|

It was about 12:30 when Johnston and Beauregard arrived on Henry Hill

to survey the situation in person. Johnston himself took command of a

part of the now leaderless and shocked Fourth Alabama and led it to the

right of Jackson's line on Henry Hill. Now some of the scattered and

confused men of Evans's shattered command began to reform around the

nucleus of Jackson, and within minutes the Confederate line grew and

strengthened in numbers and resolve, though still heavily outnumbered by

the enemy. Had the Yankees pushed their advance vigorously once

Heintzelman arrived, they probably could have walked over Henry Hill,

Jackson included. By waiting too long, they gave the Confederates time,

and now it would cost them.

|

STATUE OF STONEWALL JACKSON AT

MANASSAS NATIONAL BATTLEFIEDL PARK. (NPS)

|

Now Johnston left Beauregard at the front and himself rode back to

the rear to find more reinforcements and channel them toward the scene

of fighting. Rapidly more men came, first the odd ex-governor of

Virginia, William Smith, called "Extra Billy" thanks to his predilection

for adding "extra" items to state appropriations. He brought three

companies of the 49th Virginia, along with portions of other commands

that he found along the way, men not afraid to follow him even though he

held an umbrella over his head while riding, to ward off the sun. As

Smith and others went into line around 3 P.M., the Henry Hill line was

almost complete, but barely more than 3,000 strong. The timing could not

have been better for now at last the Yankee attack appeared to be

renewing, as two batteries rolled down across Young's Branch and moved

up the slope of Henry Hill, preparing to soften the Confederate line

prior to an infantry assault.

It was a foolish move for McDowell to make, for he sent the artillery

forward with no infantry support. The cannoneers were isolated, alone,

but unlimbered their guns and opened fire, initially concentrating on

Confederates near the house of the widow Judith Henry atop the hill. She

had refused to leave her home, and one of the first shots from the

cannon almost severed one of her feet. She lay dying for the rest of the

day, and afterward her son threw himself face down on the ground outside

the house crying, "They've killed my mother."

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

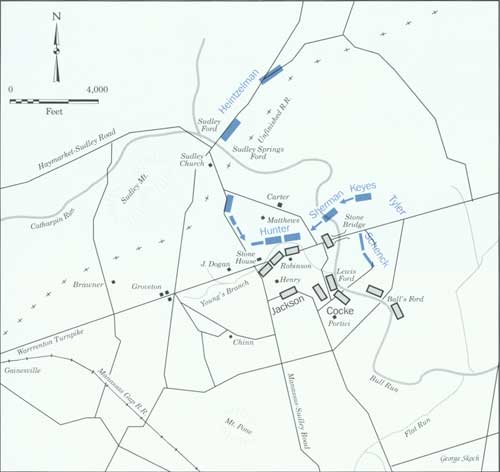

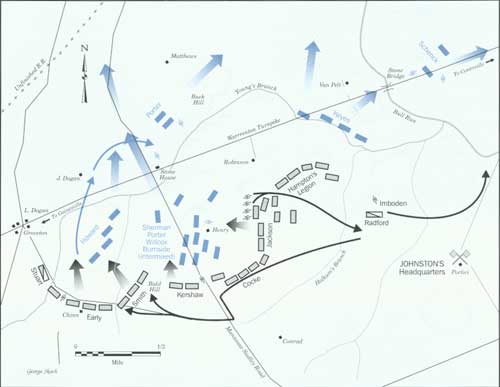

THE CONFEDERATES RALLY ON HENRY HILL (12:30-2:00 P.M.)

As the Confederates retreat from the fighting on Matthews Hill, Brigadier

General Thomas J. Jackson moves his five Virginia regiments onto Henry

Hill. Believing that the Southern army is in full retreat and that the

battle is won, General McDowell orders his men to halt and reorganize

along the Warrenton Turnpike. This lull in the fighting allows the

Confederates time to strengthen their position on Henry Hill.

|

The Union artillery then dueled with Confederate batteries less than

300 yards away for nearly an hour as McDowell continued to take his

time, all the while squandering his early advantage. Then at last,

instead of sending his whole line forward and taking advantage of his

strength, he made the mistake that generals would commit again and again

throughout the entire war. He sent forward only one regiment at a time,

first the colorful Eleventh New York "Fire Zouaves." As they came

abreast of the two batteries, Jackson's line on the hill arose and sent

a withering volley into them. Volley after volley crashed into them, and

they finally fell back, leaving the cannon unprotected.

