|

|

"THE HORRORS AROUND ME"

In 1820, upon a commanding ridge overlooking Bull Run creek, Spencer

Ball built the plantation known as Portici. In July 1861, Portici was

the home of Frank and Fannie Lewis. On the eighteenth life as the

Lewises knew it came to an abrupt halt. Confederate officials notified

the family that a battle was imminent and that their house would most

likely be exposed to the fighting.

On July 21, the horrors of the battle quickly found their way into

Portici. Portici's kitchen and hallways became operating rooms. The

wounded, dead, and dying littered the floors throughout the house.

Medical supplies and skilled personnel were scarce. Throughout the night

of the twenty-first, the work of the surgeon's saw transformed Portici

from a stately manor into a charnel house. John Opie of the Fifth

Virginia Infantry described the scene as he approached one of the field

hospitals, possibly Portici: "There were piles of legs, feet, hands and

arms, all thrown together, and at a distance, resembled piles of corn at

a corn-shucking."

|

JAMES B. AND FANNY RICKETTS (LC)

|

Among the wounded soldiers taken to Portici was Federal artillery

Captain James B. Ricketts. Ricketts received a wound to the thigh during

the fighting on Henry Hill. The wife of Captain Ricketts, Frances

"Fanny" Ricketts, was living in Washington, D.C., when she learned of

the Union defeat at Bull Run. Conflicting reports from the battlefield

cast doubt over the fate of her husband. Unable to gain adequate

information on her husband's wounds, Fanny set out for Manassas on the

twenty-fifth. She arrived at Confederate headquarters that evening.

There she received the news that her husband was alive and being cared

for at the Lewis house.

Early the next morning she arrived at Portici. Quickly the reality of

war became evident to Fanny. She vividly described the horrors at

Portici in a journal. She wrote, "Oh nothing, no words can describe the

horrors around me, two men dead and covered with blood are carried down

the stairs as I waited to let them pass. On the table in the open hall a

man was undergoing amputation of the leg, at the foot of the stairs two

bloody legs lay and through it all I went to my husband."

Fanny spent a week at Portici tending to the needs of her husband and

other wounded soldiers. She wrote, "In the opposite room are ten dying

or wounded men. Next to us are three, one with a gangrenous thigh where

it is amputated. The smell is horrible. No one can dream of the

sickening horrors of this place." Finally on August 2, 1861, Captain

Ricketts was transferred to Richmond, Virginia. Fanny accompanied her

husband and remained with him until his release in December.

After the war moved away from Manassas, Portici remained abandoned.

The house occasionally served as temporary quarters for troops moving

through the area. Sometime in late 1862, a fire devastated Portici

leaving only the memories of the horror witnessed within its walls.

|

THE LEWIS HOUSE, PORTICI. (USAMHI)

|

|

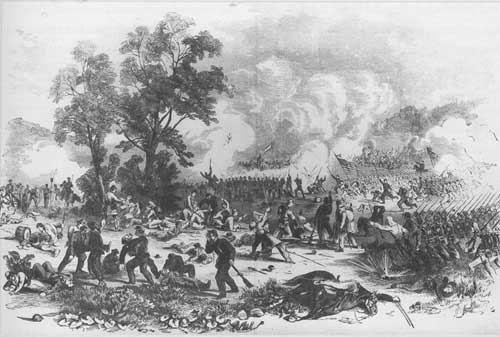

As badly as the battle went for McDowell, the withdrawal went

infinitely worse, a shambles from start to finish. Some of his men got

back across Bull Run at the stone bridge and had a good road ahead of

them for Centreville. But much of the line had to go all the way back to

Sudley Ford and then somehow thrash overland or take the circuitous

paths to get them back to the Warrenton Turnpike. And once on the main

road, the whole army had to use a single narrow bridge to get over

another stream called Cub Run. Men could wade or swim, but its banks

were too steep for wagons and artillery. Everything must cross that one

bridge. Thus when a small body of pursuing Confederates halted on a hill

overlooking the run and managed to place an artillery shell right in the

center of the bridge, a team on the span panicked and turned over its

wagon, effectively blocking the way for any further traffic. It happened

just as the two main bodies of fleeing Yankees approached, and the

effect of seeing their path of retreat this blocked put the finishing

touches on the panic.

