brought to me that the men were throwing ammunition out of

the [limber] chests into [some] timber. This was in order to get clear

of it and then represent that it was expended and so retire from the

field. I went to the battery, gave the captain some orders in emphatic

English and then left him. A few minutes later several of the men called

out, "Look, Major, see the cowards." I did look and saw that Ohio

battery with all the men mounted on the ammunition chests going full

speed...down the Baltimore Pike. I never saw that battery again, and as

it did not belong to my command, I did not report it to its proper

superiors. Doubtless, the captain reported to the commander of the

Reserve Artillery that he was in the hottest of the fight and that he

and all his men were heroes. At all events, the giant monument on

Cemetery Hill stands today to the credit of that battery. [75]

Osborn was mistaken. Although Captain William

McCartney's 1st Massachusetts Battery did report finding 48 rounds of

3-inch projectiles that had apparently been "dumped" [76] on Cemetery Hill, Osborn, in his account,

misidentified the unit and their motive. Captain McCartney stated he was

ordered into position to "relieve the 1st New Hampshire Battery, said

to have been out of ammunition." [77] That

battery, commanded by Captain Frederick M. Edgell, a Mexican-War

veteran, [78] had been plagued with ammunition

trouble. In his report, Capt. Edgell noted that, "...the Schenkel

combination case [shot] seldom exploded. From what experience I have had

with this fuse, I think it is not reliable." [79]

Edgell's experience was verified later in tests that confirmed that the

fuse in question was good only 55% of the time. [80]

Roughly one of every two shells exploded.

Under the pressure of an intense cross-fire, such as

that which was encountered on Cemetery Hill, it is conceivable that the

gunners threw out ammunition found defective and concentrated on using

other shell types that worked. As no charges were lodged against Edgell

regarding this incident, it is logical to assume that the "dumping" was

more a product of bad ammunition than any cowardice under fire.

Defective ammunition surfaced in other batteries as

well. Captain Hubert Dilger, commanding Battery I, 1st Ohio Light

Artillery, complained in his report to Major Osborn that:

I was completely dissatisfied with the...fuzes for

12 pounder shells and spherical case, on the explosion of which, by the

most careful preparation, you cannot depend. The shell fuzes, again,

were remarkably less reliable than those for spherical case. The fuzes

for 3-inch ammunition caused a great many explosions in our right before

the mouth of the guns, and it becomes very dangerous for another battery

to advance in the fire of his batteries, which kind of advancing of

smooth-bore batteries is of very great importance on the battlefield,

and should be done without danger. I would, therefore, most respectfully

recommend the use of percussion shells only. [81]

As Captain Dilger's report suggests, faulty

ammunition and fuzes were not just inconvenient; they could be deadly as

well. Further down the artillery line stood the batteries of Captain

John G. Hazard's 2nd Corps Artillery brigade. One of these, Captain

James McKay Rorty's Battery B, 1st New York, was posted a few rods south

of the Angle, busily engaging targets to the northwest. As the gunners

sent shells over the heads of the Federal infantry posted about fifteen

feet in front of them, a shell from one of Rorty's Parrotts burst

prematurely, cutting down Lt. Henry Ropes of the 20th Massachusetts.

Ropes had been reading to his men from a volume of Charles Dickens, [82] helping to steady them during the fierce bombardment.

To spare the infantry any more "friendly-fire" casualties, Rorty moved

his battery forward. [83]

Rorty's commander, Captain John G. Hazard, was a

Rhode Islander who had begun his artillery career as a First Lieutenant

in a volunteer battery. Commissioned in the summer of 1861, he was

promoted to command Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Artillery shortly before

the battle of Second Manassas. In the reorganization of the artillery

after Chancellorsville, he was appointed to the position of Chief of

Artillery for the Second Corps. [84] His batteries saw

action on 2 July, and they took some casualties. [85]

On the third, Hazard's brigade contained 26 guns, dispersed among five

batteries. [86] North of Rorty's four rifles were the

Napoleons of First Lieutenant T. Fred Browns Battery B, 1st Rhode Island

Artillery. [87] Now commanded by First Lieutenant

William S. Perrin, this battery fielded four guns, having sent two to

the rear at the close of the fighting on July 2. [88]

In the Angle area itself were six 3-inch rifles of

Lieutenant Alonzo Hersford Cushing's Battery A, 4th U. S. Regular

Artillery. Six more 3-inch rifles of Battery A, 1st Rhode Island

Artillery were posted just to the north of the Angle, under the command

of Captain William A. Arnold. On the right flank of the artillery

brigade, in the area of Ziegler's Grove, was Battery I, 1st U. S.

