|

The Confederates had built signal stations on high elevations, and

from one of them signalmen spotted the Yankee advance and used their

wig-wag flags to send Evans news of the move toward Sudley Ford. He

realized at once that the enemy intended to attack the left flank of the

Confederate army, namely his own tiny command. He sent word to

headquarters at once and then took action on his own. The Yankees had to

be stopped or delayed long enough for Beauregard to send reinforcements.

Faced with three full brigades in his front and two divisions coming at

him off to the left, Evans had but one thought. Outnumbered around

twenty-to-one, he decided to attack.

|

A LOUISIANA TIGER (BL)

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

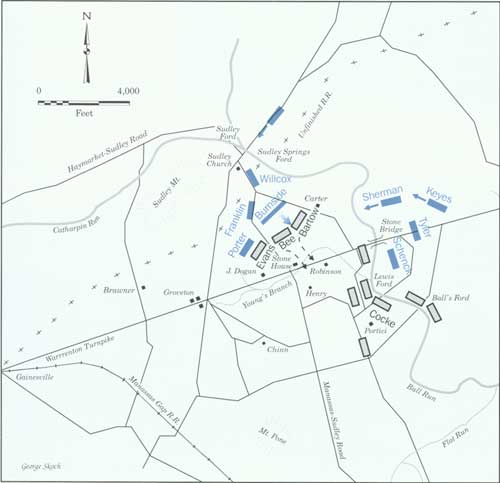

THE FIGHT FOR MATTHEWS HILL (10:00-11:30 A.M.)

Colonel Evans arrives on Matthews Hill shortly before Colonel Ambrose

Burnside's brigade. After thirty minutes of fighting Evans's brigade

gives ground grudgingly. Reinforcements under the command of General

Barnard Bee and Colonel Francis Bartow rush to Evans's assistance. As

the two lines exchange volleys of musketry, two more Union brigades

under Colonels William Sherman and Erasmus Keyes cross Bull Run and

threaten to cut off the Confederate left from the rest of the army. The

Confederate line disintegrates and the men begin streaming toward the

rear.

|

The combative Confederate left a mere 300 men at the bridge to

skirmish with Tyler's division and moved the balance northwest to a

ridge called Matthews Hill. There he took cover in a line of trees, and

around 10:15 when the head of Burnside's column came into sight across a

field Evans opened fire. It took Hunter's column by surprise, and for

the next several minutes the Yankees were in some confusion before they

established a battle line. Then, incredibly, Evans charged right into

the center of the Union line. Leading the attack were the colorful

Louisianians of the First Battalion, dressed in their baggy striped

zouave pants, with bowie knives in their hands. The attack could hardly

turn back Hunter, but it did delay him, and that was all Evans hoped

for. Around 11 o'clock the first reinforcements, portions of Bee's

brigade, arrived on the field to strengthen Evans's paper-thin line, and

soon thereafter Bartow arrived with two Georgia regiments. Now the

Confederates totaled about 2,800 men, still a fraction of what the

Yankees had, but enough to mount a spirited defense.

|

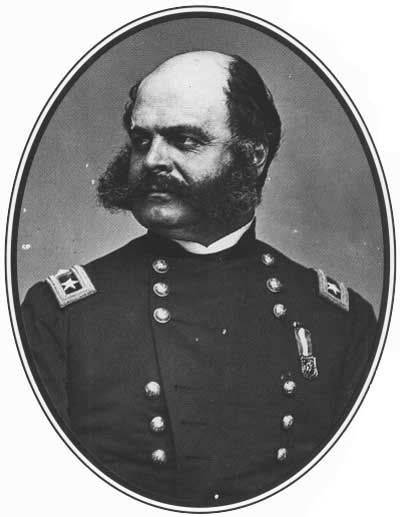

AMBROSE E. BURNSIDE (LC)

|

Again Evans readied an attack, then the small Confederate line swept

up the southeast slope of Matthews Hill. This time they raced into an

inferno. In fifteen minutes the Eighth Georgia was cut to pieces.

