|

"ANDREW ATKINSON HUMPHREYS"

Divisional Command in the Army of the Potomac

Kavin Coughenour

"Division — a major administrative and

tactical unit/formation which combines in itself the necessary arms and

services required for sustained combat, larger than a regiment/brigade

and smaller than a corps." [1]

Throughout history, the way armies around the world

designed and organized their forces determined in great measure how they

waged battles and campaigns. The modern United States Army definition of

a division quoted above describes the essence of the divisional

formations organized for combat during the American Civil War.

During the first three days of July 1863 at the

battle of Gettysburg, the Federal Army of the Potomac deployed nineteen

infantry divisions into combat against the nine infantry divisions of

the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. By the time of the American

Civil War, the division had evolved into a very powerful combat

formation in most European armies. How did divisional combat formations

evolve throughout world military history? How were divisions organized

and operated during the American Civil War? Finally, how did the Civil

War division function within the command and control structures of the

time? This paper explores these questions through an examination of the

combat record of Maj. Gen. Andrew Atkinson Humphreys, commander of two

divisions in the Army of the Potomac during the war.

In European armies during the early part of the

eighteenth century, the term "division" was used to describe a portion

of a battalion. That part of a battalion constituting a "division"

varied among the European armies during the early eighteenth century.

Generally, battalions made up of four or eight companies were divided

into four "divisions" and battalions made up of six companies were

divided into three "divisions." For example, in 1749 a standard

infantrie francaise battalion consisting of twelve fusilier

companies and one grenadier company was divided into six divisions. In

the 1750s the term "division" in the French army would take on a new

meaning by Aminius-Maurice, comte de Saxe, marechal de France,

was one of the most successful generals of the War of Austrian

Succession (1741-1748). Marshal Saxe won his battles using a field army

that fought in a single mass formation. "At best, they were divided

only temporarily into wings or what might be called divisions; but

because these formations had no ongoing identity they could develop

little inner cohesion and only a limited capacity for independent

maneuver." [3] Marshal Saxe recognized this

organizational weakness and offered a solution in a treatise entitled

Mes Reveries published in 1756, six years after his death.

Deploring the historical European practice of recruiting volunteers by

fraud and impressment, he envisioned a system of universal service for

manning French armies. Citizen-soldiers enlisted under Marshal Saxe's

plan would be trained and organized in tactically self-sufficient units

made up of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. Saxe felt that ten of these

legions, totalling 34,000 foot soldiers and 12,000 horse soldiers, would

be suitable for France's military needs. In Mes Reveries he

concluded that "a general of parts and experience, commanding such an

army, will always be able to make head against one of a hundred thousand

for multitudes serve only to perplex and embarrass." [4] While Saxe advocated the creation of divisions within

armies, the implementation of his ideas would became the achievement of

another marechal de France.

During the Seven Years War (1756-1763),

Victor-Francois, duc de Broglie marechal de France produced one

of the few French victories of the conflict against the Prussian army of

Frederick the Great at Bergen in 1759. This victory was possible because

Marshal Broglie had applied Saxe's theory of concentrating divisions.

Unfortunately for Broglie's fortunes, he ran afoul of King Louis XV (and

the King's powerful mistress Madame de Pompadour) and was dismissed from

army command in 1761. Marshal Broglie reversed his fortunes in the late

1760s with the help of Etienne Francois, duc de Choiseul, the French War

Minister, and became the principal supporter of the creation of

divisions in the French Army. Since the creation of divisions can be

viewed as one of the most important innovations in tactics and

organization of combat forces in the Western world, Marshal Broglie

aptly deserves the title of "father of the modern division." [5]

Broglie's concept was to organize divisions as

permanent formations in the French army; however, the tactical

consequences of such an organization were far more complex than the

simple nature of his idea. An army marching in divisional formations

could quickly advance over multiple roads on a very wide front as it

sought contact with the enemy, while at the same time reducing its

logistical problems. Since the division was a "micro" army having

proportionate shares of infantry, artillery, and cavalry, a single

division could, upon first contact with the enemy army, sustain itself

in combat until reinforcing divisions arrived. Single or multiple

divisions might also hold the attention of the enemy in the front while

additional divisions maneuvered around the flanks of the enemy or even

cut the enemy line of communications (i.e., supply line). Division

commanders could operate independently, therefore, simplifying the

command and control problems of the army commander. These were the

theoretical products of Marshal Broglie's simple operational idea. [6]

A young protege of Marshal Broglie, Jacques Antoine

Hippolyte, comte de Guibert, Colonel, would further explore the

potential of a division in combat in his famous Essai general de

tactique published in 1772. Although Guibert's essay does not

advocate the new permanent divisions over the temporary tactical

division formations of the past, he did recognize that the divisional

formations would permit a higher degree of mobility for strategic

maneuver. Guibert also theorized about the formation of a citizen's army

in France. Guibert's citizen's army would harness the energy of the

nation and return the French to the glory it enjoyed before the Seven

Years War. In 1773 he travelled to Prussia and discussed the art of war

with the Prussian King, Frederick the Great.

Thereafter, Guibert developed a keen interest in the

Prussian system of a small, highly trained, professional army. He was

employed by the French Minister of War, Claude Louis, comte de Saint

Germaine, from 1775-1777 in reforming the French Army through the

introduction of Prussian standards of training and discipline.

Interference by King Louis XIV; rumblings of discontent in the Army; and

the resignation of Saint Germaine led to the failure of the reforms.

Guibert, however, was promoted to marechal-de-camp (equivalent of

Major General) and exiled to provincial duty.

Although he recanted his earlier ideas of a citizen's

army in a second work entitled "Defense du systeme de guerre

moderne" written in 1779, his original ideas would inspire

conscription (levee en masse) during the French Revolution. [7] The levee en masse proclaimed on August 23, 1793

provided the manpower for the French Revolutionary Wars and for the

armies which Napoleon Bonaparte used to terrorize Europe from 1797 to

1815.

Formalization of the division concept in the French

Army began just before the outbreak of the French Revolution with the

publication of the ordonnance of March 17, 1788 that specified

that infantry and cavalry brigades be organized in two regiments.

While this feature of the ordonnance was found

unworkable, the Army eventually organized into the twenty-one

administrative divisions authorized by the ordonnance. These

divisions were suitable for meeting French wartime requirements. The

typical French division of 1793 was organized into two brigades

comprised of twelve infantry battalions, two cavalry squadrons, and

twenty-two cannons. A further refinement in 1794 found French divisions

organized into three "demi-brigades." During the Napoleonic period the

French divisional system assumed greater importance. [8]

During the French Revolutionary Wars, flexible French

divisions outmaneuvered their adversaries. However, when acting alone, a

division had a serious limitation. A division lacked the manpower and

combination of arms to continue sustained combat when it met in battle a

significantly larger enemy force. Napoleon recognized this limitation in

1805 and introduced the corps d'armee—the next stage in the

hierarchical organization of the French Army. The corps d'armee

(army corps) was much more than a division could be because it was a

miniature army. Up to this point, the French had combined all the combat

arms (infantry, cavalry, artillery) into the division.

With the formation of the army corps, the French now

discarded the combination of the infantry and cavalry in the division.

Now, the mobile independent cavalry division could exert an impact on

the battlefield that it could not have otherwise. The army corps

generally did not have a fixed organization, but it was always organized

around a number of infantry divisions, a division or brigade of cavalry,

and a battery of twelve-pound guns, controlled by the corps commander,

and supporting logistical services. The infantry division retained its

own artillery. The army corps provided the army commander great

maneuvering flexibility and it had the ability to stand up in a fight

against a force of superior size. More importantly, the army corps

concept fit superbly into Napoleon's favorite form of attack known as

la manoeuvre surles derrieres (cutting off an enemy from his

line-of-communications). [9]

The wartime use of the army corps organization would

not be used in the American Army until the Civil War. However, the use

of divisional organizations can be traced to the American Revolution.

General George Washington organized the thirty-eight regiments of the

Continental Army in 1775 into six brigades (each with generally six

regiments), and then into three divisions (each with two brigades).

However, the divisions and brigades of the Continental Army functioned

only as administrative headquarters. The Continental Army "battalion"

was the basic maneuver unit on the battlefield against the British.

Battalions were comprised of the same men that formed the "regiments"

recruited by the individual colonies. The "regiment" became an

administrative term for men who fought in the tactical "battalion."