Regular Artillery. Commanded by Lieutenant George A. Woodruff, the

battery possessed six 3-inch rifles.

Of the five batteries in Hazard's brigade, two were

commanded by professional soldiers. Lieutenants Cushing and Woodruff

were both members of the West Point class of 1861. Woodruff hailed from

Michigan, Cushing from Wisconsin. [89] These

northwestern men would see much action this day, and both would prove

their worth in the afternoon struggle. The other three units were led by

experienced volunteer soldiers. [90] These volunteer

batterymen of Hazard's brigade, along with their Regular counterparts,

would find themselves in the very center of the storm of Confederate

shells that afternoon.

The Regular batteries of the brigade had spent an

active morning. Around 8:00, Confederate artillery opened fire on

Cushing's battery and detonated three limbers in rapid succession. [91] Woodruff's guns responded, and during the course of

the morning engaged the enemy's artillery eight different times. [92]

Due in part to the shelling of the morning hours,

Confederate gunners had the range and the elevation of Hazard's

batteries as the afternoon bombardment began. As the fire began to focus

on Cushing's guns, General Gibbon observed that: Suddenly, with a

shriek, came a shell right under the limber-box, and the poor gunner

went hopping to the rear on one leg, the shreds of the other dangling

about as he went.

Gibbon was still nearby when the Confederates

replicated their morning's achievement:

I had made but a few steps when three of Cushing's

limber boxes blew up at once, sending the contents in a vast column of

dense smoke high in the air, and above the din could be heard the

triumphant yells of the enemy as he recognized this result of his

fire. [93]

The accuracy of the Confederate shells at this point

made the fight intense around Cushing's guns. Under such circumstances,

an officer's commanding presence can be an invaluable asset. One of the

batterymen, Christopher Smith, recalled an incident that highlighted

these qualities in Lieut. Cushing:

The fire that we were under was something

frightful and such as we had never experienced before...Every few

seconds a shot or shell would strike right in among our guns, but we

could not stop for anything. We could not even close our eyes when death

seemed to be coming. After the firing had been going on about 15

minutes, a shot struck No. 3 gun -I remember it well- and tore away one

wheel. In the terrible excitement the gunners of No. 3 got

panic-stricken and started to run just as soon as they saw their gun was

dismounted. There is always an extra wheel with the caisson, but the men

in their fright had forgotten this. Lieut. Cushing had not. Seeing the

men run, he drew his revolver and called out, "Sergt. Watson, come back

to your post. The first man who leaves his gun again I'll blow his

brains out!" In two minutes No. 3 was thundering away again as hot as

ever. [94]

But Lt. Cushing knew that his men were taking

terrible punishment and endeavored to find targets along the Confederate

line for his guns. Spying a group of Confederate officers under a clump

of trees, Cushing directed his cannoneers to fire on them. The first

shot was high, but the second shot "...struck in their midst and they

scattered at a lively rate." [95]

To the north of Cushing's battery, in the area of

Ziegler's Grove, Lt. Woodruff and the men of Battery I were having a

difficult time as well. In support of Woodruff's guns stood the 108th

New York infantry. Assistant Surgeon Francis Moses Wafer of the 108th

watched as the cannoneers returned fire:

Our artillerymen sprang to their posts at once and

replied with more than their usual pluck and spirit but it soon became

evident that they were being [rapidly] overpowered, worsted and fairly

battered out of [sight]. I could plainly see their caissons being

frequently blown up, although the explosions of these could not be heard

in the general crash yet the sudden bursting up of fleecy clouds

invariably told the story. The horses rolled in heaps everywhere tangled

in their harness with their dying struggles - wheels knocked off, guns

capsized and artillerists going to the rear or lying on the ground

bleeding in every direction. [96]

As the smoke from the assembled batteries began to

obscure targets on the Confederate line, Hazard's gunners adjusted the

elevation on their guns and continued firing into the thickening mist.