Bartow's horse was shot from under him. The Fourth Alabama advanced

alone after all the other Confederate regiments were halted in the rain

of lead and found itself facing much of Hunter's line alone. "Our brave

men fell in great numbers," a captain said days later. Soon they found

the enemy advancing and faced Yankees in front and on both sides. They

were almost surrounded and had to retreat under a galling fire. The

Federals had the momentum. Evans would launch no more attacks. But he

had bought time. Now he would start to pay for it with lives as the

enemy came on.

|

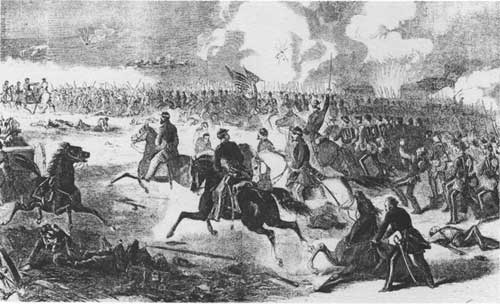

COLONEL AMBROSE BURNSIDE (ASTRIDE THE REARING HORSE) URGED HIS MEN

FORWARD IN THE FIGHT FOR MATTHEWS HILL. (LC)

|

|

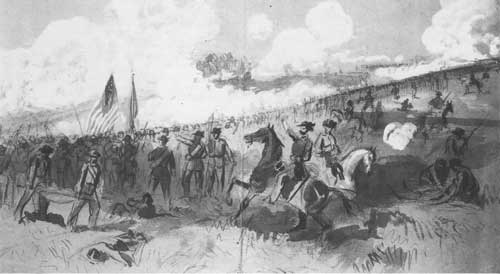

THE TIMELY ARRIVAL OF BRIGADIER GENERAL BARNARD E. BEE'S BRIGADE

MOMENTARILY CHEERED THE FEDERAL ADVANCE AT MATTHEWS HILL. (PAINTING BY

DON TROIANI, PHOTO COURTESY OF HISTORICAL ART PRINTS. SOUTHBURY, CT)

|

The Confederates pulled back off Matthews Hill and across a stream

called Young's Branch as they saw the first elements of Heintzelman's

division start to come into line with Hunter. Worse, to their right they

could see that Sherman had finally tired of waiting on the north bank of

Bull Run and had crossed his men in a shallows upstream of the stone

bridge. There was no choice but to pull back what little of Evans's

command was posted by the bridge and consolidate all of the remaining

Southerners on this part of the field. By now some of the regiments were

in tatters. The Fourth Alabama had lost every one of its field officers,

and the remnants were scurrying stubbornly up the slopes of Henry Hill

just south of Young's Branch. Some distance behind his advancing line,

McDowell saw the battle going his way despite the delays and setbacks of

the morning, and took off his hat and rode along his lines shouting

"Victory! Victory! The day is ours."

Perhaps not just yet, for Evans, Bee, and Bartow were not done

resisting the Yankee push. Moreover, though taken by surprise,

Beauregard and Johnston were reacting well. Thanks to Evans in

particular, their battered left flank had held beyond all expectation.

Now all across the ground below Bull Run brigade after brigade was on

the march to the left, all intent on converging on Henry Hill. At that

very moment the train bearing Kirby Smith's brigade was nearing the

junction, and those men could be on the battle line in a few hours if

the Confederates held out. The battle was out of Beauregard and

Johnston's control, to be sure, but they were still in the fight. They

both rode to the front to direct the placement of reinforcements as they

arrived, and then while Beauregard remained there, Johnston went behind

the lines to hurry forward each brigade as it came available. And up on

Henry Hill itself, even as the battered defenders prepared to receive

what looked like the strongest Yankee thrust yet, some looked to the

rear and saw the approach of a fresh brigade. Thomas J. Jackson was on

the way.

McDowell's "victory" was not won yet, not so long as those Rebels

stayed put on Henry Hill, and now he concentrated on driving them from

it. Shortly after 1:30 his line was stable enough to start the push

across Young's Branch. Sherman and Porter formed the line. With them

were two batteries of artillery commanded by Charles Griffin and J. B.