Washington molded his tactics on his contemporary understanding of

European warfare. Since the development of the "division" was a

post-French Revolution innovation, Washington's Continental Army did not

fight by divisions and brigades, but rather, as a tactical whole. [10]

In its next encounter with the British during the War

of 1812, the U.S. Army did not adopt the division and army corps

organizations already implemented by the European armies. On June 18,

1812, the day Congress voted for war, the Regular Army consisted of

seventeen infantry regiments, four artillery regiments, and two dragoon

regiments. Later that month, the number of infantry regiments was

increased to twenty-five by standardizing the size of a regiment at ten

companies of ninety privates each. The Army fought the major engagements

of the War of 1812 in much the same tactical manner as the Revolutionary

War without divisions per se. Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown led an American

field army composed of two Regular Army brigades across the Niagara

River in July 1814 and defeated British regulars at the battle of

Chippewa. The War of 1812 ended on favorable terms for the United

States, but it spawned a hundred-year long debate within the nation

concerning the efficacy of a large-standing peacetime regular army

versus the traditional militia-based citizen's army. [11]

American soldiers fighting in the Mexican War from

1846-1848 would be the first American soldiers systematically organized

into combat divisions. These divisions proved to be the type of

self-supporting tactical organizations that the Army needed to fight the

campaigns of the Mexican War which were fought over long distances, in

rugged terrain, and under harsh climatic conditions. Army divisions

proved their worth as units of tactical maneuver. [12]

Although the division proved to be an effective

tactical innovation during the Mexican War, the Army found that it was

difficult to identify officers who were capable of leading a

sophisticated combat formation as large as a division. Most division

commanders were appointed because of Regular Army seniority or political

connections. The strength of the American Army in Mexico centered around

its young officers, especially graduates of West Point, and its enlisted

soldiers. The army proved that small cadres of officers and

non-commissioned officers who knew how to soldier could make efficient

soldiers out of volunteers in short order. [13]

Regimental and divisional staff duty in Mexico prepared Lee, McClellan,

Grant, Meade, and many others for brigade, division, corps, and army

command thirteen years later.

At the close of the Mexican War, brigades and

divisions were quickly disbanded because they were viewed by the War

Department as temporary wartime tactical organizations that the

government could ill afford in peacetime. The small Regular Army

returned to regimental garrison duty at camps and forts around the

United States and along the frontier. For administrative purposes, the

War Department divided the country into large territorial departments to

which the regiments would be assigned. These military departments

persisted throughout the Civil War and existed simultaneously with the

tactical armies, corps, and divisions that operated within their

borders. This perplexing system created an unwanted administrative

burden to tactical field commanders who were also appointed commanders

of the military departments. [14]

The organization and administrative operation of the

U.S. Army from 1821 to 1881 was based on a one-volume set of

periodically revised 'General Regulations' issued by the War Department.

Rapid expansion of the Army for the Civil War forced the War Department

to update the 1857 version of the "General Regulations" and issue the

Revised Regulations for the Army of the United States, 1861 on

August 10, 1861. While the majority of the 559 pages of this document

are consumed with the vast administrative details of running an army,

Article XXXVI, entitled Troops in Campaign specifies that "the

formation by divisions is the basis of the organization and

administration of armies in the field." Furthermore, Article XXXVI

states that "a division consists usually of two or three brigades,

either of infantry or cavalry, and troops of other corps in the

necessary proportion" and that "a brigade is formed of two or

more regiments." [15] These doctrinal definitions

provided the Union Army a framework for mobilization as it organized

brigades and divisions to provide tactical control to the multitude of

state-raised regiments of volunteer soldiers. During the course of the

war, brigades usually consisted of from two to six regiments and

divisions were formed with two or more brigades. The most common

alignment during the war was five regiments to a brigade and three

brigades to a division. [16]

While the division would remain an important tactical

organization throughout the war, by 1862 it would be eclipsed as the

basic larger unit formation of the army by the army corps made up of two

or more divisions. As early as July 19, 1861 a War Department order

contained language about the formation of "Corps d'Armee" on the

French model. Late in 1861, President Lincoln recommended to General

McClellan that the fifteen divisions of the ponderous Army of the

Potomac would operate better if organized into army corps. While Lincoln

ordered McClellan to organize army corps in March 1862, Congress did not

authorize the President to form army corps at his discretion until July

17, 1862. McClellan demurred over the formation of army corps because he

felt that there were no officers who had proven themselves as corps

commander material. It would also prove difficult to find officers who

could handle both the administrative and combat duties associated with a

large division. [17]

The U.S. Army combat division of today has much in

common with the Civil War division of 1863. The modern division

"consists of a relatively fixed command, staff combat support, and

combat service support structure to which maneuver battalions are

assigned." [18] The Civil War division had a

similar structure which consisted of a command group, a general staff,

logistical support organizations, and two to five maneuver infantry

brigades. Artillery support for infantry divisions varied between the

Union and Confederate armies. At Gettysburg each Confederate division

had an organic artillery battalion, while Union divisions were allocated

artillery support as needed from their corps artillery brigades or the

army artillery reserve.

The command group of the Civil War division consisted

of the division commander and his personal staff, normally a variable

number of commissioned officer Aides-de-camp (ADCs). The division

commander was assigned to his duties by the general commanding-in-chief

of the army or directly by the War Department. [19] He

discharged his command responsibilities through an established

organization of command delegations called a chain-of-command.

Army Regulations granted General Officers the authority to appoint their

own ADCs. [20] It was common practice for Civil War

generals to appoint friends or family members as ADCs. In a time when

the speed of communications on the battlefield was only as fast as a

horse, the ADCs performed the critical function of receiving and

distributing the commanding general's orders to the brigade commanders

or delivering messages to adjacent or higher headquarters.

The General staff of the division existed for one

purpose—to assist the division commander in accomplishing whatever

mission he was given to accomplish. The evolution of the Civil War

division staff began during the American Revolution when Washington

organized administrative and logistical staffs for the Continental Army

based on British precedents. [21] While the Army had

developed some rudimentary principles concerning the organization and

functions of a division staff as a result of the Mexican War experience,

this experience had not been documented in any sort of War Department

manual or regulation by the start of the Civil War.

In 1855 the War Department sent a Commission of

officers to observe the European armies, then engaged in fighting the

Crimean War. The Commission produced voluminous reports on their

observations of the organization and war fighting techniques of the

British, French, and Russian armies. The individual reports of Maj.

Alfred Mordecai, Ordnance Corps, and Capt. George B. McClellan, Corps of

Engineers, contained detailed descriptions of the type of military

staffs used by these armies. Subsequent development of military staffs

in Civil War field armies can be linked to the observations of the

European Commission. [22]

During the Civil War, the maintenance and business

management of the U.S. Army came from the various bureaus of the War

Department. These bureaus included the Adjutant General, the

Quartermaster General, the Surgeon General, the Judge Advocate General,

the Chief of Ordinance, the Commissary General, the Paymaster General,

the Chief of Engineers (the Corps of Engineers was consolidated with the

Corps of Topographical Engineers on March 3, 1863), the Chief Signal

Officer, and the Provost Marshal General. [23] Staff

officers in the field armies were the representatives of the various

military bureaus of the War Department. Since there could be only one

chief of a bureau for the entire War Department, all officers serving

similar functions on the military staffs of the field armies, corps,

divisions, and brigades throughout the Army used the title "Assistant"

in front of their job title. This technical channel of staff hierarchy

gave the field staff officer a link with his bureau in the War

Department.

The Army was a bureaucracy that required tons of

paper reports to make it function. Feeding this paper mill were the

field staff officers who were required by the General Regulations of

1861 to submit countless forms, returns, reports and requisitions to

administer and maintain their units. For instance, a brigade assistant

adjutant general (AAG) would submit monthly strength returns (reports)

through the division and corps AAG where they were consolidated by the

army AAG for submission to the War Department. [24]

Divisional staff officers like the Assistant Quartermaster, the

Assistant Commissary officer, the Assistant Ordnance officer, and the

Medical Director submitted similar reports in order to provide

logistical support to the maneuver brigades of the division. The combat

efficiency of the division could be measured by the quality of the

division staff. Perhaps the greatest challenge to a Civil War division

commander was to train and nurture his staff so that it could perform

well during combat conditions.

