|

"HONOR-DUTY-COURAGE"

The 5th Army Corps During the Gettysburg Campaign

Karlton Smith

On February 8, 1880, one chapter in the history of

the Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac, came to a close. Colonel George

Sykes, former Major General of Volunteers and commander of the Fifth Corps at

Gettysburg, died at his post at Fort Brown, Texas, of cancer. He was 57.

The U. S. Congress appropriated $1,000 for the removal of his remains to

West Point. Among the subscribers to a memorial fund were Abner

Doubleday, Henry Hunt, George Gordon Meade and Henry Slocum. On a

monument of New England granite was engraved a Maltese Cross, the symbol

of the Fifth Corps, and the words "Honor-Duty-Courage"; a fitting

tribute to not only George Sykes but to the troops he had the honor to

lead at Gettysburg. [1]

George Sykes was born on October 9, 1822, at Dover,

Delaware. He graduated from West Point in 1842 and was able to count

among his classmates such future generals as William S. Rosecrans, James

Longstreet, Lafayette McLaws, and his roommate, D. H. Hill. He was

assigned to the Third U. S. Infantry and saw service in the Florida War

(1842) and in the Mexican War. He fought at the battles of Monterey,

Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, Contreras and Charubusco. Sykes was brevetted a

captain for gallant and meritorious conduct in the battle of Cerro

Gordo. [2]

Known as "Tardy George" to his West Point classmates,

it has been noted that this was more of a mental tardiness than a

physical one. D. H. Hill, a future Confederate general and Sykes'

roommate, stated that Sykes was "a man admired by all for his honor,

courage, and frankness, and peculiarly endeared to me by his social

qualities." [3]

On May 14, 1861, Sykes was promoted to major of the

Fourteenth U. S. Infantry and led the battalion of Regulars (eight

companies from three regiments) at the battle of First Bull Run. As more

regular army units reported to Washington, Sykes' command grew into two

brigades of ten regiments and became known as the Regular Division. On

September 28, 1861, Sykes was appointed a brigadier general of

volunteers. [4]

On March 8, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln ordered

the units of the Army of the Potomac, under Major General George B.

McClellan, to be organized into four army corps. A fifth corps was to be

commanded by Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, but this corps never

operated with the Army of the Potomac and was disbanded on April 4,

1862, and merged with the Department of the Shenandoah. Sykes'

command, known as the Infantry Reserve, was not

initially assigned to a corps. [5]

On May 18, 1862, General McClellan authorized the

creation of the Fifth Provisional Corps. This order was confirmed by the

War Department when the term "Provisional" was dropped. The Fifth Corps,

under Major General Fitz-John Porter, consisted of two divisions of

three brigades each. The First Division consisted of Porter's old

division taken from the Third Corps. The Second Division, under George

Sykes, contained two brigades of regular infantry and one brigade of

volunteer troops commanded by Colonel Gouverneur K. Warren. The Second

Division artillery, consisting of two batteries, was commanded by

Captain Stephen H. Weed. [6]

At this time, there were several officers already

serving with the Corps, besides George Sykes, who later played key roles

in the history of the Fifth Corps at Gettysburg.

The Second Brigade of the First Division was

commanded by Charles Griffin. Griffin, born in Granville, Ohio, on

December 18, 1825, was an 1847 graduate of West Point. He was assigned

to the Fourth U. S. Artillery and took part in the march to Pueblo,

Mexico, but missed seeing action due to illness. He served on garrison

and frontier duty with the Second Artillery until assigned as an

Assistant Instructor of Artillery at West Point in September, 1860. He

was directed to organize a light battery company from the enlisted

personnel assigned to the Academy. At first known as the West Point

Battery, it was redesignated as Battery D, Fifth U. S. Artillery and was

led by Griffin at the First Battle of Bull Run. Griffin was appointed a

brigadier general of volunteers on June 9, 1862. Griffin was described

as being "arrogant, self-confident, often perilously near to

insubordinate" and "more considerate of his subordinates than of his

superiors," but "stern in his sense of duty." [8]

The 18th Massachusetts of Griffin's brigade was

commanded by 61-year old Colonel James Barnes. Barnes, an 1829 graduate

of West Point (along with Robert B. Lee) stayed at the Academy as an

Assistant Teacher of French until August of 1830. He was stationed at

Charleston, South Carolina, with the Fourth U. S. Artillery, during the

Nullification Crises of 1832. He returned to West Point as an Assistant

Instructor of Infantry Tactics. He resigned in 1836 to begin a

successful career as an engineer and built several railroads between

1852 and 1857. [9]

The command of the Third Brigade, First Division went

to Brigadier General Daniel Butterfield. Born in Utica, New York, in

1831, he graduated from Union College in 1849. He served as

superintendent of the eastern division of the American Express Company.

He joined the 71st New York Militia as a captain and later became

colonel of the 12th New York. On September 7, 1861, he was appointed a

brigadier general of volunteers and assigned to the command of the Third

Brigade. [10]

Colonel Gouverneur K. Warren, Fifth New York,

commanded the Third Brigade in the Second Division. Warren, born at Cold

Spring, New York, across the river from the academy, graduated from West

Point in 1850 and was assigned to the Topographical Engineers. His major

work, with Captain Andrew A. Humphreys, was in compiling the general map

and reports of the Pacific Railroad Explorations in 1854. He was also

involved in preparing maps and reports on both the Dakota and Nebraska

Territories. He served as an assistant of mathematics at West Point from

1859 to 1861. On May 14, 1861 he was named lieutenant colonel of the 5th

New York, and on August 31 was named colonel of the regiment. He was

placed in command of the Third Brigade on May 24, 1862. [11]

Stephen H. Weed, born in 1831 at Potsdam, New York,

was an 1854 graduate of West Point. Other, soon to be well-known

graduates, included Oliver O. Howard and J.E.B. Stuart. Weed, assigned

to the Fourth U. S. Artillery, fought against the Seminole Indians in

Florida (1858) and took part in the Utah Expedition (1858-1861). He was

promoted to captain in the Fifth U. S. Artillery on May 14, 1861. [12]

No history of the Fifth Corps, no matter how brief,

would be complete without Frederick T. Locke. At the age of 34, Locke

had enrolled on April 19, 1861 in the 12th New York Militia for three

months. He was mustered in as Adjutant, May 2, 1861, and detached as

brigade major and assistant adjutant-general of the 8th Brigade at

Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), on July 14. He was mustered

out with his regiment on August 5. Locke was reappointed as an assistant

adjutant-general with the rank of captain and assigned to duty as the

assistant adjutant-general, Fifth Corps, with the temporary rank of

lieutenant colonel on August 20, 1862. Colonel Locke held this position

with the Fifth Corps until he was relieved on August 1, 1865, and

mustered out as a captain on September 19, 1865. He was awarded the

brevet of colonel of volunteers (August 1, 1864) for brave, constant,

and efficient service in the battles and marches of the campaign and

brevetted a brigadier general of volunteers (to date from April 1, 1865)

Frederick Locke for gallant and meritorious service at the battle of

Five Forks, Virginia. [13]

On June 12 and 13, 1862, George McCall's division of

Pennsylvania Reserves (9500 strong) was temporarily detached from the

First Corps, Department of the Rappahannock, and on June 18 was assigned

as the Third Division of the Fifth Corps. Two of McCall's brigade

commanders were John F. Reynolds and George Gordon Meade. On May 31,

prior to McCall's joining, the Fifth Corps reported 17,546 present for

duty. [14]

During the Seven Days' battles, June 26 to July 1,

the Fifth Corps suffered 7,601 casualties, accounting for half the total

casualties in the Army of the Potomac. The Pennsylvania Reserves were

detached and returned to the First Corps about August 20. At Second Bull

Run, Griffin's brigade was stationed at Centerville and was not present

on the battlefield. The Fifth Corps, which numbered about 6500 on the

field, lost an additional 2000. [15]

On September 26, 1892, Daniel Butterfield received a

Medal of Honor for action at Gaines' Mill on June 27, 1862, for

distinguished gallantry where he "seized the colors of the 83d

Pennsylvania Infantry Volunteers at a critical moment, and, under a

galling fire of the enemy encouraged the depleted ranks to renewed

exertion." Also at Gaines' Mills, Colonel Warren was wounded and Colonel

J. W. McLane, of the 83rd Pennsylvania, was killed in action. McLane was

succeeded in command by Lieutenant Colonel Strong Vincent who had been

stricken with malaria before the battle and did not rejoin the regiment

until Fredericksburg. [16]

At Antietam on September 17, 1862, the Fifth Corps

was in reserve and only lightly engaged until late in the day. The total

loss to the Corps during the Maryland Campaign was 472 casualties. On

September 18, a new Third Division was added to the Corps. This

division, made up mostly of nine-month units, was commanded by Brigadier

General Andrew A. Humphreys. [17]

Humphreys, born in 1810 in Philadelphia, graduated

from West Point in 1831. Although initially assigned to the Second U. S.

