|

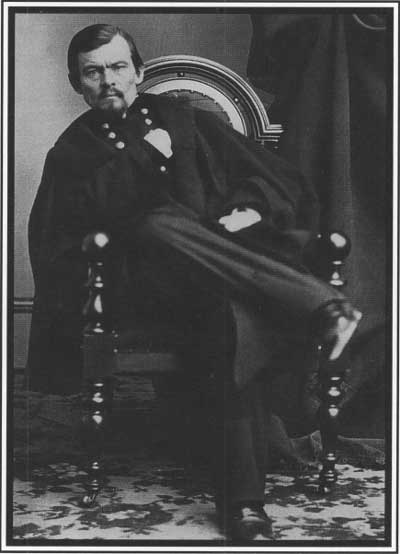

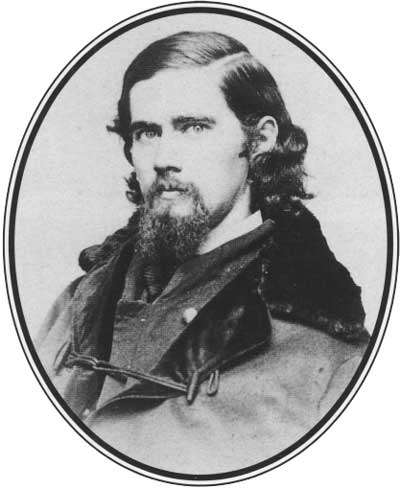

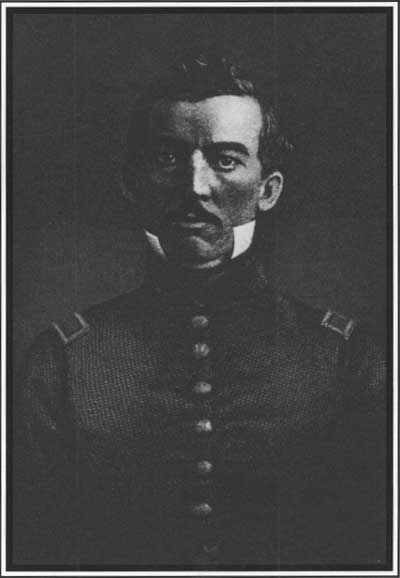

Curtis, 56, was a West Point graduate who had resigned from the army

and prospered modestly as a civil engineer, attorney, businessman, and

politician in the Midwest. He served capably as military governor of

Matamoras, Camargo, Monterey, and Saltillo during the Mexican War but

saw no combat. A man of many interests, he helped found the Republican

Party and was instrumental in the establishment of the Union Pacific

Railroad. When the Civil War erupted he resigned his seat in the House

of Representatives and raised an infantry regiment in his adopted state

of Iowa. Union commander in chief Major General Winfield Scott

remembered Curtis from the Mexican War and supported his promotion to

brigadier general. Scott's faith in Curtis was not misplaced. Despite

limited military experience, Curtis proved to be the most successful

commander on either side in the Trans-Mississippi.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

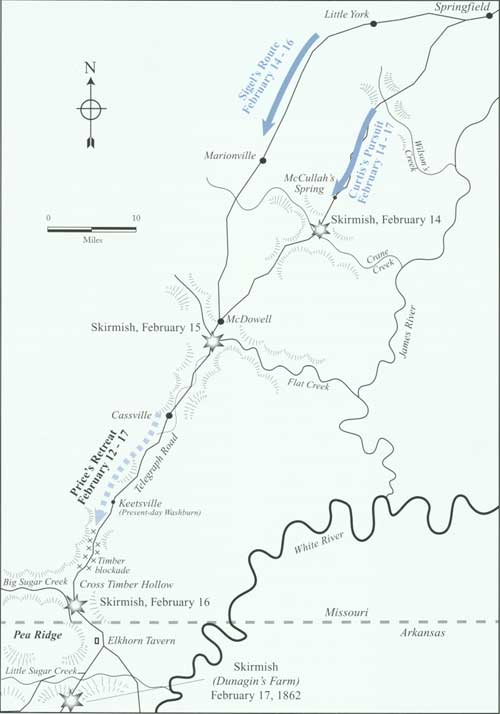

CURTIS DRIVES PRICE OUT OF MISSOURI, FEBRUARY 12 TO 17, 1862

Price abandoned Springfield on February 12 and hurried south on

Telegraph Road toward Arkansas. Curtis pursued with half of his army,

while Sigel led the other half on an unsuccessful attempt to block

Price's retreat at McDowell. The second phase of the pursuit was marked

by increasingly intense clashes, culminating in the fight at Little

Sugar Creek (Dunagin's Farm).

|

Halleck was impatient with the see-saw nature of the war in Missouri.

