|

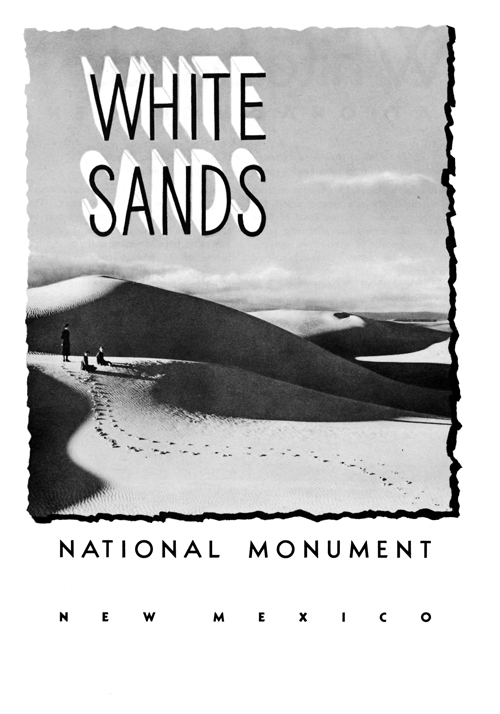

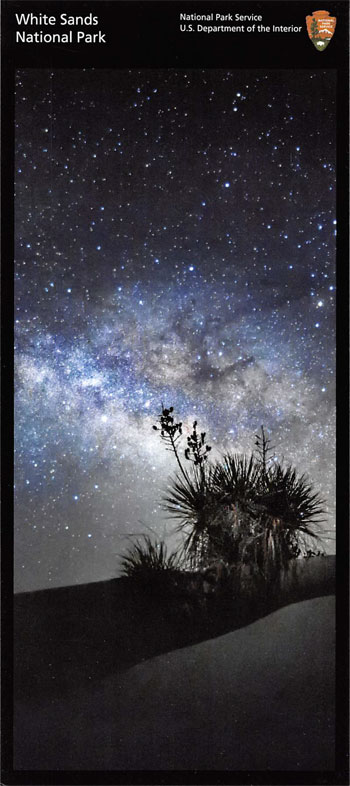

White Sands National Park New Mexico |

|

NPS photo | |

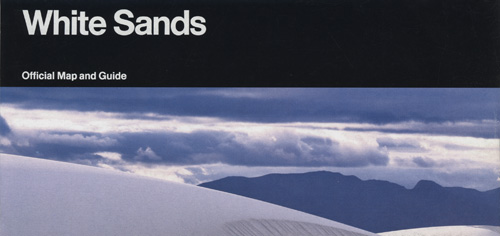

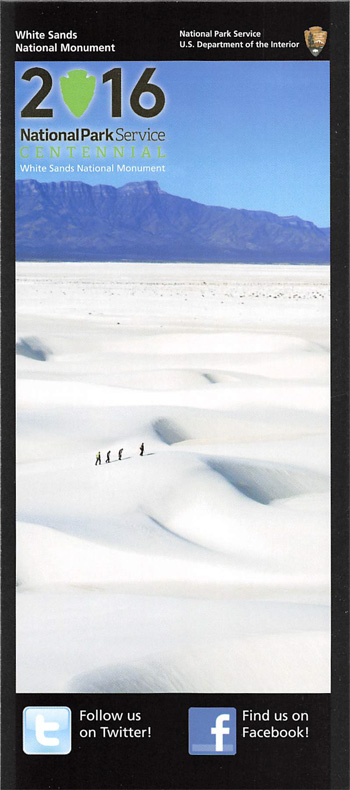

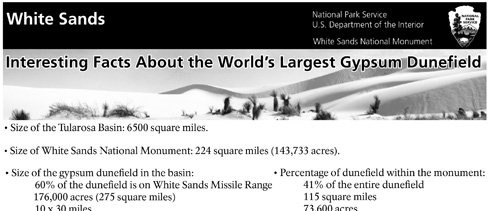

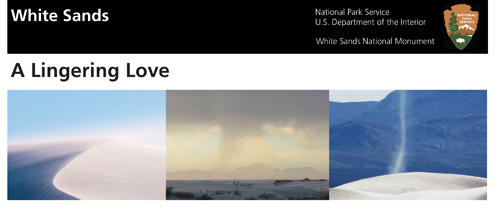

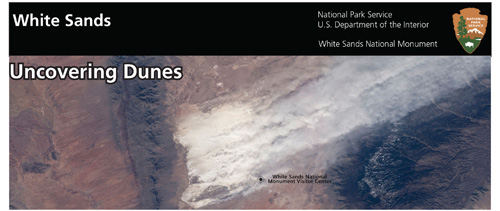

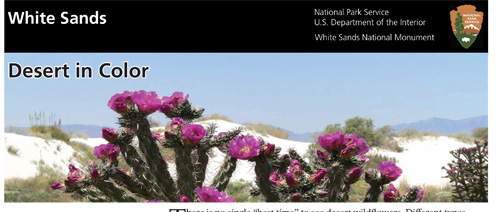

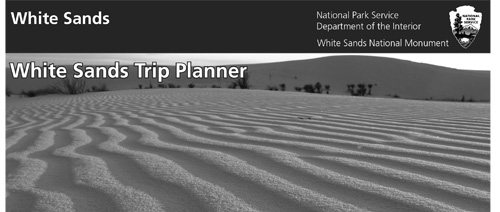

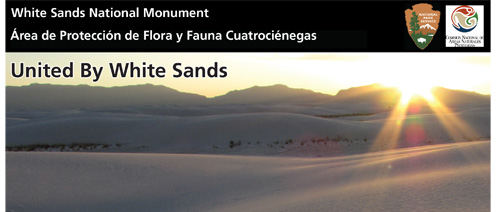

Like a mirage, dazzling white sand dunes shimmer in the tucked-away Tularosa Basin in southern New Mexico. They shift and settle over the Chihuahuan Desert, covering 275 square miles—the largest gypsum dunefield in the world. White Sands National Monument preserves more than half of this oasis, its shallow water supply, and the plants and animals living here.

Como un espejismo, las deslumbrantes dunas de arenas blancas brillan, enclavadas en la cuenca de Tularosa al sur de Nuevo México. Se mueven y se asientan sobre esta porción del desierto chihuahuense, cubriendo 700 kilómetros cuadrados—siendo las dunas de yeso más grandes del mundo. White Sands National Monument conserva más de la mitad de este oasis, su suministro de aguas poco profundas y las plantas y los animales que ahí habitan.

Paths to Survival / Estrategias de supervivencia

