|

While McCulloch's division unraveled during the afternoon of March 7

at Leetown, a larger engagement raged two miles to the east in the

vicinity of Elkhorn Tavern. Earlier that morning, as noted above, Curtis

had learned that two Confederate forces of undetermined size were in his

rear. He had launched two spoiling attacks, one of which was commanded

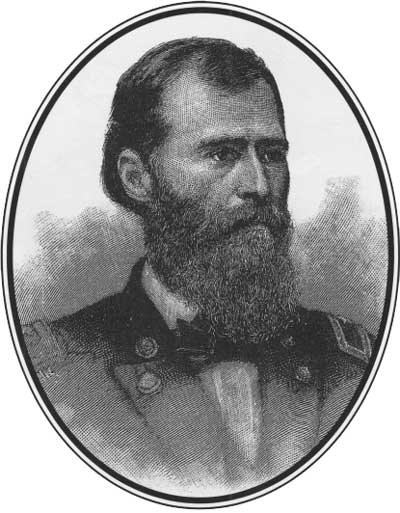

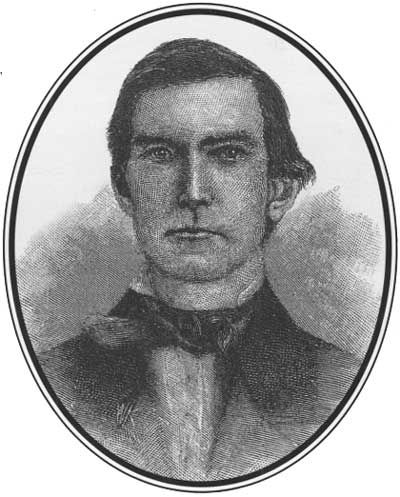

by Osterhaus. The other was led by Colonel Eugene A. Carr, 31, a West

Point graduate and a regular army officer. During a decade of frontier

service against the Comanches in Texas, Carr had earned a reputation as

an argumentative subordinate and a pugnacious fighter who did not know

when to quit.

Curtis instructed Carr to intercept the enemy force on Telegraph Road

in Cross Timber Hollow. He sent Carr on his way with the optimistic

prediction that he would "clean out that hollow in a very short time."

Carr hurried north on Telegraph Road along the east side of Big Mountain

with half of his division. Around noon he reached Elkhorn Tavern and

deployed Colonel Grenville M. Dodge's brigade to the right of the road

along the northern escarpment of Pea Ridge. The brigade consisted of the

4th Iowa, 35th Illinois, 3rd Illinois Cavalry, and the 1st Iowa Battery,

a total of about 1,400 men. At the tavern Carr found the battalion-sized

24th Missouri, which had been guarding the army's rear, and incorporated

it into his command. The thin Union line looked down into Cross Timber

Hollow, a deep gorge just north of the tavern. It was an immensely

strong position and Carr decided that instead of attempting to "clean

out" the hollow, he would wait for the Rebels to come to him.

He did not have long to wait. Price's division, personally led by Van

Dorn, approached from the north on Telegraph Road. The division had been

reduced by straggling and numbered only about 5,000 men, but it included

ten artillery batteries. Shortly before noon the weary Confederates

reached the steep slope that leads from the floor of Cross Timber Hollow

to the top of Pea Ridge. Fighting erupted unexpectedly when the leading

Rebels ran into a Union skirmish line near a tanyard at the foot of the

slope. Van Dorn, like McCulloch two miles to the west on Foster's farm,

was surprised to encounter enemy troops so far north of Little Sugar

Creek. Up to that moment he believed that his night march on Bentonville

Detour had gone undetected and that the Yankees were still in their

fortifications facing south.

