|

Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park California |

|

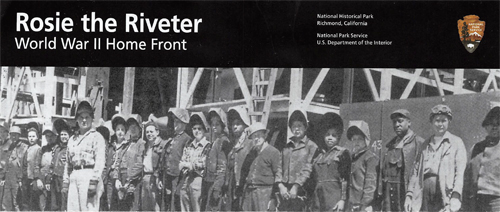

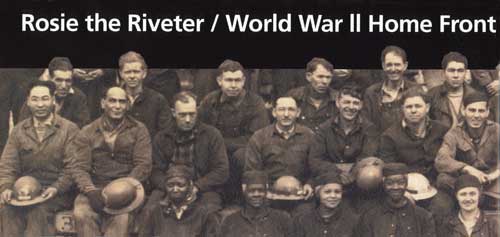

NPS photo | |

December, 1941: A sudden attack on a distant US naval base transformed America overnight into the "home front." Everything changed, especially the swelling industrial workforce. It included millions more minorities, in particular African Americans, and women, embodied by "Rosie the Riveter." Richmond, California typified wartime boomtowns across the country that endured deep and rapid change as migrants sought work in defense industries.

Arsenal of Democracy

WARTIME AMERICA In his December 1940 radio address, delivered as German divisions rolled across Europe, President Franklin D. Roosevelt promised to make America "the great arsenal of democracy." Even before the nation entered the war a year later, a new partnership of government, industry, and labor focused the country's energies and vast productive capacity on that goal, turning out enormous stocks of weapons for its own armed forces and its allies.

This massive effort and the demands of "total war" altered the lives of Americans, often permanently. Living standards rose as rapid industrial employment helped end the Depression. Regulations like wage and price controls played a bigger role in people's lives. War brought out the worst and best in us: black market activity coexisted with shared sacrifice. Japanese Americans were interned and some cities endured race riots even as wartime needs spurred innovative social programs.

THE HOME FRONT LEGACY By war's end the United States was a world power. The worker migrations permanently changed the nation's demographic patterns. We were more prosperous, more urban, less regional. Wartime social institutions like employee health plans, day care, and workplace safety standards became permanent. New technologies—antibiotics, jet propulsion, computers, nuclear power—had been accelerated. Millions of men and women of color had taken the first toward an equal place in society.

This time is vividly recalled by Richmond's historic shipyard-related structures. They are the core of the national park area established to tell the story of the World War II home front.

MOBILIZING PEOPLE

The government mounted an extensive poster campaign to promote the war effort among civilians, extolling hard work, conservation, war bonds, and rationing. "B-stickers" displayed by defense workers allowed them more gasoline than the general public.MOBILIZING AMERICA

At the peak of its wartime industrial capacity, the United States accounted for 40 percent of all weapons and equipment produced worldwide. At "Prairie Shipyards", landing ships destined for amphibious operations were launched on rivers.The West Coast was a center of wartime shipbuilding. The San Francisco Bay area alone, including the Richmond yards, launched 45 percent of cargo tonnage and 20 percent of warship tonnage during the war. This output hinged on preassembled parts, made in 128 cities and towns in 33 states, rolling nonstop into Richmond shipyards.

MOBILIZING INDUSTRY

Ford Motor Co. built the Willow Run plant in Michigan to produce B-24 bombers. The Army-Navy Excellence Award "E" pin was given to outstanding workers.

Seeking Equality at Home

As the defense industry geared up before the United States entered the war, African Americans and other minorities found newly created jobs barred to them. In the face of the country's denial of civil rights to its minorities, America's condemnation of Nazi oppression looked increasingly hypocritical. Facing a planned March on Washington in 1941 to protest discrimination. President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802 requiring fair hiring practices in the defense industry.

More blacks, Asians, and Hispanics worked during the war, but were often placed in unskilled jobs, and many suffered workplace and housing discrimination. Still, wartime work represented new opportunities, and while many lost their jobs at war's end, their expectations had been raised. Minorities were more motivated to press for their rights in the coming decades.

THE DOUBLE-V

As African Americans continued to suffer discrimination due to weak enforcement of Executive Order 8802, they created the "Double-V Campaign," for victory over fascism abroad and racism at home.

Mass Production Miracles

How did America answer Roosevelt's call to become the "arsenal of democracy"? Part of the answer was the sheer number of workers, working in shifts around the clock. But prefabrication and assembly-line techniques, especially at Richmond's Kaiser yards, made the difference, allowing workers to launch a huge armada of transport vessels and warships.

Large sections of ships were assembled in a Prefabrication Yard that served Richmond's shipyards. Deckhouses, for instance, were built on roller runways in the Prefab Plant. As the basic deckhouse sections moved along the rollers, workers joined heavy structural components and installed plumbing and wiring.

