|

|

"MY VERY DEAR WIFE"

Sullivan Ballou was a successful, 32-year old attorney in Providence,

Rhode Island, when Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers in the wake of

Fort Sumter. Responding to his nation's call, the former Speaker of the

Rhode Island House of Representatives enlisted in the Second Rhode

Island Infantry, where he was elected major. By mid-July, the swirling

events in the summer of 1861 had brought Ballou and his unit to a camp

of instruction in the Federal capital. With the movement of the Federal

forces into Virginia imminent, Sullivan Ballou penned this letter to his

wife. His concern that he "should fall on the battle-field" proved all

too true. One week after composing his missive, as the war's first major

battle began in earnest on the plains of Manassas, Ballou was struck and

killed as the Rhode Islanders advanced from Matthews Hill.

Regrettably, the story of Sullivan Ballou does not end with a hero's

death on the field of battle and a piercing letter to a young widow.

During the weeks and months that followed the battle, Confederate

forces occupying the area of the battlefield desecrated the graves of

many fallen Federals. As a means of extracting a revenge of sorts

against the Union regiment at whose hand they had suffered, a Georgia

regiment sought retribution against the Second Rhode Island.

Supposing they had disinterred the body of Colonel John Slocum,

commanding the Rhode Islanders during the battle, the Confederates

desecrated the body and dumped it in a ravine in the vicinity of the

Sudley Methodist Church. Immediately following the Confederate

evacuation from the Manassas area in March 1862, a contingent of Rhode

Island officials, including Governor William Sprague,

visited the Bull Run battlefield to exhume their fallen sons

and return them to their native soil. Led to the defiled body, the party

examined the remains and a tattered remnant of uniform insignia and

discovered that the Confederates had mistakenly uncovered the body of

Major Sullivan Ballou, not his commanding officer. The remains of his

body were transported back to Rhode Island, where they were laid to

rest in Providence's Swan Point Cemetery

Of the tens of thousands of letters written in the days leading up to

the First Battle of Manassas, certainly none is more famous than the

last letter of Major Sullivan Ballou. As poignant as it is prescient,

Ballou's epistle captures not only the spirit of patriotic

righteousness that led many men to the enlistment office, but it also drives

home the stark reality that casualties of war were not confined to the

battlefield. There were hundreds of thousands of soldiers who would

not return to their families over the next four years, leaving behind

a Sarah, or a Willie and Edgar who would "never know a father's love and

care." Very few, however, had the foresight or the eloquence to leave

behind a legacy as touching as Sullivan Ballou's to his grief-stricken

family.

Headquarters, Camp Clark

Washington, D.C., July 14, 1861

My Very Dear Wife:

Indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days, perhaps

to-morrow. Lest I should not be able to write you again, I feel

impelled to write a few lines, that may fall under your eye when I shall

be no more.

Our movement may be one of a few days duration and full of pleasure

and it may be one of severe conflict and death to me. Not my will, but

thine, O God be done. If it is necessary that I should fall on the

battle-field for any country, I am ready. I have no misgivings about, or

lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage

does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American civilization now

leans upon the triumph of government, and how great a debt we owe to

those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the

Revolution, and I am willing, perfectly willing to lay down all my joys

in this life to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt.

But, my dear wife, when I know, that with my own joys, I lay down

nearly all of yours, and replace them in this life with care and

sorrows, when, after having eaten for long years the bitter fruit of

orphanage myself, I must offer it, as their only sustenance, to my dear

little children, is it weak or dishonorable, while the banner of my

purpose floats calmly and proudly in the breeze, that my unbounded love

for you, my darling wife and children, should struggle in fierce, though

useless, contest with my love of country.

I cannot describe to you my feelings on this calm summer night, when

two thousand men are sleeping around me, many of them enjoying the last,

perhaps, before that of death, and I, suspicious that Death is creeping

behind me with his fatal dart, am communing with God, my country and

thee.

I have sought most closely and diligently, and often in my breast,

for a wrong motive in this hazarding the happiness of those I loved, and

I could not find one. A pure love of my country, and of the principles I

have often advocated before the people, and "the name of honor, that I

love more than I fear death," have called upon me, and I have

obeyed.