Every Union setback encouraged the secessionists and demoralized the

loyalists. Another unsuccessful campaign would have repercussions far

outside Missouri by delaying vital operations along the Confederacy's

vulnerable western waterways. "We must have no failure in this movement

against Price," he cautioned Curtis. "It must be the last." On this

point the two Union generals were in perfect agreement.

|

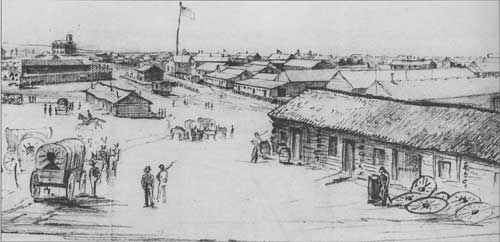

ROLLA, MISSOURI, IN 1862, THE RAILHEAD AND PRINCIPAL SUPPLY DEPOT

FOR UNION OPERATIONS IN THE OZARKS. (NPS)

|

Curtis hurried to the railhead at Rolla, one hundred miles southwest

of St. Louis, to begin preparations for the coming offensive. He had no

illusions about the difficulty of a winter campaign atop the Ozark

Plateau. The vast limestone uplift occupied the southern half of

Missouri and the northern half of Arkansas and was one of the most

rugged and sparsely settled regions in the country. To complicate

matters, every step toward Springfield would take Curtis farther away from

his supply base at Rolla.

Union armies in Virginia and Tennessee were largely transported

and supplied by steamboats and trains, but in Missouri and Arkansas

there were few navigable rivers and even fewer railroads.

|

Union armies in Virginia and Tennessee were largely transported and

supplied by steamboats and trains, but in Missouri and Arkansas there

were few navigable rivers and even fewer railroads. Atop the Ozark

Plateau there were none at all. The Army of the Southwest and its supply

wagons would have to proceed along primitive frontier roads, much as

American forces had done in northern Mexico fifteen years earlier.

Curtis stripped his command of unnecessary baggage, for he realized that

the Union troops would have to travel light and forage vigorously. He

requested an experienced quartermaster from the regular army and

obtained one in the person of Captain Philip H. Sheridan, a favorite of

Halleck's who would later go on to greater things.

In the process of organizing his embryonic army, Curtis encountered a

vexing ethnic problem. Roughly half of the troops in the gathering Army

of the Southwest were native-born Americans, generally of British stock,

who hailed from the small towns and prairie farms of the Midwest. The

other half were recently arrived immigrants, overwhelmingly from

Germany, who had settled in St. Louis and other urban centers along the

Mississippi River. No other Civil War army contained such a large

percentage of immigrants from a single ethnic group. The situation was

compounded by the presence of a high-ranking German-born officer:

Brigadier General Franz Sigel.

|

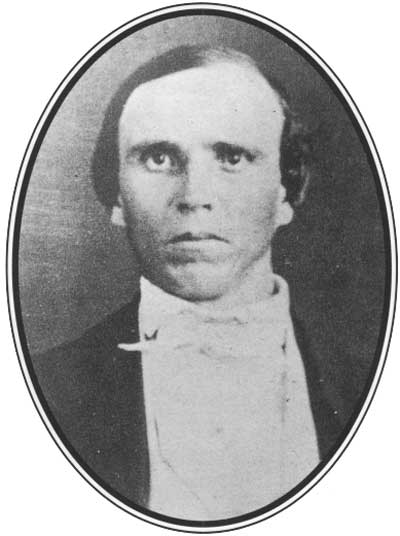

BRIGADIER GENERAL FRANZ SIGEL (USAMHI)

|

Sigel, 38, was a graduate of Karlsruhe military academy in Germany,

but his performance during the first year of the Civil War in Missouri

had been uneven. Despite being defeated at Carthage and routed at

Wilson's Creek, Sigel believed that he deserved to lead the next

offensive against Price. Outraged when Curtis was appointed over him,

Sigel resigned in a huff. This caused a political flap because Sigel, an

early master of public relations, had made himself into a symbol of

German commitment to the Union cause. He had a devoted following among

the large German population in Missouri and elsewhere in the country.