The Confederate position deep in Cross Timber Hollow was like being

at the bottom of a well. Van Dorn could not see what was happening atop

Pea Ridge, three hundred feet above his head. At this critical moment

Van Dorn apparently became unnerved by his blindness and the unexpected

presence of Yankee skirmishers. He made a fateful decision. Instead of

continuing to hurry toward Elkhorn Tavern and the rendezvous with

McCulloch's division Van Dorn directed Price to halt, deploy his

division in line of battle at the foot of the slope, and "move forward

carefully." It probably was the most uncharacteristic order Van Dorn

ever issued.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

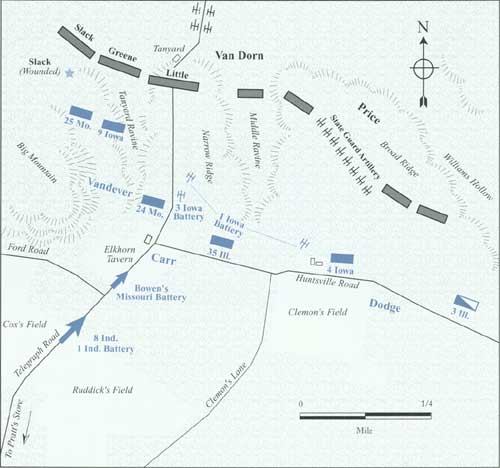

UNION FORCES HOLD ELKHORN TAVERN, LATE MORNING TO MIDAFTERNOON, MARCH 7, 1862

For most of March 7, the fighting around Elkhorn Tavern remained

fairly static. As reinforcements arrived from the Little Sugar Creek

fortifications, Carr strengthened and lengthened his line and launched

spoiling attacks down the slope. Van Dorn waited for McCulloch to arrive

on Ford Road and drive Carr away. He did not know that McCulloch was

engaged at Leetown.

|

For three days Van Dorn had been obsessed with speed at the expense

of all other considerations. Now, at the very moment when speed was of

vital importance, he emphasized caution in his directive to Price. The

only plausible explanation for this shift in mental gears is Van Dorn's

physical and mental condition. He was still unwell and, like all the

senior Confederate officers, he was worn out. McCulloch and McIntosh

were guilty of fatal lapses in judgment at about the same time, and

Hebért wandered away from his men in a daze. Perhaps the Confederate

high command at Pea Ridge on March 7 was too tired to think

straight.

The Missourians slowly formed a long, irregular line of battle across

a series of steep ridges and narrow valleys, Confederate soldiers on the

right, Missouri State Guard troops on the left. When all was ready,

Price sent his men up the slope. The woebegone Missourians had not

encountered so steep an incline since leaving the Boston Mountains three

days earlier, and they trudged uphill at a snail's pace, steadily

pushing back the screen of Union skirmishers.

|

COLONEL EUGENE A. CARR (BL)

|

While the Confederates deployed near the tanyard at the bottom of the

slope, Carr completed the arrangement of his forces at the top around

Elkhorn Tavern. Unlike Van Dorn, Carr had a fairly good view of what his

opponent was up to. Carr became alarmed as he watched the Confederate

line of battle unfold, for he had not expected to meet such a powerful

enemy force. It was apparent that he was badly outnumbered.

Nevertheless, Carr saw the situation in much the same way as did

Osterhaus at Leetown. The Union army's vast assemblage of supply wagons

was parked only a few hundred yards south of the tavern. Despite the

formidable odds, his only option was to stand and fight. To gain as much

time as possible, Carr decided to pitch into the Rebels and attempt to

throw them into confusion. He sent a plea for reinforcements to Curtis,

then got down to business.

Just as the Missourians began to move uphill, Carr personally led the

1st Iowa Battery about three hundred yards down Telegraph Road into

Cross Timber Hollow. When the Union guns opened fire, the astonished

Confederates stopped in their tracks. Missouri gunner Hunt P. Wilson was

impressed by the Union gunners, whom he described as "pouring in a

well-directed fire, knocking off limbs of trees and tearing up the

ground in fine style." But as more and more Confederate batteries joined

the fight, the tide turned. Carr reported that a "perfect storm" of

solid shot, case shot, grape shot, shell, splinters, and rocks rained

down on the outnumbered and outgunned Iowans. Men and horses were

struck down, caissons exploded, and guns were disabled, but the Iowans

grimly held their ground. "Give them hell boys," Carr shouted above the

din of battle. "Don't let them have it all their own way, give them

hell."

|

CAPTAIN JOSEPH SHELBY LED A COMPANY OF MISSOURI CAVALRY AT PEA RIDGE.

(STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI)

|

|

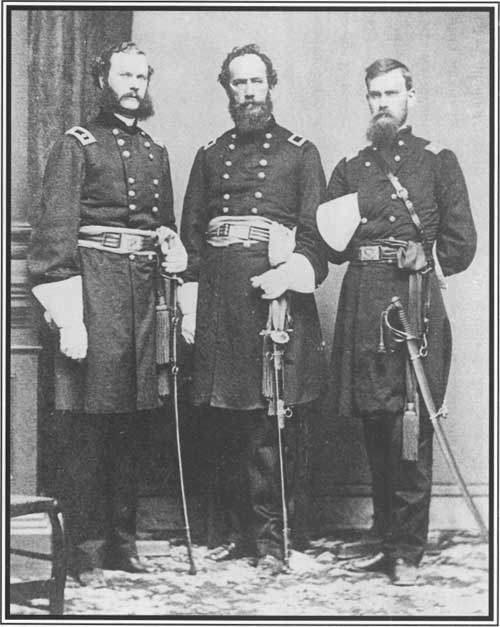

LEFT TO RIGHT, FRANCIS J. HERRON, WILLIAM VANDEVER, AND WILLIAM H. COYLE

(STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF IOWA)

|

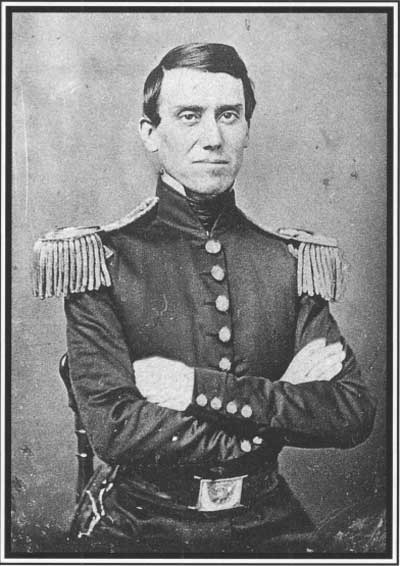

For much of the fight to come, Carr remained near his advanced

artillery position, cheering his men on and trying to get a sense of

what the Confederates were doing. It was, of course, a completely

inappropriate place for a division commander to be in the midst of a

battle, but Carr's heroic performance in Cross Timber Hollow earned him

three wounds, a promotion to brigadier general, the Medal of Honor, and

the undying respect of his men. More important, his efforts and those of

his Iowa artillerymen immobilized Price's division for two critical

hours.

Van Dorn was puzzled by Carr's aggressive tactics and directed Price

to halt his forward movement and assume a defensive position near the

bottom of Cross Timber Hollow. Possibly Van Dorn expected McCulloch's

division to arrive at any moment on Ford Road and drive the Union force

away from Elkhorn Tavern. In the meantime he was uncharacteristically

content to allow Price to exchange artillery fire with the Yankees. In

so doing, Van Dorn played directly into Carr's hands. Van Dorn's

decision to wait in Cross Timber Hollow was understandable, but it

proved to be a critical error, for it gave Curtis time to rush the rest of

Carr's division to Elkhorn Tavern.

During the afternoon Carr's thin ranks were bolstered by the arrival

of urgently needed reinforcements. After receiving Carr's plea for help,

Curtis ordered Colonel William Vandever at Little Sugar Creek to take

his brigade and hurry north. Vandever brought the 9th Iowa and 25th

Missouri—another 1,000 soldiers—and the 3rd Iowa Battery into

the growing fight around two o'clock. Shortly afterward two more guns

rumbled up to the tavern, escorted by a Missouri cavalry company

commanded by Captain Frederick W. Benteen of later Little Big Horn fame.

An hour later a battalion of the 8th Indiana and a section of the 1st

Indiana Battery arrived from Little Sugar Creek.

