|

THE FIRST BATTLE OF MANASSAS

On a blistering hot July day in 1861 in northern Virginia, men who

for generations had been friends, fathers, and sons, brothers even, put

aside their bonds of brotherhood and blood and took up arms, to shed

that blood if they could. America had gone mad and gone to war with

itself.

Perhaps it was inevitable. Old animosities and antagonisms had

somewhat divided the interests and sympathies of the northern and

southern colonies even before they won their independence in another,

earlier war. Then, once they became the United States, events showed

just how much there was to separate them. Most especially, the issue of

slavery set them at odds, as the North eventually abolished bonded

servitude, while the states south of Mason and Dixon's line clung to it

not only for its labor system, but also as a symbol of a way of life.

Unfortunately for all, the issue became enmeshed with the struggle for

power in the national government. Seeing more and more "free" states

entering the Union, the "slave" states saw themselves at risk of

becoming a minority in representation—and power—in

Washington. When that happened, they feared, the national government

might strike to abolish slavery everywhere. The result could be

economic and social ruin for the South.

The election of 1860 brought Abraham Lincoln to the presidency at the

head of a new Republican Party avowedly opposed to the further spread of

slavery and implicitly in favor of its universal abolition if possible.

Though Lincoln promised before the election that he would not interfere

with slavery where it already existed, the storm of fear that swept the

South after his election left few willing to believe him. The only hope

for the South seemed to lie in secession, withdrawing from the Union to

create its own Southern, slaveholders' nation. In February 1861

representatives from the first six states to secede met and framed the

Confederate States of America, with Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as

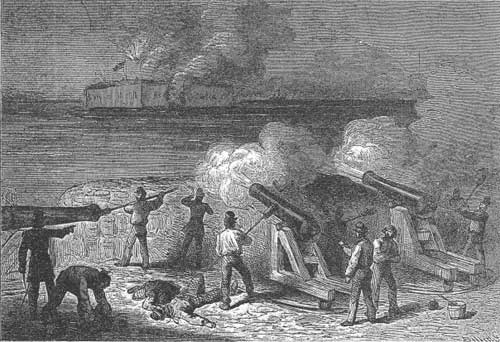

its president. Two months later, in an effort to evict United States

soldiers from their post on what was now Confederate soil, Southern guns

around Charleston Harbor in South Carolina opened fire on Fort

Sumter. It was a momentous step, the most fateful taken so far, and

everything that followed for the next four years was a result.

|

THE ATTACK ON FORT SUMTER. (LC)

|

Shock waves swept North and South alike. Surprisingly, Davis and his

government felt that they were fully justified in bombarding Fort

Sumter. After all, they were only trying to take back their own soil now

that South Carolina was part of a new "nation." Many in the South did

not expect the United States to be especially aggrieved over being shot

at. Moreover, Southern leaders—but not Davis—persuaded

themselves that the Yankees were too cowardly, too miserly, to expend

any blood or treasure on fighting back. Consequently, they were more

than surprised when a wave of anger and humiliation surged through the

North and when Lincoln on April 17 issued a proclamation calling out up

to 75,000 volunteers to put down the "rebellion." How dare Lincoln fight

back? Indeed, how dare he fight at all, since the South only took back

what belonged to it in the first place, or so Southerners reasoned.

Worse yet, by speaking of putting down a "rebellion," Lincoln declined

to recognize their right to withdraw from the Union, and then he went

even further by authorizing what could be the largest army ever

assembled 75,000 men, obviously intending to have it "invade" Southern

soil. To Confederates and to sympathizers in other Southern states not

yet seceded, the firing on Fort Sumter was an act of self-defense and

nothing more. But Lincoln's act, they now reasoned, constituted an

outright act of war.