GROW FAST

Sand verbena survives because it flowers and disperses seeds in one growing

season. It also quickly spreads shallow roots. New plants emerge as passing

dunes bury older plants.

CRECER RÁIDO

La verbena sobrevive porque florece y dispersa sus semillas en una sola

temporada de crecimiento. También extiende raíces adventicias poco profundas.

Las plantas jóvenes emergen mientras las dunas mueven y entierran a las verbenas

viejas.

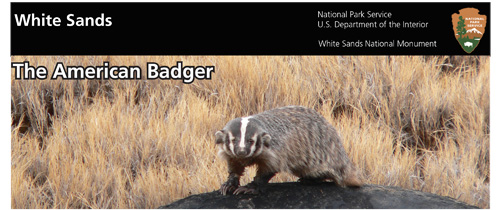

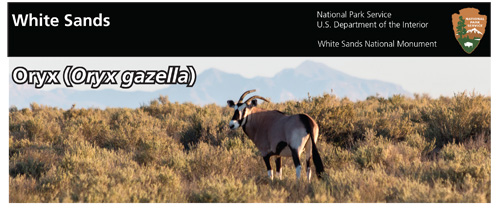

CHANGE COLORS

The bleached earless lizard and Apache pocket mouse are a lighter color than the

same species in the nearby desert. Their lighter color reflects heat, which

keeps them cooler and hides them better.

CAMBIAR DE COLOR

Las chivitas de lluvia y los ratones de abazones que viven dentro de las dunas

tienen un color más claro que los ejemplares de la misma especie que viven fuera

de este ecosistema. Su coloración más clara refleja el calor, los mantiene más

frescos y los oculta mejor.

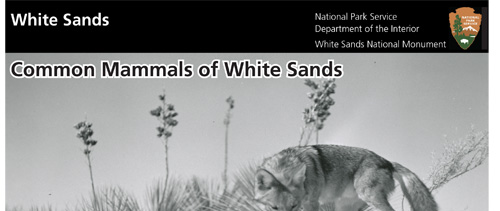

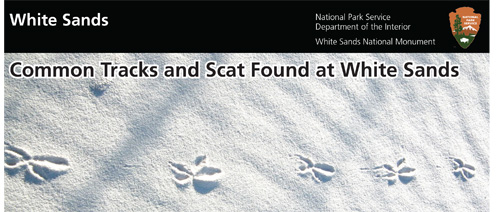

GO OUT AT NIGHT

A motion-detecting camera shows a kit fox in action, maybe chasing a mouse. Like

many desert animals, the fox comes out at night when the air is cooler. Look for

its tracks during the day.