The only targets now were the murky red flashes of Confederate guns,

dimly visible in the smoky fog. Nonetheless, the batteries of the Second

Corps continued to shell an enemy they largely could not see.

This, however, was exactly what Henry Hunt did

not want to happen. His orders to his artillery commanders, given

just before the bombardment began, had specifically enjoined his gunners

not to return fire, "... for fifteen or twenty minutes at

least". If suitable targets were discovered after that time

period, the gunners were to resume firing "...slowly, deliberately,

and making target practice of it." [97] The

cross-fire of artillery that Hunt wanted to deliver on the enemy's

infantry would require the gunners to have sufficient quantities of

long-range projectiles on hand as the attack began. Hunt felt that none

of it should be wasted in an essentially useless

counter-bombardment.

Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, commander of

the U.S. Second Corps, disagreed. [98] Hancock readily

appreciated the psychological impact that the bombardment had upon his

troops. He felt the proper role for the Union artillery during the

cannonade was to respond to it immediately, with force. Brevet Brigadier

General Francis Walker, Chief of Staff for the Second Corps, later

echoed his commander's view on this matter, writing:

Would the advantage so obtained have compensated

for the loss of morale in the infantry which might have resulted from

allowing them to be scourged, at will, by the hostile artillery? Every

soldier knows how trying and often demoralizing it is to endure

artillery fire without reply. [99]

Hancock therefore countermanded General Hunt's

instructions to Hazard and had ordered Hazard's batteries to open fire.

Captain Hazard, placed in a difficult position, chose not to dispute

Hancock's orders. This would have serious consequences later in the

afternoon.

The dispute between the two generals did not strictly

center on how to reply to the Confederate artillery. It also concerned

command authority. Was General Hunt, Chief of the Artillery of the Army

of the Potomac, a de facto corps commander, commanding all the artillery

of the army? Or was he a glorified staff officer, subordinate to the

line authority of the infantry corps commanders? It was a difficult

question, not easily answered. The debate over which view was correct

would resonate for years. [100]

With the guns of Hazard's brigade blazing away,

Hancock turned his attention to the 39 guns of Lt. Col. Freeman

McGilvery's 1st Volunteer Reserve Artillery Brigade. [101] These guns were positioned to the south of the

Second Corps line, stretching from north of the George Weikert farm

toward the left of Hazard's brigade. Like Hazard's, McGilvery's units

had received orders from Hunt to conserve their ammunition at the start

of the bombardment. These guns, in contrast to Hazard's battered

batteries, were not under the concentrated volume of fire that the

Second Corps guns were. As one artilleryman put it, "The Rebels were

not doing us any harm..." [102]

General Hancock rode to McGilvery's position and

directed three batteries on the brigade's right flank to open fire. [103] These batteries were Captain Patrick Hart's 15th

New York Independent, with four Napoleons, Captain Charles Phillips'

Fifth Massachusetts Battery E, with six 3-inch rifles, and Thompson's

Battery, F and C consolidated Pennsylvania Artillery, which contained

five 3-inch rifles. McGilvery declined to fire, stating that his own

commander (Hunt) had instructed when the batteries should open. General

Hancock responded that "my troops cannot stand this cannonade and

will not stand it if it is not replied to." [104]

Having obtained little satisfaction from McGilvery,

Hancock then moved on to the 15th New York Battery. In command of its

four Napoleons was Captain Patrick Hart, an Irish-born soldier with

seventeen years of Regular Army experience and a somewhat irritating

personality. John N. Craig, on Hunt's staff, noted of Hart that: It

was exactly his way to be riding about in the manner most likely to

attract the attention of anyone swelling for someone to swear at.

[105]

Given Hancock's frustration with the artillery that

afternoon, the meeting between the two men must have been something.