As a result, in the weeks following Lincoln's proclamation other

slave states that had been wavering made their decision. Virginia,

Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina joined with the Confederacy. In

each state, as with those that had seceded earlier, among the first

acts after voting for secession was to seize United States armories,

arsenals, forts, and shipyards, and with them their weapons and

machinery. While this was important everywhere, nowhere was it as vital

as in the Old Dominion.

|

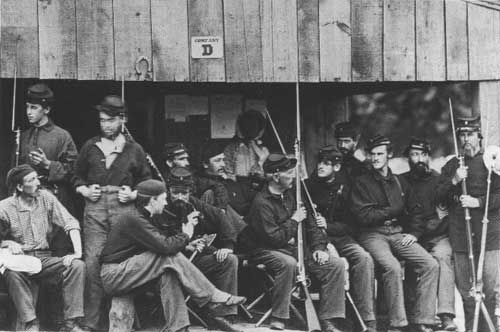

CONFEDERATE TROOPS LIKE THERE MEMBERS OF THE 1ST VIRGINIA INFANTRY

EAGERLY AWAIT THE COMING CONFLICT (VM)

|

Virginia would be the northeastern border of the new Confederacy.

Only the Potomac River separated it from Maryland, Washington, D.C., and

the Union. The shipyard at Norfolk was the finest in the country. More

important still, at Harpers Ferry, fifty miles up the Potomac from

Washington, the United States armory and arsenal were a major source of

rifles and weapons manufacturing equipment. But most important of all

was Virginia's strategic location and geography. Any invasion of the

Confederacy by those 75,000 volunteers of Lincoln's would naturally

come through the state. That meant that Virginia was destined to be the

first battleground, if any battles were to be fought. Moreover, the Blue

Ridge Mountains running roughly northeast to southwest in the middle of

the state neatly separated the eastern half of Virginia from the

Shenandoah Valley to the west. That valley ended at Harpers Ferry, and

an army could move up or down the valley virtually unseen. Yankees,

entering at the north, could suddenly appear somewhere in the heartland

of the state, behind Confederate lines, with potentially disastrous

results. Or Confederates could move north in the Shenandoah and find

themselves on the Potomac, ready to invade the North without having been

detected.

|

NEW FEDERAL RECRUITS SET UP ENCAMPMENTS THROUGHOUT THE WASHINGTON AREA.

SHOWN HERE ARE MEMBERS OF THE 1ST RHODE ISLAND INFANTRY. (LC)

|

All of this and more called for a sudden and dramatic shift of

Confederate attention to Virginia. Even before the state seceded,

Jefferson Davis sent emissaries to the Old Dominion's organized militia.

After secession, he immediately tried to cooperate with Governor John

Letcher in mobilizing that militia even while Davis began the task of

building an army of his own to oppose Lincoln's. While Davis worked,

Letcher's first significant step was to appoint a recently resigned

United States officer to take command of all state forces. He turned to

Robert E. Lee, a Virginian, a soldier of national reputation and a man

intimately acquainted with the ground below the Potomac. Even before the

first Confederate troops started to arrive, Lee, now a general, began

planning the defense of his beloved Virginia.

Lee and those advising him knew at a glance that they could not keep

the Yankees entirely out of Virginia. After all, only the Potomac River

separated the state from Washington, and the Unionists held the bridges

crossing the stream. Lee could try to resist a Federal crossing, but he

knew it would be nothing more than a delaying action. Instead, he looked

to suitable ground a little south of the Potomac, for places where the

geography would favor defending against an invasion. Other

considerations influenced his thinking at the same time. The Orange

& Alexandria Railroad connected Washington with the interior of the

Old Dominion. Invading enemies would naturally try to seize the line,

deny it to the Confederates, and use it themselves as a supply line on

an invasion. Lee must hold as much of that line as possible. Moreover,

at Manassas Junction the line connected with the Manassas Gap Railroad.

It stretched west across the Blue Ridge to the Shenandoah Valley. Lee

had to hold it, too, to preserve the possibility of shifting troops east

or west of the mountains to meet sudden threats.

|

PHILIP ST. GEORGE COCKE (VM)

|

|

THOMAS J. JACKSON (LC)

|

Thus circumstances demanded that Lee hold Manassas Junction at the

very least. Happily, just a few miles north of the junction ran a stream

called Bull Run. With banks too steep to ford just anywhere, it was

crossable only at a stone bridge on the road to Warrenton and at a

handful of fords. Fortify those crossings, reasoned Lee, and he could

stop an invader.