The finished deckhouse was transported by special tractor trailer to a building slip, where cranes lifted it onto the rising hull. This significantly reduced the time needed to build a ship, as did the use of welding. Ships had traditionally been riveted together, but builders adopted welding techniques developed just before the war, saving time, steel, and ultimately lives.

THE WARTIME WORKPLACE

Workshirts, training manuals, war bond drives—all part of the workplace for defense workers during the war. The time's attitudes toward women were often reflected in such materials.REMEMBERING AN ERA

Many defense workers carried lifelong memories of their experience, saving ID cards and badges, pay slips, and photos of their younger days.

Help From the Home Front

With the Allies suffering early defeats on the battlefield, Americans quickly understood the magnitude of the situation and were willing to share the sacrifices made by those who fought. "There's a war to be won!" was the common response to those who shirked. People saved fats for use in explosives, held salvaging and recycling drives, bought war bonds, planted victory gardens, and canned foods. They volunteered for the Civil Defense Corps and endured gas and tire rationing, shortages, and blackouts.

Popular songs caught the temper of the times, from "jump" songs like Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy; to I'll Walk Alone and I'll Be Seeing You, evoking the sadness of separation; to When the Lights Go On Again, expressing everyone's wistful yearning for the war's end.

SCRAP DRIVES

Recycling materials for military use was a vital civilian activity. Children could contribute to the war effort by gathering scrap metal, rubber, and fiber.

Women in the Workforce

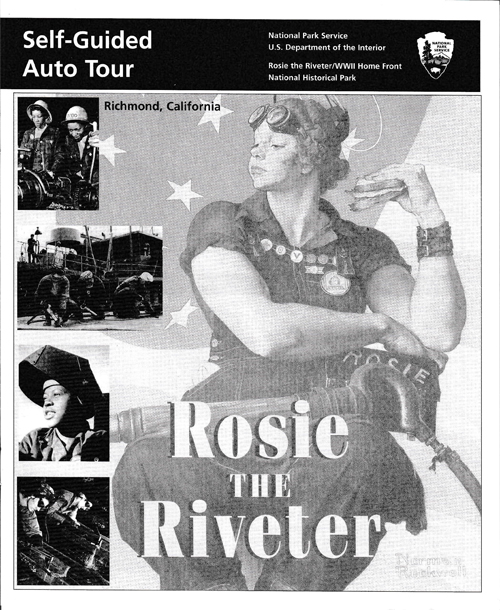

ROSIE THE RIVETER and WENDY THE WELDER

Some six million women entered the US workforce during the war. While many needed no urging to aid the war effort, the government actively recruited them, first targeting single white women. The appeal later extended to married women, then minority women. Many people, including women, had to overcome Depression-era attitudes about women taking jobs from men—and about married women working at all. Though women across the social spectrum worked during the war, minorities and working-class women (many of whom had always worked) made up half of those who entered the defense workforce.

As they performed tasks that had always been done by men, women met with condescension, unequal pay, and harassment. Gradually they were accepted, especially as they proved themselves at least as skilled as men at a number of tasks. Defense jobs were often non-industrial—many were clerical, and Women Airforce Service Pilots ferried planes and towed training targets. Women worked in non-defense jobs formerly reserved for men: bus drivers, journalists, lab technicians, agricultural workers in the Women's Land Army. By 1944 women made up almost a third of the workforce. After the war they were urged to give up their jobs to returning veterans. Though many lost what they had gained, women had clearly proven they could do "men's work."

"ROSIE THE RIVETER"

Many female defense workers were riveters, and the "Rosie the Riveter" icon and song were a central part of the campaign to recruit women and persuade men to accept them.

Wartime Richmond

WORKING IN RICHMOND

BUILDING SHIPS FOR WAR How did Richmond become a wartime shipbuilding center? Its rail and deepwater connections made it a natural site for Henry Kaiser's shipyards and over 50 other war-related industries. The shipyards were born of the 1940 Emergency Shipbuilding Program, which called for a new shipyard in Richmond to build 30 cargo ships to help replace those Britain had lost to German U-boats. Within two years Kaiser, new to shipbuilding but experienced in large industrial enterprises, had built a complex of four yards.

During the war the government commissioned over 3,200 Liberty and Victory ships for the expanded US cargo fleet and the Lend-Lease program. These types accounted for most of the 747 ships launched in Richmond, more than any other yard in the country. Kaiser's success was due in great part to innovative prefabricated assembly methods. These methods also allowed inexperienced workers to do small, repetitive tasks, like simple welding, which sped construction and opened up more jobs for new workers, especially women.

Veterans in the skilled shipbuilding trades resisted this "deskilling" of tasks and the hiring of inexperienced workers, but the Kaiser yards were among the earliest to employ women; by 1944 they made up 41 percent of welders. As outsiders of different backgrounds arrived, racism and cultural differences caused problems at the yards. Despite the tensions 10,000 African Americans eventually worked here, along with smaller numbers of Hispanics, Asian Americans, and American Indians.