SALIR DE NOCHE

Una camara de detección de movimiento muestra a esta zorrita del desierto en

acción, tal vez siguiendo a un ratón. Como muchos animales del desierto, la

zorrita sale de noche cuando el aire es más fresco. Busque sus huellas durante

el día.

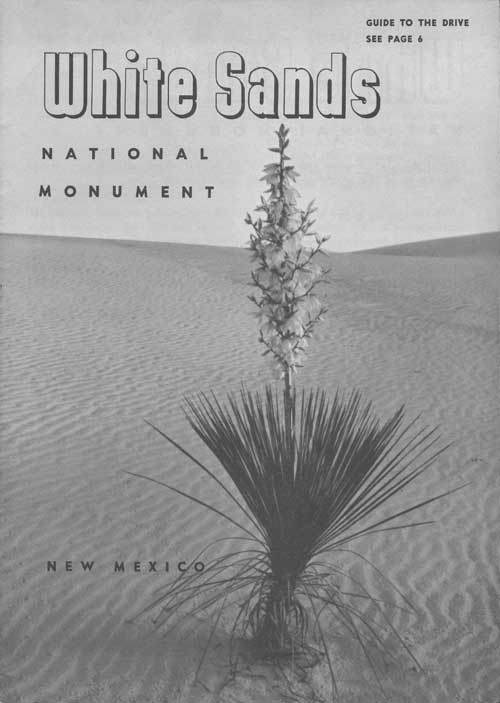

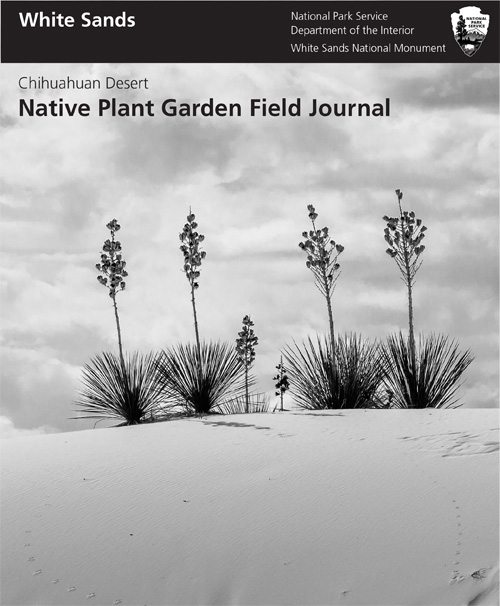

GROW TALL

As sand buries a soaptree yucca, its stem grows longer to keep new leaves above

the sand. But after the dune moves on, an exposed yucca like the one above will

soon fall over and die.

CRECER ALTO

El tallo del cortadillo crece más largo para mantener las hojas nuevas por

encima de la arena según la duna lo va enterrando. Pero una vez que la duna se

mueve, un cortadillo expuesta, como la de arriba, pronto caerá y morirá.

HOLD ON

A few shrubs like skunkbush sumac grow dense, deep roots that help form a

pedestal after the dune moves on. Kit foxes dig their dens in pedestals; other

animals find shelter here too.

SOSTENERSE

Unos cuantos arbustos, como el lambrisco, tienen raíces densas y profundas que

les ayudan a formar un pedestal una vez que se desplazan las dunas. Las zorritas

del desierto cavan sus madrigueras en estos pedestales. Otros animales

encuentran aquí un refugio.