Almost as soon as Virginia seceded, Letcher sent Brigadier General

Philip St. George Cocke to take charge of starting the defenses. The

outlook did not look promising. He had only 300 men, no cannon, no

staff, and no experienced engineers to plan the defenses. But Cocke did

have imagination, energy, and dedication, and Lee standing behind him.

As soon as he could, Lee began to forward men and artillery to the

Manassas line. Meanwhile, all across the Confederacy men were

volunteering, and as soon as they could be organized Jefferson Davis sent

them to Virginia, often even before they had uniforms and weapons, and

almost always before they knew even the rudiments of training. They

could practice their drill and learn their commands once they arrived.

Meanwhile, out in the Shenandoah, Lee had to look to the defense of

Harpers Ferry, too. With troops being sent to the arsenal village,

someone had to take charge. The man Letcher chose to appoint was an

oddity-religious fanatic, hypochondriac, a stern disciplinarian who

survived ridicule and assassination threats from pupils when he taught

at the Virginia Military Institute-named Colonel Thomas Jonathan

Jackson. At once Jackson set about turning these raw recruits into

soldiers and the soldiers into the nucleus of the infant Army of the

Shenandoah.

Richmond could assign its own state militia commanders to start all

of this work, but as soon as Virginia became a new state in the

Confederacy and Jefferson Davis took over direction of military defense, it would

be up to him to select and assign overall commanders and to press

forward the work. From faraway Montgomery the president cast about for

the right men and did not have to look far. As soon as Virginia seceded

he inquired about the intentions of Lee and was pleased that he would

accept command of Virginia state forces. While a distinguished soldier,

Lee had little experience of command in combat, and Davis did not yet

look to him as a field commander.

Another Virginian, however, immediately came to mind. Joseph E.

Johnston had an excellent career in the old United States Army and had

won battlefield promotions in the Mexican War. Moreover, he was a

Virginian and could be expected to know the country. He was a small,

slight man, who looked every inch a soldier. And yet, in Virginia

parlors people told stories about him. He had a fine reputation as an

excellent marksman, yet when he went shooting with friends he seemed

always hesitant to shoot at the quail they hunted.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE ARMIES MOVE TO MANASSAS

By late spring 1861 General P.G.T. Beauregard's Army of the Potomac

takes up positions around Manassas Junction. On July 16, General Irvin

McDowell's Army of Northeastern Virginia moves out from Washington,

D.C., with hopes of capturing the junction. To meet this threat General

Joseph E. Johnston moves his Army of the Shenandoah to Manassas,

Johnston is able to elude a Union force under Genera! Robert Patterson

and uses the Manassas Gap Railroad to transport his force rapidly to

Beauregard's assistance.

|

The birds were always too high, the sun in his eyes, or the barking

dogs too distracting. While others banged away, often missing but

still bagging some birds. Johnston came back with an empty game sack.

But at least his reputation remained intact. He had not missed a single

shot because he had not taken one. Would he be the same as a

general?

If there were fears that Johnston

might be too reluctant to act in the Shenandoah's defense, others might

also worry that Beauregard would act too quickly or rashly. Only time

would tell.

|

Davis assigned Johnston command of the growing forces in the

Shenandoah. Meanwhile, to command the army being formed on the Manassas

line, there was almost never a question as to who should lead it.

General P. G. T. Beauregard was the darling of the Confederacy after his

capture of Fort Sumter. The South had fought one "battle" such as it

was. If there was to be another, who should command in it except the victor?

Beauregard came from Louisiana, was short but very fit and military, and

took pains to present as fine an appearance as possible. He was an

excellent engineer and much thought of in the old army, having been

superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point when the secession

crisis came. He was also vain, prickly, and given on occasion to

fantastical thinking. If there were fears that Johnston might be too

reluctant to act in the Shenandoah's defense, others might also worry

that Beauregard would act too quickly or rashly. Only time would

tell.