Now outnumbered only about two to one, Carr became even more

aggressive. He called the 3rd Iowa Battery down the slope to join what

was left of the 1st Iowa Battery, then he directed Dodge and Vandever to

launch spoiling attacks. The Union infantry and cavalry made repeated

lunges into Cross Timber Hollow, Dodge's regiments on the east side of

Telegraph Road, Vandever's on the west. They drove in Confederate

skirmishers, exchanged volleys with Price's main line of battle, then

retired to their original positions at the top of the slope. Every

downhill Union thrust, no matter how light, seemed to fix the

Confederates ever more firmly in place at the bottom of the slope.

|

COLONEL WILLIAM Y. SLACK (BL)

|

The artillery duel filled Cross Timber Hollow with smoke, and

soldiers of both sides blundered about in the haze. "The smoke from the

guns settled like a cloud upon the field," wrote an observer. "As the

day advanced this cloud grew more and more dense, and long before

nightfall the contending masses of infantry were unable to discern each

other, except at very short range." During one murky clash west of

Telegraph Road, Colonel William Y. Slack, commanding the 2nd Missouri

Brigade, joined his skirmishers to see what was happening and was

mortally wounded. Command of the brigade passed to Colonel Thomas H.

Rosser. A short time later Price was struck in the arm by a bullet. He

stayed on the field, but his effectiveness was much reduced.

Around midafternoon Van Dorn finally learned that McCulloch's

division was bogged down in an unexpected encounter at Leetown. He now

realized that he would have to fight his way out of Cross Timber Hollow

on his own. Shaking off his lethargy, Van Dorn directed Price to extend

his flanks as far as possible and envelop the shorter Union line. This

was no easy task given the difficult terrain and limited visibility in

the hollow, but around four o'clock Missouri State Guard troops reached

the top of Pea Ridge a mile east of Elkhorn Tavern, well beyond Carr's

right flank. Meanwhile, Rosser's 2nd Missouri Brigade and Colonel Colton

Greene's 3rd Missouri Brigade worked their way past Carr's left flank,

though they did not succeed in getting out of the hollow. Carr

inadvertently made things easier for the Rebels by drawing in his

extended flanks and forming a more compact line centered on Telegraph

Road.

Van Dorn could wait no longer. He ordered a general assault. The

Confederate left wing would roll up the Union right flank atop Pea

Ridge, while the Confederate center and right wing would push directly

up the slope and overpower the Yankees near the tavern. Because of the

length of the extended Confederate formation, a temporary change in

command arrangements was instituted. Price would personally command the

left wing despite his wound, Colonel Henry Little, the highly capable

commander of the 1st Missouri Brigade, would oversee the right wing. Van

Dorn would stay near Telegraph Road and provide Little with whatever

direction he might require.

There was barely an hour of daylight remaining when the Confederate

attack finally got under way. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Missouri Brigades,

supported by a variety of State Guard units, surged forward on either

side of Telegraph Road. They started off well enough, but fatigue,

foliage, and terrain quickly played havoc with military precision. The

formations gradually broke into smaller and smaller parts, with each

regiment, battalion, or even company advancing uphill at its own pace

and on its own course. The opposing forces were barely one hundred yards

apart when the Rebels emerged from the haze in the hollow and came into

full view of the Yankees clustered around Elkhorn Tavern.

|

COLONEL LEWIS HENRY LITTLE (CHICAGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

Volleys rippled along the edge of the Pea Ridge plateau as one Union

regiment after another opened fire. A Confederate officer declared that

the musketry "was extremely heavy and surpassed in severity anything our

men had as yet experienced."

|

Volleys rippled along the edge of the Pea Ridge plateau as one Union

regiment after another opened fire. A Confederate officer declared that

the musketry "was extremely heavy and surpassed in severity anything our

men had as yet experienced." Asa Payne of the 3rd Missouri recalled

these few minutes in vivid detail. "The Federal line was in full view

and I could hear something going zip, zip all around and could see the

dust flying out of the trees and the limbs and twigs seemed to be in a

commotion from the concussion of the guns." Fighting raged at extremely

close range for thirty minutes, and hundreds of men went down on both

sides, many with multiple wounds.