Consequently, Halleck convinced Sigel to withdraw his resignation and

return to the Army of the Southwest. Ambitious, erratic, and

unprincipled, but not without genuine military talent, Sigel would play

a curious role in the coming campaign.

Curtis went out of his way to avoid antagonizing Sigel and the

thousands of other German and central European immigrants under his

command. He divided his army into four undersized divisions loosely

based on ethnic lines. Brigadier General Alexander S. Asboth (a native

of Hungary) and Colonel Peter J. Osterhaus (a native of Germany)

commanded the two "German" divisions, while Colonel Eugene A. Carr and

Colonel Jefferson C. Davis, representing Illinois and Indiana

respectively, led the two "American" divisions. Curtis named Sigel

second in command of the army (a meaningless honorific) and gave him

nominal supervision of the two "German" divisions. Curtis came to regret

the latter decision, but at the beginning of the campaign he had no

reason to doubt Sigel's competence.

On January 13, 1862, after two weeks of preparations, Curtis set the

campaign in motion. For the next four weeks the Army of the Southwest

struggled across the Ozark Plateau toward Springfield. Inexperience and

inclement weather caused delays and sometimes brought the long blue

column to a complete stop. Heavy snowstorms were followed by springlike

thaws. A disgusted Union soldier described the resulting situation as

"mud without mercy." After only a few days on the march it was clear to

everyone why armies avoided winter campaigns. Nevertheless, Curtis and

his troops persevered. As the weeks passed the pace quickened and the

Yankees closed in on Springfield.

|

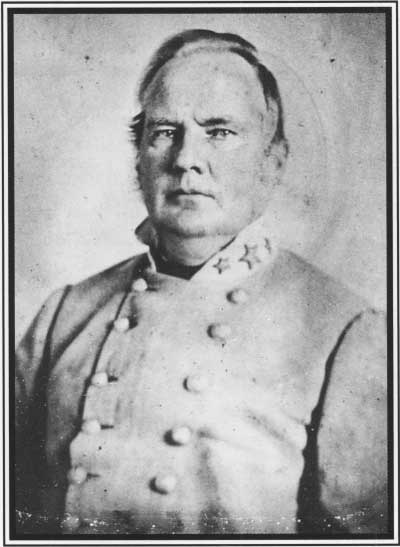

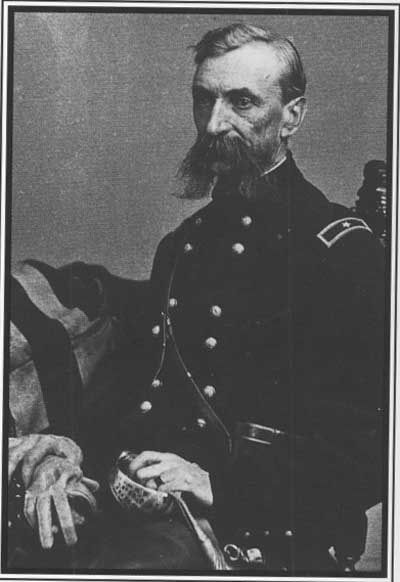

MAJOR GENERAL STERLING PRICE (TEXAS STATE LIBRARY & ARCHIVES

COMMISSION)

|

As Halleck had hoped, Price was entirely unprepared for the

appearance of a Union army in southwest Missouri in the middle of

winter. He had neglected to fortify Springfield, and he rightly feared

that the approaching army outnumbered his own. After dithering for

several critical days, Price swallowed his pride and called upon

McCulloch for assistance. But McCulloch had not yet returned from

Virginia, and McIntosh and Hebért were reluctant to take any important

action without his approval, especially when it involved Price and

Missouri. Price waited for McCulloch or a miracle until the last

possible moment, then abandoned Springfield without a fight and

retreated south. If McCulloch would not join him in Missouri, he would

join McCulloch in Arkansas.

Much to Price's surprise, Curtis followed. Unlike many other

generals at this early stage of the war, Curtis understood that his

primary objective was the neutralization of the opposing army, not the

occupation of territory. After taking permanent possession of

Springfield, he hurried after Price, determined to bring him to battle

at the first opportunity. The result was a rare instance of a sustained

pursuit of one army by another in the Civil War.