Sarah, my love for you is deathless. It seems to bind me with mighty

cables, that nothing but Omnipotence can break; and yet, my love of

country comes over me like a strong wind, and bears me irresistably on

with all those chains, to the battlefield. The memories of all the

blissful moments I have spent with you come crowding over me, and I feel

most deeply grateful to God and you, that I have enjoyed them so long.

And how hard it is for me to give them up, and burn to ashes the hopes

of future years, when, God willing, we might still have lived and loved

together, and seen our boys grow up to honorable manhood around us.

Something whispers to me, perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my

little Edgar, that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do

not, my dear Sarah, never forget how much I love you, nor that, when my

last breath escapes me on the battle-field, it will whisper your

name.

|

I know I have but few claims upon Divine Providence, but something

whispers to me, perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar, that

I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not, my dear Sarah,

never forget how much I love you, nor that, when my last breath escapes

me on the battle-field, it will whisper your name.

Forgive my many faults, and the many pains I have caused you. How

thoughtless, how foolish I have oftentimes been! How gladly would I wash

out with my tears, every little spot upon your happiness, and struggle

with all the misfortune of this world, to shield you and my children

from harm. But I cannot, I must watch you from the spirit land and

hover near you, while you buffet the storms with your precious little

freight, and wait with sad patience till we meet to part no more.

But, O Sarah, if the dead can come back to this earth, and flit

unseen around those they loved, I shall always be near you in the garish

day, and the darkest night amidst your happiest scenes and gloomiest

hours always, always, and, if the soft breeze fans your cheek, it shall

be my breath; or the cool air cools your throbbing temples, it shall be

my spirit passing by.

Sarah, do not mourn me dear; think I am gone, and wait for me, for we

shall meet again.

As for my little boys, they will grow as I have done, and never know

a father's love and care. Little Willie is too young to remember me

long, and my blue-eyed Edgar will keep my frolics with him among the

dimmest memories of his childhood. Sarah, I have unlimited confidence in

your maternal care, and your development of their characters. Tell my

two mothers, I call God's blessing upon them. O Sarah, I wait for you

there! Come to me, and lead thither my children.

—Sullivan

|

SULLIVAN BALLOU (ENGRAVING BY J.A. O'NEILL COURTESY RHODE ISLAND

HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

It had not been much of a "battle," little more than a skirmish by

later standards but it put resolve and courage into the Confederates who

had stood their ground. Richardson's 3,000 were repulsed by the 5,000 or

more under the combined command of Longstreet and Early, and from that

the entire Confederate line took heart. Indeed, some thought this was

the battle, and the war was over, the Yankees repulsed. Beauregard knew

better, of course, but he could also be thankful that McDowell's advance

had been held up a day. It was a day that could prove crucial, for with

the whole Union army on the verge of wetting its feet in the waters of

Bull Run, he needed to buy time in the hope that Johnston could come

from the Shenandoah.

Would Johnston come? There had been anxious days in the Shenandoah

while events unfolded east of the Blue Ridge. General Patterson proved

to be a slow, doddering, hesitant commander, who took his time about

advancing on Harpers Ferry. But eventually he did get across the

Potomac, while an understrength Johnston had no choice but to fall back

before him. Able skirmishing and Patterson's temerity, however, worked

to slow his advance thereafter, so that by the second week of July

Johnston's Confederates were firmly planted at Winchester, twenty miles

south of the Potomac, with the vital Manassas Gap rail line still in

their control and no sign of Patterson advancing further.

|

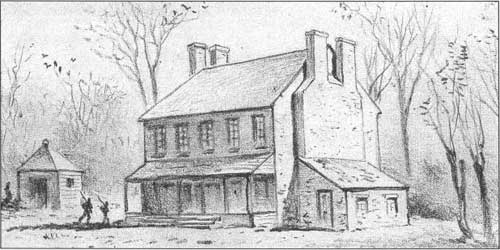

THE LEWIS HOUSE SERVED AS JOHNSTON'S HEADQUARTERS DURING THE BATTLE.