By virtue of the solid combat performance of the

Second Division, Third Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac at

Gettysburg, it is apparent that Brigadier General (BG) Andrew Atkinson

Humphreys, the division commander, understood the importance of a

well-trained and motivated battle staff. At Gettysburg his staff would

serve him well during some of the most ferocious fighting encountered by

an infantry division during the course of the war. Finding officers

capable of training battle staffs and maneuvering infantry divisions on

the battlefield proved difficult for Civil War armies simply because no

pool of large unit leaders existed at the outset of hostilities.

Humphreys' rise to divisional command was typical of many Regular and

Volunteer officers swept up in the rapid expansion of the Army. A

Captain in the pre-war Regular Army, Humphreys ascended to command of an

infantry division without the benefit of even regimental command

experience and without Mexican War combat experience. In spite of rapid

wartime promotions, however, the road to divisional command for many

Regular officers was very long. Humphreys commanded his first division

in combat after twenty-nine years service in the Regular Army.

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on November 2,

1810, Humphreys was fifty-two years old at the time of the Gettysburg

Campaign. His father, Samuel, and grandfather, Joshua, were both naval

architects and ship builders. His grandfather drew the plans for the

frigate Constitution, better known as Old Ironsides. [25] A full summary of Humphreys service record is shown

in Figure 1. He graduated from the United States Military Academy at

West Point on July 1, 1831, finishing thirteen in a class of

thirty-three. The same day he was appointed a brevet Second Lieutenant

of Artillery and, subsequently, assigned for duty with the Second

Artillery Regiment at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina.

| Dates | Position/Organization/Location |

| 1827-1831 |

Cadet. USMA, West Point, NY - Graduated Class of '31 [13/31] |

| 1831 | (July 1) |

Appointed Brevet 2nd Lt., Artillery, 2nd Arty Regt., Ft. Moultrie, SC |

| 1832 | (Jan 6-Apr 18) |

Detailed to duty at USMA (Dept. of Engineering), West Point, NY |

| 1832 |

Brevet 2nd Lt., Battery B, 2nd Arty Regt., Cherokee Nation, SC |

| 1833 |

Acting Assistant Quartermaster, Augusta Arsenal, GA & Ft. Marion, FL |

| 1834-35 |

Duty with Corps of Topographical Engineers surveying roads in FL |

| 1836 | (Apr-Sep) |

Seminole Indian War service |

| (Aug 16) |

Promoted to 1st Lt., Artillery |

| (Sep 30) |

Resigns Commission |

| 1837-38 |

Break in active service - Civil Engineer, Chicago, IL |

| 1839 | (Jul 7) |

Commissioned 1st Lt., Corps of Topographical Engineers, Washington, DC |

| 1840 |

Assistant at Topographical Bureau, Washington, DC |

| 1841-42 |

Map Survey in Florida |

| 1842-44 |

Assistant at Topographical Bureau, Washington, DC |

| 1844-48 |

Assistant-in-charge, Coast Survey Office, Washington, DC |

| 1848 | (May 31) |

Promoted to Capt., Corps of Topographical Engineers |

| 1849-61 |

Detailed to Mississippi River Delta topographic/hydrographic survey |

| 1853-54 |

Visits Europe to study means to protect river deltas from inundation |

| 1854-61 |

Assigned to War Department in charge of exploration from the Mississippi

River to the Pacific Ocean |

| 1856-62 |

Member of the Lighthouse Board |

| 1861 | (Aug 6) |

Promoted to Maj., Corps of Topographical Engineers |

| 1861 | (Dec 1) |

Engineer Staff Officer to Army General-in-Chief, Washington, DC |

| 1862 | (Mar 5) |

Appointed as Col., U.S. Volunteers and additional Aide-de-camp |

| (Mar 5-May 4) |

Chief Topographical Engineers, Army of the Potomac |

| 1862 | (Apr 28) |

Promoted to Brig. Gen., U.S. Volunteers |

| (Sep 12) |

Commanding General, 3rd Div., Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac |

| (Dec 13) |

Brevetted to Col., U.S. Army for bravery at Fredericksburg |

| 1863 | (Mar 3) |

Promoted to Lt. Col., Regular Army, Corps of Engineers |

| (May 23) |

Commanding General, 2nd Div., Third Corps, Army of the Potomac |

| (July 8) |

Promoted to Maj. Gen., U.S. Volunteers |

| (July 9) |

Chief of Staff, Army of the Potomac |

| 1864 | (Nov 25) |

Commanding General, Second Corps, Army of the Potomac |

| 1865 | (Mar 15) |

Brevetted to Brig. Gen., U.S. Army for bravery at Gettysburg |

|

|

Brevetted to Maj. Gen., U.S. Army for bravery at Sailor's Creek |

| (May 23) |

Grand Review of the Army of the Potomac, Washington, DC |

| (Jun 27) |

Demobilization of the Army of the Potomac |

| (Jun 28-Dec 9) |

Commander, District of PA, Middle Department |

| 1866 |

Placed in charge of the Mississippi Levees |

| (May 31) |

Mustered out of volunteer service |

| (Aug 6) |

Appointed to command of the Corps of Engineers with rank of Brig. Gen.

& Chief of Engineers |

| 1879 | (Jun 3) |

Retired from active service in the U.S. Army |

| 1883 | (Dec 27) |

Dies of stroke at age 73 and buried in Congressional Cemetery, Wash, DC |

BATTLE CAMPAIGNS:

| Indian Wars: |

Seminole War (Dec 28, 1835 - Aug 14, 1842) |

| Civil War: |

Peninsula (Mar 17 - Aug 3, 1862), Antietam (Sep 3-17, 1862),

Fredericksburg (Nov 9 - Dec 15, 1862), Chancellorsville (Apr 27 - May 6,

1863), Gettysburg (Jun 3 - Aug 1, 1863), Bristoe (Sep 14 - Oct 14,

1863), Mine Run (Oct 15 - Dec 2, 1863), Wilderness (May 4-7, 1864),

Spotsylvania (May 8-21, 1864), Cold Harbor (May 22 - Jun 3, 1864),

Petersburg (Jun 4, 1864 - Apr 9, 1865); Appomattox (Apr 3-9,

1865) |

ORGANIZATIONS & SOCIETIES:

Honorary Doctor of Laws, Harvard College, 1868

Member, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA

Member, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Boston, MA

Corporator, National Academy of Sciences

Honorary Member, The Imperial Royal Geological Institute of Vienna

Honorary Member, The Royal Institute of Science and Art of Lombardy, Italy

Corresponding Member, The Geographical Society of Paris

Corresponding Member, The Austrian Society of Engineer Architects

PUBLICATIONS:

Report upon the Physics and Hydraulics of the

Mississippi. Co-authored with Henry L. Abbot. War Department, Corps

of Topographical Engineers, 1861.

The Pennsylvania Campaign of 1863. The

Historical Magazine, Volume VI, Second Series, Morrisania, New York,

1869.

From Gettysburg to the Rapidan, The Army of the

Potomac - July 1863 to April, 1864. Charles Scribner's Sons, New

York, 1883.

The Virginia Campaign of '64 and '65, The Army of

the Potomac and The Army of the James. Charles Scribner's Sons, New

York, 1883.

In 1836, following limited service in the Seminole

Indian War, he resigned his commission in the Regular Army and became a

Civil Engineer in Chicago, Illinois. Humphreys reentered the Army two

years later in 1838 and was commissioned as a First Lieutenant in the

Corps of Topographical Engineers. [27] In 1838 the

Corps of Topographical Engineers, informally known as "topogs", was

established as a separate corps when thirty-six authorized officers were

placed on the same footing with the more numerous Corps of Engineers.

"Topogs" were responsible for the topography, mapping, and civil

engineering works authorized by Congress. After this realignment, the

larger Corps of Engineers would concentrate on providing combat support

to the field armies and in building coastal fortifications. [28]

Andrew Humphreys' duties as a "topog" at the War

Department kept him out of the Mexican War and denied him important

combat experience. Between 1849 and 1861 he attained prominence as a

Civil Engineer when he was placed in charge of the topographic and

hydrographic survey of the delta of the Mississippi. The publication of

Humphreys' Report Upon the Physics and Hydraulics of the

Mississippi (which he wrote with 1st Lt. Henry L. Abbot) in 1861 by

the War Department resulted in world-wide acclaim for his Civil

Engineering accomplishments. [29] Promoted to Major of

Topographical Engineers on August 6, 1861, Humphreys began his war

service in Washington as the Engineer Staff Officer to the Army

General-in-Chief McClellan. Promoted to temporary Colonel on March 5,

1862, he served as Chief Topographical Engineer of the Army of the

Potomac during the Peninsular Campaign.