Artillery, Humphreys spent most of his career with the engineers. He

resigned in 1836 and served as a civil engineer for the U. S. Army. In

1838 he was reappointed to the Topographical Engineers. In 1854 he was

directed by the Secretary of War to take charge of the surveys, ordered

by Congress, "to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for

a railway from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean." He served as

Chief Topographical Engineer, Army of the Potomac, March to August 1862,

and was appointed a brigadier general of volunteers on April 28, 1862.

[18]

By Presidential Order (September 5, 1862), Major

General Fitz-John Porter was relieved of command of the Fifth Corps on

November 5 and Charles Griffin was relieved of command of the Second

Brigade, First Division "until the charges against them can be

investigated by a court of inquiry." The charges stemmed from their

reported actions, or inactions, at the battle of Second Bull Run and

were preferred by Major General John Pope. Porter was court-martialed,

found guilty and cashiered from the U. S. Army. Although not "tried and

acquitted," Griffin was restored to duty. Butterfield, Griffin, Locke,

and Sykes were all called to give testimony during Porter's

court-martial. [19]

On November 12, Major General Joseph Hooker assumed

command of the Fifth Corps. Four days later Hooker was placed in command

of the new Center Grand Division and Daniel Butterfield assumed command

of the Corps. The Fifth Corps crossed the Rappahannock River at

Fredericksburg at about 3:00 p.m. on December 13, preparatory to

attacking the enemy's works. However, "the attack was made against

positions so advantageous and strong to the enemy that it failed." The

troops held some advance positions until December 15 and 16, sustaining

over 2000 casualties. Warren had been given the duty "of arranging a

line of earthwork defenses,...battery epaulements and rifle-pits,

connecting with brick houses and walls, intended to be loop-holed, and

barracading all the streets..." [20]

On November 17, Butterfield recommended Stephen H.

Weed and Strong Vincent for promotion to brigadier general of volunteers

"for gallantry and good services in the attack of December 13."

Butterfield added that Weed "seeks the post of honor and danger on the

field" and by his "judgement, energy, and bravery,...had proven his

capacity for the promotion." Vincent had long served under Butterfield

and "has by gallantry and devotion to duty richly merited promotion."

[21]

In the weeks following Fredericksburg several changes

took place in the command structure of the Fifth Corps. On December 24,

Butterfield was relieved of corps command by Major General George Gordon

Meade and on January 29, 1863, Butterfield assumed the duties of Chief

of Staff, Army of the Potomac, under Major General Joseph Hooker. Meade

also commanded the Center Grand Division until February 5, when the

grand divisions were abolished. During this time, George Sykes had

assumed temporary command of the Corps. On February 5, General Warren

was named Chief Topographical Engineer for the Army of the Potomac and

Colonel Patrick O'Rorke, 140th New York, assumed command of the Third

Brigade, Second Division. On April 19, Brigadier General Romeyn B. Ayres

was relieved from command of the Artillery Reserve (which he had

commanded for six days) and assumed command of the First Brigade, Second

Division. [22]

Romeyn B. Ayres, born in Montgomery County, New York,

in 1825, graduated from West Point in 1847 (in the same class as Charles

Griffin). He served with the Fifth U. S. Artillery at Pueblo and the

City of Mexico. During the pre-war period he performed routine garrison

duties at various posts including the Artillery School of Practice at

Fort Monroe, Virginia. He was promoted to captain in the Fifth U. S.

Artillery on May 14, 1861, and served as Chief of Artillery of Smith's

Division (October 1861 to November 1862) and as Chief of Artillery of

the Sixth Corps. Ayres was "a tall man of distinguished presence, erect

and soldierly," "somewhat vain of his appearance and meticulous as to

dress," but nonetheless, an "energitic, determined, hard-fighting

commander." Since the War Department had decided that the army had

enough high ranking artillery officers, the only way for an artillerist,

to gain high rank was to transfer to another branch. As a result, the

artillery lost many fine officers to Romeyn B. Ayres the infantry. [23]

On March 21, 1863, a circular by General Hooker

announced the creation of corps badges. This was for "the purpose of

ready recognition of corps and divisions in this army and to prevent

injustice by reports of straggling and misconduct through mistake as to

its organization." Each division of a corps was to be designated by a

different color: red for the First, white for the Second, and blue for

the Third. The Fifth Corps was to be represented by a Maltese Cross. [24]

On May 1, 1863, Sykes' Division was the first to meet

Confederate resistance during the Chancellorsville Campaign. When Sykes

found the enemy in force and threatening to outflank him, he reported

this "to the major-general commanding the army, and by him was ordered

to withdraw." The rest of the Fifth Corps was also ordered to assume the

defensive. In his official report, Meade noted that Sykes' advance on

May 1 "was a brilliant operation, adding to the already well-earned

reputation of that gallant body of soldiers." He also reported that

Griffin's Division "proved by their steadiness and coolness that this

division only wanted a fair opportunity to show that the laurels

acquired on so many previous fields were still fresh and undimmed."

Because they were lightly engaged, the Fifth Corps only suffered about

700 casualties. [25]

By the end of May, the Corps lost, by muster-out,

eleven regiments. Six of these regiments came from Humphreys Third

Division. The remaining two regiments of the division (91st and 155th

Pennsylvania) were transferred to the Third Brigade, Second Division (to

replace the two regiments this brigade lost by muster-out), and the

Third Division was discontinued. General Humphreys was transferred to

the command of the Second Division, Third Corps. Charles Griffin went on

sick leave beginning May 15, and James Barnes assumed temporary command

of the First Division. On June 6, Captain Stephen H. Weed, commanding

the Second Division Artillery Brigade, was promoted to brigadier general

of volunteers and on June 13 relieved Colonel O'Rorke as commander of

the Third Brigade, Second Division. [26]

At the start of the Gettysburg Campaign, the Fifth

Corps would be composed of battle-tested leaders and veteran soldiers.

Many of these men had been associated with the Corps from the beginning.

It was time to see if the honor, duty and courage of the Maltese Cross

could stop General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia.

By May 25, the Fifth Corps was encamped along the

Rappahannock River, near Fredericksburg, from Potomac Creek, near High

Bridge, to the head of Clairburn Run, near the Telegraph Road where the

encampments of the First Division were also located. At 10:45 a.m. Meade

was ordered to send a division to relieve the cavalry pickets holding

Banks', Richards', Kelly's, and United States Fords and to "throw up

such defenses as will repel any attempt of the enemy to effect a

crossing" at the fords. [27]

Meade entrusted this task to the First Division,

under James Barnes. Barnes was to move without delay and take a position

covering the fords on the Rappahannock River and to make "such

dispositions as will enable you to check, and, if practicable, prevent

the crossing of that river by any body of the enemy's troops." Meade

gave Barnes very specific instructions on where and how to post his

division. He also instructed Barnes to take entrenching tools from the

supply wagons and direct his subordinate officers "immediately prepare

defenses, such as rifle-pits and epaulements for batteries, and to every

disposition to check, retard, and prevent the crossing of the river."

[28]

After completing an inspection of his lines on May

31, Meade reported that the river was very low and could be crossed at

numerous places by small bodies of troops. Barnes had to weaken his

forces at the main crossing points in order to try to cover all the

possible crossings. Meade also felt that Lee could not be stopped if he

was determined to force a passage. In a second message to headquarters,

Meade requested authority to move Sykes' division, plus three batteries

of 12-pound Napoleons, to help guard the fords. It is not clear why

Meade needed permission to move his Second Division, but headquarters

deemed it not advisible to move Sykes at this time. The difficulty of

supplying the artillery also made it "inexpedient" to send it to the

fords. Headquarters further "presumed that the forces now on duty will

be vigilant in the performance of their duties. It will be active in

obtaining and sending on information, so that any movements of the enemy

may be promptly reported to headquarters." [29]

While Meade and company were busy on the Rappahannock

River, events were transpiring on the Potomac River at Alexandria,

Virginia, that would eventually have an impact on the Fifth Corps during

the campaign. On June 1, Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford assumed

command of the First and Third Brigades of the Pennsylvania Reserves

which were posted at Fairfax Station and Upton's Hill. [30]

Samuel W. Crawford, born in 1829, was the only Civil

War general born in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, only about 25 miles

west of Gettysburg. After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania

in 1846, he attended the university's medical school and received his

degree in 1850. On March 10, 1851, Crawford accepted an appointment as

an assistant surgeon in the army and served at various frontier posts

until 1860 when he was stationed at Fort Moultre in Charleston, South

Carolina. After Fort Sumter, Crawford was appointed a major in the 14th

U. S. Infantry (May 14, 1861). Promoted to brigadier general of

volunteers on April 25, 1862, he saw action in the Shenandoah Valley and

commanded the First Brigade, First Division, Twelfth Corps at Antietam.

