|

The eight-mile march on Bentonville Detour during the night of March

6 was a terrible experience for the Army of the West. The snow had

stopped, but the temperature was even colder than the night before. The

shivering column shuffled along at a snail's pace, delayed for hours by

confusion, weariness, and frigid streams. Then, just past Twelve Corner

Church, the Confederates reached the first barricade of trees that

Dodge's woodcutters had felled only a few hours earlier. The column

halted as the Missourians in the van struggled to clear the road with

only a handful of axes. After two hours the advance began again, only to

encounter a second tangle of trees before dawn. Another halt and another

two hours lost.

Van Dorn's numerical superiority continued to erode as men dropped

out of the ranks in droves. "Every half mile I saw the Infantry in

squads of fifty and sixty, and even more lieing on the roadside, asleep,

and overcome with hunger and fatigue," wrote Major Lawrence S. Ross of

the 6th Texas Cavalry. Other Confederate officers reported that up to

one-third of their men fell by the wayside during the seemingly endless

night march. At dawn on March 7, the shrinking Army of the West was

strung out for eight miles. Price's division had reached Telegraph Road,

but Pike's tiny Indian brigade at the tail of the column was still in

Little Sugar Creek valley.

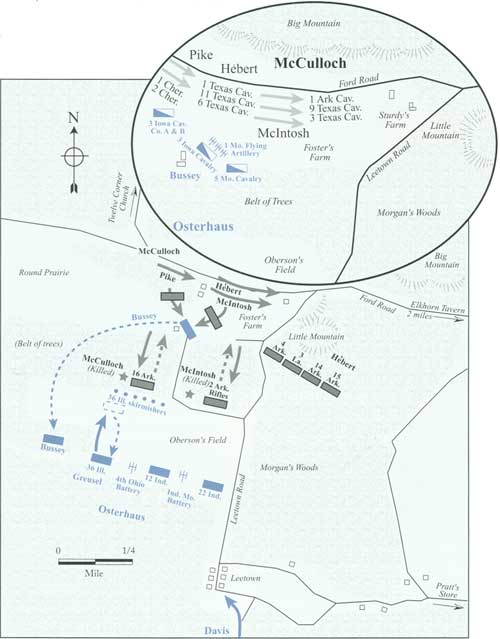

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

VAN DORN ENCIRCLES CURTIS, NIGHT MARCH 6 TO MORNING, MARCH 7, 1862

During the night of March 6-7, Van Dorn marched around

Curtis's right flank on the Bentonville Detour. The next morning, Van

Dorn and Price turned south on Telegraph Road. McCulloch and Pike

branched off at Twelve Corner Church and moved east on Ford Road. Curtis

sent Osterhaus and Carr to block the Confederates. Most of the Union

army remained in the Little Sugar Creek fortifications.

|

Despite the loss of manpower and the even more critical loss of time,

Van Dorn was elated at the apparent success of his last-minute maneuver

to envelop Curtis. He had achieved what every commander dreamed about:

his army was squarely across the enemy's line of communications. Still

not fully recovered from his illness, Van Dorn emerged from his

ambulance, swaddled in heavy clothing, and mounted his horse. It was the

supreme moment of his career.

Though a victory of Napoleonic proportions seemed to be at hand, Van

Dorn was concerned about the attenuated disposition of the Army of the

West. It would be midafternoon before the trailing portion of the long,

long column reached Telegraph Road and late afternoon before it arrived

at Elkhorn Tavern. Casting about for some way to hasten the

concentration of his forces, Van Dorn learned of a lane called Ford Road

that connected Bentonville Detour at Twelve Corner Church with Telegraph

Road near Elkhorn Tavern. He now made a decision that seemed sound but

was to prove controversial and costly.

|

THE SANDSTONE PROMONTORY ATOP BIG MOUNTAIN PROVIDES A SUPERB VIEW OF THE

ROLLING PEA RIDGE PLATEAU. THE VIEW IS TO THE SOUTHWEST WITH LITTLE

MOUNTAIN VISIBLE ON THE FAR RIGHT. (NPS PHOTO BY BOB NORRIS)

|

Price's division, as planned, would proceed south on Telegraph Road

around the east side of a rugged, wooded ridge called Big Mountain.