Humphreys combat performance as the Chief

Topographical Engineer of the Army of the Potomac greatly impressed

General McClellan. Observing that Humphreys had the technical expertise

and leadership potential to command a large combat unit, McClellan

supported Humphreys' promotion to Brigadier General of U.S. Volunteers

dating from April 28, 1862. Three months later Humphreys was selected to

command the Third Division, Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac at the

outset of the Antietam Campaign. [30]

Humphreys first experience as a division commander

would be frustrating. With the battle of Antietam imminent he assumed

command of his division on September 12, 1862, at Alexandria, Virginia.

The two infantry brigades constituting his division were made up of

untrained rookie soldiers from Pennsylvania. Seven of the eight infantry

regiments in the division had entered Federal service during the first

week of August and half of them were equipped with Austrian rifles that

were inoperative. Humphreys drove these troops on a long and rugged road

march to join the Army of the Potomac arriving at Frederick, Maryland,

September 16. On September 17, Humphreys received orders to join the

Army by 2:00 P.M. the next day as the battle raged at Antietam.

Notifying General McClellan that his division would march all night, but

would arrive fit for combat, Humphreys lived up to his promise. After a

difficult all night twenty-three mile march, his division, missing only

600 of 6,600 soldiers to straggling, was ready for combat as part of the

Army's reserve by 10:00 A.M. on September 18.

Humphreys was outraged by McClellan's initial battle

report because the report stated that Humphreys Division of rookie

soldiers arrived unfit for combat. Humphreys request for a War

Department court of inquiry to clear his reputation forced McClellan to

amend his first report accordingly. [31]

Humphreys received a bloody baptism of fire on

December 13, 1862, at the battle of Fredericksburg for at 5:00 P.M. his

division was used as the fifth, and final, attacking column in the

ill-fated attempt of the Union Army to storm Confederate positions along

the stone wall at the base of Marye's Heights. Capt. Carswell McClellan,

one of Humphreys' ADCs, described his division commander in the assault

as follows

Colonel Allabach having been directed to form his

brigade in two lines, General Humphreys rode out into the field to

observe the ground more closely. As he did so, Colonel Barnes,

commanding the First Brigade of General Griffin's division, walked over

from beyond the left of our line and met him. After exchanging a few

words with Colonel Barnes, and after again glancing over the, General

Humphreys, while riding back toward his troops, said to his adjutant

general; 'M—, the bayonet is the only thing that will do any good

here,—tell Colonel Allabach so, and direct him to see that all

muskets are unloaded.' Colonel Allabach, a sturdy graduate from the

'Bloody Third' U.S. Infantry of the Mexican war, rode through his

command with his staff as the formation was being completed, and had the

muskets 'rung' to prove them all unloaded, then, with the brigade

formed, the front line at 'charge bayonets' and the second line at

'right shoulder arms,' he reported his command ready to move forward. As

the bugle sounded the charge, General Humphreys turned to his staff and

bowing with uncovered head, remarked as quietly and pleasantly as it

inviting them to be seated around his table; 'Gentlemen, I shall lead

this charge; I presume of course, you will wish to ride with me.'

[32]

Despite his personal bravery, both of Humphreys'

brigades quickly gave way when exposed to the full force of the

Confederate fire and sustained losses that included 1,760 killed,

wounded, and captured soldiers, slightly less than fifty percent of the

division. [33]

At the battle of Chancellorsville in early May 1863,

Meade's Fifth Corps, to which Humphreys Division was assigned, was used

sparingly. Humphreys main action came at the end of the battle as the

Fifth Corps was ordered to cover the withdrawal of Hooker's defeated

army back across the Rappahannock River. Fortune smiled on Humphreys

Division at Chancellorsville, however, because it sustained only 277

casualties (22 killed, 197 wounded, and 55 missing). [34] This was welcome news to the men of Humphreys

Pennsylvania regiments because their terms of service expired at the end

of May.

Humphreys Third Division was dissolved on May 23,

1863 (a month later the Pennsylvania Reserve Division from the XXII

Corps would reconstitute this division in the Fifth Army Corps). [35] Humphreys, now with nearly nine months of command

experience, would not remain idle On May 23, 1863 he assumed command of

the Second Division, Third Army Corps, replacing Brig Gen Hiram G. Berry

who had been killed-in-action at Chancellorsville. He entered the

Gettysburg Campaign commanding his second division of the war. [36]

What sort of man was Andrew A. Humphreys at the onset

of the Gettysburg Campaign? Physically he closely resembled his

grandfather, Joshua Humphreys, who was described as being

of short stature, about five feet eight inches in

height, large chest, long body and arms, with short legs. His bones were

those of a man of six feet. His head was large, beautifully shaped,

surmounted in his old age by a thick mane of curling gray hair. His eyes

were steel gray in color, large and open, and exceedingly piercing; his

mouth large, well-shaped and firm; nose, large and of Grecian

form... [37]

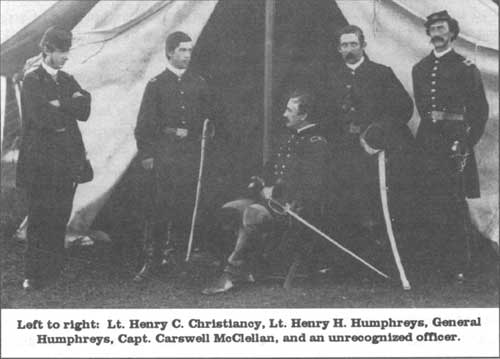

All these features are clearly visible in the June

1862 photograph of a newly-minted General Humphreys shown in

Figure 2. Unlike the formal studio portraits of the era, this photograph

shows a grizzled Humphreys wearing an non-regulation campaign

uniform—a private's sack coat with general epaulets sewn on the

shoulders. [38] It is very likely that this photograph

approximates Humphreys' actual field appearance at Gettysburg.

Positive and negative insights into Humphreys

personality were recorded by a number of observers. 1st Lt. Henry L.

Abbot, Humphreys' pre-war Civil Engineering colleague, wrote that

"General Humphreys exerted a personal magnetism which can hardly be

expressed in words. His manners were marked by all the graceful courtesy

of the old school, while the unaffected simplicity and modesty of his

character, and the force and vigor of his ideas, left an impression not

easily effaced." [39]

Col. Theodore Lyman, a Volunteer ADC for Meade,

observed that "he [Humphreys] is a an extremely neat man, and is

continually washing himself and putting on paper dickeys. He has a great

deal of knowledge, beyond his profession, and is an extremely

gentlemanly man." [40] Lyman also commented that

"he is most easy to get on with, for everybody; but, practically, he

is just as hard as the Commander [Meade], for he has a tremendous

temper, a great idea of military duty, and is very particular. When he

does get wrathy, he sets his teeth and lets go a torrent of adjectives

that must rather astonish those not used to little outbursts." [41]

Another observer, Charles Dana, was more succinct

about Humphreys' outbursts by stating that "he was one of the loudest

swearers I ever knew." [42] A less admiring

portrait was provided by Maj. Gen David Bell Birney who secretly

confided to a friend that "Humphreys...is what we call an old granny,

a charming gentlemen, fussy and numbed to troops. [43]

Humphreys possessed a keen intellect and

extraordinary soldiering skills. Dana found Humphreys to be a formidable

general and considered him a complete package—a strategist,

tactician, and an engineer. More importantly, Humphreys was a "fighter,"

a trait which Dana found rather exceptional for an engineer. [44] Lyman reported that Humphreys considered professional

soldiering as a "godlike occupation" and that "war is very bad

in sequel, but before and during a battle it is a fine thing!" [45] However, Humphreys pre-war experience in the

Topological Engineers did little to prepare him for leading a large

division. He, like thousands of Volunteer officers, probably learned the

mechanics of maneuvering troops in battle by judiciously studying the

popular tactical handbooks of the day (such as Hardee's Rifle and

Light Infantry Tactics or Brig. Gen Silas Casey's Infantry

Tactics); by subjecting his division to monotonous battle drills;

and, most importantly, by experiencing the crucible of combat.