Crawford's commander, Alpheus S. Williams, reported that Crawford had

been wounded "but not so severely as to oblige him to leave the field."

However, shorty after dark Crawford, "exhausted from the loss of blood

and state of my wound," reported his condition and left the field. His

wound kept him from the field until assigned to the Pennsylvania

Reserves. [31]

On June 4, Sykes was ordered to move, without delay,

to positions on the Rappahannock. He was to post one brigade at Banks'

Ford and one brigade at United States Ford. Sykes, with his

subordinates, was directed to arrange "a plan of operations in case the

enemy should force a passage at any point" and to have his troops

"prepared for immediate movement." [32]

The pace of activity along the Rappahannock began to

increase as the month of June advanced. On June 6, Colonel Strong

Vincent reported strong enemy pickets at Kemper's Ford, and at Ellis'

Ford the enemy had made no attempt to conceal his movements. Meade was

asked if he could "feel the enemy, and cause him to develop his strength

and position at various points along" his front. Sykes objected to this

move on the grounds that Banks' Ford was exceedingly difficult and the

nature of the ground was such that once a Union force was across the

river it "could not get back if the enemy chose to prevent it." While at

United States Ford the enemy camps were so far back that it would be

difficult to determine their strength. Nonetheless, the next day Meade

was directed to feel the enemy strength at Banks' Ford without bringing

on a fight. [33]

At 1:00 a.m. on June 9, Meade expressed satisfaction

at the arrangements for cooperation between Barnes and the Cavalry

Corps. Barnes was also told that instead of having to send in reports

every three or four hours he could do so about every six hours. But that

"Very important information will of course be sent in as soon as

received." At 7:00 p.m. Meade started to direct Barnes to send 1000 men

to the cavalry's support at Brandy Station when a message from

headquarters suspended the movement. Meade did regret having to call

Barnes' attention "to the necessity of keeping me promptly and

frequently advised of what is transpiring in your front." Meade noted

that the last dispatch from Barnes at Kelly's Ford had been sent at 7:00

a.m. and that a fast horse could cover the distance in two hours. Meade

was also concerned about late reports from Colonel Jacob Sweitzer.

Sweitzer, who had returned from helping the cavalry at 5:00 p.m. on June

9, did not report his presence to Meade until 1:00 p.m., June 10. [34]

On June 13, the race to find Lee and bring him to

battle began. Sykes and Barnes were ordered in be in readiness "to move

tonight or early to-morrow morning." Sykes was told to concentrate his

division, including the trains and batteries, at Hartwood Church and as

soon as his pickets were relieved, he was to "proceed as rapidly as

possible to Warrenton Junction." The Fifth Corps was to rendezvous at

Manassas Junction with the First, Third, and Eleventh Corps. By the next

day, June 14, the Third and Fifth Corps were at Catlett's Station. [35]

On June 21, Barnes' Division was again sent to

cooperate with the Cavalry Corps. The Second Division was stationed at

Aldie, while the First Division moved to Middleburg where the Third

Brigade, under Colonel Strong Vincent, was sent to support Brigadier

General David M. Gregg's Cavalry Division. Vincent's Brigade aided the

cavalry in the engagements at Upperville and Goose Greek and was

relieved by Colonel William S. Tilton's First Brigade. [36]

Twice during this time, the Fifth Corps had an

opportunity to capture the Confederate cavalry leader John S. Mosby. The

first attempt, on June 22, under Captain W. H. Brown, 14th U. S.

Infantry, failed partly because of "defective ammunition" due to rain in

the morning. Ayres, the brigade commander, expressed disappointment with

the results, while Sykes, somewhat more critical, believed that Brown

"should have had the foresight to see that his infantry were efficient

and their arms in firing condition before leaving camp,..." A second

attempt on June 24 also misfired when Mosby failed to show up as

expected. [37]

The services of Crawford's Pennsylvania Reserves were

being requested by both Meade and Major General John F. Reynolds. Both

of these officers had held commands with the Reserves during the early

part of the war and knew their value as soldiers from first-hand

experience. However, Major General Samuel P. Heintzelman, commanding the

defenses of Washington, considered that the Reserves properly belonged

to him. Nonetheless, on June 23, Crawford was ordered to place his

command "in readiness to move at very short notice." Two days later he

was ordered to march with his command to Edwards Ferry and, if possible,

to cross the Potomac River. Major General Henry Halleck, the army's

Chief of Staff, however, had to verify that the Second Brigade of

Reserves formed no part of Crawford's command. [38]

At 4:00 a.m. on June 25 the Fifth Corps, with the

Artillery Reserve, crossed Goose Creek at Carter's Mill on its way to

Leesburg, Virginia. It crossed the Potomac River at the upper pontoon

bridge, located between Edwards Ferry and the mouth of the Monocacy

River, and followed the river road towards Frederick, Maryland. These

orders, issued on June 25, had been sent by General John F. Reynolds via

his cavalry escort. They were to have been sent by signal but the signal

camps had already been broken up. [39]

At 9:25 a.m., June 27, Crawford notified Meade that

his troops were crossing the Potomac at Edwards Ferry and would join

Meade that night. Crawford was having some difficulty on the road

because it was "encumbered by trains of Third Corps." This would not be

the last time that the Fifth Corps had trouble with the Third Corps

during the campaign. [40]

This march of the Fifth Corps, from the Rappahannock

River to Frederick, had not been an easy one. Lieutenant James P. Pratt,

11th U. S. Infantry, wrote to his parents on June 15, telling them that

his feet "are one complete blister. It was with the greatest difficulty

I kept along, but I was determined to do it. I don't think I could march

another hour though." On June 27, Pratt wrote that both his shoes and

stockings had worn out; his blistering feet unprotected. He did predict

that "we shall probably came upon the Rebels by to-morrow evening or

next day." [41]

Major changes in the command structure of the Fifth

Corps took place on June 28 at Frederick. Major General Hooker was

relieved of command of the Army of the Potomac and replaced by Major

General George G. Meade. Sykes, as the senior division commander,

assumed command of the Corps. Ayres assumed command of the Second

Division and Colonel Hannibal Day, sent from Washington, assumed command

of the First Brigade, Second Division.

On June 29, the march north resumed with the Fifth

Corps marching 15 miles from Frederick to Liberty. The next day Sykes

advised Ayres that a "long march is before us, and every effort must be

made to keep the command together and well closed up, and the enemy is

not far from us." "Strong exertions," Sykes stated, "must be made to

prevent straggling and to make the men keep in ranks." The march that

day covered 23 miles to Union Mills. [42]

At 6:30 p.m., June 30, Sykes reported that the First

and Second Divisions were at Union Mills and that the artillery was soon

expected. The Third Division had been directed to march until dark and

encamp between Frizellburg and Union Mills. Sykes stated that Crawford

"must have marched to-day in the neighborhood of 25 miles. I have not

had the corps concentrated since leaving Fredericksburg. My troops are

foot-sore and tired." Crawford's command, having spent several months in

the Washington defenses, were still trying to get their "campaign legs"

back in shape. [43]

On July 1, the Fifth Corps marched 11 miles to

Hanover, Pennsylvania. At 7:00 p.m. orders were received to march

towards Gettysburg. Colonel Jacob Sweitzer's Brigade, after being

ordered out, had an "exciting little run" with Colonel Strong Vincent's

Brigade, to see who would get back into the road first and lead the

division. Vincent won the race. Sweitzer not only reported having heard

a rumor that Major General George B. McClellan was in Gettysburg to take

command of the army but had met a citizen who had "seen the Genl.

there." The head of the Corps would reach Bonaughtown, on the Hanover

Road, by midnight after a march that day of 20 miles. Sykes reported

that he would "resume my march at 4 a.m. Crawford's division had not

reached Hanover at the hour I left there." The Pennsylvania Reserves

were still having a hard time keeping up. [44]

The Fifth Corps resumed its march on the Hanover Road

at about 3:00 a.m. After marching about 2 miles they turned left

(probably at the E. Deardorff farm on Brinkerhoff Ridge) toward the

Baltimore Pike and arrived in the area of Wolf's Hill by 8:00 a.m. (the

Third Division arrived about noon). At first stationed on the north side

of the Baltimore Pike, to support a proposed counterattack, the Corps

was moved to the south side in support of the Twelfth Corps on Culp's

Hill. The Corps took position between Rock Creek and the Granite

Schoolhouse Lane, near Power's Hill. In this position Sykes was directed

"to support the Third Corps,...,with a brigade, should it be required."