Ricketts. Hunter had been wounded early and was out of action, but

Heintzelman's division was arriving and starting to go into position on

the right of Hunter's line, now commanded by Porter. At last the

numerical advantage on this part of the field was starting to become

manifest. Surely the Rebels could not resist a concerted onslaught by

this gathering host.

|

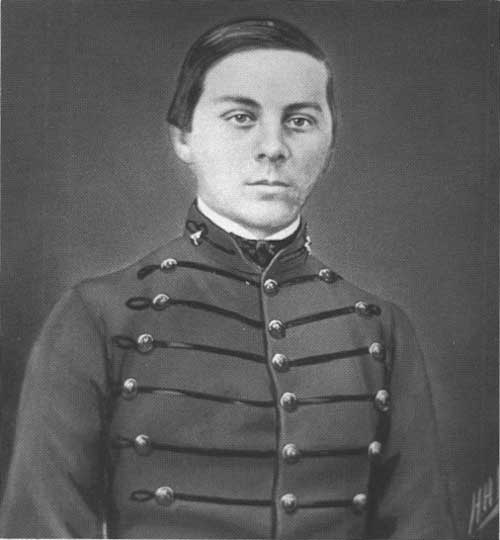

THE DEATH OF A YOUNG CADET

Charles R. Norris was a 17-year-old cadet at the Virginia Military

Institute when the war opened in April 1861. While the older cadets were

ordered out to Richmond to assist in training incoming volunteers Norris

and some of his classmates remained in Lexington to guard the Institute

and help train locally organized troops. Duty and the prospect for

future service prevented the cadet from chafing at his assignment to a

somewhat isolated post. Writing to his family in Leesburg, Virginia, he

declared, "You need not send for me or want me to come home for I would

not leave for a thousand dollars."

On April 22 Norris joined nine of his fellow cadets on a detail to

accompany a shipment of ammunition to Harpers Ferry, where the men

reported to Thomas J. Jackson, then in command of the post. Jackson,

himself a former V.M.I. professor, valued the discipline and experience

of the cadets and kept them on hand to drill the inexperienced soldiers

of his newly formed brigade. Norris remained with Jackson's command

through the early summer and was present when orders arrived to transfer

the brigade to Manassas Junction. An officer's absence provided the

cadet with an opportunity for greater service, and Norris assumed the

role of acting captain of a company in the 27th Virginia Infantry.

|

CHARLES R. NORRIS (COURTESY OF CHARLES R. NORRIS, 3RD AND FAMILY)

|

When Jackson's Virginia brigade arrived on Henry Hill

during the battle on July 21, the 27th Virginia took up position near

the center of the Confederate line. As the battle reached its climax,

the Virginians braved a storm of iron from Union artillery on the far

side of the bill. When Jackson unleashed his troops on a charge to

capture the enemy guns, Norris cried out to his men, "Come on boys,

quick, and we can whip them!" While leading his company out onto the

field, the boy captain was struck by a bullet or shell fragment and fell

dead. The next day his older brother, Joseph, located Charles's body and

carried the remains home for burial in Leesburg.

At his death on the battlefield, Charles Norris was wearing a V.M.I.

cadet dress coatee. Proud of his school, he had traded garments with

fellow student Charles Copeland Wight and chose to wear his new coat

into battle. The coat he wore, long treasured by the Norris family,

still bears evidence of his fatal wound and serves as a poignant

reminder of one family's loss.

|

|

HARPER'S WEEKLY ILLUSTRATION COLONEL HUNTER'S ATTACK AT THE

BATTLE OF BULL'S RUN.

|

On the far side of Henry Hill, the remnants of Evans's and Bee's and

Bartow's commands took refuge. However, they had bought time for

reinforcements to arrive, and now fresh troops started coming. First

came Colonel Wade Hampton and the infantry of his South Carolina

legion—a unit with infantry, cavalry, and artillery all in one. He

went into line on the right of the Confederate front, his men still

panting from having just arrived on a train from Richmond and then run

to the front, and from the Warrenton pike to cover the withdrawal of the

Confederates across Young's Branch.