Just now, Jeb Stuart's Virginia cavalrymen came on the scene, putting

the retreating zouaves to rout on the Sudley Road. Then one of Jackson's

regiments rushed forward. It was the Thirty-third Virginia, men who

happened to be wearing non-descript uniforms of varying colors. They

rushed toward the guns, and Griffin at first delayed firing on them,

warned by his superior that they might be fellow Federals. They

discovered too late their mistake. The Virginians cut down more than

fifty of their battery horses, making it impossible to get the guns

away, and captured two fine cannon as the artillerymen scurried away for

their lives. Seeing this success, Jackson ordered his whole line forward

to clear the hill of Yankees, taking the other nine guns of Griffin's

and Ricketts's batteries. At last the Confederates could sense that they

had a chance of gaining the upper hand on a day that at first looked to

be going all for McDowell.

|

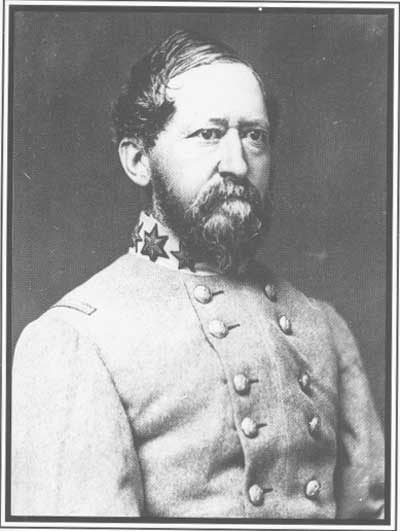

AS THE DISORGANIZED CONFEDERATE FORCES MILLED ABOUT ON HENRY HILL,

CONFEDERATE COMMANDER JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON RALLIED THE MEN BY PERSONALLY

LEADING REMNANTS OF THE FOURTH ALABAMA BADE INTO THE FRAY. (BL)

|

Beauregard ordered a general attack, and as his line swept forward,

the little general cried, "The day is ours! The day is ours!" In fact,

the outcome was still very much open to whichever side took best

advantage of its opportunities. McDowell stopped the Confederate

advance, regrouped his own line, and then started sending in additional

attacks of his own, though each time repeating the mistake of making

them piecemeal rather than in overwhelming force. Still, more regiments

were constantly arriving from the Sudley Ford crossing, and each went

into line on the Federal right, gradually extending it below Henry Hill.

In time the Federals would be able simply to overlap the Confederate

line and force Beauregard to withdraw for fear of being surrounded or

cut off from Manassas Junction.

|

CURRIER AND IVES PRINT GALLANT CHARGE OF THE ZOUAVES AND DEFEAT OF

THE REBEL BLACK HORSE CAVALRY. (LC)

|

For the next two hours the battle seesawed back and forth with

casualties mounting and no clear indication of who was going to win.