Sykes sent Colonel Locke, his assistant adjutant-general, and Captain

John W. Williams, aide-de-camp, to Major General Daniel Sickles,

commanding Third Corps, "to see where the left of the 3d corps would

rest" as Weed's Brigade was to be sent to the support of the First

Division (Brigadier General David B. Birney), Third Corps. According to

Captain Alexander Moore, of Sickles' staff, he was sent at 2:10 p.m. "to

request Sykes to send a brigade to support Birney." Sykes, according to

Moore, replied that he "would rather not send a brigade at once, but

would do so if any necessity arose"; or if he were notified by either

General Birney or Brigadier General J. H. Hobart Ward, of Birney's

Second Brigade. [45]

General Meade ordered a meeting of all his corps

commanders for 3:00 p.m. at his headquarters. The exact timing of events

at this meeting varies with the participants, but they did take place in

a short space of time. General Warren, now serving as Chief Engineer of

the Army of the Potomac, received a report that General Sickles and his

Third Corps were "not in the proper position." When cannonading was

heard in the direction of the Third Corps, Sickles had not yet reached

headquarters. Meade, not wasting any time, ordered Warren to the left to

survey the situation and ordered Sykes to march the Fifth Corps to the

left as quickly as possible and to "hold it at all hazards." Meade,

reportedly, also told Sykes that he would join him and see to the corps'

posting. Sykes believed this order "relieved my troops from any call

from the commander of the Third Corps." It does not appear, however,

that this impression was passed on to General Weed, as events will soon

show. [46]

Sykes, who had apparently left most of his staff and

the Corps flag near Power's Hill, directed Lieutenant George T. Ingham,

aide-de-camp, to instruct Captain William Jay, aide de-camp, to lead the

Corps toward the left. The rest of the staff was to wait on Power's Hill

for Sykes' return. Sykes, with one orderly, rode to the left to select

positions for his troops. He did not go directly to Little Round Top but

went, instead, to the area of Rose's Woods, near what became known as

the Stony Hill, to confer with General Birney. As a professional

soldier, Sykes could not have liked what he saw. The Third Corps,

instead of being on Cemetery Ridge with its left on Little Round Top,

had been advanced three-quarters of a mile west to the Emmitsburg Road

and the Peach Orchard. A one-half mile gap existed in the Third Corps

line from the south edge of the Peach Orchard to the Stony Hill with the

left flank of the Corps in and near Devil's Den. Sykes found a battery

(probably Captain James Smith's 4th New York Light) on the outer edge of

Birney's line without adequate support. Sykes, who now realized he would

not be able to fight his corps as a unit, suggested that if Birney

closed his division on the battery, Sykes would fill the gap with troops

from his corps. [47]

Meanwhile, Warren had arrived on Little Round Top and

found the hill bare of troops except for a detachment from the Signal

Corps. Warren sent a message to Meade requesting a division be sent to

the hill and also sent Lieutenant Ranald S. Mackenzie to request troops

from Sickles. Sickles refused the request stating "that his whole

command was necessary to defend his front, or words to that effect."

Approaching the field at about this time (4:30) was the First Division,

Fifth Corps. [48]

|

|

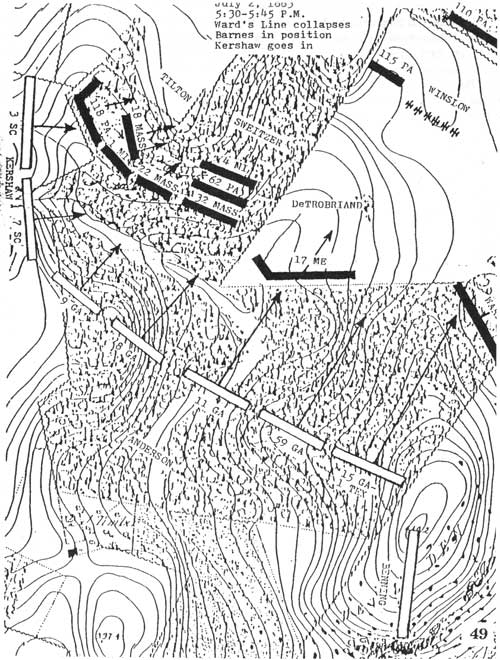

July 2, 1863 - 5:30-5:45 P.M. Ward's

Line collapses, Barnes in position, Kershaw goes in (click on image

for a PDF version)

|

The First Division (3417 men) had started its move

from the Power's Hill area at about 3:30 with Vincent's Brigade in the

lead, followed by Sweitzer and Tilton and three batteries: Battery D,

5th U. S., under Lieutenant Charles Hazlett; Third Battery (C),

Massachusetts Light, under Lieutenant Aaron Walcott; and Battery I, 5th

U. S., under Lieutenant Malborne Watson. (The two other batteries,

Battery L, 1st Ohio, Captain Frank Gibbs and Battery C, 1st New York,

Captain Almont Barnes, followed the Second Division.) The division had

about a two mile march via the Granite Schoolhouse Lane to the Taneytown

Road to the Wheatfield Road. As the head of the column entered the

Wheatfield, Warren found Sykes and Barnes on the Stony Hill and

requested assistance in holding Little Round Top. Sykes, also realizing

the importance of the hill, directed Barnes to supply a brigade. Barnes

"immediately directed Colonel Vincent,...,to proceed to that point with

his brigade." Sykes personally posted Sweitzer and Tilton (with 077 men)

on the Stony Hill and then rode back to the Taneytown Road to bring up

more troops. [49]

Captain Augustus P. Martin, commanding the Corps

Artillery Brigade, also arrived near the Stony Hill. Martin had

originally enlisted on April 20, 1861, in the 1st Massachusetts

Artillery Militia for three months. He was mustered out as a sergeant on

August 2, 1861. He was mustered back into service as a First Lieutenant

on September 5, 1861, with Battery C, 3rd Massachusetts, for three

years, and was promoted to captain on November 28. In October 1862,

General Porter recommended Martin for promotion to field grade officer.

Porter felt Martin had "earned the promotion suggested by gallant action

and by his general efficiency in all duties heretofore intrusted to his

charge." [50]

Martin ordered Lieutenant Charles Hazlett to post his

battery, formerly Griffin's Battery, on Little Round Top. Martin ordered

Lieutenant Aaron F. Walcott and Lieutenant Malborne Watson to post their

batteries in the rear of Barnes' division and await further orders.

Martin then accompanied Hazlett to Little Round Top to reconnoiter for

the best position to locate the battery. By the time Martin returned to

the Stony Hill, both Walcott and Watson had been ordered away by staff

officers from the Third Corps, who claimed to have "orders to take away

any batteries..., no matter where they belonged." [51]

Hazlett's Battery appears to have followed the same

route as Vincent's Brigade (see next paragraph) as one report states

that they went up at a trot. At some point, the guns had to be taken

onto the summit by hand, maybe with the help of some stragglers. On the

shelf, near the monument to the 140th New York, Hazlett was able to

place four guns. He may have succeeded in getting all six guns up but

there was room for only four guns so two were taken back down. Once in

position, Hazlett started "sending shells down the mountainside towards

Devil's Den." [52]

Vincent's brigade (1336 strong) marched from the

Wheatfield to the north slope of Little Round Top following the

Wheatfield Road and, probably utilizing an old logging road, moved along

the east side of the hill to the south slope. Vincent preceeded his

column to conduct a personal reconnaissance. He placed his brigade with

the 44th New York on the right, followed by the 83rd Pennsylvania, the

20th Maine, and the 16th Michigan on the left flank. The 16th Michigan

had just sent out skirmishers when it was ordered to the right of the

44th New York, probably because Vincent believed that would be the point

of greatest danger and not the left flank. Colonel N. E. Welch reported

that before the move was completed "we were under a heavy fire of the

enemy's infantry. We succeded, however, in securing our places after

some loss." The brigade was no sooner in position, then the 44th New

York and 83rd Pennsylvania were hit by Confederate attacks. The two

regiments returned fire at a range of forty yards. Colone James C. Rice,

44th New York, reported that the Confederates "tried for an hour to

break the lines of the 44th New York and 83rd Pennsylvania, charging

again and again within a few yards of those unflinching troops." While

the center of the brigade line held firm, Confederate troops were

beginning to threaten Vincent's flanks at the 20th Maine and the 16th

Michigan. [53]

The fighting done by Colonel Joshua Chamberlain and

the men of the 20th Maine, on Vincent's left flank, has been well

documented. After being struck several times by the 15th Alabama, and

after the left flank of the Maine line had been thrown back, the

regiment mounted a make-shift counterattack. This attack came as the

Alabama troops were falling back and just before the arrival of fresh

troops from the Pennsylvania Reserves (see below). [54]

Colonel Welch reported that he was under heavy fire

(probably from the 4th and 5th Texas and 48th Alabama) for about a half

an hour "when some one", he thought either Sykes or Weed, although this

is doubtful, ordered him to fall back to a more defensible position. He

stated that these "orders" were not obeyed except by individuals and a

Lieutenant Kydd who took the regimental colors back to the summit.