The Union defenders around Elkhorn Tavern fought from behind whatever

cover was available. "Each man sought a tree, a stump or a rock, loaded

and fired as rapidly as he could," recalled Nathan Harwood of the 9th

Iowa. Alonzo Abernethy of the same regiment felt that the battle for

possession of the tavern "raged with a fury which exceeded our worst

apprehensions." After an initial surge that carried them several hundred

yards uphill, the Confederate attackers faltered just short of the

crest. Staggered by the hail of bullets and canister, some Missouri

regiments even lost ground. For a few moments it appeared that Carr's

troops, despite their inferiority in numbers, might hold their

position.

Then, a quarter-mile west of Elkhorn Tavern, the Union left flank

crumpled under the pressure of Rosser's 2nd Missouri Brigade. Vandever

attempted to shift troops to meet this new threat, but his brigade,

already hard pressed by the host of Confederates to the north in Cross

Timber Hollow, was overwhelmed, "It seemed to me that the whole world

over there was full of rebels," said an unnerved Union officer of the

level ground behind Elkhorn Tavern. Carr's position on the west side of

Telegraph Road began to give way.

Down in Cross Timber Hollow, Little sensed that the Yankees around

the tavern were breaking. He called upon the soldiers of his own 1st

Missouri Brigade and Greene's 3rd Missouri Brigade to reform their ranks

and make one last charge. Some of the Rebels barely had the strength to

plod up the slope in slow motion; others somehow managed both a trot and

a blood-curdling cheer. Nathan S. Harwood of the 9th Iowa watched the

Rebels approach "with a yell and a fury that had a tendency to make each

hair on one's head to stand on its particular end."

Threatened in front and flank, the Union regiments clustered around

Elkhorn Tavern fell back through a maze of fences and outbuildings. The

thin blue line that had held the high ground for so many hours was

broken beyond repair. Now the only Union presence north of the tavern

was a hodgepodge of guns from different batteries arrayed in a

semicircle on Telegraph Road. After their supporting infantry streamed

to the rear, the guns were vulnerable.

|

THE 2ND MISSOURI FINALLY OVERRUNS UNION ARTILLERY NEAR ELKHORN TAVERN

LATE ON THE AFTERNOON OF MARCH 7. THE SOLDIERS WORE WHITISH UNIFORMS OF

UNDYED WOOL RECENTLY ISSUED TO THEM IN THE BOSTON MOUNTAINS. (PAINTING

BY ANDY THOMAS COURTESY OF MAZE CREEK STUDIO)

|

Colonel John Q. Burbridge of the 2nd Missouri saw his chance. "On to

the battery!" he shouted, and led his men directly up Telegraph Road

toward the Union guns. Some artillerymen fled, but most worked

frantically to limber up their weapons and escape. A few carried out a

final act of defiance and fired a ragged salvo of canister into the

faces of the oncoming Rebels. Dozens of Missourians were mowed down by

the hurricane of metal, and dozens more were knocked senseless by the

concussion. The surviving Rebels stumbled forward and captured two of

the smoking guns, but it was a hollow victory. The Union artillerymen

took advantage of the chaos and rolled down Telegraph Road to safety

with most of their guns and caissons.

In the midst of this chaotic scene, Lieutenant Colonel Francis J.

Herron of the 9th Iowa, described by a fellow officer as "too brave for

his own good," reformed his regiment in a field just south of Elkhorn

Tavern. For a few critical minutes the Iowans put up a desperate rear

guard defense that allowed other Union regiments to get away in

reasonably good order and threw the Confederates swarming around the

tavern into an even greater state of confusion. Then two guns of Captain

Henry Guibor's Missouri Battery emerged from the depths of Cross Timber

Hollow and went into action in front of the tavern. The gunners sprayed

the 9th Iowa with grapeshot. Herron was wounded and captured when his

stricken horse fell on him, and the Iowans were forced to resume their

retreat. Herron's exploits earned him a promotion to brigadier general

and a Medal of Honor.

|

|