There are differing views of Humphreys as a military

leader. Henry Abbot provides the following insights into Humphreys

military leadership style

In official relations General Humphreys was

dignified, self-possessed and courteous. His decisions were based on

full consideration of the subject and, once rendered, were final. He had

a profound contempt for every thing which resembled double-dealing or

cowardice. He scorned the arts of time servers and demagogues; and when

confronted with meanness, took no pains to conceal his indignation no

matter what might be the rank or position of the offender. He felt the

warmest personal interest in the success of his young associates, and

often did acts of kindness of which they learned the results but not the

source. [46]

Conversely, Harry Pfanz, noted Civil War historian,

concluded that Humphreys "had little charisma and was not a popular

commander" and that he earned the sobriquet of "Old Goggle

Eyes" because he wore spectacles and was a strict disciplinarian.

[47] How volunteer soldiers and young staff officers

of Humphreys division reacted to Humphreys brand of leadership would be

shown on the fields of Gettysburg.

Humphreys left a splendid official report describing

his actions during the battle. Of all the battle reports written during

the war, Humphreys Gettysburg report is a model of clarity and

completeness. In the report Humphreys made a great effort to officially

recognize the key combat leaders of the division and all of his

divisional staff officers. Recognizing the unique quality of the report,

the editor of The Historical Magazine first published it in 1869.

Humphreys was nonplussed about the notoriety of the report because in a

letter which accompanied the article he stated

my official Report is, of course, a lifeless

affair, an exact statement of facts which have a certain value, but that

which makes the thrilling interest of a battle is the personal incident;

and of that I could, if I had some leisure, tell a good deal, but I feel

fatigued, and unwell, and quite unable to attempt a description of what

took place at Gettysburg, under my own eye. A battle so lifts a man out

of himself that he scarcely recognizes his identity when peace returns,

and with it quiet occupation. [48]

Despite Humphreys later reservations, his Gettysburg

report with its first-hand impressions of the battle provides a clear

picture of a Civil War division in action. Twenty years later, in 1889,

Humphreys' report was again published as part of the War Department's

official compilation of Civil War records. [49]

Humphreys Division entered the campaign as the second

of two divisions that constituted the Third Army Corps commanded by Maj.

Gen. Daniel Sickles. Humphreys had little direct contact with his new

corps commander during the early stages of the campaign because Sickles

was on leave in New York City recovering from the effects of a minor

wound from Chancellorsville, [50] By virtue of

seniority General Birney, the First Division Commander, was "acting"

corps commander during much of the approach march. General Sickles

resumed command of the Third Corps at Frederick, Maryland on June 28,

1863. The absence of the corps commander and the rapid movement of the

Army of the Potomac into Pennsylvania provided Humphreys little

opportunity to observe the charismatic Dan Sickles in command. Humphreys

was an outsider in the Third Corps simply because he was a career

officer. Volunteer officers like Sickles and Birney were known to have

ridiculed the fighting abilities of West Point trained regulars like

Humphreys. Conceivably, Sickles and Birney were even intimidated by

Humphreys intellectual skills and his reputation as a

disciplinarian.

When Humphreys' Division left its camp at Falmouth,

Virginia, on June 11, 1863, it was organized into three maneuver

brigades. The First Brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Carr,

made up of seven regiments (a total of seventy companies), had a

reported field strength on June 30, 1863 of 2,241 soldiers (164 officers

& 2,077 enlisted men), but engaged only 1,718 soldiers in the

battle. Col. William R. Brewster's "Excelsior Brigade" (the Second

Brigade) consisted of six New York regiments (sixty companies) and

engaged 1,837 soldiers in the battle from a reported June 30 strength of

2,269 (140 officers & 2,129 enlisted men). The Third Brigade,

commanded by Col. George C. Burling, made up of six regiments

(fifty-nine companies), had a reported field strength on June 30 of

1,606 soldiers (105 officers & 1,501 enlisted men), but engaged only

1,365 soldiers in the battle.

Humphreys total divisional strength, as reported by

pay day muster on June 30, was 6,120 soldiers (413 officers & 5,707

enlisted men), but only 4,924 soldiers would actually fight at

Gettysburg. [51] The disparity in numbers between men

assigned on June 30 and those who actually fought two days later is a

reflection of the severity of the division's exhaustive road march into

the battle area. Even Humphreys, the strict disciplinarian, found it

difficult to keep his division intact on the approach march.

(click on image for a PDF version)

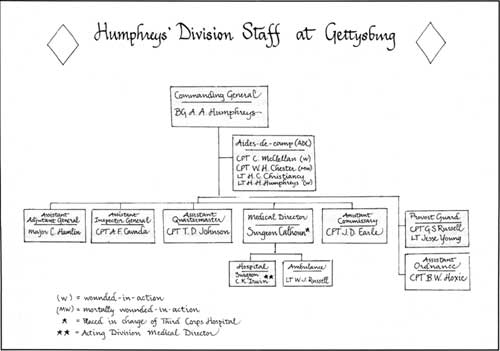

Assisting Humphreys in managing the division and

controlling it in combat was his general staff. The division staff also

performed critical logistical functions. An organizational chart of

Humphreys' staff during the Gettysburg Campaign is shown on page 149. In

battle the division commander relied heavily on his ADCs to transmit and

deliver orders to subordinate commanders and to perform tactical trouble

shooting as required. ADC duty was especially hazardous as mounted

officers made lucrative targets for enemy marksmen. While the ADC had no

command authority, he was the personal representative of the division

commander. Orders given through an ADC had to be followed as if the order

was given by the division commander himself. The photograph shown on

page 154 was taken in September 1863 and shows General Humphreys posing

with three of the four young ADCs who served him at Gettysburg. [52] Humphreys' Assistant Inspector General (AIG), Capt.

Adolfo Cavada, also performed duties similar to an ADC at

Gettysburg.

At Falmouth, Virginia, on June 11, 1863, Humphreys'

Division began a series of long, hot forced marches as the Army of the

Potomac raced for a showdown with Lee's army. As his division passed

through Frederick, Maryland, on June 28, Humphreys was summoned to army

headquarters for an interview with the new army commander, General

Meade. Meade, who had relieved Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker of command of the

army that very same day, wanted Humphreys to be his Chief-of-Staff.

Humphreys declined the post and told Meade he could be of greater

service in command of his division during the impending battle. [53] Two more days of road marches brought Humphreys'

Division to Emmitsburg, Maryland, on the morning of July 1 in the van of

the Third Army Corps.

Leading elements of Meade's Army of the Potomac and

Lee's Army of Northern Virginia collided earlier that morning a few

miles north of the Pennsylvania border at Gettysburg and by late

afternoon a full-blown battle was raging. Humphreys halted the division

one mile north of Emmitsburg at about 11:00 A.M. and awaited further

orders from Third Corps. [54]

Shortly thereafter, Humphreys received orders through

Third Corps directly from General Meade to perform a reconnaissance of

the ground north of Emmitsburg. Meade was using Humphreys' topographical

engineering experience to explore optional battle lines for the army

because he had not yet decided to fully concentrate the army at

Gettysburg. Humphreys left the division under the temporary command of

General Carr, First Brigade, and accompanied by his Capt. Cavada,

proceeded to examine the ground north of Emmitsburg. At about 3:00 P.M.,

General Carr received orders from Third Corps Headquarters to "move

with the utmost dispatch" to Gettysburg and to report to General

Howard "who was engaged with the enemy there." [55] This order also directed the Second Division to leave

a brigade and an artillery battery at Emmitsburg to guard a possible

enemy advance from the west along the Waynesborough Road. Accordingly,

Colonel Brewster's Third Brigade and Smith's Battery stayed behind at

Emmitsburg as the First and Second Brigades started the twelve-mile road

march to Gettysburg. [56]

To expedite rapid movement of the Third Corps,

Birney's Division marched north on the main road from Emmitsburg while

Humphreys' Division was directed to a country wagon road angling off to

the northwest of the Emmitsburg Road. Humphreys finished his

reconnaissance mission and, according to Cavada, "with some

difficulty the Genl. & staff made their way through the mass of men

struggling forward" to overtake the First Brigade a mile north of

Emmitsburg and resume command of the division. [57]

Along the way, Humphreys received some combat

intelligence and more orders from the Third Corps. He saw a copy of a

dispatch from General Howard that warned Sickles to guard his left from

the enemy as he approached Gettysburg. He was also told by a local

citizen that there were no Union troops west of the Emmitsburg Road

(only partially true considering the location of Buford's Cavalry

Division). Finally, a Third Corps staff officer arrived with orders

directing Humphreys to "take position on the left of Gettysburg as he

came up." Thus far, the column had been guided by Dr. Anan, a

civilian doctor, but as the division approached Marsh Creek, it was met

by an additional guide, Lieutenant Colonel Hayden, Third Corps AIG. At a

fork in the road short of Marsh Creek, Hayden insisted the division take

the left fork. Hayden claimed that General Sickles had directed him to

lead Humphreys Division into Gettysburg along the Fairfield Road past

the Black Horse Tavern. [58] Based on previous

instructions and a keen sense of terrain, Humphreys objected to this

move, but finally deferred to the judgment of the corps staff officer

who was supposed to know where he was going. Reluctantly, Humphreys

ordered the brigade's columns to close up but to move on quietly in the

darkness of the evening. [59]

After crossing and recrossing Marsh Creek a number of

times, the column turned onto the Fairfield Road about three miles west

of Gettysburg. After proceeding about a mile, Hayden who was 200 yards

in advance of the column with the guides, rode back to Humphreys and

informed him that there were enemy pickets directly ahead on the

Fairfield Road. Given Humphreys' penchant for use of invective language,

it is interesting to ponder his first words to Hayden in response to

this startling news. Alas, the historical record provides no clue.