People of the Tularosa Basin / Los habitantes de la cuenca de Tularosa

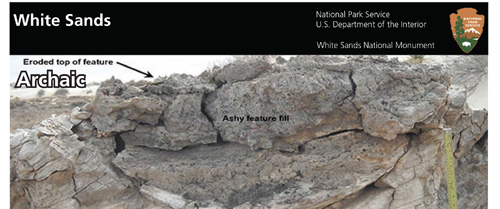

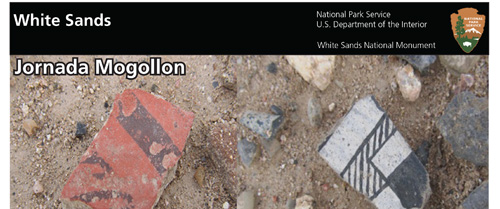

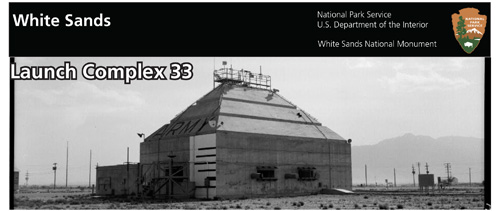

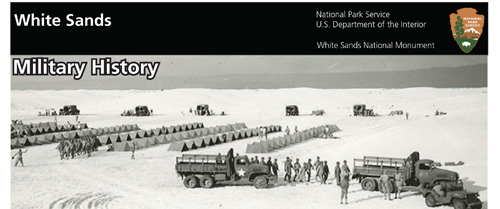

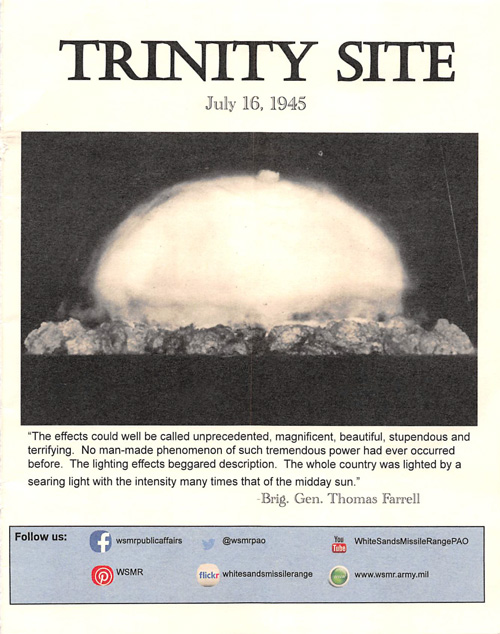

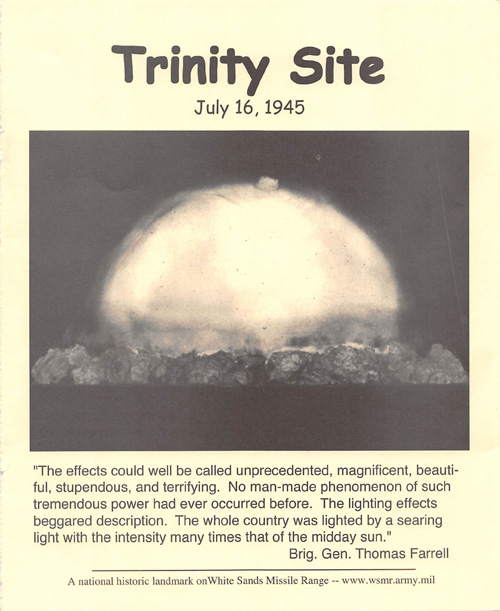

People arrived in the Tularosa Basin after the last ice age ended 11,000 years ago. The Jornada Mogollon were the first to farm the area, and lived here until drought forced them out in the 1300s. American Indians returned in the 1600s and European Americans came in the late 1800s. Soon the railroad rolled in—and so did settlers. Residents of Alamogordo promoted the idea of White Sands National Monument, which President Herbert Hoover proclaimed in 1933. During World War II, the US military tested weapons in the dunefield beyond the park. In 1945, the first atomic bomb was detonated at Trinity Site, 100 miles north of here.

Los primeros pobladores llegaron despues de que terminó la ultima era de hielo hace 11,000 años. La gente de la cultura llamada Jornada Mogollón fueron los primeros agricultores. Vivieron aquí hasta que la sequía los forzó a emigrar durante el siglo XIV. Los indígenas regresaron en el siglo XVII y los euro-americanos arribaron a finales del siglo XIX. Pronto llegó el ferrocarril y con él, los pobladores. Fueron los residentes de Alamogordo quienes promovieron la idea del White Sands National Monument, el cual fue establecido en 1933 por el presidente Herbert Hoover. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el ejército estadounidense probó armas en el área de dunas que está fuera de los limites del parque nacional. En 1945, la primera bomba atómica fue detonada en el lugar "Trinity Site", 160 kilómetros al norte de aquí.