For four days the two columns tramped south along Telegraph Road, a

primitive frontier highway that connected all of the major towns in

southwest Missouri and northwest Arkansas. Sharp engagements flared

between the Confederate rear guard and the Union vanguard at Crane

Creek, Flat Creek, and Sugar Creek. The weather turned intensely cold,

and soldiers and animals in both armies endured snow, sleet, and

freezing rain. "I felt like I was dying, I was so chilled," recalled

Samuel McDaniel of the Missouri State Guard. "The snow was all over us,

and our clothes frozen on our bodies." As the grinding chase went on

through McDowell, Cassville, and Keetsville, the trail of Price's army

was marked by broken-down wagons, dead and dying horses and mules, and a

seemingly endless assortment of pots, desks, chairs, bedding, and

clothes. Hundreds of exhausted Rebels also were found along the

roadside. Curtis reported to Halleck that "more straggling prisoners are

being taken than I know what to do with."

Angry at being ignored and embarrassed at being ejected from

Missouri, Price allowed three critical days to pass before he informed

McIntosh and Hebért that he was headed in their direction with a Yankee

army on his heels. When a courier from Price finally arrived in

northwest Arkansas with the astounding news, Confederate cantonments

from Bentonville to Fort Smith exploded into frantic activity as

McCulloch's troops scrambled to prepare for a Union invasion.

The hard-pressed Missourians hurried across the state line into

Arkansas on February 16. No one realized it at the time, but when Price

led his soldiers out of Missouri the Confederacy suffered an

irreversible strategic defeat. Never again would a Confederate military

force return to Missouri with any intention or realistic chance of

staying. From that day forward, Missouri's star was effectively returned

to the United States flag.

|

THE BUTTERFIELD OVERLAND MAIL AND ELKHORN TAVERN

In 1858 Congress authorized the establishment of an overland mail

service between St. Louis and San Francisco. The $600,000 contract went

to John Butterfield, who established the short-lived but remarkable

operation that bears his name. For three years Butterfield Overland Mail

stagecoaches carried mail and passengers across some of the most

difficult and desolate territory on the continent. Shortly after

Butterfield began operations, a telegraph line was strung between

Springfield, Missouri, and Van Buren, Arkansas, giving the rugged Ozark

portion of the Overland Mail route its common name, Telegraph (or Wire)

Road. The Civil War brought an end to the Butterfield enterprise, but

not before it kindled the national imagination and spurred economic

growth on the southwest frontier.

Elkhorn Tavern was one of several well-known establishments along

Telegraph Road. The prominent two-story log structure, built around

1840, was located at a busy crossroads and served as a community center

of sorts. It was not an official Overland Mail station, but westbound

coaches often stopped at the tavern after the difficult ascent from

Cross Timber Hollow in order to rest the horses and allow drivers and

passengers to obtain food and beverages. But in spite of its name and

variegated functions, Elkhorn Tavern was primarily a residence, the home

of the Cox family, among the more prosperous inhabitants of the

hardscrabble highland area known as Pea Ridge.

Elkhorn Tavern was in the thick of the fighting on March 7-8, 1862.

Jesse Cox was away on business in Kansas selling cattle to the Union

army, but his wife, Polly, along with their three youngest sons and a

daughter-in-law, huddled in the cellar during the battle. The family

survived unscathed, but the tavern, outbuildings, and fences suffered

extensively. Confederate commanders Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price

spent the night of March 7 in the orchard in the north yard. The

building was filled with gravely wounded soldiers of both sides during

the battle and continued to serve as a hospital for weeks afterward.

Union forces returned to northwest Arkansas during the Prairie Grove

campaign in October 1862. The 1st Arkansas Cavalry (Union) was stationed

at Elkhorn Tavern to guard the Union supply line back to Springfield.

When the "Mountain Feds" departed early in 1863, local pro-Confederate

bushwhackers burned the building. The loss of their home was a heavy

blow to the Cox family, but Joseph Cox, son of Jesse and Polly, rebuilt

the tavern on the original foundations in 1865. It remained in the Cox

family until the establishment of Pea Ridge National Military Park in

1962.