Hart recalled of the encounter:

...[S]ome considerable time after the enemy opened

fire General Hancock rode up to me and in not a very mild manner

[emphasis added] wanted to know why I had not opened fire. I informed

him that I had received my orders from General Hunt Chief of Arty and I

would obey them. He ordered me to open fire that I was in his line. I

replyed that should he give me a written order that I would open fire

under protest. [106]

Captain Charles Phillips, commanding the 5th

Massachusetts, had a similar experience. He too was ordered to open fire

by Hancock, in his words, "...[T]hereby showing how little an

infantry officer knows about artillery." [107]

For a short while these batteries returned the Confederate fire. After a

few rounds had been fired, however, McGilvery ordered the firing to

cease. [108] When the Confederate infantry appeared,

McGilvery's guns would be ready.

South of McGilvery's line, on the crest of Little

Round Top, were positioned the six 3-inch guns of Battery D, 5th U. S.

Artillery. Commanded by Lieutenant Benjamin F. Rittenhouse, these guns

marked the end of the Federal artillery line. [109]

During the early portion of the bombardment, this battery took some

slight casualties from the advanced Confederate guns in the Peach

Orchard area. [110] The main focus of the Confederate

artillery, however, remained Cemetery Ridge and the Union center.

Hazard's guns continued to suffer the effects of a

heavy and accurate fire. In Battery "B", 1st Rhode Island Artillery, the

men struggled to keep up a return fire as more Confederate shells found

their mark. One of them struck the muzzle of the fourth piece and

instantly exploded, killing two cannoneers who were attempting to load

it. [111] Corporal J. M. Dye, on detached service

from the 140th Pennsylvania infantry, was serving as the gunner. He

recalled what happened next:

Billy Jones and old Mr. Gardner were killed, and

my No. 3 wounded, and went to the rear; my No. 4 was played out and on

the ground. I tried to get him up to thumb [the] vent, while the

sergeant and myself tried to load the gun. But he wouldn't budge, so I

got a stone and, tearing a piece off my shirt laid it on the vent. I

then went and held the shot in place, which the sergeant had placed in

the gun, while he swung on with the rammer. I had to hold the shot in on

account of a dent in the muzzle, made by the Rebs' shell that killed

Jones and Gardner, and we could not get it in. Someone came with an axe,

and as they were going to make a strike with it, a rebel shell struck

the cheek and exploded knocking out a spoke; this raised the gun up on

one wheel, but did not dismount it, but it settled back. This put a stop

in trying to load it; the gun, in cooling, had clamped on to the shot,

so that we could not get it out again, and the gun went to the rear with

the shot in the muzzle. [112]

To the north, in Cushing's battery, Confederate fire

also produced dramatic moments. A shell passed through a horse, then

entered and exploded inside another. One fragment exited the horse and

struck a teamster, partially disemboweling him. Previously wounded at

Fair Oaks, he had often stated that if he was ever again seriously

wounded, he would rather be shot than endure the pain. Now he begged his

comrades to put him out of his misery. Christopher Smith remembered:

We could do nothing for him and of course none of

us felt like shooting him as he begged us to do. Finally he got his

revolver out of his belt, and saying good-bye boys, turned the muzzle to

his head and blew his brains out. [113]

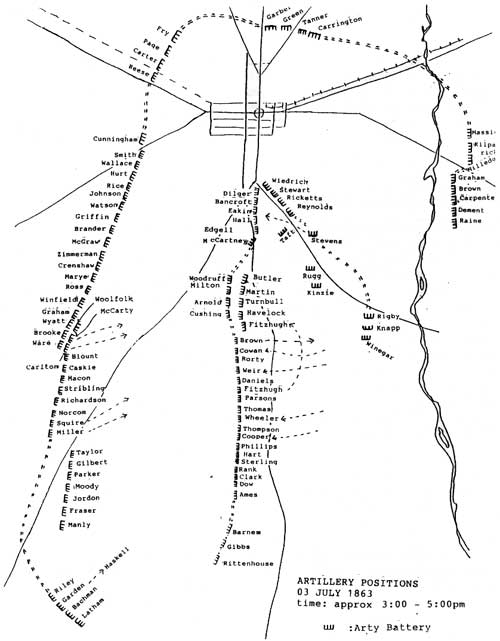

|

|

Artillery positions 03 July 1863 time: approx 3:00 - 5:00pm (click on image for a PDF

version)

|

The men also had to contend with "secondary" types of

shrapnel. One soldier noted that the air was alive with "fragments of

rocks flying through the air shattered from a stone fence in front of

Battery A." [114]

Woodruff's gunners were also feeling the heat.