Exploring White Sands / Exploración de White Sands

The Why of White Sands

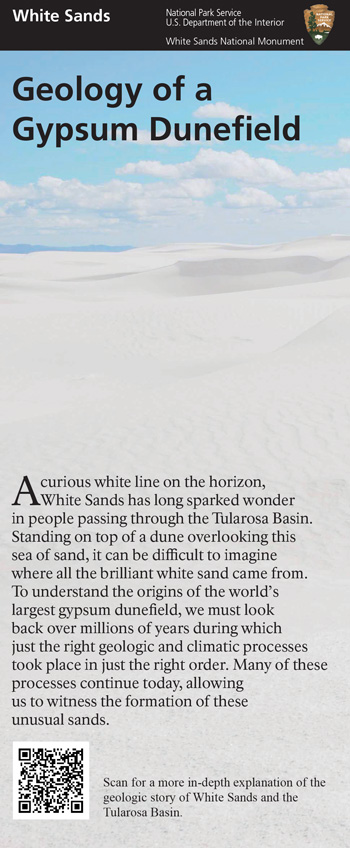

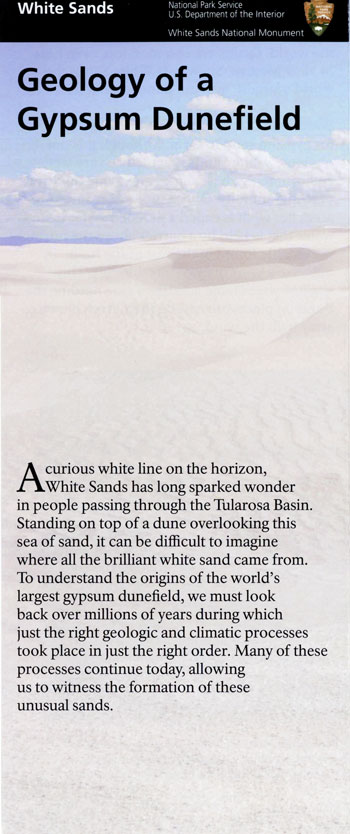

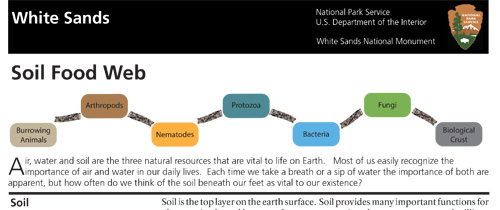

GYPSUM FROM AN ANCIENT SEA

When the Permian Sea retreated millions of years ago, it left behind deep layers

of gypsum. Mountains rose and carried the gypsum high. Later, water from melting

glaciers dissolved the mineral and returned it to the basin. Today, rain and

snow continue the process.

WIND AND WATER POWER

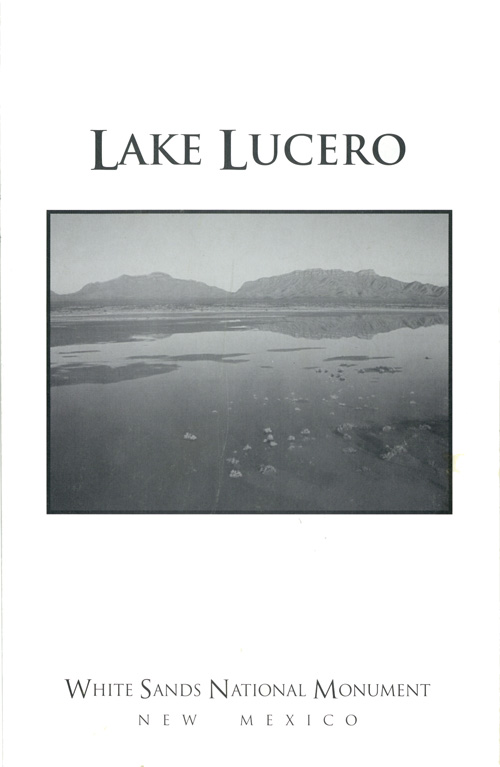

For thousands of years in shallow lakes like Lake Lucero, wind and sun have

separated the water from the gypsum and formed selenite crystals. Wind and water

break down the crystals making them smaller and smaller until they are sand.

Steady, strong southwest winds keep gypsum sand moving, piling it up and pushing

dunes into various shapes and sizes.

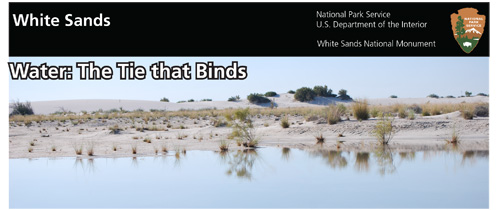

GLLUE FROM BELOW

Beneath your feet is the glue that holds this vast dunefield

together—water, inches below the surface. Compared to other dune types,

gypsum dunes remain moist during the longest droughts. This moisture prevents

the dunes from blowing away. Water becomes older and saltier toward the center

of the dunefield. Scientists are working to understand this change and other

phenomena of this shimmering land.

La evolución de White Sands

YESO DE UN MAR PREHISTÓRICO

Cuando disminuyeron las aguas del mar en el periodo pérmico, hace millones de

años, dejaron tras de sí profundas capas de yeso. Despues las montañas se

empezaron a elevar, y con ellas, el yeso. Posteriormente, el agua del deshielo

de glaciares disolvió el mineral y lo regresó a la cuenca. Hoy, la lluvia y la

nieve continúan el proceso.

