|

THE PEA RIDGE CAMPAIGN

Early in 1861 representatives from seven southern states met in

Montgomery, Alabama, and formed the Confederate States of America. In

the weeks that followed, United States military posts, arsenals, and

government buildings were seized all across the nascent Confederacy.

Arkansas remained in the Union during this unsettled period, but there

was widespread enthusiasm for secession. There also was widespread

concern that the United States government would attempt to reinforce the

state's two military posts, the Little Rock Arsenal and Fort Smith, to

prevent their seizure by secessionists.

|

GOVERNOR HENRY RECTOR (UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS AT LITTLE ROCK ARCHIVES)

|

At the beginning of February the state was swept by rumors that

Federal troops were on their way up the Arkansas River to reinforce the

tiny garrison at the Little Rock Arsenal. About a thousand militiamen

rushed to the state capital to repel this imaginary force. Governor

Henry M. Rector, an ardent secessionist, saw an opportunity to push

Arkansas one step closer to leaving the Union. He assumed command of the

militia and called upon Captain James Totten to surrender the arsenal.

Totten was well aware that his company of Federal artillerymen could not

possibly hold off Rector's armed mob. He therefore agreed to

evacuate—though not to surrender—the post in order "to avoid

the cause of civil war." A few days later the Federal garrison marched

down to the Arkansas River to the cheers of a huge crowd. The ladies of

Little Rock presented Captain Totten with a sword for his chivalric

behavior. The artillerymen then boarded a steamboat for St. Louis. After

suitable celebrations, the militiamen returned to their homes.

Rector waited until the outbreak of fighting at Fort Sumter, South

Carolina in April before dealing with Fort Smith, a supply depot on the

border between Arkansas and the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

He sent several hundred militiamen up the Arkansas River on steamboats

to seize the post, only to discover that the Federal garrison—two

companies of cavalry commanded by Captain Samuel D. Sturgis—had

evacuated the place and marched to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Without

firing a shot, Arkansans had rid the state of Federal military forces,

such as they were. On May 6, a special convention met at the State House

in Little Rock and voted in favor of secession. Shortly thereafter,

Arkansas joined the Confederacy along with three other slave states in

the upper south, North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee.

|

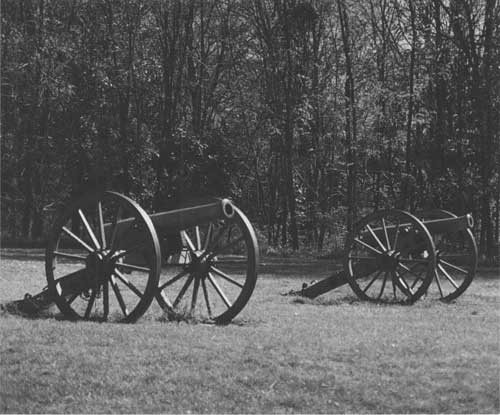

CONFEDERATE ARTILLERY STAND GUARD AT PEA RIDGE NATIONAL MILITARY PARK.

(NPS PHOTO BY BOB NORRIS)

|

Arkansas was the least populous and least developed state in the

Confederacy. With relatively few people and little in the way of natural

resources, it seemed unlikely that any significant military activity

would take place in what was essentially a frontier region.

Nevertheless, both the Arkansas and Confederate governments did what

they could to get the state onto a war footing. The Arkansas-Missouri

state line now was the border between the United States and the

Confederate States west of the Mississippi River, so it was essential

that military forces be stationed in northern Arkansas. Most regiments

raised in Arkansas were rushed eastward to Tennessee (one regiment even

ended up in Virginia at the opposite end of the Confederacy), but Rector

convinced Confederate authorities to keep some troops from Arkansas and

adjacent states at home to defend the huge area that came to be known as

the Trans-Mississippi.

Confederate soldiers massed in northeast and northwest Arkansas, the

two most likely points of invasion. Brigadier General William J. Hardee

commanded a force near Pocahontas, but within a few months he and his

men were transferred to the east side of the Mississippi River and never

returned. That left only one Confederate army in Arkansas, a force of

8,700 Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana troops at Fort Smith. The commander

of this army was Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch of Texas.