|

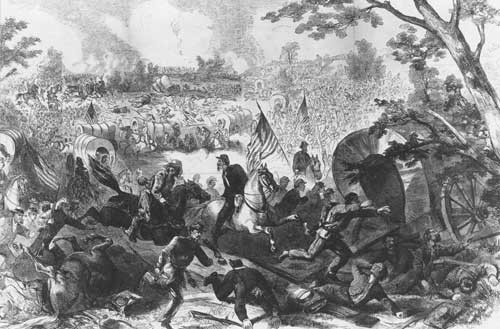

AS RUMORS THAT THE FEARED CONFEDERATE BLACK HORSE CAVALRY WAS SWEEPING

DOWN ON THE RETREATING FEDERALS, THE UNION ARMY DEGENERATED INTO A

PANIC-STRICKEN MOB FLEEING PELL MELL FOR THE SAFETY OF WASHINGTON. (LC)

|

|

THE STONE BRIDGE WAS DESTROYED BY CONFEDERATE FORCES

AS THEY EVACUATED THE AREA IN MARCH 1862. (LC)

|

"Then a scene of confusion ensued which beggars description," said

Keyes. "Cavalry horses without riders, artillery horses disengaged from

the guns with traces flying, wrecked baggage-wagons, and pieces of

artillery drawn by six horses without drivers, flying at their utmost

speed and whacking against other vehicles." Men everywhere threw down

their packs, their guns, even their hats and canteens, in the mad rush

to disencumber themselves of anything that might delay their flight.

"The rush produced a noise like a hurricane at sea." About now the body

of pursuing Virginians launched their attack, and though enough Federals

rallied to repulse them, the impression of Confederates hard at their

heels finished off the last of the resolve of McDowell's army. They were

battered, demoralized, and utterly defeated.

|

RUINS OF THE BRIDGE AT CUB RUN MARCH 1862. (LC)

|

By now it was about 7 P.M. and Beauregard recalled his scattered

units. It would be dark soon, and his own army was nearly as

disorganized as the enemy's by the grueling and confused fighting and

marching of the day. Already his men were looting the knapsacks and

other abandoned baggage of the Federals or bringing in triumphantly the

captured horses, wagons, and guns. McDowell himself came close to being

one of the prizes brought Back. He was among the last to cross Cub Run.

Though shaken—indeed, shocked—by the rout of his army and

dazed at how his "victory" of that morning had so suddenly become a

disaster, he bravely tried to rally those he could to erect a rearguard.

He already had a reserve division at Centreville commanded by Dixon

Miles—who unfortunately spent the day getting drunk—and by

combining these forces he at last felt some degree of security against

an enemy attack for that night at least. The next day he would start the

remnant of his army on the way back to Washington, where thousands of

his men were fleeing even now without awaiting orders to do so.

|

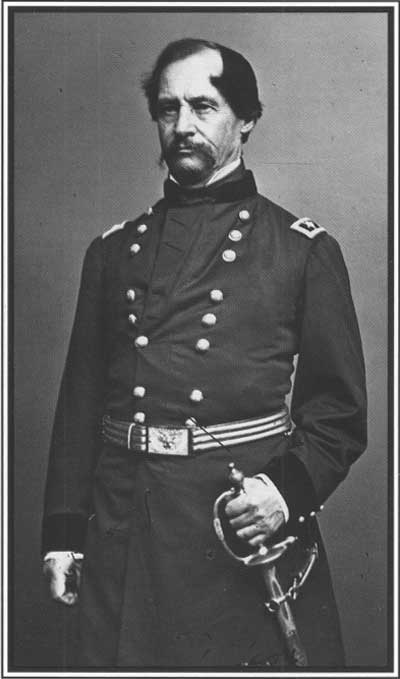

FRANCIS S. BARTOW (BL)

|

|

DAVID HUNTER (LC)

|

With the sounds of skirmishing still echoing over the battlefield,

President Jefferson Davis himself arrived on the ground, having taken a

train from Richmond. He first met Johnston, who informed him of the

victory, and then together they rode out over the field cheering the

troops and looking for Beauregard. Later that evening the president

pressed his two generals to launch a vigorous pursuit, but they were

reluctant, knowing themselves to be almost as battered as the enemy.