EL VIENTO Y EL AGUA

Durante miles de años en lagunas poco profundas como lago Lucero, el viento y el

soi nan separado ai agua dei yeso, formándose así cristales de selenita. El

viento y el agua rompen los cristales haciéndolos cada vez más pequeños hasta

que se convierten en arena. Los constantes y fuertes vientos del suroeste

mantienen en movimiento a la arena de yeso, acumulándola y forzando las dunas a

que tomen diversas formasy tamaños.

INSÓLITO PEGAMENTO

Bajo sus pies se encuentra una especie de "pegamento" que mantiene unidas estas

enormes dunas—ei agua—a tan soio centimetros de la superficie.

Comparadas con otros tipos de dunas, las dunas de yeso permanecen húmedas

durante las más largas sequías. Esta humedad evita que se las lleve el viento.

El agua se torna más añeja y salada hacia el centro de las dunas. Los

cientificos siguen sus investigaciones para entender este cambio y otros

fenómenos de esta tierra resplandeciente.

Surprising Sand / Arenas sorprendentes

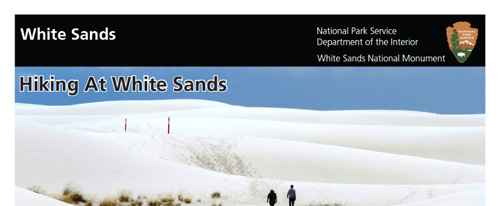

Gypsum dunes are firmer and cooler than other types of dunes. Many people enjoy sledding on these unusual dunes.

Las dunas de yeso son más firmes y frescas que otros tipos de dunas. Muchas personas desfrutan deslizarse en trineo.

Plan Your Visit

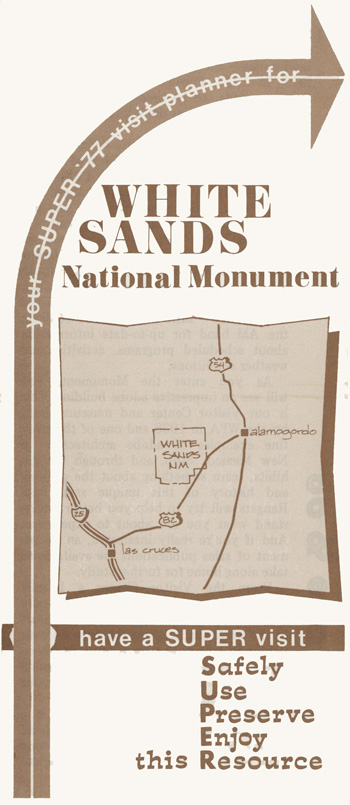

(click for larger map) |

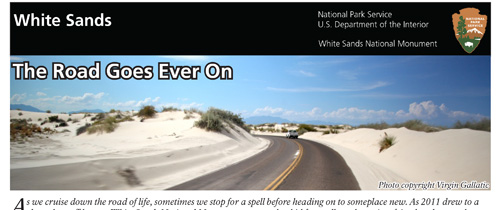

The entrance to White Sands National Monument is on US 70, 15 miles southwest of Alamogordo and 54 miles east of Las Cruces. Camping and lodging are available in Alamogordo and nearby areas. Ask at the visitor center about backcountry camping.

At the visitor center, view exhibits and a movie about the monument. Ask about park programs and ranger-led activities, and visit the bookstore and gift shop.

The visiter center is the only place to fill water containers.

Follow Dunes Drive into the heart of the dunes. Roadside exhibits and self-guiding trails show you secrets of the white sands. Relax at the picnic areas, which have shade, tables, grills, and restrooms—but no water.

Accessibility

We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For

information go to the visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our

website.

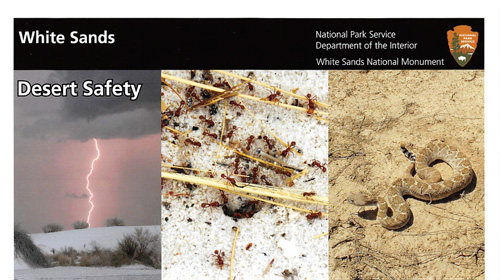

For a Safe Visit

Always keep landmarks in sight—don't get lost! • Carry water, even

when walking a short distance. No water is available beyond the visitor center.

• Wear sunscreen, sunglasses, and a hat. • Do not tunnel into dunes;

they can collapse and suffocate you. • Sled away from road. • Watch

out for heavy traffic in picnic areas. • Lock your vehicle and keep

belongings out of sight.