(LC)

|

Not until July 16 did the Yankees show signs of making a tentative

advance again. Patterson knew that McDowell was starting his march that

day, and somehow he reasoned that by making a faint-hearted show of

force in front of Winchester, he could keep Johnston pinned down and

unable to reinforce Beauregard. But the whole thing backfired. Timid to

the point of foolishness, Patterson's small demonstration against

Winchester only left him convinced that he could not move further and

that Johnston had 42,000 in his army instead of the 12,000 or more

actually there. By magnifying enemy numbers almost three times in his

imagination, Patterson defeated himself. As he and his staff officers

slapped each others' backs and congratulated themselves that they had

pinned down Johnston in spite of his superior numbers and that McDowell

would now win a great victory thanks to them, they sat down intending to

do nothing more during the campaign.

But then came an angry order from Scott that they were not to let

Johnston fool them. They must attack him and keep attacking. On the

morning of July 18, having already withdrawn from the Winchester area,

Patterson put his army back on the road. "The enemy has stolen no march

on me," he confidently wired to Washington. But then some of his

volunteer regiments refused to go on, their 90-day enlistments having

expired. Glad to have an excuse not to do anything, Patterson decided

that he could not advance with a reduced and balky army. But he did not

need to advance anyhow, he reasoned. "I have succeeded," he wired to

Scott, "in keeping General Johnston's force at Winchester."

At that very moment, Johnston's Confederates were already on their

way to Manassas. The Army of the Shenandoah had lived under constant

threat of enemy advance for days, but as time wore on Johnston became

increasingly convinced that Patterson did not have the stomach for a

fight. When he found out that Patterson had actually moved his army

seven miles away from Winchester after the halfhearted demonstration of

July 16, Johnston realized that he would be able to get all or part of

his command away if needed. On the seventeenth came a telegram from

Beauregard announcing that Richmond had ordered Johnston to move to

Manassas immediately. "Do so, if possible," said Beauregard, "and we

will crush the enemy." Confirmation arrived early the next morning from

Richmond itself. No one knew whether McDowell might attack the next day.

If he did, Johnston could not possibly be there. If he did not, then

still there might be time.

|

JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON (LC)

|

|

CONFEDERATE TROOPS ABOUT TO DEPART FOR MANASSAS. (BL)

|

Early on July 18 reveille sounded in Johnston's camps. No one told

the men where they were going, but hastily they packed their equipment,

and then Jackson's Virginia brigade marched off southeastward toward

Piedmont Station, the nearest point on the Manassas Gap line, "We are

all completely at a loss to comprehend the meaning of our retrograde

movement," one of his men complained to his diary. They would know soon

enough. Jackson pushed them fast and then informed them of their

destination. That put heart into the men and they marched with renewed

vigor, knowing that every minute saved could be Confederate lives at

Manassas. Not until 2 A.M., July 19. did they halt for the night at

Paris.

Behind them came the other brigades, one by one, first Bee, then

Bartow, and finally Kirby Smith, temporarily commanding Elzey's brigade

since his own was not completely organized. Johnston himself rode ahead

of the army toward Piedmont Station to arrange the trains to transport

his men. When he arrived he met a messenger with word of the fight

earlier that day at Blackburn's Ford. Now real urgency drove the

Southerners. Sending back word to Beauregard that he was coming and that

parts of his command would arrive on the morrow, Johnston worked

throughout the night. When Jackson's column marched into sight around 6

A.M., July 19, some cars awaited them, and within a few hours

the entire brigade was on its way eastward.

Exhausted after marching and riding sixty miles in the past

twenty-eight hours, the Virginians collapsed on the ground, unaware as

yet tat they had just made history . . .

|

It was a hair-raising trip for some, many of the boys being on a

train for the first time in their lives, While the officers grumbled at

the slow pace of the engine, the men marveled at the speed of their

progress. At every town and hamlet along the way, townspeople turned out

to cheer them on while the women waved their handkerchiefs, It took them eight

hours, but finally they saw smoke in the distance that signaled their

approach to Manassas Junction. It rose above Beauregard's campfires.