Surgeon Moses Wafer of the 108th noted that:

The few large oaks that hung over Woodruff[s]

battery were torn in splinters, their limbs dropping in some cases on

men of the 108th. Several batteries had concentrated their fire on this

battery in order to silence it, but although nearly all the horses were

destroyed and one gun of the six dismounted, yet the gallant commander

fought them until he had not a round of ammunition left except a few

rounds of canister shot... [115]

Cushing's battery was down to only two guns and a few

rounds of canister as well. [116] General Hunt's

concern about premature exhaustion of ammunition was being borne out. Up

and down Hazard's front, long-range ammunition was growing scarce.

The cannonade was now extending into its second hour.

By this time a number of senior commanders - Generals Meade, Howard,

Hunt, and Major Osborn - had come to the conclusion that the

Confederates might be induced to bring on their assault if the Federal

artillery fire was halted. General Howard, Major Osborn and General Hunt

met on Cemetery Hill to discuss the possibility of doing so. Hunt

stated, "General Meade had expressed a hope that the enemy would

attack, and he had no fear of the result." Osborn asked Hunt to go

see General Meade to get permission to cease fire. Perhaps with the

ghost of Chancellorsville dancing in his head, Hunt, "with an

expression of anxiety", asked the Major if he could control his men

under such a heavy fire if the order to cease was given. Osborn assured

him that there was nothing to fear from the order. Hunt then conferred

for a few moments with General Howard and announced that he would issue

the order at once himself. Invoking his powers as Chief of the

Artillery, Hunt commanded the Federal batteries to cease firing. [117] He then rode out to pass the order down the line.

As he moved off the hill, toward the batteries on Osborn's left, he was

approached by a staff officer bearing orders from General Meade to that

same effect. [118]

The decision to stop the return fire helped to

convince the Confederates that the bombardment had been sufficient.

Initially, the infantry attack was to have followed a short but intense

shelling of the Union position. Col. Alexander noted:

Before the cannonade opened, I had made up my mind

to give Pickett the order to advance within fifteen or twenty minutes

after it began. But when I looked at the full development of the enemy's

batteries...I could not bring myself to give the word. It seemed madness

to launch infantry into that fire, with nearly three-quarters of a mile

to go at midday under a July sun. I let the 15 minutes pass, and 20, and

25, hoping vainly for something to turn up.

As the Confederate fire continued, Alexander became

concerned about his available ammunition supply. After waiting the

twenty-five minutes, he sent a note to General Pickett, asking him to

"come at once, or I cannot give you proper support." Five minutes

after sending the note, Alexander noted that the Federals' fire was

slackening. He also observed batteries in the "cemetery" [probably the

Angle] limbering up and apparently leaving the field.

This gave him some cause for cautious optimism, as he

stated later:

We Confederates often did such things as that to

save our ammunition for use against infantry, but I had never before

seen the Federals withdraw their guns simply to save them up for the

infantry fight. So I said, "If he does not run fresh batteries in there

in five minutes, this is our fight." I looked anxiously with my glass,

and the five minutes passed without a sign of life on the deserted

position, still swept by our fire, and littered with dead men and horses

and fragments of disabled carriages. [119]

Alexander's optimism was misplaced. While some of the

batteries in Hazard's line had sustained serious damage, Reserve units

were nearby and prepared to replace them. [120]

Osborn's gunners on Cemetery Hill had also taken some casualties, but

the batteries still functioned. The guns of McGilvery's line were only

slightly damaged. Taken as a whole, the Union artillery line was intact

and prepared for the Confederate infantry.