McCulloch's division and Pike's brigade, several miles back on

Bentonville Detour, would turn south onto Ford Road and march around the

west and south sides of Big Mountain. The Ford Road shortcut would save

the Confederates both miles and hours. If all went well, the two halves

of the Army of the West would reunite around midday near Elkhorn Tavern

atop the rolling expanse of Pea Ridge. There the Confederates would

deploy for battle and advance upon the unsuspecting Federals with plenty

of daylight remaining. Van Dorn had no qualms about dividing his army

in the presence of the enemy because he believed the Union army was

still occupying the fortifications at Little Sugar Creek, expecting an

attack from the south.

That was not the case, Union patrols detected the Confederate

movement before dawn on March 7. Curtis received reports of enemy forces

on Bentonville Detour near Twelve Corner Church and on Telegraph Road

north of Elkhorn Tavern. Curtis was taken aback by the reports. He had

expected Van Dorn to spend some time probing the Little Sugar Creek

fortifications before making any offensive moves. Methodical by nature,

Curtis had difficulty grasping the bold, even reckless, mentality of his

opponent. He incorrectly concluded that the presence of Confederate

troops to the north was a diversion and that the primary threat still

lay to the south along Little Sugar Creek.

Nevertheless, Curtis could not permit even a diversionary enemy force

to rampage around in his rear. The broad fields south of Elkhorn

Tavern, about two miles north of the Union fortifications, were crowded

with hundreds of irreplaceable supply wagons, the vital link between the

Army of the Southwest and the railhead at Rolla. Curtis decided to keep

about two thirds of his army at Little Sugar Creek and send the other

one-third north to intercept the approaching Confederate columns and

keep them away from his trains.

Around midmorning on March 7, Curtis directed Colonel Peter J.

Osterhaus to withdraw one brigade of his division from the Little Sugar

Creek fortifications and head toward the Confederate force reported to

be near Twelve Corner Church. A steady and reliable officer, Osterhaus,

39, was a good choice for such an independent assignment. Osterhaus

unknowingly was seeking McCulloch's column, which had turned off

Bentonville Detour at Twelve Corner Church and was moving around the

west side of Big Mountain on Ford Road. Osterhaus rode ahead of his

infantry in order to familiarize himself with the countryside atop Pea

Ridge. He was accompanied by Colonel Cyrus Bussey and a small cavalry

force. Bussey's command consisted of detachments from the 1st, 4th, and

5th Missouri Cavalry and the 3rd Iowa Cavalry—perhaps six hundred

men—and three guns from the 1st Missouri Flying Artillery.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE BATTLE OF LEETOWN BEGINS, LATE MORNING MARCH 7, 1862

As McCulloch marched east on Ford Road,

Osterhaus approached from the south and attacked. McIntosh and Pike

counterattacked and routed Bussey's small cavalry force on Foster's

Farm, but Osterhaus's main line in Oberson's Field held fast. McCulloch

and Mcintosh were killed in the belt of trees, throwing the Confederates

into disarray. Meanwhile, Davis arrived from Little Sugar Creek.

|

Around one o'clock the Union advance party clattered through the

hamlet of Leetown, passed by Samuel Oberson's large cornfield, and

entered a belt of trees. When Osterhaus emerged from the trees onto

Wiley Foster's farm, he came to an abrupt halt. Directly in front of him

was McCulloch's entire division advancing in a massive formation six

regiments wide with flags flying and weapons gleaming in the midday sun.

The Confederates had turned the corner of Big Mountain and were plodding

eastward on and alongside Ford Road.

Osterhaus was shocked by the sight of so many Rebels. This was not

the modest-sized diversionary force he had expected to encounter. It

appeared that he had stumbled upon half of the Confederate army! Then he

realized that the massive enemy formation was heading directly toward

the Union army's trains near Elkhorn Tavern, only two miles to the east.