Even a beaten foe could turn dangerous if McDowell somehow stopped the

panic. In the end, they decided to wait until the morning, and when July

22 dawned with a heavy rain that lasted all day, further thought of

pursuit was abandoned. There was glory enough for one day.

Even as the Confederates exulted in their achievement, they also

counted their losses, and they were not inconsiderable. The combined

armies lost 387 killed and 1,582 wounded, many of whom would later die.

Some dozen or more were also missing, and probably dead, making total

casualties nearly 2,000. Considering that several units never reached

the fighting, like the commands of Holmes, Ewell, Longstreet, and more,

only about 17,000 Confederates were actually engaged. Thus casualties

came to about 12 percent of those engaged, yet in Bee's brigade they

were 16 percent, and in some of Jackson's Virginia regiments they ran as

high as 30 percent, testimony to how the stone wall had stood. And Bee

and Bartow were dead or dying, Smith was wounded, Jackson nursed a

finger nearly severed by a bullet. Half a dozen regimental commanders

were killed or wounded. Incredibly, Nathan Evans survived unscathed, to

boast—with excellent justification—that there was "no use for

other Generals to brag about what they did in the battle—that he

inaugurated that fight, he and Gen. Bee fought it through and he and

Bee whipped the fight before any reinforcements came." He was nearly

right. Evans saved the Confederate army that morning, buying the time

for Jackson and the others to arrive. Johnston contributed by staying

behind the lines constantly hurrying forward fresh units and sending

them always to the threatened left. Beauregard served mainly as a

personal presence and inspiration, though he gave little direction to

the actual fighting. The unit commanders on the spot seem to have done

most of that. As for the soldiers themselves, they behaved with

seemingly incredible discipline considering that they were volunteers in

their very first action.

|

THE LETTERS OF J. W. REID

Private J. W. Reid of the Fourth South Carolina Infantry wrote

several letters to his family between July 23 and July 30, 1861, from

the vicinity of the first Manassas battlefield. The following is a

compilation of four letters excerpted from Reid's book, History of

the Fourth Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers (pp. 23-28), first

published in 1891 and reprinted in 1975 by the Morningside Bookshop,

Dayton, Ohio.

I cannot give you an idea of the terrors of this battle. I believe

that it was as hard a contested battle as was ever fought on the

American continent, or perhaps anywhere else.

|

I scarcely know how to begin, so much has transpired since I wrote

you last; but thank God I have come through it all safe, and am now here

to try and tell you something about the things that have just happened.

As you have already been informed, we were expecting a big fight. It

came; it is over; the enemy is gone. I cannot give you an idea of the

terrors of this battle. I believe that it was as hard a contested battle

as was ever fought on the American continent, or perhaps anywhere else.

For ten long hours it almost seemed that heaven and earth was coming

together; for ten long hours it literally rained balls, shells, and

other missiles of destruction. The firing did not cease for a moment.

Try to picture yourself at least one hundred thousand men, all loading

and firing as fast as they could. It was truly terrific. The cannons,

although they make a great noise, were nothing more than pop guns

compared with the tremendous thundering noise of the thousands of

muskets. The sight of the dead, the cries of the wounded, the thundering

noise of the battle, can never be put to paper. It must be seen and

heard to be comprehended. The dead, the dying and the wounded; friend

and foe, all mixed up together: friend and foe embraced in death; some

crying for water; some praying their last prayers; some trying to

whisper to a friend their last farewell message to their loved ones at

home. It is heartrending. I cannot go any further.

Mine eyes are damp with tears. Although the fight is over the field

is yet quite red with blood from the wounded and the dead. I went over

what I could of the battlefield the evening after the battle ended. The

sight was appalling in the extreme. There were men shot in every part of

the body. Heads, legs, arms, and other parts of human bodies were lying

scattered all over the battlefield.