However, the right two companies started to fall back while the rest of

the regiment "was thrown into confusion." Confederates started to lap

around the right flank of the 16th Michigan when Colonel Patrick O'Rorke

and the 140th New York appeared at the crest and launched a savage

counterattack. The attack succeeded in reestablishing the right flank of

the 16th Michigan and repulsing the Confederate attack but at the price

of O'Rorke's life. The 44th New York may have also fired obliquely at

the same time. It was while trying to rally the 16th Michigan that

Colonel Vincent was mortally wounded. [55]

During the initial attack against Vincent's line,

Warren was trying to get more troops to the hill. He spotted Weed's

Third Brigade, Second Division, part of Warren's old brigade, moving

west on the Wheatfield Road to join Sickles, Weed's Brigade (1484

strong) had, reportedly, been led to this arena by Captain Moore of

Sickles' staff, the same Captain Moore who at 2:10 p.m. had requested a

brigade from Sykes. Weed, and Captain Moore, had ridden ahead to confer

with Sickles at the Trostle Farm. It was "at this point the leading

regiment", the 140th New York under Colonel Patrick O'Rorke, was

redirected to Little Round Top by Warren. The rest of the brigade formed

line "in a narow valley", Plum Run, to support a portion of the Third

Corps and Watson's Battery. [56]

By this time Sykes was on the north slope of Little

Round Top after leading up "the remaining troops of the corps." He sent

a staff officer to find out why Weed had moved "away from the height

where it had been stationed, and where its presence was vital." Weed was

directed to retrace his steps, which he did at the double-quick. Sykes

gave instructions to Captain Jay for the posting of the Second and First

Brigades of the Second Division. Sykes also spoke briefly with Warren

before Warren left the hill with a slight wound. Sykes then proceeded up

the back side of the hill to Hazlett's position. [57]

Sykes' criticism of Weed may have been overly harsh.

Earlier in the day Meade had requested Sykes to have a brigade standing

by to help Sickles, and Sykes had designated Weed's Brigade for the

assignment, an order which most likely went through Romeyn B. Ayres,

Weed's division commander. As stated previously, when Meade ordered the

Fifth Corps to the left, Sykes believed that this relieved his troops

from any call by the Third Corps. But this change of orders does not

appear to have been transmitted to either Ayres or Weed. Both of these

regular army officers were too good to have deliberately disobeyed a

direct order from Sykes not to aid Sickles.

While fighting was occurring on Little Round Top it

was also breaking out on other parts of the Fifth Corps line. When

Vincent moved to Little Round Top, Barnes' other two brigades, under

Colonel Jacob B. Sweitzer and Colonel William Tilton, advanced through

the Wheatfield into Rose's Woods and onto the Stony Hill. They were

placed to the right and rear of the Third Brigade of Birney's division.

Sweitzer reported that his brigade was placed in a woods that fronted an

open field. The brigade fronted to the west towards the Peach Orchard.

As this threw the left regiment, 32nd Massachusetts, beyond the woods

into low, cleared ground, Sweitzer ordered it to change front to the

rear, placing it on more elevated ground, facing towards the south. This

placed the 32nd Massachusetts at a right angle to the Jacob Sweitzer

62nd Pennsylvania on its right. Sweitzer later stated that both Sykes

and Barnes were present "when this position was assigned me and the

point at which my right was to rest was designated." [58]

Tilton's Brigade was posted just to the right of

Sweitzer's (the 32nd Massachusetts next to the 22nd Massachusetts). The

18th Massachusetts, not having enough room in the front line, was

stationed in the rear of the 1st Michigan. As there was no infantry on

Tilton's right, he refused the right wing of the 118th Pennsylvania to

form a crotchet. [59]

Barnes was most concerned about his right. The only

unit to his immediate right was the 9th Massachusetts Artillery

(Bigelow's Battery) along the Wheatfield Road. The closest infantry

support on his right was the First Brigade, First Division, Third Corps

at the Peach Orchard about one-quarter mile away. The Third Brigade,

First Division, Third Corps was stationed on Barnes' left along with

Battery D, First New York Light. When Barnes stated his concerns to

Sykes, he remarked that some Third Corps troops, whom Barnes had passed

and were lying in his rear, were to be removed. What exactly Sykes meant

by this is unclear. Sykes then left Barnes to attend to affairs on

Little Round Top. [60]

Almost as soon as Sykes left, fighting erupted along

Barnes' line. The Confederate attack, the brigade of G. T. Anderson,

struck Tilton's line and the Third Corps troops on his left. Colonel Ira

C. Abbott, commanding the 1st Michigan, stated that he had his men lying

down while the rest of the line began to respond to Confederate fire.

When the Confederates were within forty rods Abbott ordered his men to

their feet and to fire by file "which made a dreadful confusion" in the

enemy ranks. Sweitzer ordered his other two regiments, the 62nd

Pennsylvania and the 4th Michigan, to change front to the left and form

lines behind the 32nd Massachusetts. There were now no Fifth Corps

troops facing west towards the Peach Orchard except for the right flank

of the 118th Pennsylvania. [61]

The Confederate attack (the brigades of G. T.

Anderson and Joseph B. Kershaw) was renewed against the Stony Hill and

commenced against the Peach Orchard. Three Confederate regiments started

to turn towards Barnes' right flank and towards the Union batteries

stationed along the Wheatfield Road. Colonel Tilton, anxious about his

right flank, reconnoitered personally and decided that the enemy was

trying to outflank him. The historian of the 118th Pennsylvania reported

that the batteries along the Wheatfield Road, except for two sections of

Bigelow's Battery, had retired. The enemy was "about to envelop the

entire exposed and unprotected right flank of the regiment." Tilton was

ordered to retire and take up a new position, in two lines "at the left

and rear of a battery (Bigelow) which had been posted about 300 yards to

my right and rear." This brought Tilton's Brigade into Trostle's Woods,

along the north side of the Wheatfield Road, facing towards the west.

The 118th Pennsylvania was on the right of the first line. Although it

is not clear, it is possible that the 1st Michigan was on the left of

the first line and the 18th and 22nd Massachusetts were on the right and

left of the second line. [62]

Sweitzer reported that there was no enemy on his

front except in front of the 32nd Massachusetts. Barnes had sent

Sweitzer precautionary orders "that when we retired we should fall back

under cover of the woods." When Colonel Prescott, 32nd Massachusetts,

was told this he responded, "I don't want to retire; I am not ready to

retire; I can hold this place..." When told this was only a

precautionary order, Prescott apparently calmed down, and was satisfied

that it was not a preemptory order. Shorty thereafter, however, Tilton

retired and Sweitzer received orders to do the same. Sweitzer's new

position placed him along the Wheatfield Road, to the left of Tilton in

Trostle's Woods. The two brigades thus formed a right angle to each

other, Tilton facing west and Sweitzer facing south. [63]

Trostle's Woods formed a rough triangle. It was about

200 yards south to north and about 500 yards east to west along the

Wheatfield Road. The Trostle Farm was about 150 yards further north from

the northwest corner of the woods. Tilton's Brigade, occupied a frontage

of about 100 yards. This left a gap, of about 250 yards, from Tilton's

right flank to the Trostle Farm. Sweitzer occupied a frontage of about

280 yards.

There are some unexplained actions, and perhaps some

lapses in judgement, by the Fifth Corps commanders on the Stony Hill.