Time after time the lost cannon of Griffin and Ricketts were retaken by

the Federals, then captured again by the Confederates, each time before

the guns could be manhandled to the rear by either side. And now,

regardless of what Bee meant with the Stonewall remark, Jackson proved

indeed to be an immovable object. When Sherman came into the Yankee line

he sent an attack up Henry Hill that slammed into the Virginians and was

stopped cold. Once more confusion over uniforms caused hesitation, for

Sherman's Second Wisconsin wore gray, and Jackson's men at first were

reluctant to fire on them, while fellow Yankees did shoot at them,

thinking them to be Rebels. Eventually, however, the Confederates beat

Sherman back.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

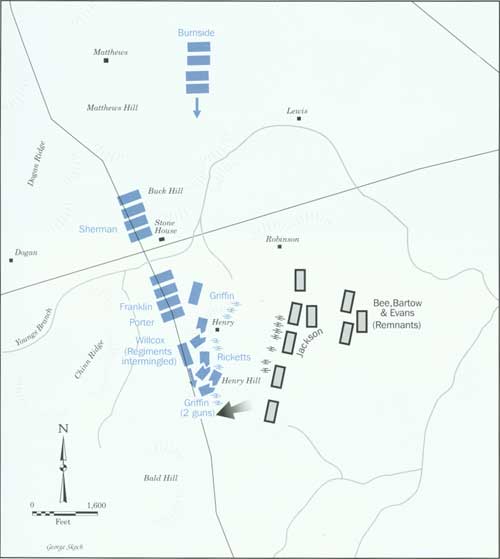

THE CAPTURE OF GRIFFIN'S GUNS (2:00-3:30 P.M.)

With the Confederate line stabilizing on Henry Hill, General McDowell orders

Captains James Ricketts's and Charles Griffin's artillery batteries to

Henry Hill. Without infantry support the Federal cannons are easy

targets for Confederate sharpshooters. Captain Ricketts temporarily

silences the sharpshooters, and the two sides then engage in a

close-range artillery duel. Captain Griffin moves two of his cannons to

the right of the Union line in the hopes of forcing the Confederates

from their strong position on the southern edge of the hill. However,

Griffin's guns are unsupported and in the confusion of battle a

Confederate regiment is able to advance within 75 yards of the guns. The

Southerners fire a point-blank volley at the battery, forcing Griffin to

abandon his position and leaving his guns to the fast-advancing

Confederates. The capture of Griffin's guns was the first success of the

day for the Southern army and the turning point of the battle.

|

Then Sherman sent in the Seventy-ninth New York, called the

Highlanders thanks to their plaid pants and tartans. Jackson was ready

for them. "The first fire swept our ranks like a quick darting

pestilence," said one of the Yankees. Colonel James Cameron, brother of

Lincoln's secretary of war, Simon Cameron, fell mortally wounded early

in the assault. Then many of the men mistook the Confederate

flag—red, white, and blue—hanging limply on a staff, for the

Stars and Stripes. They held their fire thinking that Jackson might be

on their side. The delay proved fatal. And as Confederate fire drove

them back in confusion, the Sixty-ninth New York—to be called the

"Fighting Sixty-ninth"—just coming up, encountered the same wall

of lead.

|

THE CAPTURE OF RICKETTS'S BATTERY PROVED A PIVOTAL MOMENT IN THE

STRUGGLE FOR HENRY HILL. (PAINTING BY SYDNEY KING, COURTESY OF NPS)

|

Each time one of these regiments fell back, it jumbled the main

Federal line as the fleeing attackers passed through. Sometimes men did

not stop on the command to regroup but simply kept running in

near-panic. Heintzelman tried to stop them, but then he went out of the

battle with a painful wound. Indeed, so many officers were falling that

there was no one for some of the men to turn to, and so they simply

wandered back toward Sudley Ford, getting in the way of reinforcements

still on the road, and spreading to them stories of the battle not going

well for them. The final brigade to arrive at this point in the

afternoon was Colonel Oliver O. Howard's. They had already marched ten

miles or more that day in the heat and gathering dust, all the time

hearing the growing din of battle ahead of them. Then they encountered

the stragglers, and meanwhile Howard had not had the sense to allow the

men to leave behind their heavy field packs. By the time they crossed

Sudley Ford and approached the right of the Yankee battle line, perhaps

a fourth of some of his regiments had dropped out from exhaustion.

At 4 P.M. Howard came on the field and was told to go to the right

flank. He put his brigade in line, dressed the ranks, and ordered the

first line forward. The fire from Elzey's line withered them, and as

they began falling back, Howard sent forward his second line. It, too,

was repulsed, and an alarming number of the men ran for the rear in

panic until they got out of the fire. Meanwhile, over on the Confederate

right, Keyes, too, had been handily repulsed, with the result that both

of the Southern flanks were fairly secure, while the Federal line became

increasingly shaky. More and more of the once distant Confederate

brigades were being forwarded by Johnston. Bonham's regiments now came

into line on the extreme left, and then at the most fortuitous possible

moment, Bonham's men saw yet more troops coming their way from the rear.