Humphreys halted the division column and rode forward to the Black Horse

Tavern with Hayden, Dr. Anan, and ADCs McClellan and Humphreys to sort

things out.

Humphreys later recorded that "before reaching the

Tavern that night, I enquired as to the character of the keeper, and

learned that his sympathies were not with us, or not very strongly, at

least; and I therefore relied on what a young man, by the name of

Boling, (a wounded Union soldier, home on leave,) who was there, told me

of the enemy." [60] Confirming the presence of

enemy troops ahead from a captured Confederate artilleryman, Humphreys

quickly realized his division was in the wrong place, so he returned to

the head of the column and ordered the division to face about quietly

and retrace its steps. In 1869, Humphreys visited Mr. Bream, the tavern

owner, and later wrote that

Bream says my troops made a great noise coming up,

talking, etc., but went away so quietly he did not hear them. Now this

is not true; and I told him so. I knew I was coming upon the enemy, and

gave the caution to be quiet. What he heard was the noise of horses, and

artillery, and ambulances, crossing and wading up Marsh run (or Creek)

which has a rocky bottom, and that unavoidable noise that troops make in

crossing a deep wading-stream of irregular depth. Now the ambulances and

artillery did the same thing in returning, and so did some of the

Infantry; the other and greater part of the Infantry did not recross but

kept along the bank. [61]

Humphreys pondered his good fortune to have survived

this incident because he also recorded that

the more intelligent of the two [Bream] sons

mentioned to me, that the enemy's picket line was about two hundred feet

from us, and would have given the alarm in ample time to the main body,

had I attempted to surprise. I was right in not attempting it. The sons

(indeed Bream himself) mentioned that I had not been gone ten minutes

when a party of twenty or thirty of the enemy came up to the tavern and

passed the night there. The chance of war; the day had been rainy and

sultry, and the men longed for a few minutes more at each halt. Had I

rode up to the Black Horse tavern fifteen minutes later, with my party

of five or six, virtually unarmed, what might not have been the result

of a deliberate volley from twenty or thirty muskets or rifles at a

distance of twenty feet?" [62]

The division countermarched by recrossing Marsh Creek

and marching along the road on the west bank of the creek. In moonlight

Humphreys' brigades crossed to the east side of Marsh Creek at the Sachs

covered bridge, forded Willoughby Run, passed Pitzer's Schoolhouse and

proceeded up the gentle western slope of Seminary Ridge. [63] Stopping at a farmhouse (possibly the James Flaharty

property) a mile beyond the schoolhouse Humphreys learned from the

occupants that enemy troops occupied Pitzer's Woods a third of a mile

beyond the house. As a precaution an infantry company was thrown out 200

yards in advance of the division and the march proceeded along the

Millerstown Road (in his report Humphreys called this the Marsh Creek

Road). The way was clear and at the intersection of the Emmitsburg Road

at the Peach Orchard Union cavalry videttes were contacted. [64] The division turned north on the Emmitsburg Road and

were guided into their place in the Third Corps sector along Cemetery

Ridge by Lieutenant Colonel Hart, the Third Corps AAG.

Humphreys' fatigued division ended its very eventful

approach march to Gettysburg and quickly went into bivouac at 1:30 A.M.,

July 2. [65] Most of Humphreys' soldiers probably felt

like Capt. Cavada who recorded that "overcome with fatigue &

sleepiness I threw myself under the nearest tree amid the wet grass, and

in spite of rain & mud was soon lost to everything around me."

[66] After the travails of the days march, Humphreys

had good reason to question the judgement of Third Corps staff officers,

like Lieutenant Colonel Hayden, who had almost led his division to

disaster along the Fairfield Road.

The Second Division commander and his staff were up

and working at dawn on July 2. In his official report Humphreys stated

that his "division was massed in the vicinity of its bivouac, facing

the Emmitsburg road, near the crest of the ridge running from the

Cemetery of Gettysburg, in a southerly direction, to a rugged,

conical-shaped hill, which I find goes by the name of Round top, about 2

miles from Gettysburg." [67] Early morning orders

from Third Corps required Humphreys' Division to relieve the corps

picket line. Capt. Cavada led the relief regiment forward and recorded

that "our picket line at that hour of the day was placed about one

hundred yards beyond the Gettysburg and Emmetsburg road and following

its course for about a mile southward." [68]

Burling's Third Brigade was ordered to rejoin

Humphreys' Division directly by General Meade's headquarters at 1:30

A.M. on July 2. Due to darkness, however, Burling did not begin his

march to Gettysburg until 4:00 A.M. Burling's route of march was

straight up the Emmitsburg Road, but it took him five hours to cover the

twelve miles. He arrived into Humphreys' bivouac position at 9:00 A.M.

and was massed in column of regiments behind the First and Second

brigades. [69] Humphreys' now intact division remained

in this bivouac position until shortly after midday.

During the morning of July 2, events unfolded south

and west of the Emmitsburg road that would cause General Sickles to

embark on a maneuver that stands today as the most controversial

movement of the battle—the occupation of the Peach Orchard line.

[70] With the departure of Buford's cavalry screen at

11:30 A.M. on the left of the Third Corps line and with enemy reported

moving at 12:00 P.M. in the vicinity of Pitzer's Woods by Col. Berdan's

reconnaissance-in-force, Sickles became uncomfortable with the placement

of his corps along Cemetery Ridge. In Sickles judgment, the high ground

along the Emmitsburg Road was a better place to deploy his corps. He had

learned a painful lesson two months earlier at Chancellorsville when his

corps was ordered to abandon the high ground of Hazel Grove, the loss of

which spelled doom for the Army of Potomac that day.

Accordingly, without obtaining the implicit

permission of the army commander, Sickles began moving Birney's division

to the left and forward to the Emmitsburg Road shortly after 12:00 P.M.

By 1:00 P.M. Birney had advanced Ward's Brigade to the vicinity of

Houcks' Ridge, de Trobriand's Brigade to the stony hill above Rose's

wheatfield, and Graham's Brigade to the Peach Orchard. Never during his

decision process for this movement did Sickles seek the technical advice

of Humphreys, a premier topographical engineer. Perhaps Sickles isolated

Humphreys from the decision process because he felt that Humphreys would

have argued against creating a salient at the Peach Orchard and

isolating the Third Corps from the rest of the army. Perhaps Sickles was

simply guilty of the old army adage—"if you don't want the

answer, don't ask the question!..."