|

THE SECOND OR POSTWAR TAVERN, BUILT ON THE ORIGINAL FOUNDATIONS, CLOSELY

RESEMBLED THE WARTIME STRUCTURE. (THE WESTERN HISTORY COLLECTION,

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA)

|

|

The next day, February 17, the Army of the Southwest followed. In

crossing the state line Curtis not only entered Arkansas, he also

invaded the Confederacy. Union bands played patriotic and popular tunes,

including, appropriately enough, "The Arkansas Traveler." Curtis

congratulated his cheering men for being the first Union soldiers to set

foot on the "virgin soil" of Arkansas. "Such yelling and whooping, it

was glorious," Major John C. Black of the 37th Illinois informed his

mother. Exhilarated by the unexpected success of his campaign, Curtis

sent a triumphant message to Halleck in St. Louis: "The flag of our

Union again floats in Arkansas."

|

CITY AND POST OF FORT SMITH, ARKANSAS (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

Forgotten in all the excitement was the fact that the purpose of the

Union operation was to enable Halleck to invade the Confederacy hundreds

of miles to the east. Neither Halleck nor Curtis had anticipated that a

limited campaign designed to neutralize Price would take the Union army

out of Missouri and into Arkansas. As sometimes happens with military

operations, Curtis's southward surge into Rebeldom had taken on a life

of its own.

Later that day, about five miles south of the Arkansas-Missouri state

line, Curtis and his men climbed a steep hill and marched past an

establishment named Elkhorn Tavern. The building was located on the

northern edge of a broad tableland known locally as Pea Ridge. Few if

any of the Union soldiers gave the place a second thought, though within

three weeks many of them would be fighting for their lives in the shadow

of the two-story hostelry.

About four miles south of Elkhorn Tavern, on the south side of Little

Sugar Creek, the horsemen in the van of the Union column encountered a

strong line of infantry, cavalry, and artillery blocking Telegraph Road.

For the first time since fleeing Springfield, the Rebels appeared to be

making a stand. The reason for the unexpected shift in tactics was not a

change of heart on Price's part, but the arrival of Confederate troops

from McCulloch's army under the command of Hebért. Hurrying north from

Cross Hollows, fresh Arkansas and Louisiana soldiers met the bedraggled

Missourians trudging south. At Price's request, Hébert deployed

his men across the road on James Dunagin's modest farm after the

Missourians had passed. He intended to halt or at least slow the

oncoming Union force in order to allow Price to reach Cross Hollows, a

dozen miles to the south.

|

MAJOR JOHN C. BLACK, 37TH ILLINOIS (ILLINOIS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

COLONEL LOUIS HÉBERT (LC)

|

Curtis was undeterred by the sight of the enemy line of battle and

sent his column rushing ahead. He expected the Rebels to follow their

usual pattern of making a brief stand and then resuming the retreat.

Curtis did not realize that he was facing a portion of McCulloch's army.

After an initial clash in which a Union cavalry thrust was repulsed, the

two sides blasted away at each other with artillery until sunset. The

Confederates withdrew in the gathering darkness just as Union infantry

began to arrive in force. The fight at Little Sugar Creek (or Dunagin's

farm) on February 17 was the first significant clash on Arkansas soil

and the first time McCulloch's troops had been in action since Wilson's

Creek six months earlier. It cost the lives of thirteen Union soldiers

and perhaps twenty-six Confederates.

After Little Sugar Creek, Price continued his headlong flight down

Telegraph Road to Cross Hollows, with Hebért bringing up the rear. Cross

Hollows was the principal Confederate cantonment in northwest Arkansas.

There, at last, Price's cold and weary soldiers joined the main body of

McCulloch's army.

Curtis did not pursue. He camped for two days in the valley of Little

Sugar Creek to allow his exhausted men and animals to rest and

recuperate. He studied the local terrain and took careful note of the

limestone bluffs that run along the north side of Little Sugar Creek

valley and form the southern edge of the Pea Ridge tableland. The bluffs

struck Curtis as an excellent defensive position should the Confederates

ever launch a counterattack against his isolated army.

While keeping Little Sugar Creek in mind as a potential defensive

bastion, Curtis nonetheless was determined to maintain the pressure on

Price and McCulloch. Excited local Unionists flocked to his camp and

provided him with information about roads and the Confederate cantonment

at Cross Hollows. Curtis decided not to advance directly toward Cross

Hollows on Telegraph Road but to swing around to the west by way of

Bentonville so as to compel Price and McCulloch to retreat or be cut

off.

|

ELKHORN TAVERN AS RESTORED BY THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE. THE BUILDING

FACES TELEGRAPH ROAD. (NPS PHOTO BY BOB NORRIS)

|

On February 18 Curtis sent Brigadier General Alexander S. Asboth on a

reconnaissance in force to Bentonville, southwest of Little Sugar

Creek. Asboth, 50, a former Hungarian officer, was the weakest of

Curtis's four division commanders, but he was brave and dashing and

proved to be a competent cavalry leader. When he reported that the

rolling terrain west of Cross Hollows was clear of enemy soldiers,

Curtis prepared to move his command in that direction.