McCulloch, 50, was a veteran of the Texas Revolution, Mexican War,

and two decades of frontier service in the Texas Rangers. Though he

lacked a formal military education, he was an able administrator,

strategist, and tactician who took good care of his men. McCulloch's two

principal subordinates were Brigadier General James M. McIntosh and

Colonel Louis Hebért. Mcintosh, 34, graduated last in his class at West

Point and served for years on the frontier fighting Indians. Courageous

to a fault, he liked nothing better than plunging into a fight. McIntosh

was in charge of the army's mounted troops. Hebért, 41, was a highly

regarded West Point graduate and civilian engineer from Louisiana.

Capable and popular, Hebért commanded the infantry.

McCulloch knew that he could expect no help from the east side of the

Mississippi River if the Yankees made a move in his direction. His

isolated little army would have to fend for itself. To complicate

matters even more for McCulloch, the defense of Confederate Arkansas

depended on events in neighboring Missouri.

|

THE UNITED STATES ARSENAL AT LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS, FEBRUARY 1861.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY, MARCH 1861)

|

The political and military situation in Missouri during the first

year of the Civil War was highly fluid and not a little confusing.

Missouri was a slave state, but only a small proportion of the state's

population owned slaves or advocated secession. Though pro-secessionist

forces were outnumbered, they had the initial advantage of dominating

the state government and the state militia, known as the Missouri State

Guard.

The Missouri State Guard was commanded by Sterling Price, 53, a

popular politician who had served as a legislator, congressman, and

governor. Price had no formal military training but had performed

reasonably well in New Mexico during the Mexican War. Almost as soon as

the Civil War began, however, Price's shortcomings as a military leader

became evident. These included an abrasive and insubordinate

personality, a lack of administrative and tactical skills, and a

tendency to see the war entirely in terms of liberating Missouri from

Yankee oppression.

Price's Missouri State Guard was the only true militia army of the

Civil War. The ragtag organization consisted of somewhere between 6,000

and 8,000 men, depending on season and circumstances, but it always was

seriously deficient in organization, training, and logistical

support.

|

Price's Missouri State Guard was the only true militia army of the

Civil War. The ragtag organization consisted of somewhere between 6,000

and 8,000 men, depending on season and circumstances but it always was

seriously deficient in organization, training, and logistical support.

Volunteers came and went as they pleased and provided their own

clothing, camp equipment, and weapons. Discipline was lax to

nonexistent.

The Union military commander in Missouri was Brigadier General

Nathaniel Lyon, a fiery regular soldier who was determined to rid the

state of the troublesome Rebels once and for all. During the spring and

early summer of 1861 Price and Lyon struggled for control of Missouri's

population centers and political institutions. A great deal of marching

and counter-marching was punctuated by small clashes at Boonville and

Carthage. By midsummer Lyon had forced the Missouri State Guard into the

southwest corner of the state and Union forces appeared to be on the

verge of a complete victory.

Price was in desperate straits and he called upon McCulloch for help.

This placed McCulloch in a difficult position because his mission was to

defend Confederate territory. But McCulloch recognized that the Missouri

State Guard played an important strategic role: it kept Missouri in

turmoil and served as a buffer between the Yankees and his own

Confederate army in Arkansas. McCulloch therefore edged into Missouri to

reinforce Price in his hour of need.

McCulloch's Confederate army and Price's Missouri State Guard settled

into camp along Wilson Creek a few miles south of Springfield. The

soldiers—westerners all—got along well enough, but not the two

commanders. Price's personality quickly began to wear on McCulloch, who

had little patience with political windbags. The deteriorating

relationship between the generals was to have a significant impact on

events.

Lyon was undeterred by news of McCulloch's movement into Missouri and

his juncture with Price. Despite being heavily outnumbered, he struck

the Rebel encampment along Wilson Creek on August 10, 1861. The Union

army had the initial advantage of surprise, but the weight of numbers

gradually turned the tide. At the close of the day Lyon was killed and

his little army was driven from the field. Among the Rebel guns that

contributed to the hard-fought victory at Wilson's Creek was the battery

Totten had abandoned at the Little Rock Arsenal six months earlier.