Then came Jackson. He had his men up at 4 A.M. that morning,

expecting to go reinforce Longstreet at Blackburn's Ford. But then later

in the morning he heard the firing off to his left at the stone bridge.

Like Bee and Bartow before him, he did not wait for orders, but assuming

the battle to be there, he instantly put his brigade in motion. By

about 11:30 he approached the scene of action and moved up the back

slope of Henry Hill. Once on the crest, he put his five Virginia

regiments in line just behind the summit, informed Bee of his arrival,

and told his men to lie down and await either the attack of the enemy or

instructions from Johnston.

Here a legend was born. Bee rode to Jackson when he heard of his

arrival.

"General," he cried, "they are beating us back."

"Sir, we'll give them the bayonet," Jackson calmly replied.

Bee seems to have regarded the bayonet comment as an

order—though he and Jackson held equal rank and seniority—and

so he rode back to his command. The confusion was pervasive. A mere

captain commanded the Fourth Alabama now, yet no one could find him at

the moment. Disoriented, Bee did not even recognize some of his own men

at first. Told at last who they were, he shouted, "This is all of my

brigade that I can find—will you follow me back to where the firing

is going on?" They said they would, and he led them back into the

inferno. But before doing so, he almost certainly said something else,

but none present ever agreed on precisely what it was. A few days later

a newspaper man said he was told that Bee cried out, "There is Jackson

standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will

conquer." A few days more, and people in Richmond spoke of Jackson's men

being so staunch under fire that "they are called a stone wall."

Thus was born "Stonewall" Jackson. Yet no one knows for certain what

Bee said, or what he meant exactly. The remark seems like

testimony to Jackson's firmness under fire, yet at the time Bee said it,

Jackson had not yet become engaged and had his men lying down behind the

crest. Others thought it might not be a compliment at all, but rather a

snide comment to the effect that while Bee's men were being mauled,

Jackson kept his command out of the fight, immovable like a stone wall.

Whatever the case, Jackson would be "Stonewall" for the rest of

time.

|

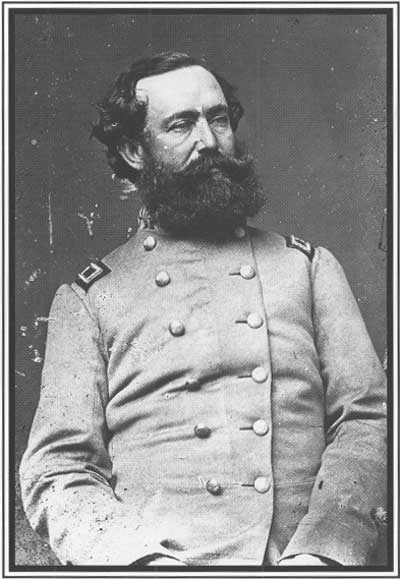

WADE HAMPTON (VM)

|

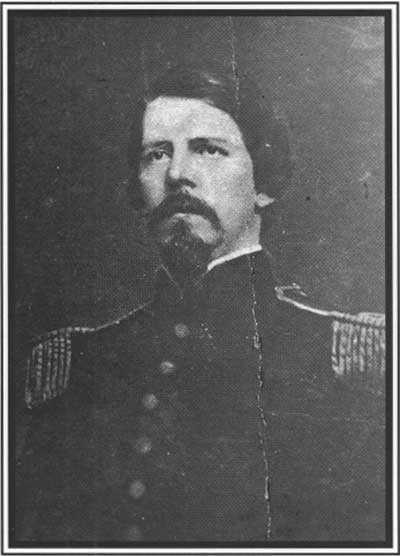

|

BARNARD E. BEE (VM)

|

Bee later rallied his men and led them in a bayonet charge toward

Griffin's and Ricketts's batteries. They came under a terrible fire, and

then Bee plunged from his horse, mortally wounded. Only minutes later,

on another part of the field, Bartow fell with a bullet in his breast.

"They have killed me, boys," he cried. In minutes he was dead.

|

|