|

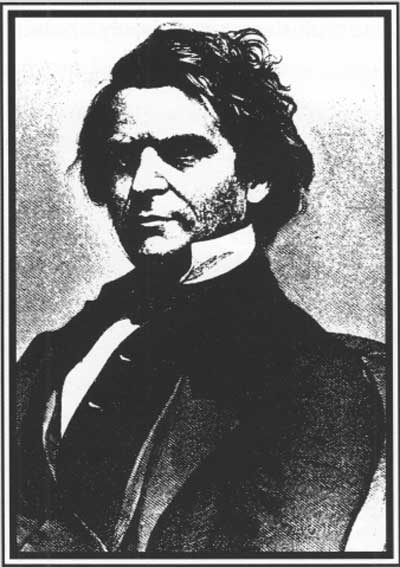

Irvin McDowell came from Ohio, was only 42, and had spent most of his

army career on staff duty. He was well liked but somewhat enigmatic. Men

found him humorless, distant, reticent. He was a teetotaler, but

otherwise a glutton who could finish every dish on a table and follow it

with an entire watermelon. Many thought him haughty and unpleasant. But

the governor of Ohio pushed him on Lincoln for a major command, and so

did Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase of Ohio. Incredibly, their

pressure resulted in McDowell being made a brigadier general with the

same seniority as Mansfield. When Scott was told to select a commander

for the Army of Northeastern Virginia being formed in Washington, he had

to choose between the two, and having other work in mind for Mansfield,

he had no choice but to give the plum to McDowell. Thus, through

politics, a man with no practical experience at all became the hope of

the Union's major army.

|

IRVIN MCDOWELL (LC)

|

Immediately upon assuming command, McDowell found himself called on

to produce a plan of action. Vainly he begged for time. He and his army

were "green," he pleaded, inexperienced. So they were, agreed Scott and

Lincoln, but so too were the enemy. They must move, and quickly. Late in

May, McDowell rode across the Potomac and established his headquarters

in and around Arlington, until recently the home of Robert E. Lee. At

once he began formulating his plan of campaign, though what had to be

done was obvious enough. Patterson must move against Harpers Ferry and

the Shenandoah to contain Johnston, while McDowell would move along the

line of the Orange & Alexandria. He would take Manassas Junction

with an army of 35,000 men and, he hoped, without a fight. McDowell knew

that Beauregard had fortified the Manassas Junction and Bull Run fords

and that it would be costly to force crossings there. Though he refined

and evolved his plans as the campaign progressed, McDowell would

eventually decide to march toward Bull Run, occupy Confederate attention

with feint moves against the fords, and meanwhile move a large column

across the stream some distance upriver at an unguarded ford. Then his

column could move down the south bank of Bull Run, striking the

Confederates on their exposed flank, and virtually forcing them to fall

back from the other fords and the Warrenton Turnpike bridge to avoid

being overwhelmed. Once the balance of his army was safely across Bull

Run, then he could move on Manassas and overwhelm Beauregard's 22,000 or

so Confederates. He would march on the morning of July 16.

|

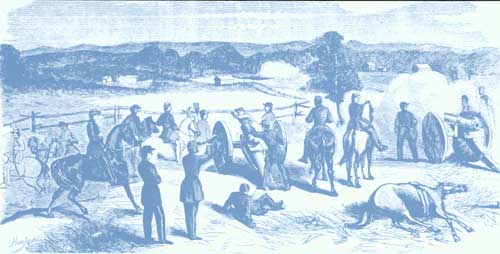

PICNIC BASKETS AND PARASOLS

Like many battles, First Manassas left in its wake civilians whose

lives were affected by the conflict. Present on that day was a small

assemblage of sightseers who had hoped to view the battle as one would

a spectator sport. What was actually observed, however, would forever

change these casual attitudes toward war.

This group of curiosity seekers that had come out from Washington

City was composed of civilians, reporters, and politicians. They came

with the belief that there existed no personal danger due to the rout

that would occur when the Confederates caught mere sight of the Union

army.

|

LISTENING FOR THE FIRST GUNS AT MANASSAS. (BL)

|

The majority of the group reached only as far as Centreville, five

miles to the east of Manassas Junction. Here they picnicked while

listening to the thunder of the distant battle and watching the smoke

rise above the trees. One of these bystanders was a British reporter,

William Howard Russell. He describes the audience and the scene before

them in his diary:

"Clouds of dust shifted and moved through the forest; and through the

wavering mists of light blue smoke, and the thicker masses which rose

commingling from the feet of men and the mouths of cannon, I could see

the gleam of arms and the twinkling of bayonets.

"On the hill beside me there was a crowd of civilians on horseback,

and in all sorts of vehicles, with a few of the fairer if not gentler

sex. A few officers and some soldiers, who had struggled from the

regiments in reserve, moved about among the spectators and pretended to

explain the movements of the troops below, of which they were

profoundly ignorant."