At 11:00 A.M. Sickles ordered Humphreys to send a

regiment to the skirmish line along the Emmitsburg Road and Humphreys

complied by sending the First Massachusetts of Carr's brigade to relieve

the Fourth Maine of Ward's Brigade which immediately returned to its

parent brigade. Humphreys reports that

shortly after midday, I was ordered to form my

division in line of battle, my left joining the right of the First

Division, Major-General Birney commanding, and my right resting opposite

the left of General Caldwells's division of the Second Crops which was

massed on the crest near my place of bivouac. The line I was directed to

occupy was near the foot of the westerly slope of the ridge (Cemetery

Ridge)..., from which foot-slope the ground rose to the Emmitsburg road,

which runs on the crest of a ridge nearly parallel to the Round Top

ridge. This second ridge declines again immediately west of the road, at

the distance of 200 or 300 yards from which the edge of a wood runs

parallel to it." [71]

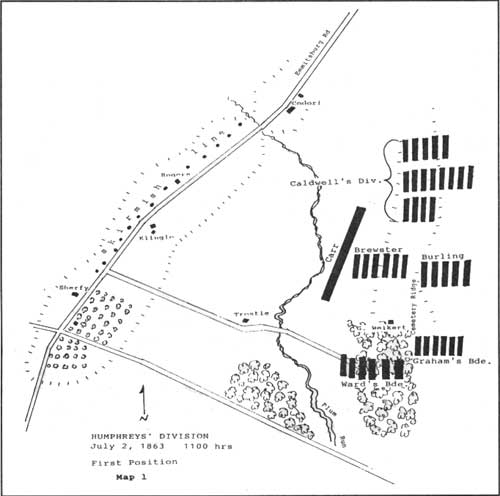

This line would be Humphreys' first position of the

day. Map 1 shows how Humphreys deployed Carr's Brigade in line of

regiments as the first line, Brewster's Brigade in line of battalions

200 yards in rear of the first line, and Burling's massed brigade as the

third line 200 yards in rear of the second line. [72]

This deployment left a gap of 500 yards from the right of Carr's brigade

to the left of Gibbon's massed division. At the time this gap did not

concern Humphreys because he considered this first position as a

temporary deployment and, besides, he could plug the gap with troops

from second and third line. [73]

(click on image for a PDF version)

Humphreys described the ground in front of this

initial position as open, but he took steps to remove obstacles by

having fences torn down. Battery K, Fourth U.S. Artillery (Seeley's) was

provided to support Humphreys from the Third Corps Artillery Brigade.

Furthermore, Humphreys ordered Colonel Brewster to strengthen the

division skirmish line along the Emmitsburg Road in front of Carr's

brigade. Brewster reports he was to hold the ground "at all

hazards" and advanced the 73rd New York to positions around the

Klingel house. [74]

|

|

Left to right: Lt. Henry C. Christiancy,

Lt. Henry H. Humphreys, General Humphreys, Capt. Carswell McClellan, and

an unrecognized officer.

|

Just as these dispositions were complete Humphreys

received an order from Sickles that would profoundly affect his ability

to hold the ground along his division's sector later that afternoon.

That order directed him to send Burling's Third Brigade to the First

Division as a reserve to Birney's badly extended division. Capt. Cavada

recorded in his diary that "Genl. H— directed me to select a

position for one of our Brigades (the 'Jersey' commdd [sic] by Col.

Burling) in rear of Birney's right and lead them to the place. I placed

the Brigade in a rocky wood of large growth about a third of a mile to

the left of the "big barn", a crumbling stone wall about 3 ft high

serving as a cover. This done I returned to our Div. now reduced to two

small Brigades." [75] One order, obediently

followed by Humphreys, reduced his combat strength by one-third!

Burling's regiments would be committed into combat in a piecemeal

fashion by Birney prompting the following comment in Burling's after

action report: "my command being now all taken from me and separated,

no two regiments being together, and being under the command of the

different brigade commanders to whom they had reported, I, with my

staff, reported to General Humphreys for instructions, remaining with

him for some time." [76] At the end of the

fighting on July 2, Burling collected what was left of his regiments and

rejoined the Second Division by 9:00 A.M. on July 3.

In the hour preceding 4:00 P.M., a rapid series of

events transpired that ultimately led to a Third Corps order for

Humphreys to advance his division to a line along the Emmitsburg Road.

Things began to heat up at 3:00 P.M. when Army Commander Meade was

apprised by his staff that one of Sickles divisions (Birney's) was

occupying a line well forward of the intended line along Cemetery Ridge

to the Round Tops. An irate General Meade decided to ride to the left

and examine Sickles advanced line for himself. Before departing

headquarters at the Leister House, Meade ordered Sykes' Fifth Corps, the

army reserve corps, to begin moving to the endangered left flank.

Furthermore, as Meade and his staff entourage rode south along Cemetery

Ridge on the way to an interview with Sickles near the Peach Orchard, he

diverted his Topological Engineer, Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren to

the summit of Little Round Top to examine the situation there. Warren's

timely action on Little Round Top made him a hero of the battle.

At the Peach Orchard salient, Meade had a spirited

conversation with Sickles just as Longstreet's pre-infantry assault fire

began to pour into the Third Corps positions. After Meade explained to

Sickles that the Peach Orchard position was neutral ground, Sickles

asked if he should begin moving his troops back. Meade replied that

"you cannot hold this position, but the enemy will not let you get

away without a fight, & and it may as well begin now as at any

time." [77] Sickles, assuming he now had Meade's

unwilling support to keep his corps on the advanced line, ordered

Humphreys' Division to move forward to the Emmitsburg Road at 4:00 P.M.

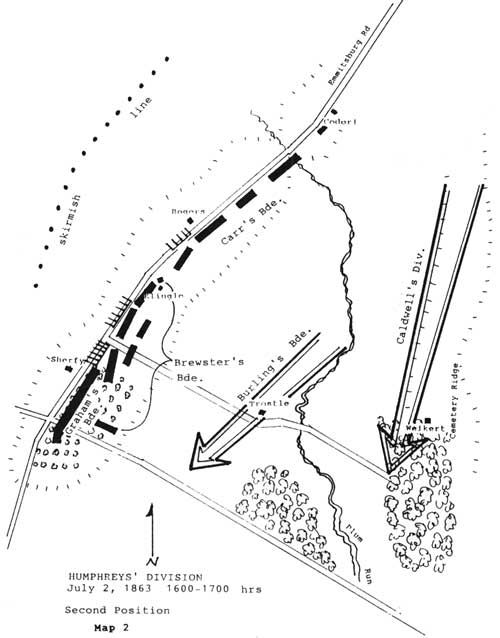

Humphreys' troop dispositions were complete.

Map 2: Humphrey's Division, July 2, 1863 1600-1700 hours (Second Position)

(click on image for a PDF version)

Humphreys' ADCs carried orders to the brigade

commanders to begin a forward movement of about 300 yards with Carr's

brigade advancing in line and Brewster's Excelsior brigade advancing in

battalions in mass. As the brigades began moving forward, Humphreys

received an order from Major Ludlow of Meade's staff

to move at once towards the Round Top and occupy

the ground there, which was vacant. Some reference was made at the time,

also, I think, to the intended occupation of that ground by the Fifth

Corps. I immediately gave the Order, by my Aides, for the Division to

move by the left flank—a movement that was made at once, and with

the simultaneousness of a single Regiment. The order given, I turned to

Colonel _______[Major Ludlow],...and requested him to ride to General

Meade and inform him that the execution of his Order, which I complying

with, would leave vacant the position my Division was ordered to occupy;

pointing out, at the same time, where the left of the Second Army Corps

was; etc. I then turned my attention to guiding my Division by the

shortest line towards the Round Top, which being done, to expedite

matters I rode full speed towards where I supposed General Meade to be,

but met Colonel ______[Major Ludlow] returning from him; who informed me

General Meade recalled his Order; and that I should occpy the position

General Sickles had directed me to take. In a second, the Division went

about face; retrod the ground, by the right flank, that they had the

moment before gone over by the left flank; and, then, moved forward to

their position along the Emmitsburg-road. The whole thing was done with

the precision of a careful exercise; the enemy's artillery giving effect

to its picturesqueness. The Division, Brigade, and Regimental flags were

flying of course. [78]

This divisional march and countermarch, so eloquently

described by Humphreys, was the movement that the rest of the army

perceived as the mass movement of the entire Third Corps to its advanced

position at 4:00 P.M. Second Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Winfield S.

Hancock, observing the spectacle of Humphreys' advance, was quick to

recognize the danger of the move and quipped to his staff "wait a

moment, you will soon see them tumbling back." [79]

Humphreys advanced the division to its second

position of the day in two lines (see Map 2). Carr's brigade, the first

line, was placed just behind the crest along which the Emmitsburg Road

runs. The right of Carr's brigade line was held by the 26th Pennsylvania

about 300 yards south of the Codori barn and he extended his remaining

regiments south along the Emmitsburg Road past the Klingel House.