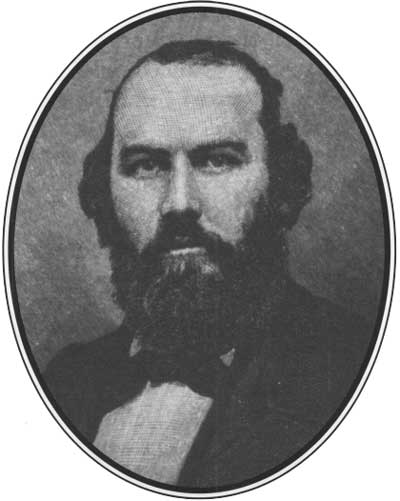

Curtis did not know that the Confederates already were abandoning

Cross Hollows. Returning from Virginia, McCulloch reached Cross Hollows

only a few hours after the fight at Little Sugar Creek. He received a

tumultuous welcome from his troops, who cheered and tossed their hats in

the air at the sight of their long-absent commander. As he passed each

regiment the laconic Texan said simply: "Men, I am glad to see you!"

When he reached his headquarters and conferred with McIntosh and

Hebért, McCulloch was shocked to learn of Price's headlong flight from

Missouri and the presence of a Union army on Arkansas soil, only a few

miles to the north at Little Sugar Creek. McCulloch had laid out the

cantonment at Cross Hollows, and he knew that the position was

untenable. It was a large, sheltered camp with plenty of wood and water,

but it was not a defensive strongpoint. The Yankees could simply

march around to the west of Cross Hollows and trap the Arkansas and

Missouri armies against the White River, which flowed past the east side

of the cantonment. (This was precisely what Curtis had in mind.) It was

obvious to McCulloch that the Confederates had to fall back deeper into

Arkansas in order to gain time and room to maneuver. Price, mercurial

and contrary as ever, would have none of it. After retreating for five

days, he inexplicably insisted on making a stand at Cross Hollows

despite the unfavorable ground. Most of his subordinates, however, sided

with McCulloch, Price finally capitulated.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL ALEXANDER S. ASBOTH (USAMHI)

|

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL JAMES McINTOSH (BL)

|

And so the retreat resumed on February 19. Confederate and Missouri

State Guard soldiers burned the complex of barracks, storehouses, and

mills in Cross Hollows and trudged south on Telegraph Road to Mudtown in

miserably cold weather. The next day they reached Fayetteville, the

principal town in northwest Arkansas. Fayetteville was a major supply

depot, but McCulloch had no way to remove the tons of food, ammunition,

and equipment stored in the town. Because Price had tumbled into

Arkansas without any warning, the Confederate supply system was

unprepared for the emergency. The army's teams and wagons were still

fifty miles to the south in the Arkansas River Valley.

McCulloch was unwilling to permit so much valuable material to fall

into enemy hands, so he made everything in Fayetteville available to the

troops. As the men marched through the center of town they were

permitted to break ranks and grab what they could. A soldier in the 2nd

Missouri named I. V. Smith noted that "nearly every man in the regiment

got a ham or a shoulder or a side of bacon, ran his bayonet through them

and carried it in to camp." He added that "it was a novel sight to see

so much meat on the march." Unfortunately, the disorganized method of

distribution quickly degenerated into looting and vandalism. Soldiers

rushed down side streets and ransacked homes, businesses, and even

churches. McCulloch made no effort to restore order. A disgusted

Confederate officer called the sack of Fayetteville "one of the most

disgraceful scenes that I ever saw."

The situation grew even worse the next day when McCulloch ordered all

remaining supplies in Fayetteville destroyed. Buildings filled with

combustibles, including tons of ammunition, were set afire with no

thought given to the consequences. The resulting explosions destroyed

several city blocks in the middle of town. As a result of McCulloch's

incendiary tendencies, Fayetteville gained the distinction of being one

of the first southern towns—but far from the last—to feel the

hard hand of war.