General James Longstreet, commander of the First

Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, did not want to make the

infantry attack. Now, as Pickett's division began to move toward the

front, Alexander told Longstreet he feared he would not have sufficient

stocks of ammunition to properly support the assaulting infantry troops

as they advanced. General Longstreet turned to Alexander and instructed

him to "Stop Pickett immediately and replenish your ammunition."

Alexander replied that it would take too long, and the enemy would be

able to recover from the effect of the previous fire. Longstreet then

responded, "I don't want to make this attack. I would stop it now but

that General Lee ordered it and expects it to go on. I don't see how it

can succeed."

Alexander listened, but: ...did not dare offer a

word. The battle was lost if we stopped. Ammunition was far too low to

try anything else, for we had been fighting three days. There was a

chance, and it was not my part to interfere. [121]

With nothing to delay them further, the Confederate

infantry began to advance out of the woods into the clear. Almost

immediately thereafter, the Federal guns opened upon them. [122] The batteries in McGilvery's line, and

Rittenhouse's Battery "D", 5th U.S. Artillery, posted on Little Round

Top, were well-positioned to hit the Confederates as they appeared.

Captain Phillips of the 5th Massachusetts recalled.

As soon as the rebel line appeared, our cannoneers

sprang to their guns, and our silenced batteries poured in a rain of

shot and shell, which must have sickened the rebels of their work. I

never saw artillery so ably handled, or productive of such decisive

results. It was far superior even to Malvern Hill. [123]

Captain Hart of the 15th New York Battery, posted to

the left of Phillips' guns, fired into the right flank of the line. He

observed:

When the great charge came the right, of which

would have overlapped my battery, I opened on the right of the enemies

line and forced them to incline their left which gave me a infalading

fire on their line. [124]

The First Pennsylvania Artillery, Batteries "C" and

"F" Consolidated, also under McGilvery, was posted to the north of

Phillips' and Harts' guns. From their position, they did good execution

on the advancing infantry. Sergeant Joseph B. Todd remembered:

On they came whooping and yelling on double quick

time their artillery playing on us all the time. When within about 300

yards of us we got the word to fire... We mowed them down like ripe

grain before the cradle. They could not advance under our galling fire

and began to recoil. [125]

From his lofty perch, Lieutenant Rittenhouse and his

Regular guns were also able to effectively assist McGilvery's units as

they smote the Confederate flank. He too opened upon Pickett's men as

they advanced and delivered an oblique fire. As the Confederate lines

moved closer, however, the limited space of the hill restricted him to

using only his right section. These guns were manned by two Irishmen,

Lt. Peeples and Sgt. Grady, who, in the words of Lieutenant Rittenhouse,

"would rather fight than eat." Rittenhouse remembered that these

"splendid shots"

...tried to make up for the loss of fire from the

other guns. Many times a single percussion shell would cut out several

files and then explode in their ranks, several times almost a company

would disappear, as a shell would rip from right to left among them.

Every shot pointed by these two men, seemed to go where it was

intended. [126]

The Federal fire was effectively hammering the

Confederate infantry. From their positions, the batteries of McGilvery's

line continued to blast away at Pickett's men and the infantry supports

that followed.

Captain Hart reported: ...[The] second line

appeared to be coming direct for my battery. I turned all my guns on

this line, every piece loaded with two canisters. I continued this

dreadful fire on this line until there was not a man of them to be

seen. [127]

In the rear of the line, Col. Alexander had inspected

the ammunition supply of his guns, and ordered those with roughly

fifteen rounds of long-range projectiles to follow the infantry and

support it.

While leading this impromptu battery forward, he

encountered a casualty of Kemper's command:

We were halted for a moment by a fence, and as the

men threw it down for the guns to pass, I saw in one of the corners a

man sitting down and looking up at me. A solid shot had carried away

both jaws and his tongue. I noticed the powder smut from the shot on the

white skin around the wound. He sat up and looked at me steadily, and I

looked at him until the guns could pass, but nothing, of course, could

be done for him. [128]

Nothing could be done for the rapidly increasing

number of other wounded Confederates, either. The unwounded ones,

however, could do something. They began to drift to their left, toward

the guns of Hazard's brigade and the Second Corps line. Captain Hart

observed: During all this time [the] Hancock Arty was as silant as

the grave. They had exhausted all their ammunition and were ready to

lumber to the rear. [129]

General Hunt, after locating and ordering up the

Reserve batteries, took position near the center to watch the results.