"Notwithstanding my command was entirely inadequate to the overwhelming

masses opposed to me," he reported without exaggeration, "I could not

hesitate in my course of action." Osterhaus directed Bussey to unlimber

his three guns and fire on the tightly packed Confederate formation. The

opening shots of the fight at Leetown struck down dozens of Rebel

cavalrymen.

|

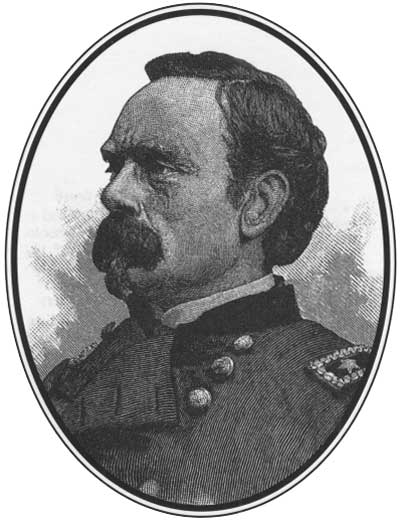

COLONEL PETER J. OSTERHAUS (BL)

|

Now it was McCulloch's turn to be surprised. Like Van Dorn, he

believed the Union forces were still in their fortifications at Little

Sugar Creek awaiting an attack from the south. He was looking forward,

both literally and figuratively, to meeting Van Dorn and Price at

Elkhorn Tavern, which lay directly ahead. The last thing he expected was

an attack from his right rear.

After a few minutes of confusion in the Confederate ranks, McCulloch

sent McIntosh and his 3,000 cavalrymen sweeping across Foster's wheat

field toward Osterhaus's position in one of the Civil War's most

colorful cavalry charges. Shrieking the Comanche war whoop and

brandishing carbines, shotguns, pistols, sabers, Bowie knives, and

hatchets, troopers of the 6th, 9th, and 11th Texas Cavalry, 1st Texas

Cavalry Battalion, and 1st Arkansas Cavalry Battalion overwhelmed the

small Union advance party. "In every direction I could see my comrades

falling," recalled Henry Dysart of the 3rd Iowa Cavalry. "Horses

frencied and riderless, ran to and fro. Men and horses ran in collision

crushing each other to the ground. Dismounted troopers ran in every

direction. Officers tried to rally their men but order gave way to

confusion. The scene baffles description." The Confederates scattered

the Union cavalry and captured the three guns.

|

MCINTOSH'S CAVALRY BRIGADE SWEPT ACROSS WILEY FOSTER'S FIELDS TOWARD THE

BELT OF TREES IN THE BACKGROUND TO OPEN THE FIGHTING AT LEETOWN. THE

CONFEDERATES OVERWHELMED BUSSEY'S SMALL UNION DETACHMENT, WHICH WAS

DEPLOYED NEAR THE RIGHT EDGE OF THIS PHOTOGRAPH. (NPS PHOTO BY BOB

NORRIS)

|

A few hundred yards to the west, Pike conformed to McIntosh's

movements by ordering his Indians to attack as well. The 1st and 2nd

Cherokee Mounted Rifles, some on horseback, others on foot, picked their

way through a patch of woods and drove off two isolated companies of the

3rd Iowa Cavalry. Because of a popular but wildly inaccurate Currier and

Ives print, there is a persistent myth that the Cherokees took part in

McIntosh's massed cavalry charge and that they were dressed in war

bonnets and other inappropriate Plains Indian regalia. In fact, the

Indians fought on their own in the woods bordering the west side of

Foster's farm. Some sported colorful turbans and other items of

traditional Cherokee war dress, but for the most part they wore the same

mix of store-bought and homespun clothing as did practically every other

southerner in the Army of the West. (Only the men of the 3rd Louisiana

and 1st Missouri Brigade had uniforms.) The modest Cherokee contribution

to the Confederate effort at Pea Ridge was tarnished when a handful of

Indians murdered, scalped, and mutilated eight fallen Iowa soldiers.

Immensely relieved, Osterhaus informed Curtis that Greusel's

troops "had stood without flinching" despite the temptation to flee. It

was a critical moment in the developing battle. Instead of an easy

victory, McCulloch would have a fight on his hands.

|

Survivors of the Union advance party fell back through the belt of

trees and raced across Oberson's cornfield. The Yankee cavalrymen

thundered past Colonel Nicholas Greusel's infantry brigade which was

just entering the field. "It was one of the most wild and exciting

scenes that I have ever beheld," recalled Charles B. Stiles of the 36th

Illinois. As the horsemen sped past the gaping infantrymen some of them

shouted: "Turn back! Turn back! They'll give you hell!"