Sweitzer does not explain why, when the right flank was threatened, he

did not order the 62nd Pennsylvania and the 4th Michigan to change front

to face west, as they were originally posted. Tilton did not explain why

the 18th Massachuestts was not moved to the right of the 118th

Pennsylvania to strengthen that flank. While the batteries along the

Wheatfield Road were vulnerable without direct infantry support, along

with Sweitzer and Tilton, they may have been able to catch the

Confederate infantry in a cross-fire, and been better able to stop the

attack. Also unexplained is why Barnes, when he ordered a withdrawal,

did not inform the Third Corps troops to his left. This withdrawal left

the Third Corps right exposed and forced them to retire as well.

Approaching the field, as Barnes and the Third Corps

troops were falling back, was Brigadier General John C. Caldwell's First

Division, Second Corps (3320 men). Caldwell had received orders from his

corps commander, Major General W. S. Hancock, to report to Sykes.

Caldwell sent an aide, Lieutenant Daniel K. Cross, to find Sykes "but he

did not succeed in finding him." While Caldwell did state he met a staff

officer, who he thought was Lieutenant Colonel Locke, Sykes" assistant

adjutant-general, at least one historian believes that it could just

have easily been Major Henry E. Tremain, of Sickles' staff. It is known

that Major Tremain did lead Caldwell's Third Brigade into position.

Caldwell's Division cleared the Wheatfield and established a line about

600 feet south and west of the position held by Barnes. [64]

|

|

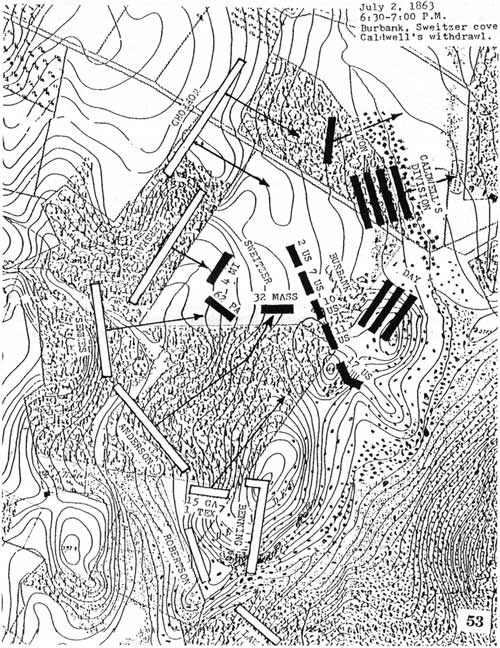

"The Second Day at Gettysburg: Day of

Decision," 1992 Association of Licensed Battlefield Guide Battlefield

Seminar. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

It is not clear whether or not Sykes knew that

Caldwell was supposed to report to him for orders. With elements from

three different corps (Second, Third and Fifth) now fighting along

Sykes' front, Menade had not placed anyone in overall command. Sykes, in

corps command only since June 28, may have been hesitant to give orders

to any but his own troops without clear authority from Meade. This was a

point Sykes would have been sensitive about considering the actions of

Third Corps staff officers trying to issue orders to Fifth Corps troops

without authority. Sykes was probably in the process of bringing up the

rest of his Corps when Caldwell arrived on the field.

As Caldwell was advancing through the Wheatfield,

Romeyn B. Ayres was advancing his two brigades of Regulars from the

north slope of Little Round Top across Plum Run to Houck's Ridge and a

stone fence on the east edge of the Wheatfield. Lieutenant James P.

Pratt described the advance "over rocks and in the marsh. A dozen paces

forward, and we came within this enfilading fire. Men began to fall very

fast, but the line kept steadily on. We gained the other side, and lay

down." Colonel Sidney Burbank led the Second Brigade (958 strong)

followed by Colonel Hannibal Day's First Brigade (1574 strong). The

enfilade fire described by Pratt was coming from Confederate soldiers

in Devil's Den and on the south end of Houck's Ridge. Once on Sidney

Burbank the ridge, the 17th U. S.. Infantry, Burbank's left flank

regiment, had to refuse part of its line to try to cover this fire.

Because Caldwell was in his front, and probably because Sweitzer was

marching across the Wheatfield, Ayres could not advance. [65]

Caldwell, meanwhile, was looking for some aid for his

hard-pressed division. He asked Sweitzer if he could advance across the

Wheatfield in support. Sweitzer referred Caldwell to Barnes, who was

close by. Barnes then asked Sweitzer if he would take his brigade in. "I

would", Sweitzer said, "if he wished me to do so." Barnes said he did,

and then gave "a few patriotic remarks", probably to the 32nd

Massachusetts, to which the command responded with a cheer before

advancing. Sweitzer advanced to the stone fence on the south side of the

Wheatfield to support the troops he supposed were in his front. The 4th

Michigan extended beyond the wall to near the position held by the 32nd

Massachusetts earlier in the afternoon. Ayres, after consulting with

Caldwell, also prepared to move through the Wheatfield and "occupy the

woods in my front." Sykes, at about the same time, sent Lieutenant

Ingham with similar orders for Ayres but Ingham did not reach Ayres in

time. Events in the Wheatfield were starting to happen too fast. [66]

The Union positions at the Peach Orchard had

collapsed and Third Corps troops began streaming towards the rear.

Confederate troops, under Brigadier General W. T. Wofford, began

advancing down the Wheatfield Road. This became part of a general

Confederate advance south of the Wheatfield Road with portions of four

Confederate brigades (Wofford, Kershaw, Semmes, Anderson) converging on

the Wheatfield itself. Three Fifth Corps brigades were about to be

caught in the middle of this advance.

Tilton, in Trostle's Woods, reported "squads of men

belonging to the 2d & 3d Corps breaking through the ranks in their

hurry to the rear..." Some skirmishers from the 118th Pennsylvania were

trying to assist in keeping Confederate skirmishers from Bigelow's

Battery. Watson's Battery was temporarily stationed near the Trostle

Farm before moving to a position about 800 feet east of the farm.

Tilton, whose horse had been shot, was unable to maintain his position

and retired from Trostle's Woods. Tilton assumed a new position just

north of Little Round Top and reported to Sykes. [67]

Barnes may have been wounded while trying to direct

Tilton in Trostle's Woods. The historian of the 118th Pennsylvania

remembered that Barnes rode "valiantly amid the thickest of the fray,

encouraging, persuading, directing, with that same courageous judgement

which had ever been his distinguishing characteristic." Sweitzer

reported that after he had retreated from the Wheatfield, and shortly

after dark, he was placed in command of the division as Barnes was

reported missing. He also stated that Barnes "returned about midnight or

afterwards and assumed command of the Divn." [68]

At the stone wall in the Wheatfield, Sweitzer's

color-bearer suddenly remarked: "Colonel, I'll be _____if I don't think

we are faced the wrong way; the rebs are up there in the woods behind

us, on the right." This was soon confirmed by reports from the 62nd

Pennsylvania and the 4th Michigan. These units were ordered to change

front to met this new threat. Sweitzer sent an aide to communicate with

Barnes but he was no longer in Trostle's Woods, as the enemy had reached

his position and "as far back as where we had started from, and along

the road in rear of the wheat-field." Most of Sweitzer's brigade, now

finding themselves in hand-to-hand combat, started to pull out. Colonel

Harrison Jeffords, 4th Michigan, was killed trying to rescue his

regimental colors. [69]

Once Sweitzer had cleared his front, Ayres also tried

to move into the Wheatfield, Burbank's brigade, using the crotchet made

by the left flank of the 17th U. S., tried to do a left wheel to connect

with Sweitzer's left flank. Burbank, after completing a half-wheel,

reported that at first he received no fire on his front, but suddenly

was receiving a heavy fire on his right flank. Burbank was forced to

withdraw from the field under this heavy fire. When Burbank reached the

stone wall on Houck's Ridge, after Day's Brigade had started to fall

back, the brigade realigned itself before continuing the withdrawal to

Little Round Top. [70]

This Confederate attack seems to have taken place

while both Sweitzer and Burbank were in the Wheatfield. With all the

smoke and confusion it is possible that neither Sweitzer nor Burbank

realized exactly where the other was in the Wheatfield. It also appears,

from the flow of events, that Burbank may have had a chance to withdraw

before Sweitzer. Burbank and Day retreated directly to Little Round Top,

Sweitzer headed toward Tilton's position, and Confederate troops started

moving into Plum Run.