I gave you the particulars of our fight as best I could under

existing circumstances. I still have a strong presentiment that I will

be home again, some time. It may be a good while, and there is no

telling at present what I may have to go through before I come, if I do

come, only that I will have to encounter war and its consequences.

Yours as ever,

J. W. Reid

|

BATTLE OF BULL RUN (LC)

|

|

Several miles north in Centreville. the scene could not have been

more different. McDowell was dejected, and most of his army with him.

Their losses had been high, at least 460 killed, 1,124 wounded, and

1,312 missing, many of them killed and the rest prisoners of war. That

came to at least 2,896 casualties. Hunter and Heintzelman were wounded,

though neither mortally, and several regimental commanders would lead no

more. McDowell, in fact, planned a better battle than Beauregard, and he

took the initiative first. But he expected too much of his raw troops

in moving over unfamiliar ground, he squandered valuable time through

faulty reconnaissance, and then in the battle itself he made the mistake

that commanders in this war would commit repeatedly of using his

troops piecemeal, virtually abandoning his numerical advantage. No one

could fault him for the panic.

|

SOLDIERS' GRAVES NEAR SUDLEY CHURCH. (LC)

|

In Washington itself people could not believe what had happened. At

the first news both Lincoln and Scott refused to credit the rumors. Only

when they began to see the thousands of leaderless, dejected soldiers

streaming into the city streets did they realize the verity and reality

of the defeat. "It's damned bad," a dejected Lincoln told a congressman.

The same feeling spread across the Union, made the worse when newspapers

published the lists of the killed and missing. Suddenly the war came

home to the home front. It was no longer to be a summer's lark. The war

would go on, and perhaps on and on, and now they had a taste of its grim

flavor.

Jubilation swept the Confederacy, predictably. Editors and

politicians proclaimed that the one battle of the war had been fought.

Thus chastised, the Yankees would fight no more, and Southern

independence was virtually achieved. Indeed, a wave of overconfidence

crested on the victory, and for a time Confederates would be almost

complaisant. But then in time they saw not that the Union was pulling

out of the conflict. Instead, they saw an even larger and better

organized and equipped Yankee army staring to form in and around

Washington, this one commanded by a "Young Napoleon" named George B.

McClellan in whom the North seemed to have confidence. Out in the

western theater of the conflict along the Mississippi the Federals were

still planning what looked like preparations for a move against New

Orleans by Captain David G. Farragut and against the Mississippi by

General U. S. Grant. Perhaps it would not be such a short war after

all.

|

RETREATING UNION TROOPS PASSED OVER THE LONG BRIDGE INTO WASHINGTON.

(BL)

|

|

SOLDIERS' GRAVES ON BULL RUN BATTLEFIELD. (LC)

|

|

CANNONS AT MANASSAS NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD PARK. (NPS)

|

Among the men in the armies that bled over Bull Run, there were most

immediately other considerations. The men wrote home if they could. They

tended their wounds and mended their uniforms. Officers came and went,

some like McDowell discredited by defeat, while for others like Sherman

and Jackson and Beauregard there would be promotions and the beginnings

of legendary careers. And there came resolution on both sides. Win or

lose in this first battle, the soldiers who kept their heart—or

regained it after the panic—looked into themselves to see how they

would face their next battle, if there was to be one. Most agreed with

one Yankee private who told his family that "I intend to see the thing

played out, or die in the attempt.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

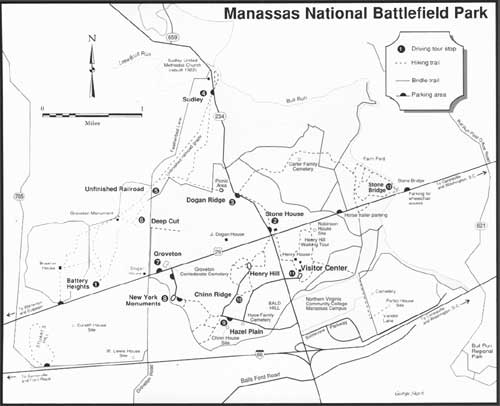

Manassas National Battlefield Park

|

|

Back cover There Stands Jackson Like a Stonewall, by Dick

Richardson, Box 107, Route 1, Bentonville, Virginia.

|

|

|