McCulloch was pleased at the outcome of Wilson's Creek but he was

uneasy at having entered Missouri—a foreign country from his

perspective—without instructions from the Confederate government.

McCulloch also realized that he could not long maintain his army atop

the Ozark Plateau so far north of his supply base at Fort Smith, and he

soon returned to northwest Arkansas. Another factor in his decision to

retire to Confederate soil was his exasperation with Price, whom he

privately disparaged as "nothing but an old militia general."

Exhilarated by the triumph at Wilson's Creek, Price marched north to

the Missouri River in hopes of igniting a popular uprising and filling

his ranks with new recruits. For Price the key to success was the region

in west-central Missouri known as "Little Dixie..."

|

In contrast to McCulloch, Price was a free agent unfettered by orders

from far-away Richmond or even nearby Jefferson City, which was firmly

in Union hands. There was no functioning Missouri state government at

this time and for all practical purposes Price was on his own.

Exhilarated by the triumph at Wilson's Creek, Price marched north to the

Missouri River in hopes of igniting a popular uprising and filling his

ranks with new recruits. For Price the key to success was the region in

west-central Missouri known as "Little Dixie," the strongly

pro-secessionist counties along the Missouri River between Jefferson

City and Kansas City.

After a two-day siege, the Missouri State Guard captured a small

Union garrison at Lexington on the south bank of the Missouri on

September 20. The Rebel victory threw a fright into Unionists all across

the state, but there was no discernible increase in the number of

volunteers for the State Guard. To make matters worse Price was unable

to sustain his command so far north and fell back to the Springfield

area.

During the fall of 1861 Major General John C. Frémont assembled

another Union army and made a second attempt to crush the Missouri State

Guard, but he was relieved in mid-campaign by President Abraham Lincoln,

who was displeased with Frémont's political machinations and lack of

administrative ability. In November a secessionist rump of the Missouri

legislature declared the state to be a part of the Confederacy. The

legitimacy of this act was dubious, to say the least, but it was accepted

by Confederate authorities in Richmond and a twelfth star was added

to the Confederate flag.

During the winter of 1861-62 the military stalemate in Missouri

continued. During this period of reduced activity the Missouri State

Guard experienced a partial transformation. Confederate president

Jefferson Davis promised Price a major general's commission if he raised

a division of Missouri troops, so Price pressured his followers to join

the Confederate army. Price was especially keen about obtaining the

commission, as it would enable him to outrank McCulloch, whom he now

regarded as his personal nemesis. Unfortunately for Price, only about

half of the militiamen volunteered for Confederate service; the rest

either remained in the State Guard or packed up and returned home.

Several months would pass before the disgruntled Missouri leader finally

received his Confederate stars. During the Pea Ridge campaign, Price was

a major general of Missouri militia in command of a hybrid force of

Confederate and Missouri State Guard troops, a situation unique in

Confederate military annals.

As the new year of 1862 dawned, McCulloch's Confederate army was in

winter quarters in northwest Arkansas several days' march south of

Springfield. The infantry was in well-built and well-stocked cantonments

in and around Fayetteville, Bentonville, and Cross Hollows; the cavalry

and artillery were in the Arkansas River Valley, fifty miles to the

south, where the army's horses and mules enjoyed warmer temperatures and

adequate forage. McCulloch had achieved a small miracle in arming,

equipping, and supporting his troops on the western edge of the

Confederacy. He was confident that his army would be ready for action

when the next campaigning season arrived.

McCulloch did not expect any serious military activity atop the Ozark

Plateau until spring, so he traveled to Virginia to confer with

President Davis about the state of affairs in the Trans-Mississippi,

including his antagonistic relationship with Price. After several months

of increasingly bitter wrangling, the two generals no longer were on

speaking terms and their armies, less than one hundred miles apart,

continued to operate independently of one another. With Missouri now a

nominal Confederate state, with Price on the verge of becoming a

Confederate major general, and with the spring campaigning season

approaching, McCulloch believed the situation west of the Mississippi

River had to be cleared up as quickly as possible.

