|

|

THE SAGA OF WILMER MCLEAN

Nestled among corn fields and pasture lands in rural Prince William

County was a large plantation known as Yorkshire. Wilmer McLean and his

wife, Virginia Beverly Hooe Mason, moved there in January of 1853,

completely unaware of the events that would transpire at their estate

shortly after the beginning of the Civil War.

During the First Battle of Manassas, the McLean House was used as

headquarters for General P.G.T. Beauregard, commander of the

Confederate Army of the Potomac. Edward Porter Alexander, a relative of

Wilmer McLean and Beauregard's chief signal officer, witnessed the

beginning of the battle from McLean's yard. The barn was used as a

military hospital, as well as a prison for captured Union soldiers. A

log kitchen on the property received damage from Union artillery fire on

July 18, 1861. Reportedly, a shell went through the walls of the

kitchen, causing mud daubing to fly into the dinner of Confederate

officers dining there.

|

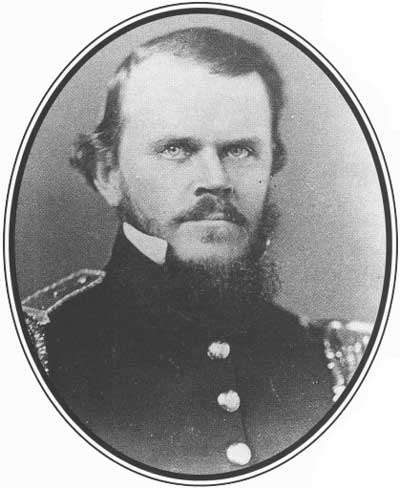

WILMER MCLEAN (NPS)

|

McLean, concerned for his family's safety, took them away from

Yorkshire before the beginning of the battle, but he would return after

the fighting was over. He remained in Manassas and worked for the

Confederate quartermaster through February 28, 1862. He would not be

reunited with his family until the spring,

When the Confederate army evacuated the Manassas area in March 1862,

McLean's business opportunities dwindled. He and his family left

Yorkshire, eventually settling in the south-central Virginia community

of Appomattox Court House by late 1863, He could not escape the war,

however. On April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of

Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant in the parlor of the McLean

home.

|

For McDowell's sake, it may have been a good thing that he knew

nothing of what had been happening out in the Shenandoah or in his front

across Bull Run. Already his own plans were coming apart. He did not

want Tyler to make such a heavy demonstration as that at Blackburn's

Ford, for now he feared that Beauregard would reinforce that section of

Bull Run. Worse, upon reaching the vicinity he had to change his

original plan of advance and not attempt to cross Bull Run at the lower

ford near the Orange & Alexandria tracks, then sweep northwestward

up the south bank. Reconnaissance now showed him that the ground was

not suitable to moving large numbers of troops.

As a result, McDowell spent all of July 19 in reconnoitering other

ground and in resting his men. His scouts learned that the stone bridge

was heavily guarded but that Sudley Ford was protected by only a few

companies of the enemy, so confident was Beauregard that McDowell

intended to attack in the center of his line. The trouble was that there

were no good, direct roads to the ford, but McDowell's staff set about

interviewing local farmers and eventually found a practicable—if

difficult—route that infantry might take. Learning this, McDowell

revised his battle plan even while his men heard and speculated on the

meaning of the sound of trains coming into Manassas Junction. Some

thought it was the sound of the Confederate army evacuating and that

there would be no battle. Others, like brigade commander Colonel William

T. Sherman, thought otherwise and expected to meet the combined enemy

armies when the battle came. When word came to McDowell that Beauregard

and Johnston had joined, though, he refused to believe it. Washington

would have informed him if Patterson had failed, he reasoned. What

neither he nor Washington knew yet was that Patterson himself did not

yet realize that Johnston had disappeared from Winchester.

|

ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY OF SHERMAN'S LIGHT ARTILLERY

BATTERY.

|

Late on July 20, McDowell called a war council with his staff and

division commanders and explained to them his plans based on new

information. Tyler was to make demonstrations along the lower fords from

the stone bridge on down, while Hunter was to make the difficult

cross-country march to Sudley Ford and cross there. Heintzelman was to

cross at a nearby ford but would miss his way and eventually follow

Hunter. Together they would then sweep down the south bank of the

stream, opening each succeeding ford as they moved. Ironically, his

plan was exactly the same as Beauregard's; stand firm in the center and

left and make a massive move on the right. McDowell's was the better

conceived of the two because he aimed at the easier fords to cross and

made use of the apparent fact that Beauregard's main strength was on the

center and lower crossings. Still, it was the army that moved first that

would have the advantage.