Regulations

Federal law protects all archeological and natural objects. • Pets must be

leashed. • Do not drive or park on dunes or interdunal areas. • For

firearms regulations see the park website.

Closed During Testing

White Sands Missile Range surrounds the monument. For public safety, the

monument and US 70 between the monument and Las Cruces may be closed during

missile range tests. Closures average twice a week for one to two hours. The

National Park Service and the Department of Defense appreciate your cooperation

and patience.

Emergencies call 911

Información para su visita

La entrada está en la autopista US 70, 24 km al suroeste de Alamogordo y 86 km al este de Las Cruces. Busque alojamiento o camping en Alamogordo.

En el centro de visitantes, vea las exposiciones y una pelicula para orientarse. Pregunte sobre actividades dirigidas por los guardaparques.

Llene sus botellas de agua en el centro de visitantes. Es su ultima oportunidad.

Siga el Dunes Drive hacia el centro de las dunas. Las exhibiciones al borde del camino y los senderos autoguiados le muestran los secretos de las arenas blancas. Relájese en las áreas de picnic que cuentan con sombra, mesas, asadores y letrinas—pero recuerde que no hay agua.

Accesibilidad

Nos esforzamos para que nuestras instalaciones, servicios y programas sean

accesibles para todos.

Sugerencias para su seguridad

¡No se pierda! Mantenga siempre a la vista los puntos de referencia del

horizonte. • Lleve agua consigo incluso cuando camine una distancia corta.

Pasando el centro de visitantes, ya no encontrará agua potable. • Use

bloqueador, lentes de sol y sombrero. • No excave túneles en las dunas ya

que se pueden colapsar y sofocarlo. • Disfrute su trineo alejado de los

autos. • Cuidese del tráfico en las áreas de picnic. • Cierre bien su

vehiculo y mantenga sus pertenencias fuera de la vista.

Reglas

Las leyes federales protegen todos los objetos arqueológicos y naturales. •

Las mascotas deben sujetarse con una correa. • No maneje ni se estacione en

las áreas entre las dunas. • Para obtener más información sobre las

regulaciones de armas de fuego, visite la página web de White Sands.

Se cierra durante pruebas de misiles

Una base del ejército rodea este parque nacional. Por la seguridad del público,

se cierra la autopista US 70 entre White Sands y Las Cruces durante las pruebas

de cohetes. El cierre ocurre dos veces por semana en promedio, con una duración

de una a dos horas. El National Park Service y las autoridades militares le

agradecen su cooperación y paciencia.

En caso de emergencia, llame al 911.

Source: NPS Brochure (2018)

|

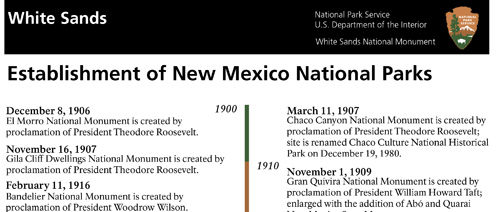

Establishment

White Sands National Park — December 20, 2019 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Brochures ◆ Site Bulletins ◆ Trading Cards

Documents

3-D radar imaging unlocks the untapped behavioral and biomechanical archive of Pleistocene ghost tracks (Thomas M. Urban, Matthew R. Bennett, David Bustos, Stuart W. Manning, Sally C. Reynolds, Matteo Belvedere, Daniel Odess and Vincent L. Santucci, extract from Scientific Reports, November 11, 2019, ©Springer Nature)

Ancient Human Presence Revealed At White Sands National Park: Researchers Push Back Date Of Human Arrival In North America Thousands Of Years (Kurt Repanshek, National Parks Traveler, September 23, 2021)

Climate Change Scenario Planning to Guide Research and Resource Management at White Sands National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/WHSA/NRR-2021/2261 (Pamela Benjamin, Gregor W. Schuurman, David Bustos, M. Hildegard Reiser, Tom Olliff and Amber Runyon, June 2021)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: White Sands NM Historic District/White Sands National Monument (1998, revised 2005)

Dunes and Dreams: A History of White Sands National Monument, Administrative History (HTML edition) Intermountain Cultural Resources Center Professional Paper No. 55 (Michael Welsh, 1995)

Extraordinary levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in vertebrate animals at a New Mexico desert oasis: Multiple pathways for wildlife and human exposure (Christopher C. Witt, Chauncey R. Gadek, Jean-Luc E. Cartron, Michael J. Andersen, Mariel L. Campbell, Marialejandra Castro-Farías, Ethan F. Gyllenhaal, Andrew B. Johnson, Jason L. Malaney, Kyana N. Montoya, Andrew Patterson, Nicholas T. Vinciguerra, Jessie L. Williamson, Joseph A. Cook and Jonathan L. Dunnum, extract from Environmental Research, Vol. 249, 2024)