After many hours of fighting the Union army was finally forced to

retreat. Another reporter, Henry Villard, was among the soldiers that

began an orderly retreat, yet, as is written in his memoirs, were

"reduced to the condition of a motley, panic-stricken mob. . . .The

morale of the army was gone, and the instinct of self-preservation alone

animated the flying mass."

|

CONGRESSMAN ALFRED ELY

|

One of the spectators that would learn the hard way that war was not

an entertaining event was New York Congressman Alfred Ely. He had come

to see for himself how the Thirteenth New York Volunteer Infantry, made

up primarily from his district, were faring. He remained with the group

at Centreville a short time and then, growing bored with such

observation, ventured even closer to the battle. East of the Stone

Bridge he was discovered by the Eighth South Carolina and barely missed

being shot by Colonel E. B. C. Cash, who, pointing his pistol at Ely's

head, shouted, "God damn your white livered soul! I'll blow your brains

out on the spot!" Ely was spared by the intervention of the soldiers

present, captured as a prisoner of war, and sent to prison in Richmond,

serving five months before he was released. In his journal, kept during

his incarceration, Ely contemplates the folly of pursuing those

activities that lead up to his capture:

"Among other things, I found that to visit battle-fields as a mere

pastime, or with the view of gratifying a panting curiosity, or for the

sake of listening to the roar of shotted artillery, and the shrill music

of flying shells, (which motives, however were not exactly mine,) is

neither a safe thing in itself, nor a justifiable use of the passion

which Americans are said to possess for public spectacle."

|

Nothing in war goes as planned, and especially when so many are so

inexperienced. McDowell suffered under many handicaps, not least his own

limitations as a commander. Then there was the complete lack of adequate

maps of the countryside, even though Manassas lay scarcely 30 miles from

Washington. Neither did he have any substantial cavalry to send out in

advance to reconnoiter the ground. As a result, he would be moving

largely in the dark as to the countryside ahead of him, dependent on

local civilians who might or might not give him accurate information.

Equally bad, Washington was filled with Southern sympathizers who

observed every movement of the army and assiduously collected military

gossip in the hotel lobbies and taverns. As a result, even before

McDowell's men put out their campfires and marched south on July 16,

word had already reached Beauregard of their coming and their

intentions.

Early that morning the Yankee soldiers arose, expectant, excited,

determined that the march begun that day would take them "on to

Richmond" before the summer expired. Yet delay dogged them from the

start. Supposed to move in the morning, they did not get under way until

two in the afternoon. Their bands played martial airs, including

"Dixie," which at this stage was still popular on both sides, and "John

Brown's Body." The afternoon proved hot and humid, as all of the days

ahead would be in the northern Virginia summer. Men started breaking

ranks at every source of water, despite their officers' orders. No

blackberry bush could be passed without men stopping to strip it while

their comrades marched on. Quickly the generals saw just how "green"

this army in fact was. Some would conclude that it was little more than

a well-intentioned organized mob.

|

ADVANCE OF THE FEDERAL ARMY AS THE BATTLE OF BULL RUN OPENS.

(ILLUSTRATION FROM THE SOLDIER IN OUR CIVIL WAR)

|

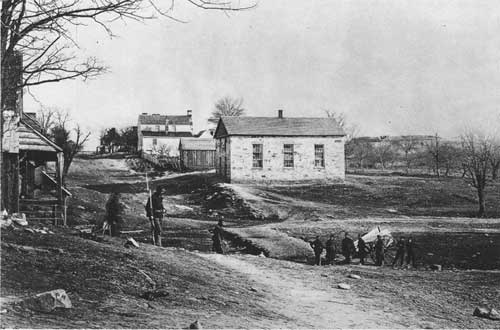

As a result they covered only a few miles that day. They did better

on the morrow, though, and by nightfall of July 17 portions of the

Yankee army had reached and taken Fairfax Court House. Still, McDowell

knew that his movements were well observed by the enemy now. There was

no chance to surprise Beauregard, and he expected that he would probably

encounter stiff resistance at Centreville, a few miles north of Bull

Run. Thus he ordered Tyler's division to attack that place early on July

18 before Beauregard could consolidate a defense, but when Tyler arrived

expecting a fight, he discovered that the Rebels had pulled back.

Beauregard, heavily outnumbered, had pulled all of his army back to the

south side of Bull Run. He would make his stand there and hope that he

could stop the Yankees' advance. Tyler was elated. The Federals had

taken the first feared obstacle without a skirmish. The enemy was

retreating in their front. At this rate, they might just push on to

Richmond and all be heroes. Since McDowell had given Tyler orders to

push forward to "observe well the roads to Bull Run," Tyler pushed

forward on the road that led to Blackburn's Ford.