LIVING IN RICHMOND

MAKING A NEW LIFE The wartime migrations of workers to industrial centers affected many cities, but Richmond was particularly hard hit. At its peak 90,000 people worked in the shipyards, quadrupling its size. The exploding population overwhelmed the city's transportation, housing, education, and public health and safety services, though Richmond and the shipyards alleviated some of the problems. Kaiser's Permanente Health Plan offered health care to workers, with onsite first aid stations and a local field hospital.

A Richmond-Federal-Kaiser partnership provided workers with housing and child-care centers. But housing remained in short supply, forcing workers to come up with their own solutions: railroad cars, cobbled-together shacks, trailers. Some took turns sleeping in "hot beds" used around the clock. African Americans and other minorities lived in even poorer quality segregated housing. Long public transportation rides, food shortages, and racial issues persisted, but Richmond and its diverse population coped. They made it work.

RICHMOND: The Wartime Waterfront

THE SHIPYARDS IN 1944 Some of the wartime structures, including the Shipyard No. 2 basin and the Shipyard No. 3 building docks, remain intact—one reason Richmond was chosen as the National Park System's site to tell the home front story.

Richmond Today

VISITING THE PARK A good place to start is the Visitor Education Center, where you can view exhibits and a short film. It is open from 10 am to 5 pm year-round except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. The Rosie the Riveter Memorial in Marina Bay Park is open year-round, dawn to dusk, as are other city parks within the National Park boundary.

Visit historic buildings like the Ford Assembly Building, converted in wartime to a tank depot where military vehicles were equipped before shipment.

You can take a tour of the city's historic World War II sites and structures, take a self-guided auto tour, or walk the Bay Trail with its historic markers. See the park website for maps, directions, tour schedules, and information on events and programs.

ACCESSIBILITY The visitor center and Rosie the Riveter Memorial are fully accessible, as are other city parks within the park boundary. Service animals are welcome.

REGULATIONS Follow state laws regarding firearms.

SS OAK VICTORY

Be sure to visit this Victory Ship, moored at Shipyard No. 3. Built in Richmond

in 1944. the ship carried supplies and troops to the Pacific theater of war.

Visit www.ssredoakvictory.com for directions, hours, fees, and

accessibility.

ROSIE THE RIVETER MEMORIAL

The Memorial, on the site of a Shipyard No. 2 building slip, evokes the yard's

celebrated shipbuilding techniques. The main sculpture of a hull under

construction and the Keel Walk to water's edge include images and memories of

the women who worked here.

Source: NPS Brochure (2011)

|

Establishment Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park — October 24, 2000 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Brochures ◆ Site Bulletins ◆ Trading Cards

Documents

A Socioeconomic Atlas for Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park and its Region (Jean E. McKendry, Cynthia A. Brewer, Jonathan P. Harahush and Joel M. Staub, 2004)

Feasibility Study Report for Designation of Rosie the Riveter Memorial as a National Park System Area Final (June 2000)

Fighting the Good Fight: The Utah Home Front during World War II (Jessie L. Embry, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 63 No. 3, Summer 1995, ©Utah Historical Society)

Foundation Document, Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park, California (February 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park, California (January 2017)

General Management Plan / Environmental Assessment, Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park (August 2008)

General Management Plan Summary, Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park (September 2010)

Kansas At War: The Home Front, 1941-1945 (Patrick G. O'Brien, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 17 No. 1, Spring 1994)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park (March 2010)

Museum Management Plan East Bay Parks (John Muir NHS, Eugene O'Neill NHS, Port of Chicago Naval Magazine NMem and Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front NHP) (David Blackburn, Kent Bush, Dave Casebolt, Carola DeRooy, Lucy Lawliss, Diane Nicholson and Paul Rogers, May 2007)

Newsletter (Partnering for the Home Front): Spring 2008 • Summer 2008 • Winter-Spring 2008-2009 • Summer-Fall 2009

Oral History Project (Bancroft Library)

The Newelletters: E. Gail Carpenter Describes Life on the Home Front, Part I (Charles William Sloan, Jr., ed., extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 11 No. 1, Spring 1989)

The Newelletters: E. Gail Carpenter Describes Life on the Home Front, Part II (Charles William Sloan, Jr., ed., extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 11 No. 2, Summer 1989)

The Newelletters: E. Gail Carpenter Describes Life on the Home Front, Part III (Charles William Sloan, Jr., ed., extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 11 No. 3, Autumn 1989)

The Newelletters: E. Gail Carpenter Describes Life on the Home Front, Part IV (Charles William Sloan, Jr., ed., extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 11 No. 4, Winter 1988-1989

Uncle Sam Wanted Them Too! Women Aircraft Workers in Wichita During World War II (Judith R. Johnson, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 17 No. 1, Spring 1994)

World War II and the American Home Front (Marilyn M. Harper, October 2007)

Rosie The Riveter On The Homefront During World War 2

Books

rori/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Aug-2024