He was disappointed with what he saw. He wrote later

to my great surprise and chagrin, for I never

saw a finer opportunity to display the power of the arm, (emphasis

added) Hazard's guns were silent and the heavy crossfire relied upon to

drive the enemy back, or throw his troops into disorder and so deliver

them a comparatively easy prey to our infantry, was not obtained. We had

between 70 and 80 guns, nearly equally divided into two masses, the

crossfire of which would have added more than one half to the value of

their combined direct fire, so that the effective power of our artillery

defence was reduced by Hazard's silence to less than a third of what it

ought to have been. But it was too late to rectify this... [130]

The Confederates continued to close the distance to

Cemetery Ridge and the Second Corps batteries. They were now close to

canister range. As Lieutenant Perrin and Captain Arnold prepared to

withdraw what was left of their shattered Rhode Island batteries out of

the line, some of the attacking infantry began moving toward Captain

Rorty's battery, on the left of the brigade. Now reduced to one workable

gun, the battery had also taken many casualties, losing by one account

fifty-six men in half an hour. [131] With the

Confederates closing in, Rorty needed to work his gun. Volunteers were

detached from the nearby 19th Massachusetts infantry and hastily pressed

into service. [132] No time could be spared for

anything beyond the most rudimentary instruction; the enemy was too

close. The novice artillerists took their positions and began to work

the gun.

To the north of Rorty's gun, Captain Andrew Cowan's

First New York Independent Battery moved in to replace Petit's battery.

When the bombardment began, that battery had been positioned to the

south of Hazard's brigade. As the smoke lifted, Cowan was ordered to

report to General Webb. Cowan remembered

I saw an officer standing near the clump of trees,

waving his hat at me, and I saw that a battery at the left of the trees

was withdrawing. The officer was General Webb and the battery was

Brown's B, First Rhode Island, disabled and out of ammunition. [133]

The battery moved in at a gallop to fill the vacated

space. In the rush to move into position, the sixth piece advanced to

the north of the clump of trees and came into battery close on Cushing's

left. Captain Cowan recalled, "At this moment Pickett's troops were

seen forming for the assault, and we lost no time in getting our shell

among them." [134]

Cowan's battery moved in as the guns of William

Arnold's Battery A, 1st Rhode Island, began to withdraw from the line.

They had almost completely exhausted their ammunition supply, and

messengers were unable to locate Captain Hazard or Lieutenant Gamaliel

Dwight, the Corps ordnance officer, to obtain more. General Hunt was

informed of the situation, and he issued a written order moving a

battery from the Reserves to replace it. [135] The

entire battery, however, appears not to have withdrawn at the same time.

A member of the 14th Connecticut infantry, posted just to the right of

the battery, observed that "One or two pieces which had been pushed

out further to the front were left behind." When the other guns

moved back to the rear, the 14th extended its left to cover the open

position. [136]

To the north, in Woodruff's battery, Lt. Tully McCrea

was momentarily overwhelmed when first he saw the Confederate advance.

Many years later he wrote, "...I thought our chances for Kingdom

Come, or Libby Prison were very good." McCrea, a member of the West

Point class of 1862, quickly recovered and as the Confederates

approached, observed:

Never was there such a splendid target for Light

Artillery... We with the smoothbores, loaded with canister and bided our

time.... When the enemy's Artillery fire ceased and we saw his Infantry

preparing to charge our position, Woodruff had his guns run to the crest

of the hill, and gave the necessary orders to prepare for the struggle

which was coming. He would not fire a shot until the enemy got in close

range where our canister would be effective. [137]

The left section of the battery was run up and

obliqued to the southwest as the enemy moved forward, to catch the

exposed Confederates in the flank. Lieutenant McCrea wrote:

At the command "Commence firing" everybody worked

with a will and two rounds of cannister per minute was delivered from

each gun. The slaughter was fearful, and great gaps were made in the

mass of the enemy upon each discharge. [138]

Down the line, the infantrymen-turned-artillerists of

Rorty's battery clustered around their remaining rifle. As Confederates

of General James Lawton Kemper's brigade gained ground toward the gun,

the improvised cannoneers attempted to stop them. Loading the gun with a

triple charge of canister, which probably included three powder charges

as well, the piece was discharged. The force of the blast overturned the

gun in its recoil, "but deal[t] death amid the opposing ranks."

[139]

To the left of Rorty, the four 3-inch rifles of

Lieutenant William Wheeler's 13th New York Battery moved into position.

Assigned to the 11th Corps Artillery Brigade of Major Thomas Osborn, the

battery had been in reserve behind Cemetery Hill. Receiving orders from

Osborn to assist the Second Corps, Wheeler was directed by General

Hancock to come into line above the head of Plum Run. He later

reported:

Upon coming into battery, I found the enemy not

more than 400 yards off, marching in heavy column by a flank to attack

Petit's battery, which was on my right and somewhat in advance of me.

This gave me a fine opportunity to enfilade their column with canister,

which threw them into great disorder, and brought them to a halt three

times. [140]

To the north, the men of Cushing's battery were also

preparing for close quarters. Christopher Smith stated:

We had now only two guns and four rounds of

ammunition... We saw the Johnnies coming out towards us and knew there

was no time to lose. The two pieces were still about 150 feet back from

the stone wall...So we run the pieces down to the wall and I remember

taking out a stone so that the muzzle of the gun protruded just over the

top of the wall. [141]

Lieutenant Cushing moved forward with his pieces.

With the Confederate infantry still some 450 yards distant, he ordered

that the remaining canister be brought up close to the guns. As this was

done, he was hit by a Minie ball in the right shoulder. A few seconds

later, he received a painful wound in the testicles. Cushing instructed

Sergeant Fuger of the battery to stay close and repeat his commands to

the battery. Fuger saw the severity of his commander's wounds and

suggested that he move to a safer location in the rear. "No," he

replied firmly. "I stay right here and fight it out or die in the

attempt." He would soon be given that opportunity. Shortly

afterwards, at his guns, Cushing was shot in the mouth and died

instantly. [142]

With their lieutenant down, the battery continued its

work. Christopher Smith claimed that the Confederates did not see the

muzzles of the two rifles until they were close in:

As soon as they saw the muzzles of the pieces the

poor wretches knew what it meant - it meant death within the next three

seconds to many of them, and they knew it. I remembered distinctly that

they pulled their caps down over their eyes and bowed their heads as men

do in walking against a hail storm. They knew what was coming. [143]

Near the battery were the soldiers of the 69th and

71st Pennsylvania infantry. Although some of these soldiers stepped up

to assist the cannoneers, one infantryman noted how the artillery and

infantry did not mix well at the wall. Anthony McDermott of the 69th PA

recalled of the guns:

These pieces done more harm in that position to us

than they did the enemy, as they only fired two or three rounds when

their ammunition gave out, and one of those rounds blew the heads off

two privates of the company, who were on one knee, at the time, besides

these pieces drew upon us more than our share of fire from the battery

that followed Pickett from the woods opposite to us, the gunners left us

leaving their guns behind, hence they were useless. [144]

The long-range shelling from Alexander's battery

noted by McDermott was also remarked upon by Major Edmund Rice of the

19th Massachusetts, who later wrote:

A Confederate battery near the Peach Orchard

commenced firing, probably at the sight of [our] men leaving their line

and closing to the right upon Pickett's column. A cannon-shot tore a

horrible passage through a dense crowd of men in blue, who were

gathering outside the trees; instantly another shot followed and fairly

cut a road through the mass. [145]

The fire from the Union guns, however, remained

focused on the attackers. One of Cushing's pieces was pressed into

service even after it had fired its last round of canister and was