Captain Frank C. Gibbs, Battery L, 1st Ohio Light,

responding to orders from Sykes, placed two guns on the right (north)

slope of Little Round Top and four guns north of the Wheatfield Road. To

Gibbs' right was Captain Almont Barnes, Battery C, 1st New York, who was

not in a very good position to use his guns. Burbank and Day withdrew

through Gibbs' guns on the slope. As soon as the front was cleared, "the

enemy put in his appearance, and we received him with double charges of

canister, which were used so effectively as to compel him to retire."

[71]

While Gibbs' Battery was in action, Captain August P.

Martin was notified that General Weed had been mortally wounded. Weed

had asked to see Charles Hazlett. Weed gave him instructions for the

payment of some small debts and, as Hazlett drew closer to receive a

confidential message, he was shot in the head. [72]

Company K, 1st Pennsylvania Reserves

Also helping to compel the Confederates to retire was

Crawford's Third Division, the Pennsylvania Reserves. The ever present

Captain Moore, of Sickles' staff, stated that he met Crawford at Power's

Hill. Crawford, who, for some unexplained reason, thought Moore was on

Meade's staff, moved toward the Round Tops under Moore's direction.

Crawford stated that he "followed through the woods in my front to a

road which, starting at the Baltimore turnpike, runs in a Southerly

direction, crossing the Taneytown Road and skirtng the foot of the

Northern slope of Round Top, becomes a cross road from the Taneytown to

the Emmittesburg road." [73]

Arriving near Little Round Top, Sykes ordered

Crawford to mass his command to the right (north) side of the Wheatfield

Road. Crawford was no sooner in position than he received a new order to

cross the road to the north slope of Little Round Top. At the same time,

he was ordered to detach one brigade to aid Vincent on the south slope.

This was just before Ayres withdrawal from the Wheatfield, The Third

Brigade, under Colonel Joseph W. Fisher, minus the 11th Reserve, was

sent to Vincent's aid. Fisher's Brigade took position behind the 20th

Maine and the 83rd Pennsylvania, just prior to Chamberlain's advance.

The 11th Reserve became temporarily attached to the First Brigade, under

Colonel William McCandless. Crawford formed McCandless into two lines,

the 6th, 11th, and 1st, in front and the 13th and 12th Reserves in the

rear. Coming up behind Crawford, and passing to his left flank was the

98th Pennsylvania from the Third Brigade, Third Division of the Sixth

Corps. [74]

The 98th Pennsylvania charged past Crawford's line

and into Plum Run. Who ordered Crawford forward is open to

interpretation. Sykes, in his official report, said he ordered the

charge. Crawford maintained that when he asked Sykes for orders, he was

authorized "as I was upon the ground, to act as I deemed proper."

[75]

Whoever issued the orders, the Reserves now fired two

well-directed volleys, gave a cheer and charged forward at a run. George

Swope, 1st Reserves, remembered this as "a moment of great excitment -

Every member of the Reserves (were) anxious to advance - General

Crawford amid tremendous cheers seized our Regimental flag and ordered

the charge. I saw him wave the colors and advance with them down Little

Round Top, probably half the distance to Plum Run." The Confederates

were forced out of Plum Run Valley and driven back to the stone wall,

previously occupied by Ayres, "for the possession of which there was a

short but determined struggle." The Confederates were driven from the

wall and across the Wheatfield to Rose's Woods. [76]

Watson's and Walcott's Batteries were caught between

the advancing Confederates and the Union line. Watson's Battery was

overrun east of the Trostle Farm, but Lieutenant Samuel Peeples "having

procured the services of the Garabaldi Guards..." (39th New York of the

Second Corps) led a counterattack, recaptured the guns and took

everything safely to the rear. Walcott, on the north side of the

Wheatfield Road, along the lane leading to the Jacob Weikert Farm, had

no infantry support nearby. When Walcott saw the Confederates emerge

from Trostle's Woods he ordered his guns spiked and one was before they

were abandoned. Three regiments from the Sixth Corps, the 62nd New York,

and the 93rd and 139th Pennsylvania, delivered two volleys into the

Confederate ranks before advancing, recapturing Walcott's guns and

taking position along the Weikert lane. [77]

After the fighting, and as darkness was setting in,

Colonel James C. Rice, commanding Vincent's brigade, ordered the 20th

Maine to advance and occupy Big Round Top. Fisher also detached two

regiments, the 5th and 12th Reserves, from his brigade to aid in this

occupation. By the day's end, the Fifth Corps occupied both Big and

Little Round Tops in force, with McCandless Brigade occupying an

advanced position near the Wheatfield, Sykes was able to state that "the

key of the battlefield was in our possession intact. Vincent, Weed, and

Hazlett, chiefs lamented throughout the Corps and army, sealed with

their lives the spot intrusted to their keeping, and on which so much

depended." [78]

At 3:00 a.m., July 3, Walcott's and Almont Barnes'

Batteries were assigned to the Second Division, Sixth Corps and helped

to guard the extreme left flank of the army. Although the batteries did

not fire a shot on July 3, they did come under enemy fire. At 1:45 p.m.,

Sykes received a report from Colonel Kenner Garrard, commanding Weed's

Brigade, and Tilton that Confederates were advancing on their left and

front. Sykes was subsequently told by headquarters that if he was

attacked, it was not Meade's "purpose to withdraw any portion of your

troops from the positions they now occupy." At no time on July 3 did

Sykes receive orders to advance his whole corps. [79]

Crawford received orders at 5:00 p.m. "to advance

that portion of my command which was holding the ground retaken on the

left, and which still held the line of the stone wall in front, to enter

the woods, and, if possible, drive out the enemy. It was supposed that

the enemy had evacuated the position." Crawford ordered McCandless, with

the 11th Reserves, to advance. He also requested support from Brigadier

General Joseph J. Bartlett, commanding both the Third Brigade, Third

Division and Second Brigade, First Division, Sixth Corps, who sent

Colonel David J. Nevin (Third Brigade, Third Division) to Crawford's

support. Nevin's main line advanced about 200 yards behind McCandless as

he crossed the Wheatfield. The 6th Pennsylvania and 139th Pennsylvania

(Nevin) sent skirmishers to the right to clear out Confederate

skirmishers. The 139th Pennsylvania also claimed to have recaptured one

brass Napoleon and three caissons belonging to Bigelow's Battery. [80]

McCandless discovered a line of the enemy in the

woods to his left and at a right angle to his line. This was Brigadier

General Henry L. Benning's Brigade from Hood's Division, Longstreet's

Corps, which had been left in the woods by a misunderstanding of orders.

By the time the orders were resolved Colonel D, M. Dubois, 15th Georgia,

found himself almost trapped between McCandless and Nevin and had to

fight his way out. The rest of the brigade managed to get out with

slight loss. This armed reconnaissance found the enemy to be in force

and still willing to fight. [81]

On July 3, Brigadier General Charles Griffin, the

regular commander of the First Division, arrived on the field. For some

reason not fully explained, Griffin did not relieve the wounded Barnes

until July 4. One source has Griffin stating: "To you General Barnes,

belongs the honor of the field; you began the battle with the division,

and shall fight it to the end." Whether this was Griffin's real reason

is not known. It is also speculated that Griffin had talked with Sykes

about the division's performance on July 2 and that Griffin did not want

to assume any responsibility for the division's actions on the field.

Sweitzer reported that after he had retreated from the Wheatfield, and

shortly after dark, he was placed in command of the division as Barnes

was reported missing. He also stated that Barnes "returned about

midnight or afterwards and assumed command of the Divn." [82]

At 7:00 a.m. on July 4, Day's Brigade was ordered out

on a reconnaissance. After crossing Plum Run the skirmishers were

ordered to advance and drive in the enemy pickets. The 3rd, 4th, and 6th

U. S. formed the first line supported by the 12th and 14th U. S. Major

Grotius Giddings, 14th U. S., received orders to move his regiment

through a small piece of woods on the left to see who occupied the house

(probably the Rose Farm): Captain Guido Ilyes, commanding the

skirmishers, reported that the house contained wounded from both sides

plus "a large quantity of arms." At the same time, two Confederate

cannons opened fire with shell at an easy range. Giddings received

orders to fall back and rejoin the brigade and then the brigade moved

back to the east side of Little Round Top to the rear of Hazlett's

Battery. [83]

The was some confusion associated with the Fifth

Corps on July 5. If Sykes had no troops with Sedgwick's Sixth Corps or

in Sedgwick's support, he was authorized to "move out on the road to

Emmitsburg, the left-hand road, going a short distance on the Taneytown

road, and leaving it before it crosses Rock Creek." After moving out

four or five miles, Sykes was to wait for further orders from Major

General O. O. Howard, commanding Eleventh Corps. At 4:30 a.m. Sykes

reported that his men were in hand and as soon as his pickets were

recalled he would move. At 10:20 a.m. headquarters wanted an explanation

of a report that Sykes was in readiness to move with the Sixth Corps; no

orders for such a movement having been issued. This confusion was

apparently not straightened out until much later when at 7:30 p.m. Meade

informed Sedgwick that he had not remembered directing Sykes to support

Sedgwick but instead had authorized his moving with the Eleventh Corps.