Kirby Smith had literally just jumped off the train from the Shenandoah

and was bringing his regiments straight to the most vital part of the

line after a grueling six-mile march from the depot. Along the way Smith

encountered Johnston, whose only order to him was to "go where the fire

is hottest."

|

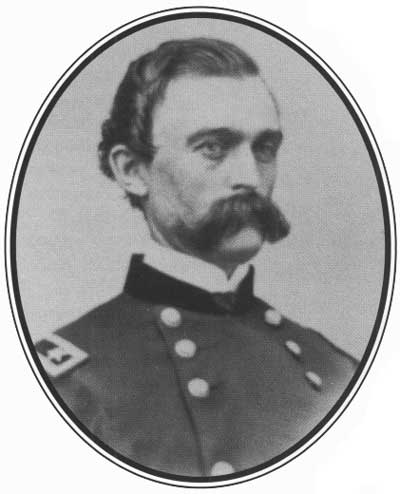

CHARLES GRIFFIN (USAMHI)

|

Smith rushed forward through the stragglers and the wounded and about

4 P.M. took his place in the line, just in time for Smith himself to

fall with a wound before he actually got into the fight. Elzey resumed

command of his brigade then and took it through a wood to emerge with a

wonderful view of Howard's now-exhausted Federals directly before him.

At once he ordered a charge. "Give it to them, boys!" he shouted. The

Rebels rushed forward as the terrified and demoralized Federals withdrew

before them. By the time Elzey finished his charge, Howard and his men

were nowhere to be seen. Beauregard rode up to congratulate Elzey yet

neither appreciated yet just what had happened. Howard's retreat

signaled the beginning of the breakup of McDowell's army.

|

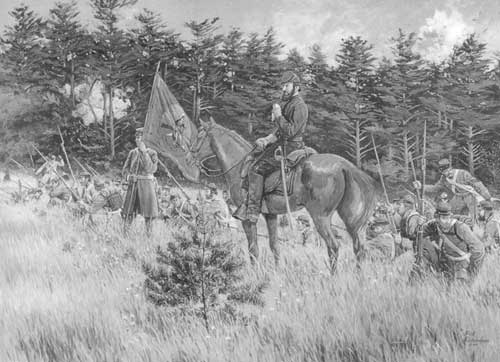

BRIGADIER GENERAL THOMAS J. JACKSON AND HIS BRIGADE ANCHORED THE NEW

CONFEDERATE POSITION ON THE EASTERN EDGE OF HENRY HILL. (PAINTING BY

DICK RICHARDSON)

|

Minutes before Beauregard had been in something of a panic himself.

Off in the distance to his rear around 4 P.M. he spotted through his

binoculars a cloud of dust obviously raised by a column of thousands of

marching soldiers rushing to the front. Coming from the southwest, it

could be more reinforcements sent by Johnston. But it might also be a

new Federal column, perhaps even some of Patterson's army from the

Shenandoah for all he knew. At the moment, barely holding his own

against McDowell, he knew he could not withstand new assaults from a

whole fresh enemy army. Tense minutes followed as Beauregard kept

looking at the cloud, trying to make out flags. When the head of the

group was perhaps a mile distant, he could see a flag, but it draped

limply about its staff, unrecognizable. Then, just as Elzey started his

attack, a blessed gust of wind unfurled the folds of the flag and

Beauregard could see that it was Confederate. It was Jubal Early's

brigade, arriving at precisely the right time and place.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE UNION LINE DISINTEGRATES (4:00-5:00 P.M.)

With the Confederates tightening their grip on Henry Hill, General

McDowell directs Colonel Oliver O. Howard's brigade to Chinn Ridge. As

these Union troops move into position they are confronted by Confederate

reinforcements rushing up from Manassas Junction. These troops, led by

Colonels Joseph Kershaw, Jubal Early, and Arnold Elzey, force the

Federals off Chinn Ridge.

|

Together, Early and Elzey hit the exposed Federal right flank, while

Stuart placed his cavalry on their extreme left and joined in the push.