For a moment the blue ranks wavered, then Greusel shouted: "Officers

and men, you have it in your power to make or prevent another Bull Run

affair. I want every man to stand to his post." The reference to the

shameful debacle outside Washington only seven months earlier did the

trick. The rattled infantrymen settled down and resumed their

deployment. When Osterhaus arrived a few moments later he found Greusel

calmly supervising the formation of a line of battle on the south side

of Oberson's field. Immensely relieved, Osterhaus informed Curtis that

Greusel's troops "had stood without flinching" despite the temptation to

flee. It was a critical moment in the developing battle. Instead of an

easy victory, McCulloch would have a fight on his hands.

Osterhaus sent a message to Curtis stating that he had engaged a

large enemy force north of Leetown and urgently needed reinforcements.

At this stage of the battle the Union force at Leetown consisted of only

the 36th Illinois, 12th Missouri, and 22nd Indiana—fewer than 1,600

men—supported by the 4th Ohio Battery and the Independent Missouri

Battery. Bussey's cavalrymen were in such disarray that they would not

be of much help for some time. McCulloch's powerful force had been

weakened by straggling but probably still consisted of about 7,000 men

and four batteries of artillery, more than enough to sweep aside the

Union command if properly handled. Osterhaus had no illusions about his

ability to repel a full-scale attack. His only hope was to hold out

until reinforcements arrived.

|

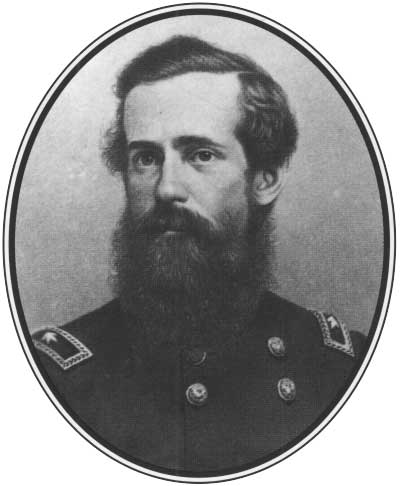

COLONEL CYRUS BUSSEY (USAMHI)

|

Greusel was equally anxious. Casting about for some way to buy time,

he ordered his artillery to fire in the general direction of the enemy.

Though the Confederates were out of sight on the north side of the belt

of trees that separated the Foster and Oberson farms, Greusel hoped a

rain of shells would cause disorder in the Confederate ranks and

interrupt preparations for an assault.

Though Greusel did not know it, the Confederate ranks were in

considerable disorder even before he gave his gunners permission to open

fire. Thousands of exhilarated Rebel cavalrymen milled around on

Foster's farm, gawking at dead and wounded Yankees and telling each

other of their exploits during the charge. The bedlam worsened when

hundreds of Cherokees rushed up and joined the celebration around the

three captured guns. According to one amazed Confederate officer, "the

Indians swarmed around the guns like bees, in great confusion, jabbering

and yelling at a furious rate." Pike reported that the Cherokees were

"in the utmost confusion, all talking, riding this way and that, and

listening to no orders from anyone," including him. Annoyed at the

breakdown of discipline, McCulloch went to work to restore order and

reform his mounted units.

|

NO PHOTOGRAPHER OR ARTIST WAS PRESENT AT PEA RIDGE, SO NEWSPAPERS

REPRESENTED THE BATTLE WITH GENERIC SCENES OF SOLDIERS FIGHTING IN THE

WOODS. (NPS COLLECTION)

|

At that moment the first salvo of Union shells shrieked over the belt

of trees and landed on Foster's farm. The Indians had never experienced

artillery fire before and were terrified by the explosions that seemed

to come out of nowhere. They fled from the field and played only a

marginal role in the remainder of the battle. The barrage scattered many

of the other Confederates as well and convinced McCulloch that he could

not push on to Elkhorn Tavern and leave such a substantial enemy force

in his rear. He made the critical decision to halt his eastward movement

toward Telegraph Road and deploy his entire division to the south

against Osterhaus. Tired and distracted by the chaotic state of affairs

on Foster's farm, McCulloch failed to inform Van Dorn of his decision,

which meant that the reunion of the two wings of the Army of the West at

Elkhorn Tavern would be delayed for several hours at least. The fight at

Leetown—the western half of the two-part battle of Pea

Ridge—was unfolding.

|

|