Nor were Johnston and Beauregard the only untried men upon whom the

Confederacy would depend. The soldiers themselves, farm boys from

Georgia, students from South Carolina, clerks and shopkeepers from

Alabama, street toughs from Louisiana, and more, all were unskilled and

inexperienced at war. The generals worked tirelessly to turn them into

soldiers even as they commenced the construction of their defenses to

retard a Yankee advance. Young volunteers who enlisted for a quick

glorious fight in order to return home as heroes quickly chaffed under a

routine that included rising at 5 A.M., drill half an hour later,

breakfast at 6, guard practice at 7, drill at 8, more drill at 10:30

until I P.M., drill again at 3, and dress parade at 6.

|

P.G.T. BEAUREGARD (LC)

|

Then came the matter of their organization and who should command

them. Volunteers formed into companies of about 100 and elected their

own captains and lieutenants. State authorities joined ten companies to

form a regiment and allowed the company officers to elect the regimental

colonel, or else the governors appointed them. Now Johnston and

Beauregard would form brigades composed of three or more regiments, as

much as possible keeping outfits from the same state together. But when

it came to selecting men to command those brigades—they would be

commissioned colonels or brigadier generals—the decision lay with

Jefferson Davis. It helped that late in May Davis and the government

shifted from Montgomery to Richmond to be nearer the scene of action,

and now the president could see personally to the organization of his

armies' high command. Eventually Johnston would have five brigades:

Virginians commanded by Jackson, Alabamians and Mississippians under

Colonel Edmund Kirby Smith, Alabamians led by Brigadier General Barnard

E. Bee, Georgians under Colonel Francis Bartow, and a mixed brigade

answering to Colonel Arnold Elzey. By mid-July the Army of the

Shenandoah numbered perhaps 12,000 or thereabouts and represented almost

every state in the Confederacy. Beauregard commanded somewhat more,

around 20,000, divided eventually into seven brigades. Cocke commanded

one. Colonel Theophilus Holmes took another, as did the crusty Richard

S. Ewell of Virginia. and fellow Virginian Colonel Jubal A. Early, with

his quaint lisp. Milledge L. Bonham of South Carolina led fellow

Palmettos, as did Colonel David R. Jones. The hale and hearty James

Longstreet, though he hailed from South Carolina, received command of a

brigade of Virginians. The two armies combined totaled close to 35,000

men, with the Manassas Gap Railroad connecting them. If either was

attacked, the other could use the line to come in aid. If both were

attacked simultaneously, however, the railroad would be of no use to

them.

|

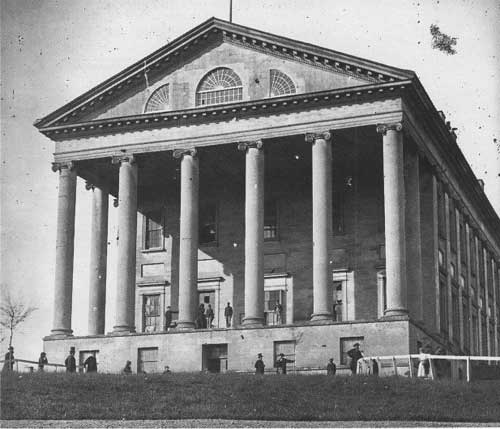

THE CONFEDERATE GOVERNMENT HAD ORIGINALLY BEEN SEATED IN MONTGOMERY,

ALABAMA, BEFORE TRANSFERRING TO RICHMOND, VIRGINIA. ON MAY 20. 1861, THE

VIRGINIA STATE CAPITAL ALSO BECAME THE CAPITAL OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES

OF AMERICA. (LC)

|

|

RICHARD S. EWELL (LC)

|

|

JUBAL A. EARLY (LC)