Burdened with food, clothing, jewelry, toys, and even furniture, the

Confederates staggered south another seventeen miles on Telegraph Road.

They finally halted near Strickler's Station in the Boston Mountains,

the rugged southern escarpment of the Ozark Plateau. McCulloch's army

camped along Telegraph Road; Price's army bivouacked just to the west

along Cove Creek Road. The long retreat from Springfield that had begun

ten days and 120 miles earlier was over.

|

FAYETTEVILLE, ARKANSAS (BL)

|

Word soon reached Curtis that the Confederates had abandoned Cross

Hollows and Fayetteville and fallen back into the Boston Mountains.

Curtis paused to consider the strategic situation. He now faced the two

largest Confederate armies west of the Mississippi River, the same

combined force that had overwhelmed Lyon at Wilson's Creek six months

earlier. Curtis correctly concluded that the Rebels outnumbered his own

small command by a substantial margin. Indeed, the Army of the Southwest

was not only small, it was getting smaller. Attrition caused by hard

marching and the need to garrison Springfield and other vital points

along the long line of communication stretching all the way back to

Rolla had cost the Union army nearly one-fifth of its original manpower.

Curtis had slightly more than 10,000 men under his immediate

command in Arkansas. Moreover, he was over two hundred miles south of

the railhead at Rolla and, despite Quartermaster Sheridan's best

efforts, his supply situation was critical. Foraging was relatively

unproductive because northwest Arkansas had been drained of foodstuffs

by the Confederates for nearly a year. "It looks like starving if we do

not save rations," ominously noted Surgeon George Gordon of the 18th

Indiana.

After mulling over his other options, Curtis decided that he could

best shield Missouri by holding his position in northwest Arkansas. He

dispatched cavalry raids in various directions to gather information and

keep the Confederates off balance. The largest of these operations,

another reconnaissance in force led by Asboth, occupied what was left of

Fayetteville on February 22-26. Despite the presence of Unionist

citizens who hailed Asboth as a deliverer, Curtis concluded that he

could not hold Fayetteville because it was too close to the Rebel armies

lurking a few miles away in the Boston Mountains.

To facilitate foraging as much as possible, Curtis took a calculated

risk and divided his forces. He stationed his two "American" divisions

in Cross Hollows under his personal command and placed the two "German"

divisions under Sigel's command along McKissick's Creek, a short

distance west of Bentonville. Despite this demonstration of trust in his

second in command, Curtis was having serious doubts about Sigel's

capacity for high command. During the pursuit from Springfield Sigel's

behavior ranged from insubordinate to inexplicable. Unable to remove or

demote his principal subordinate for fear of triggering another

political uproar, Curtis had little choice but to continue to allow him

a certain amount of autonomy and hope for the best.

|

CAPTAIN PHILIP H. SHERIDAN, QUARTERMASTER OF THE ARMY OF THE SOUTHWEST.

(LC)

|

Curtis scattered smaller outposts across the countryside to monitor

enemy activities. Cross Hollows and McKissick's Creek were about fifteen

miles apart, and each was about a dozen miles from Little Sugar Creek.

If the Confederates came storming out of the Boston Mountains, Curtis

planned for the Army of the Southwest to reunite atop the limestone

bluffs at Little Sugar Creek and make a defensive stand.

Despite his isolated position and his precarious logistical

situation, Curtis was determined to stand firm in Arkansas and prevent

Price from returning to his old mischief in Missouri. He telegraphed

Halleck: "Shall be on the alert, holding as securely as possible." What

happened next would be up to the Confederates.

Van Dorn was at his headquarters in Pocahontas when he learned of

Price's flight from Springfield and the disastrous series of events that

followed. He abandoned his plans for an invasion of Missouri from

northeast Arkansas and set out immediately on an nine-day journey across

central Arkansas to take personal command of the two Confederate armies

in the Boston Mountains. Along the way he fell into an icy river and

became ill. When he finally reached Van Buren in an ambulance—a

less than dashing form of transportation for a cavalryman—he was

handed a telegram from McCulloch at Strickler's Station. "I have ordered

the command to be ready to march as soon as you arrive," wrote the

Texan. "We await your arrival anxiously. We now have force enough to

whip the enemy." Van Dorn responded in the same vein: "I thank you for

anticipating me in regard to getting in readiness to move forward. We

must do it without delay." In addition to suffering from a fever, Van

Dorn now was burning with anticipation as well.

|

|