Davis dealt with the problem by creating the District of the

Trans-Mississippi, a vast area consisting of Missouri, Arkansas, north

Louisiana, and the Indian Territory. McCulloch was the obvious choice to

command the new district, but Davis refused to consider the Texan for

the position because he was not a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy.

Despite considerable evidence to the contrary, Davis firmly believed

that no one could master the art of high command without the benefit of

a formal military education. After unsuccessfully offering command of

the Trans-Mississippi to several West Pointers, including Braxton Bragg,

Davis finally settled on Major General Earl Van Dorn of Mississippi.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

SOUTHWEST MISSOURI AND NORTHWEST ARKANSAS, JULY 1861 TO MARCH 1862

During the first twelve months of the Civil War, military operations

in the Trans-Mississippi swirled back and forth between the Boston

Mountains and the Missouri River. Confederate victories at Carthage,

Wilson's Creek, and Lexington kept secessionist hopes alive in Missouri

through the end of 1861, but everything would change in the new

year.

|

Van Dorn, 42, was a West Point graduate who had served with

distinction in Mexico and in the Indian wars on the Great Plains. His

principal qualification for command of the District of the

Trans-Mississippi, however, was his friendship with Davis. Van Dorn

hailed from Port Gibson, a town only twenty miles from Davis's

plantation on the Mississippi River, and the two men had known each

other for years. Davis had a tendency to appoint friends and

acquaintances to important posts, often without regard for

qualifications. Despite his background, Van Dorn proved to be a poor

choice for such an important assignment. Personally courageous, he also

was ambitious, impulsive, and reckless. And he was a ladies' man, a

fatal character flaw that led to his murder by an angry husband in

1863.

Van Dorn rushed westward from Virginia to his new post in Arkansas.

The new commander was extremely offensive-minded, something of a rarity

among generals of both sides in early 1862. He intended to recover

Missouri for the Confederacy at the first opportunity. Van Dorn reached

Little Rock in February, then moved to the northeast corner of Arkansas

and established a forward headquarters at Pocahontas, only twenty miles

south of the Arkansas-Missouri state line. It was both a symbolic and a

practical move. Symbolic because it reflected his intention to carry the

war to the Yankees, and practical because Pocahontas was a good

jumping-off point for an invasion of southeast Missouri on the most

direct route to St. Louis. When spring made operations atop the Ozark

Plateau feasible, Van Dorn planned to march north and strike the Yankees

a heavy blow. He provided his wife with a concise summary of his

strategic thinking: "I must have St. Louis—then Huzza!"

|

MAJOR GENERAL HENRY W. HALLECK (LC)

|

Lincoln, meanwhile, solved his own command problems west of the

Mississippi River by appointing Major General Henry W. Halleck to

succeed Frémont as commander of the Department of the Missouri. Halleck,

47, was the prewar army's premier intellectual who was known, somewhat

derisively, as "Old Brains." Though he did not cut a dashing figure,

Halleck was an able administrator and strategist who was determined to

reassert Union control over Missouri. He grasped the fairly obvious fact

that every Union soldier standing on the defensive in Missouri to

counter Price was one less soldier who could be used in the offensive

campaigns he planned to launch on the Tennessee, Cumberland, and

Mississippi Rivers. Halleck is generally depicted as a cautious and

indecisive bureaucrat, but forces under his overall command landed a

series of powerful blows against the western Confederacy during the

first six months of 1862.

Halleck believed it was imperative that Union forces in Missouri

seize the initiative and neutralize Price at once rather than wait for

more suitable weather. He hoped that a winter campaign would catch the

Rebels off guard. On Christmas Day 1861, he placed Brigadier General

Samuel R. Curtis in command of the Army of the Southwest, a force of

about 12,000 men. Curtis's mission was straightforward: he was to

destroy Price's army or drive it out of Missouri.

|

|