On both sides men wrote their names and home towns on slips of paper

and pinned them to their shirts or put them in a pocket so that, should

they fall, their bodies could be identified and sent home.

|

That evening the men and officers all knew that there would be a

fight on the morrow. "We shall have hard work, and I will acquit myself

as well as I can," Sherman wrote home. Out around the campfires rumors

flew from mouth to mouth. Those who could enjoyed a beautiful evening,

especially appreciated after the oppressive heat of the day. Out in the

fields the lowing of cattle and the rattling of the crickets in the

thickets lent a peaceful air to what was about to become a scene of

battle. Bands played patriotic songs. Across Bull Run the scene was the

same, only the soldiers rejoiced that the two armies had become one. On

both sides, North and South, they looked forward to routing the foe in

the morning. On both sides men wrote their names and home towns on slips

of paper and pinned them to their shirts or put them in a pocket so

that, should they fall, their bodies could be identified and sent home.

They all knew, blue and gray alike, that some of them were destined to

die.

|

"YOU AND MOTHER NEED NOT FEAR THEM, . . ."

"Should troops he passing about the neighborhood you and mother need

not fear them, as your entire helplessness, I should think would make

you safe." On May 30, 1861, Hugh Fauntleroy Henry would write these

words in a letter to his sister Ellen. Almost two months later, on July

21, those words would prove too hasty. Although many civilians living on

and around the battle field were directly affected by First Manassas,

the Henry family in particular would stand out among the others in their

loss and tragedy. At the time of the battle, Henry Hill (then known as

Spring Hill Farm) was owned by Mrs. Judith Carter Henry, an

eighty-five-year-old widow confined to her bed. She lived there with her

daughter, Ellen Phoebe Morris, and was often visited by her sons John

and Hugh. Due to her infirmity the fields surrounding the house lay

fallow and it would be in these fields that the first major land battle

of the Civil War would be decided. As the approach of the Union troops

became imminent, Mrs. Henry's daughter Ellen and son John tried to move

her to a neighboring residence. On the way, the sound of gunfire and

smell of smoke frightened Mrs. Henry into demanding that they return her

to her own home. Shortly after her return Union artillery took position

on either side of the Henry home. In an attempt to dislodge Confederate

sharpshooters located there, Captain James B. Ricketts turned his guns

on the house and fired, mortally wounding Mrs. Henry. Different sources

conflict in numbering her wounds from one to thirteen. Her daughter,

Ellen, had hidden herself in the fireplace, and while sustaining no

injuries, the reverberations from the exploding shells caused her to

lose part of her hearing. Mrs. Henry's son, John, escaped injury as it

is believed he was outside the house during the artillery barrage. A

servant of Mrs. Henry received minor wounds. Mrs. Henry, the only

civilian death of this battle, was buried the next day in the yard

beside her house.

|

HENRY HOUSE AFTER THE BATTLE (LC)

|

|

GRAVE OF JUDITH CARTER HENRY AT MANASSAS NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD PARK.

(NPS)

|

|

Predictably, the Federal plan started to go wrong from the moment it

commenced the next morning. No one bad any experience of trying to move

troops in these numbers, over unfamiliar ground, on narrow or barely

existent roads. Moreover, these were volunteers, still unfamiliar with

their orders and drum and bugle calls and not entirely adjusted yet to

some wet-eared corporal or sergeant bawling orders at them. McDowell

wanted to start his march at 2 A.M. Schenck's brigade, the first to

depart, did not start until an hour later. Then the going proved

difficult in the dark, the men sometimes actually feeling their way, and

moving thus at a snail's pace. It took an hour to cover just the first

half mile, thus delaying Sherman's brigade immediately behind. Tyler did

his best to push these men forward, but still it would be nearly

daylight before they covered the short distance to the north bank facing

the stone bridge. And the slowness of their movement naturally slowed

Hunter and Heintzelman, who for a time had to march behind them before

they could turn off on the path to Sudley Ford. Having much farther to

go to reach their destination, they should have been ordered to move out

first.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

MCDOWELL ATTEMPTS TO FLANK THE CONFEDERATE LEFT (5:30-9:00 A.M.)