Humphreys placed Seeley's Battery K, Fourth U.S Artillery equipped with

six, twelve pound smoothbore "Napoleons" to the right of the Rogers

House. During his forward deployment Humphreys sent an ADC to Third

Corps headquarters to inquire whether he should attack. The response was

for him to remain in place. [80]

Since Humphreys could not cover the entire division

sector with only Carr's brigade, he extended his line by inserting

Brewster's Second brigade regiments where needed. The 73rd New York was

relieved by Carr's men at the Kingel House and formed to the left of the

second line. The 72nd New York took position on Humphreys' left by

Trostle's lane tying in with General Graham's right near the Sherfyi

House. The 71st New York formed to the right of 72nd New York and linked

up with Carr's left regiment, the 11th New Jersey. The 74th New York was

sent to support the right of Carr's line and formed up behind the 26th

Pennsylvania. The 70th and 120th New York regiments remained on the

second line as division reserve. [81]

Between 4:00 P.M. and 5:00 P.M. Humphreys heard the

roar of musketry and cannon fire as Birney's division became decisively

engaged with Hood's Division, the first echelon of Longstreet's Corps

attack. During this time Humphreys says that the enemy made

demonstrations to his front, but did not drive in his pickets. He was

probably observing McLaws' Division, Longstreet's second echelon,

forming up prior to its attack at about 5:00 P.M. About this time the

5th New Jersey, Colonel Sewell in command, of Burling's Brigade returned

to Humphreys' control and he immediately sent it to replace the pickets

in front of Graham's Brigade which overlapped the division left flank.

Within minutes of the deployment of the 5th New Jersey Humphreys

received an urgent order from Sickles to reinforce Graham with a

regiment. Although Colonel Sewell reported that the enemy was driving in

the pickets and advancing in two lines (Barksdale's Mississippi Brigade)

Humphreys obediently stripped his division reserve and sent the 73rd New

York to Graham. Simultaneously, Humphreys sent ADC Lt. Henry Christiancy

to the Second Corps headquarters to request a reinforcing brigade from

Hancock. By this time Humphreys was well aware that Caldwell's Division

had passed behind him on its way southward to shore up General Sickles'

beleaguered left flank. [82]

Immediately to Humphreys' front, Wilcox's Alabama and

Lang's Florida Brigades of Anderson's Division (Hill's Corps) made final

preparations for an all out assault against the Enmitsburg Road.

Earlier, as he deployed along the Emmitsburg Road, Humphreys saw the

immediate need for more artillery support because his division was

receiving fire from Confederate batteries that were engaging Sickles

artillery positions in the Peach Orchard. Sending ADC Lt. Christiancy to

the rear in search of more guns, Humphreys and ADC Capt. McClellan found

a better position for Seeley's battery by moving it to the left of the

Rogers House.

Lt. Christiancy was successful in his search for more

artillery support, and in short order, Tumball's Battery (F & K,

Third U.S. Artillery) from the army artillery reserve assumed the

previous firing positions of Seeley's Battery to the right of the Rogers

House. As the enemy infantry began to advance on Humphreys' line,

Seeley's and Tumball's batteries opened fire. [83]

During this time Capt. Cavada observed that "Genl. H__ in the midst

of this hail storm moved around among the troops, and himself looked to

the fire of the batteries, (Seeley's & Turnbull's) stepping between

the guns and giving his directions, wholly intent upon the work &

heedless of the murderous missles that were felling the very gunners

around him." [84]

At this critical juncture General Sickles was

severely wounded near the Trostle farm and relinquished command to

General Birney whose own division was about to disintegrate. Birney

later claimed that he personally observed a gap between Humphreys' left

brigade (Brewster) and Graham's Brigade through which the enemy were

about to pour. Birney then ordered Humphreys to change his divisional

front to cover this threat. Humphreys later reported that the gist of

this verbal order was "to throw back my left, and form a line oblique

to and in rear of the one I then held, and was informed that the First

Division would complete the line the Round Top ridge. This I did under a

heavy fire of artillery and infantry from the enemy, who now advanced on

my whole front." [85]

Humphreys later characterized Birney's concept as

"all bosh" because in actuality there was "nobody to form the

new line but myself—Birney's troops [having] cleared out." [86] His worst fears came true when Barksdale's

Mississippi Brigade aided by Wofford's Georgians overran Graham's line

at the Peach Orchard, thereby depriving Humphreys of any support on the

left of his new oblique line. [87] Barksdale could

assail Humphreys' left while Wilcox and Lang could concentrate their

assaults on Humphreys' front and right. However, at this time Humphreys

had to direct his personal attention to his left. He considered the

division's right flank relatively secure because ADC LT Christiancy had

returned from Hancock's Corps leading two regiments of reinforcements

(the 15th Massachusetts and the 82nd New York) which were posted about

800 feet north of the division right flank near the Cordori farm.

Increased pressure from Barksdale's and Wilcox's

brigades of McLaws' Division along the picket line began to force

Sewell's 5th New Jersey back to Humphreys' main line of resistance. Capt

Cavada vividly recorded what happened next:

our left (Birney) seemed to be pressed back, and

beyond our Corps, where the 5th Corps was engaged, a terrible pounding

and crashing was going on. The breeze blowing southward carried the

heavy sulphurous smoke in clouds along the ground, at times concealing

everything from my view. Our skirmishers now began a lively popping, the

first drops of the thunder shower that was to break upon us. An aide

from Genl. Birney rode up to Genl. H_ with the report that heavy masses

of the enemy were gathering in our front & to prepare for an attack.

As everything was ready we sat quietly on our horses, dodging the shot

and shell that skimmed along. Our skirmishers were hotly engaged now and

moving back, slowly. Our own batteries silently awaiting the assault. A

copious shower of shell and canister from the enemy was followed by a

diabolical cheer and yells, and "here they come" rang along our

line. [88]

Despite intense pressure from Barksdale's

Mississippians, Humphreys and his battle staff were able with great

difficulty to form the new oblique line. Later, Humphreys modestly

confided to a friend that this movement was accomplished in "pretty

good order under heavy close fire of artillery and infantry...." [89]

In reality, however, the "close fire" was so

intense that ADC Capt. Henry Chester, seated on his horse immediately

beside his Commanding General was mortally wounded, shot through the

bowels. While Humphreys supported Chester in his saddle, he ordered his

son Henry to accompany Chester to the rear for medical aid. Henry

Humphreys turned Chester over to an orderly and quickly returned to the

firing line. [90]

Shortly after this incident Humphreys, having

supervised the formation of the oblique line, was leaving the vicinity

of the Peach Orchard, but found himself isolated about eighty yards

between his line and the enemy advancing from Warfield Ridge and up the

Emmitsburg Road. Humphreys' horse was struck by fire and pitched forward

and threw the general out of his saddle. One of the ADCs (probably his

son Henry) offered his own wounded horse to Humphreys, who declined the

offer. The ADC did retrieve the general's saddle pistol holsters but not

the saddle bags containing some important military documents. As

Humphreys and the ADC walked back to the division line, Humphreys'

orderly, Pvt. James F. Diamond, Sixth U.S. Cavalry, gave his horse to

the General. The courageous Diamond was never seen again becoming one of

the countless identified corpses on the battlefield. [91]

Humphreys nonchalantly described the situation in his

battle report by stating that "my infantry now engaged the enemy's

but my left was in the air (although I extended it as far as possible

with my Second Brigade), and, being the only troops on the field, the

enemy's whole attention was directed to my division, which was forced

back slowly, firing as they receded." [92] In

effect, Humphreys' two-brigade line would now be struck by three

Confederate brigades nearly simultaneously: from the left by Barksdale,

at his center by Wilcox, and on the right by Lang. Humphreys now

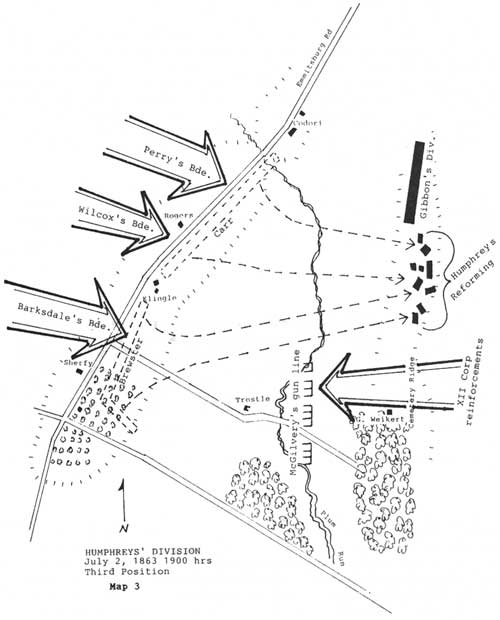

received a critical second order from one of Birney's staff officers