|

That was essentially what Washington wanted to do. Winfield Scott sat

heavily in his swivel chair at the War Department, more than seventy

years old, too fat and infirm even to mount a horse. Yet he was still a

magnificent soldier, and Abraham Lincoln looked immediately to him to

cast a plan for taking Virginia and Richmond quickly and putting down

the rebellion. Scott was a Virginian himself, though his loyalty to the

Union never wavered, and he saw at once the same geographical features

that Davis and his generals appreciated. Especially once Richmond

became the Confederate capital, authorities in Washington became fixed

upon the necessity of capturing it. Take Richmond, they felt, and the

rebellion would wither. All that stood between them and that objective

were Beauregard at Bull Run and Johnston in the Shenandoah.

From all across the Union came the regiments filled with fresh-faced

young men anxious to see some adventure and avenge the insult to the

Stars and Stripes. Within weeks of the outbreak of war, Washington

itself became an armed camp, even its public buildings swelling with

uniformed men and the White House grounds themselves hosting soldiers. The

population of the city almost doubled as the streets teemed with the

sounds of fifes drums, and marching feet. Scenes from south of the

Potomac were repeated here and elsewhere as the officers went about the

often grueling work of turning rustics into soldiers overnight.

While his burgeoning army drilled, Scott and his advisers studied

their maps and addressed the challenge before them. They saw the

Manassas Gap Railroad. They saw the potential use of the Shenandoah

Valley as an avenue of invasion and a back door to Richmond. They saw

the defenses going up along Bull Run and in advance of the stream.

Quickly Scott knew that he, too, must form two armies, and that they

must move in unison, with overwhelming strength, to press the Rebels and

not allow hem to use the rails to reinforce one another. Do that, push past

the Bull Run line, move into the Shenandoah and then turn east at one of

the Blue Ridge gaps, and Richmond would be easy prey.

Early in June Scott assigned Brigadier General Robert Patterson to

the task of forming an army in and around Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

When it was ready, he was to march south across Maryland and push across

the Potomac to take Harpers Ferry and defeat or at least fully occupy

Johnston's Confederates. Meanwhile, a substantially larger army took

shape in Washington. Once more companies became regiments, and regiments

became brigades. Taking organization a step further than the

Confederacy to provide a more efficient chain of command, these Yankees

combined two or more brigades to form army divisions. The first division

went to Brigadier General Daniel Tyler, 62, a longtime veteran. The

second division went to Brigadier General David Hunter, a man of

Southern heritage who stayed loyal to the flag. Samuel P. Heintzelman

received command of the third division, in spite of the bemused or

befuddled expression that seemed always on his face, and because of his

excellent combat record in Mexico. Theodore Runyon led the fourth

division, made up of untrained men who would not be used in the

campaign, and Dixon S. Miles, a notorious inebriate, commanded the fifth

division.

To lead the brigades commanded by these men, Washington commissioned

a mixed bag of characters, some already well known, others destined for

fame: William B. Franklin, Orlando B. Willcox, Ambrose Burnside, William

T. Sherman, Andrew Porter, Erasmus Keyes, and more. But the real

attention went to the selection of a commander for this army as a whole.

Scott himself could not lead it, of course. And the North did not, as

yet, have any established military hero like Beauregard to turn to.

Scott preferred old veteran Joseph K. Mansfield, but once more politics

intervened. An obscure major on staff duty in the adjutant general's

office, a man who had never led so much as a company in action, had

powerful friends.

|

WASHINGTON, D.C'S PREWAR POPULATION OF 60,000 RAPIDLY GREW AS NEW

RECRUITS BEGAN TO ARRIVE IN THE CITY IN APRIL 1861. AS SPACE IN WHICH TO

HOUSE THE MEN BECAME A PROBLEM, SOME WERE QUARTERED IN THE CAPITOL WHOSE

DOME WAS STILL UNDER CONSTRUCTION. (LC)

|

|

DANIEL TYLER (LC)

|

|

ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY SHOWS UNION TROOPS PREPARING FOR

BATTLE.

|

|

|