They had come in time. Exhausted after marching and riding sixty miles

in the past twenty-eight hours, the Virginians collapsed on the ground,

unaware as yet that they had just made history, being the first soldiers

ever to make a major territorial shift by rail from one war zone to

another.

Behind them came the others. There was only one engine on the

Manassas Gap line, so Bartow had to wait for the train to return to

Piedmont Station before he could embark his brigade. They would travel

all night, not reaching Manassas until daylight July 20. At that same

time Bee boarded his brigade, thanks to Johnston finding another train

somewhere, and this engine moved at seeming light speed, getting Bee's

brigade to Manassas shortly after noon that same day. That still left

some elements of Bee's, Bartow's, and all of Elzey's

brigade—commanded by Smith—awaiting transportation, with

Smith's own command hurrying on as well. It was 3 A.M., July 21, when

the next train left, carrying most of Elzey's brigade, and behind them

would come one last train bringing some of the remnants. They could not

arrive before dawn, July 21, at the earliest. Meanwhile, Johnston's

cavalry, commanded by Colonel James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart rode hard

for thirty-six hours and reached Manassas late July 20.

|

WILLIAM T. SHERMAN (LC)

|

Jefferson Davis, Beauregard, and Johnston had achieved a small

miracle. In barely forty-eight hours they put together a concentration

that came close to doubling the strength of the army along Bull Run,

doing it virtually under the guns of the enemy, completely fooling

Patterson in the Shenandoah, and even deceiving McDowell as to the

meaning of the sound of the train whistles coming into and going out of

Manassas Junction. Davis rushed other isolated units to the front from

elsewhere in Virginia, too. For the first time in history, railroads

served decisively in warfare. Now their combined 34,000 troops were

almost the equal of McDowell's 35,000, testimony to the foresight of

Robert E. Lee and General Cocke, who originally conceived the

scheme.

Now it was up to Johnston and Beauregard to capitalize on their good

fortune and planning. Johnston's commission made him senior, and he

immediately assumed overall command. However, Beauregard had been on

this ground for weeks, knew the defenses and the troops there emplaced,

and he had the best knowledge of what McDowell had done to date.

Moreover, Beauregard had a plan. A would-be Napoleon, the Louisianian

always had a grand scheme, and now he assumed that Johnston would go

along with his plan to attack McDowell. Simply put, Beauregard meant to

push most of his brigades across Bull Run early on July 21, with most of

his strength—including Johnston's troops—on his right flank.

They would push around the Federal left flank and cut off McDowell from

his line of retreat via Fairfax Court House. That done, they could

disperse or destroy the Yankee army while leaving it nowhere to run.

Johnston readily agreed, perhaps not realizing that in so doing he was

yielding much of his ability to influence the ensuing battle to his

subordinate.

|

JAMES EWELL BROWN (J.E.B.) STUART (LC)

|

|

THE STONE BRIDGE AS IT APPEARS TODAY. (NPS)

|

It was not a good plan. It put two-thirds of their army on the right

side of their eight-mile-long line, leaving the left very thinly

defended, and Sudley Ford entirely uncovered. One and one-half brigades

were left to cover three miles all by themselves, including the best

fords and the stone bridge, along a stretch where Bull Run was shallow

enough to wade across in places not usually fordable.

But Tyler's demonstration at Blackburn's Ford had convinced

Beauregard that McDowell intended his main attack there or at nearby

Mitchell's Ford in the center of the Confederate line, and once

believing that he knew what an opponent thought, Beauregard could not or

would not change his mind. Should McDowell strike the weaker side of his

line before Beauregard got his own plan into motion, all the fruits of

Johnston's arrival might be lost.

Worse, Beauregard bungled the written orders instructing the several

brigades as to their positions and movements. They were far too complex,

and in one case the wording was so ambiguous that, read literally, it

ordered one brigade to attack another Confederate brigade!

Nevertheless, when Beauregard gave Johnston a copy of the order to sign

at 4:30 A.M., July 21, the Virginian did not question it, another case

of abrogating his responsibility to his subordinate. They were committed

now. All they and their soldiers could do was try to get a little more

sleep before the opening of the battle to save Virginia and the

Confederacy.

|

|