The ground destined to become the Bull Run battlefield ran more than

eight miles along the stream, from northwest to southeast, commencing at

Sudley Ford nearly seven miles west of Centreville. Thereafter came in

downstream succession the stone bridge over the Warrenton Turnpike,

Lewis' Ford, Ball's Ford, Mitchell's Ford, Blackburn's Ford, McLean's

Ford, and at the end of the line the rail road bridge of the Orange

& Alexandria line. Beauregard had scattered his brigades out along

these crossings from Stone Bridge to the last ford, ignoring Sudley for

the time being. Blackburn's Ford stood almost in the center of the line,

and there he stationed Longstreet and his Virginians, who now awaited

the coming of Tyler. The Yankee general rode forward toward Blackburn's,

and thanks to the heavy woods and underbrush on the south side of Bull

Run, he could not detect any appreciable number of Confederates.

|

UNION SOLDIERS AT CENTREVILLE. VIRGINIA, LOCATED ABOUT FIVE MILES FROM

MANASSAS, (LC)

|

|

SUDLEY SPRINGS FORD AND THE SUDLEY METHODIST CHURCH ON THE HILLTOP. (LC)

|

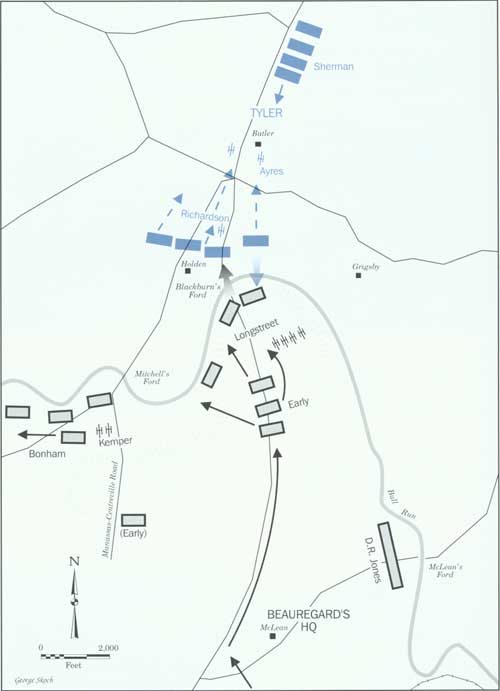

Immediately Tyler thought he saw an opportunity. If he rushed across

Blackburn's Ford he could move straight on Manassas Junction and seize

it, accomplishing one of the main objectives of the campaign, seemingly

without meeting resistance. Despite McDowell's orders to do nothing more

than reconnoiter—and under no circumstances to bring on an

engagement—Tyler ordered the brigade of Colonel Israel Richardson

to come forward at once. A brief artillery duel ensued, and then Tyler

sent forward his first regiment, driving toward the ford.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE BATTLE OF BLACKBURN'S FORD, JULY 18, 1861.

Brigadier General Daniel Tyler orders Colonel Israel B. Richardson's

brigade to probe the Confederate position along Bull Run. As

Richardson's men approach Blackburn's Ford they come under fire from

Confederates concealed along the wooded bank. With the Confederate fire

growing more intense and realizing he has gotten more than he bargained

for, Tyler orders his men to withdraw. General James Longstreet sends

part of his brigade across Bull Run to pursue the retreating Federal

soldiers. The pursuit covers a short distance before the Confederates

are recalled back across the stream.

|

For the next hour that regiment engaged with Confederate artillery

and resistance from sharpshooters, in spite of Tyler's belief that he

faced few foemen in his front. Then he sent in the rest of Richardson's

brigade, and soon the Yankee line swept down the sloping ground toward

the bank of Bull Run. What they met was stiff resistance, some of it

from unseen Rebels posted on the north side of the stream, and in the

end Tyler's artillery was forced back with some losses soon to be

followed by the infantry. Now Tyler decided that his idea of easily

crossing and pushing on to Manassas was out of the question. He had

reconnoitered, found the enemy in sufficient strength to know that

McDowell could not cross easily here, and had nothing more to do.

Unfortunately, it proved not to be so easy to pull men out of battle as

to send them in. One of Richardson's regiments was already charging as

Tyler issued his withdrawal order, and then another went in to support

it, and the battle continued to develop in spite of Tyler's desire to

pull out. Worse, the Yankees were getting the worst of it.

|

LT. PETER HAINS FIRED THE BATTLE'S OPENING SHOT WITH A 30-PDR. PARROTT

RIFLE, AFFECTIONATELY REFERRED TO BY HIS MEN AS "LONG TOM." (HARPER'S

WEEKLY)

|

|

THROUGHOUT THE BATTLE, MEN OF BOTH SIDES SOUGHT SHELTER IN AND AROUND

THE STRONG WALLS OF THE STONE HOUSE, AN AREA LANDMARK SINCE THE 1820.

(LC)

|

Across Bull Run, Beauregard had expected the Federals might try a

crossing at Blackburn's Ford, Longstreet had been ready. He carefully

concealed his regiments in the woods and brush and that morning allowed

the men a leisurely breakfast despite suspecting that they might be

fighting before long. Men said the Lord's Prayer over and over again,

threw away their dice and playing cards, repented their sins, and

otherwise tried to square themselves with the Maker in case they should

fall in the fight. When Tyler's advance parties first appeared and

commenced their artillery fire, inexperienced soldiers initially thought

the sound of cannon balls flying overhead was the sound of horses

whinnying. They soon learned otherwise, however, and initially

Longstreet's line wavered until he personally rode along its rear, sword

drawn, whacking it on the backs of men thinking of fleeing. His example

helped steady them before the next two infantry assaults came at them.

Jubal Early in reserve sent reinforcements. and together they held their

ground, driving off the last of Tyler's Yankees.

|

|