The Yankees fell back before them almost without resistance, and when

Early crested a small rise he could see thousands of them fleeing in

panic beyond the Warrenton turnpike. "We scared the enemy worse than we

hurt him," Early recalled, but the effect was just as decisive. Howard

himself confessed that "it was evident that a panic had seized all the

troops in sight." Men ran in abject terror yelling, "The enemy is upon

us! We shall all be taken!" Howard and other officers frantically, and

futilely, rode along the lines and among the panicked groups trying to

halt them. It was no use.

|

KURZ AND ALLISON LITHOGRAPH DEPICTING THE BATTLE. (LC)

|

|

ARNOLD ELZEY (LC)

|

Seeing what was happening, Beauregard seized the moment and ordered a

charge by his whole battle line. Badly battered themselves, still the

Confederates found the courage and energy to rush forward, and almost

everywhere the Federals fell back with little resistance. "There were no

fresh forces on the field to support or encourage them," lamented one of

McDowell's staff, "and the men seemed to be seized simultaneously by the

conviction that it was no use to do anything more and they might as

well start home."

Now the impact of all the stragglers began to be felt as their

numbers swelled, first by Howard's panicked men, and then by others from

the rest of the line. Panic infected the whole army.

|

UNION ATTACK ON HENRY HILL. (BL)

|

If McDowell had not recognized that the battle turned against him

sometime earlier when his attacks stalled and the Confederates dug in,

he surely could see it now. His last hope had been an order for Tyler to

move across a fresh brigade on the Confederate right. If he could get

Keyes's regiments, followed by Schenck's around between Bull Run and

Henry Hill, he might retrieve the situation by doing to Beauregard what

the arrival of Elzey and Early had done to him. But before the movement

was fairly under way a message came to Tyler that "the army is in full

retreat towards Bull Run." Refusing at first to credit the report, Tyler

soon saw for himself that it was true. Immediately Keyes was ordered to

pull back. Now he would have to help cover the retreat of the army.

"As we emerged from the woods one glance told the tale; a tale of

defeat, and a confused, disorderly and disgraceful retreat," groaned one

of Keyes's infantrymen. "The road was filled with wagons, artillery,

retreating cavalry and infantry in one confused mass, each seemingly

bent on looking out for number one and letting the rest do the same." No

remnant of regimental or brigade organization prevailed. The army had

become a mob, deaf to orders or duty, intent on escape. "The plain was

covered with the retreating troops," McDowell would report, "and they

seemed to infect those with whom they came in contact. The retreat soon

became a rout, and this soon degenerated still further into a

panic."

|

IN THE EIGHT MONTHS THAT FOLLOWED THE BATTLE, OCCUPYING CONFEDERATE

TROOPS DISMANTLED THE HENRY HOUSE AS THEY SEARCHED FOR FIREWOOD,

BUILDING MATERIAL, AND BATTLEFIELD MEMENTOS. (LC)

|

Seeing what was happening before them, Beauregard and Johnston now

started to order their forces forward, starting with those on the left

of their line, racing after the fleeing Yankees. While Early chased

Howard, Stuart's cavalry captured so many prisoners on the road back

toward Sudley Ford that he had to stop, unable to move with all of the

surrendered foemen on his hands.

Confederates in the center of the line started for the stone bridge,

hoping to cross it and cut off the retreat of McDowell's men who were

escaping via the roundabout Sudley Ford route. Johnston sought any

remaining reserves to push them forward, ordering Beauregard to press

the pursuit. If they could get to Centreville before the Yankees did,

they would have McDowell cut off from Washington and with little option

but to fight with a shattered army, or else disperse or surrender.

Fortunately for McDowell, one of his fresh brigades that never got

into the fight was able to hold the road to Centreville, and then when a

rumor of a Federal attack impending on the far right down near the

Orange & Alexandria bridge came in, most of the pursuit was called

off. The report proved to be erroneous, but it helped to save the Union

army. The only remaining Confederates really pressing the chase were

some Virginia cavalry, and they nearly caught up with the enemy to make

one last assault.

|

|