On the morning of July 21, General McDowell orders half

of his army around the left flank of the Confederate line posted along

Bull Run. The divisions of Colonels David Hunter and Samuel P

Heintzelman turn off the Warrenton Turnpike and head north toward Sudley

Ford. Meanwhile, General Daniel Tyler's division creates a diversion at

the stone bridge. Colonel Nathan "Shanks" Evans's Confederate brigade

overlooking the bridge receives word of the Federal flanking column

moving north of their position. Wasting no time, Evans hurries his men

to Matthews Hill.

|

Facing them on the south side of Bull Run, and concealed on hills

immediately overlooking the stone bridge, was the small command of

Colonel Nathan G. Evans, one of the true eccentrics of the Confederate

army. The South Carolinian was boastful, swaggering, and hard-drinking.

He detailed an orderly on his staff to carry with him at all times a

small keg of whiskey that he called his barrelita, and from which he

took numerous draughts during a day. Yet he was also a born fighter. He

would scrap with anybody, including his own superiors, but most of all

he would prefer to fight with the Yankees, and on this, his first

opportunity, he would prove himself a terror.

|

THE BATTLE OPENED IN EARNEST ON MATTHEWS HILL. WARTIME HOME TO BROTHERS

EDGAR AND MARTIN MATTHEWS. (LC)

|

Evans had only the Fourth South Carolina and the First Louisiana

Battalion, two cannon, and a company of cavalry—essentially a

regiment and one-half, to face Tyler's entire division. Lesser men would

have recoiled when they saw the advance elements of the Yankees

approach. When Tyler's artillery sent their first shot across Bull Run

just after 6 AM., intending it as a signal to McDowell that they were in

position, and at the same time expecting their fire to pin down

Confederates at the bridge, Evans refused to be duped. He kept his own

guns silent, not wanting to reveal to Tyler just how weak he was, and

only let a small line of skirmishers return a sporadic fire. Thus Tyler

had no inkling that he could have pushed across the bridge with one

concerted thrust.

By 7:30 Evans deduced that Tyler had no intention of attacking.

Obviously this was only a demonstration, and that could mean just one

thing. Tyler wanted to keep him here and divert his attention from

something else. Soon thereafter Evans discovered what that was, as a

report came in that the Yankees had been seen off to his left heading

toward and even crossing Sudley Ford.

|

NATHAN G. EVANS (SOUTH CAROLINA LIBRARY)

|

As frustrating as was the morning's march for Tyler, it was worse for

Hunter and Heintzelman. Hunter waited a full two and one-half hours for

Tyler's division to get out of the way before he could start his march

in the dark. Colonel Ambrose Burnside's brigade led the way at last, but

it was 5:30 before he finally reached the turnoff for Sudley Ford. Then

the "road" turned out to be nothing more than a path, and some men had

to cut down trees and brush to clear the way for the rest. The sun

started to rise in the sky, elevating the temperature uncomfortably even

though it was still morning. It was going to be hot, humid, and they

were running very, very late. When Tyler's signal cannon sounded,

Burnside was still three miles from the ford. Then a guide took them off

on the wrong fork of the road that added

another—unnecessary—three miles to their march. As a result,

it was 9:00 before Burnside's advance parties finally cleared the woods

and saw the stream and ford nearly a mile ahead. When they reached Bull

Run, the bluecoats were so parched that they broke ranks and gulped

water from the stream despite their officers' orders to keep formation.

Then they crossed, with the sounds of Tyler's sporadic skirmish off to

the left suggesting that the battle was already under way. What they

could not know was that the scrappy Nathan Evans was on the way,

too.

|

|