Final Master Plan, White Sands National Monument, New Mexico (March 1976)

Footprints preserve terminal Pleistocene hunt? Human-sloth interactions in North America (David Bustos, Jackson Jakeway, Tommy M. Urban, Vance T. Holliday, Brendan Fenerty, David A. Raichlen, Marcin Budka, Sally C. Reynolds, Bruce D. Allen, David W. Love, Vincent L. Santucci, Daniel Odess, Patrick Willey, H. Gregory McDonald and Matthew R. Bennett, extract from Science Advances, ©2018The Authors, exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0)

Foundation Document, White Sands National Monument, New Mexico (January 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, White Sands National Monument, New Mexico (January 2016)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, White Sands National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2012/585 (October 2012)

Human footprints near ice age lake suggest surprisingly early arrival in the Americas (Lizzie Wade, Science, September 23, 2021)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: White Sands National Monument, 2012 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2013/676 (Philip S. Cook, July 2013)

Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands (Jeffrey S. Pigati, Kathleen B. Springer, Jeffrey S. Honke, David Wahl, Marle R. Champagne, Susan R.H. Zimmerman, Harrison J. Gray, Vincent L. Santucci, Daniel Odess, David Bustos and Matthew R. Bennett, extract from Science, Vol. 382, October 6, 2023)

Pre-K Junior Dunes Ranger Activity Book, White Sands National Monument (2016; for reference purposes only)

Junior Dunes Ranger Activity Book, White Sands National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

LiDAR Surveys of Gypsum Dune Fields in White Sands National Monument, New Mexico NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/CHDN/NRTR—2012/558 (Gary Kocurek, David Mohrig, Elke Baitis, Ryan C. Ewing, Virginia Smith and Aymeric Peyret, March 2012)

National Monuments Redesignated as National Parks: Insights for White Sands National Monument (Headwaters Economics, May 2018)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

White Sands National Monument Historic District (Betsy Swanson, July 1986)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, White Sands National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/WHSA/NRR-2017/1508 (Andy J. Nadeau, Kathy Allen, Kevin Benck, Anna M. Davis, Hannah Hutchins, Sarah Gardner, Shannon Amberg and Andrew Robertson, September 2017)

Natural Resources Management Plan for White Sands National Monument (October 1974)

Physical Resources Foundation Report, White Sands National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/NRR-2009/166 (Jeffrey Bennett and Douglas Wilder, November 2009)

Resources Management Plan and Environmental Assessment for White Sands National Monument (November 1986)

Springs, Seeps and Tinajas Monitoring Protocol: Chihuahuan and Sonoran Desert Networks NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1796 (Cheryl McIntyre, Kirsten Gallo, Evan Gwilliam, J. Andrew Hubbard, Julie Christian, Kristen Bonebrake, Greg Goodrum, Megan Podolinsky, Laura Palacios, Benjamin Cooper and Mark Isley, November 2018)

Story of the Great White Sands (Tom Charles, 1950)

The Geology of the White Sands of New Mexico (C.L. Herrick, extract from The Journal of Geology, Vol. 8 No. 2, February-March 1900)

The Natural History Story of White Sands National Monument Southwest Parks and Monuments Association Natural History Series No. 2 (Natt N. Dodge, 1971)

Vertebrate Paleontological Resources from National Park Service Areas in New Mexico (Vincent L. Santucci, Justin Tweet, David Bustos, Jim Von Haden and Phillip Varela, extract from New Mexico Museum of Natural History Bulletin 64, 2014)

Vibration investigation of the museum building at White Sands National Monument, New Mexico USGS Open-File Report 88-544 (Kenneth W. King, David L. Carver and David M. Worley, 1988)

Visitor Study, Summer 2012, White Sands National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR-2013/642 (Ally Begly, Beth Barrie, Lena Le and Steven J. Hollenhorst, March 2013)

Walking in mud: Remarkable Pleistocene human trackways from White Sands National Park (New Mexico) (Matthew R. Bennett, David Bustos, Daniel Odess, Tommy M. Urban, Jens N. Lallensack, Marcin Budka, Vincent L. Santucci, Patrick Martinez, Ashleigh L.A. Wiseman and Sally C. Reynolds, extract from Quaternary Science Reviews, Vol. 249, September 2020)

White Sands Geological Report Southwestern Monuments Special Report No. 5 (Vincent W. Vandiver, 1936)

White Sands National Monument (1938 National Park Service, US Department of Interior)

Books

whsa/index.htm

Last Updated: 02-Oct-2024