Sykes reported at 9:30 p.m. that he was encamped on the south side of

Marsh Creek along the Emmitsburg Road and would march at 4:00 a.m. "in

order to pass through Emmitsburg before any of the troops behind me can

reach the rear of my column." [84]

On July 6, Crawford requested, through Meade, that

his Second Brigade, left at Alexandria, be ordered to re-join the

division. "Its separation," Crawford noted, "was merely temporary..."

The brigade never rejoined Crawford. [85]

By July 10, the Fifth Corps had marched 55 miles and

had reached the Antietam at Delaware Mills. The Corps had marched

through Emmitsburg, Creagerstown, Utica, and Middletown, crossing the

Catoctin and South Mountain ranges at High Knob and Fox's Gap. Sykes

reported that the Antietam was "very high and swift." A scout from the

Cavalry Corps reported no Confederates at Sharpsburg and that they had

"ceased crossing at Williamsport." [86]

Between July 10 and 14, Sykes maneuvered in the face

of the enemy. His men also set to work constructing breastworks and

rifle-pits. On July 13, Sykes was directed to place the Fifth Corps to

the right of Hays (Second Corps) and the left of Sedgwick in the area of

Williamsport. Sykes felt the interval was not large enough for two

divisions. Crawford was placed on the right of Hays and one brigade from

Griffin's Division was placed to the right and rear of Crawford. On July

14, the Corps pursued the Confederates two miles beyond Williamsport. On

that date, the Gettysburg Campaign came to an end. It was now time to

asses the costs of the campaign. [87]

According to the June 30 muster report, the Fifth

Corps numbered 10,907 officers and men. By the end of the campaign, the

Corps had sustained 2,187 casualties, about 20% of its total strength.

But the casualties were not evenly distributed among the various units.

Crawford's Division had 210 casualties out of 2862 engaged. Barnes lost

904 out of 3417 and Ayres lost 1029 out of 4021. Burbank's brigade of

Ayres division had some of the highest casualties in the Corps. The 17th

U. S., for example, lost 58% of its men (150 out of 260 engaged).

Sweitzer's Brigade officially lost about 30% of its strength (427 out of

1423) but one regiment, the 9th Massachusetts, was only lightly engaged

in skirmish duty near Wolf's Hill, while the other regiments were caught

in the maelstrom of the Wheatfield. The Artillery Brigade, as a whole,

had few casualties, although Watson's Battery had the highest percentage

loss of any Union battery during the battle (22 lost out of 71 engaged).

[88]

Colonel Patrick R. Gurney, 9th Massachusetts, stated

that when he rejoined Sweitzer's Brigade, it seemed "more appropriate to

say that we constituted the Brigade...The Brigade -except ourselves, had

been fought nearly to extinction." The 4th Michigan lost 165 out of 342

and the 62nd Pennsylvania lost 175 out of 426 engaged. The 9th

Massachusetts was, therefore, ordered to join Tilton's Brigade. [89]

Captain James A. Bates, Chief Ambulance Officer,

reported that he was "kept constantly running from the hospital to the

battle-field until 4 a.m. July 3." The 81 ambulances had transported

1300 wounded. At 10:00 a.m. July 3, J. J. Milhau, the Fifth Corps

Medical Director, ordered the wounded to be moved one mile to the rear

"as the enemy had commenced to shell the hospital." This time the 81

ambulances moved 2600 wounded one and a half miles. [90]

Sykes, in his after-action report, stated that the

Corps buried 404 Confederate dead, captured 13,351 small arms, and one

Napoleon. Sykes was happy to report that "the Fifth Corps sustained its

reputation. An important duty was confided to it, which was gallantly

performed....Prompt response and obedience to all orders characterized

them." [91]

How did Sykes, himself, perform during the campaign

and battle?

- Sykes assumed command of the Corps on June 28, the day Meade assumed

command of the Army of the Potomac.

- On the march from Frederick to Gettysburg, Sykes kept the First and

Second Divisions moving together and left aides and guides for the Third

Division with instructions to close-up as soon as possible.

- By noon of July 2, the Corps was united on the battlefield. On

receipt of Meade's orders, Sykes moved the Corps to the left in a timely

manner. (Even Birney admitted this.) When called on, by Warren, for a

brigade, Vincent was sent immediately to Little Round Top. Sweitzer and

Tilton were posted on the Stony Hill to help support the Third Corps in

Rose's Woods.

- Sykes appears not to have given Barnes any specific orders after

posting him, but, instead, allowed Barnes to use his own discretion in

the handling of the First Division.

- Sykes, also, presumably, saw to the posting of his Second and Third

Divisions.

- When he saw Weed moving to join Sickles, he promptly ordered it back

to Little Round Top.

- It is not clear that Sykes was aware that he had authority over

Caldwell's Division. Sykes, as a career officer, was probably reluctant

to issue orders to troops not under his immediate command, without clear

authorization. When he realized that Caldwell's left was in danger, he

did order in the best troops he had, the two brigades of Regulars. Sykes

allowed, or ordered, Crawford to advance while he helped to rally the

First and Second Divisions.

Sykes, who may have partially still been in the

mind-set of a division commander, seems to have done as good a job as

could have been expected. He did carry out his assignment from Meade to

hold the left and by the end of the day the key to the battlefield was

firmly in the grasp of the Fifth Corps.

The Fifth Corps would continue to serve as a unit

with the Army of the Potomac, but as with most of the units, the

Gettysburg Campaign would bring changes to the Corps organization.

On August 14, the two brigades of Regulars, much

reduced in numbers, were ordered to Alexandria, and thence to New York

City to help quell the draft riots. Although some of these units would

return to the Army of the Potomac, they did so as a mere shadow of their

former selves. [92]

James Barnes went on sick leave after his wounding on

July 2. He served on court-martial duty and commanded the defenses of

Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia. He ended the war in command of the

prison camp at Point Lookout, Maryland. He was brevetted a major general

of volunteers on March 13, 1865, for meritorious services and mustered

out of volunteer service on January 15, 1866. He died on February 12,

1869 in Springfield, Massachusetts. [93]

Charles Griffin resumed command of the First Division

on July 4 and led it through the rest of the war. On April 1, 1865, he

assumed command of the Corps and served as one of the officers assigned

to carry out the terms of Lee's surrender. During the battle of the

Wilderness, Lieutenant General U. S. Grant heard Griffin utter some

remarks that Grant took to be mutinous. When Grant told Meade that

Griffin ought to be arrested, Meade merely replied "...its only his way

of talking." Griffin was brevetted major general, U. S. Army, on March

13, 1865, for gallant and meritorious services in the field. In 1866 he

served on a board to determine the kind of small arms to be used by the

Army and on July 28, 1869, was appointed colonel of the 35th Infantry.

While in temporary command of the Fifth Military District (Texas and

Louisiana), Griffin refused to leave his post when yellow fever broke

out. He died at Galveston, Texas, on September 15, 1869, at the age of

41. [94]

Romeyn B. Ayres remained with the Fifth Corps to the

end of the war. He received the brevets of major, lieutenant colonel,

and colonel in the regular army for gallant and meritorious services at

Gettysburg, the Wilderness and Weldon Railroad. He was brevetted a major

general, U. S. Army, on March 13, 1865, for gallant and meritorious

services in the field during the Rebellion. Upon the reorganization of

the army in 1866, he was appointed lieutenant colonel of the 28th

Infantry. On July 15, 1879, he was promoted to colonel of the 2nd

Artillery. He died at Fort Hamilton, New York, on December 4, 1888,

still on active duty after 41 years of service. [95]

Samuel Wylie Crawford also continued with the Fifth

Corps in command of the Third Division until the end of the war. He

received the Regular Army brevets of colonel, brigadier general and

major general for the battles of Gettysburg and Five Forks, Virginia,

and for gallant and meritorious services in the field. He was named

colonel of the 16th Infantry on February 22, 1869, but was transferred

to the 2nd Infantry on March 15. He retired from the service on February

19, 1873, and in 1875 was placed on the retired list with the rank of

brigadier general. He purchased the land in Plum Run valley, the scene