|

In the deepening twilight Van Dorn emerged from Cross Timber Hollow

onto the high ground around Elkhorn Tavern. At last he was atop Pea

Ridge. A few hundred yards south of the tavern he reached the junction

of Telegraph and Ford Roads. The perplexed Confederate commander

searched to the west but there was no sign of McCulloch's division. Van

Dorn finally had learned of McCulloch's death (which had occurred four

hours earlier), but he still was unaware of the dimensions of the

disaster that had befallen the Texan's powerful division. With only half

of the Army of the West on hand for the climactic moment of the battle,

Van Dorn nonetheless decided to make a final effort to sweep away the

stubborn Yankees still clinging to Telegraph Road and win the day. There

was no time for the Confederates to reconnoiter or maneuver. Van Dorn

ordered an immediate frontal assault against Carr's compact blue line,

dimly visible across Ruddick's field.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

BOTH ARMIES DEPLOY FOR A SHOWDOWN FIGHT ALONG TELEGRAPH ROAD, NIGHT, MARCH 7, 1862

During the night of March 7-8, both commanders concentrated their

forces on Telegraph Road. Curtis abandoned the Little Sugar Creek

fortifications and sent every available man to bolster Carr. Van Dorn

moved part of McCulloch's division around Big Mountain to join Price,

but part of the division wandered away to the west. Also far to the west

at Camp Stephens was the Confederate ammunition train, which had somehow

become separated from the army.

|

Unseen by the Confederates in the gloom, Curtis and Asboth arrived at

this critical juncture leading hundreds of fresh troops and additional

guns from Little Sugar Creek to bolster Carr's weary, rattled men.

Shortly afterward the final Confederate attack began. About 3,000

Missourians from both Confederate and State Guard units surged across

the fields on either side of Telegraph Road directly toward the Union

line. Crouched behind a fence, Vinson Holman of the 9th Iowa heard

"their cheers and yells rising above the roar of artillery." But not for

long. Blasts of canister from Union guns lined up wheel to wheel plowed

dreadful lanes through the ranks of the oncoming Rebels. Despite the

mounting slaughter, a few hundred Missourians pressed on. "By this time

it was almost dark," remembered Asa Payne, "and we got so near the

battery that the fire from the guns would pass in jetting streams

through our lines." When the Missourians finally staggered to a halt

only fifty yards from Carr's position, the Union infantry rose up and

fired.

|

COLONEL ELKANAH GREER, 9TH TEXAS CAVALRY (HAROLD B. SIMPSON CONFEDERATE

RESEARCH CENTER, HILL COLLEGE)

|

The ghastly affair was over in less than fifteen minutes. Shaken

survivors of the doomed assault streamed back to the woods around

Elkhorn Tavern while the Federals cheered and jeered in triumph.

|

The ghastly affair was over in less than fifteen minutes. Shaken

survivors of the doomed assault streamed back to the woods around

Elkhorn Tavern while the Federals cheered and jeered in triumph. The

valiant but costly attack in Ruddick's field late on March 7 was the

high-water mark of the Confederate war effort west of the Mississippi

River and the final instance in which Van Dorn held the initiative at

Pea Ridge. Henceforth, Curtis would control the course of the

battle.

During the afternoon Curtis gradually came to the realization that he

had underestimated Van Dorn's audacity: all evidence indicated that the

entire Confederate army had gotten around his right flank and was in his

rear. This meant that the Army of the Southwest was facing the wrong

way. If he was to avoid disaster he had to turn the army around as

quickly as possible. And so, while fighting raged at Leetown and Elkhorn

Tavern, the Union army commenced a 180-degree change of front from south

to north. Curtis and his staff gradually shifted combat units northward

from the Little Sugar Creek fortifications to Pea Ridge. At the same

time, and on the same handful of narrow roads and lanes, they hurried

the army's ponderous supply trains southward out of harm's way. The

successful change of front in the midst of a battle was a complicated

undertaking unparalleled in the Civil War.

During the night of March 7, Curtis again demonstrated his mastery of

staff work by consolidating the dispersed Army of the Southwest into a

compact mass. He abandoned the Little Sugar Creek position entirely and

moved all of his scattered forces, including the victorious troops at

Leetown, to reinforce Carr's battered division straddling Telegraph

Road. He also saw to it that food, water, and ammunition were

distributed. There was a good deal of stumbling around in the dark, and

one column of troops (led, naturally, by Sigel) took a wrong turn and

was lost for several hours, but by dawn on March 8 the Union army was

reunited and ready for a second day of battle./P>

Van Dorn attempted to do much the same with the Army of the West, but

he was less successful. From his headquarters in the yard of Elkhorn

Tavern, he ordered Greer to gather up the fragments of McCulloch's

division and hurry to Elkhorn Tavern. As described earlier, Greer

dutifully led his skeletal command on an all-night march around Big

Mountain on Bentonville Detour and Telegraph Road. The troops and horses

arrived near dawn in such pitiful condition as to be almost useless. The

Confederates around the tavern were without food except for what was

found in Federal haversacks and sutlers' wagons. They also were without

adequate ammunition, for in the confusion of the march on Bentonville

Detour the previous night, the ammunition train had been left a dozen

miles distant at Camp Stephens in Little Sugar Creek valley. No one at

Confederate headquarters knew where the ammunition train was, and no one

thought to organize a search until the next morning. Van Dorn's failure

to organize and oversee a proper staff before launching the campaign now

began to take its toll.

Dawn broke on March 8 and Curtis waited to see if Van Dorn would

continue to press his attack. When nothing happened, Curtis concluded

that the Confederates had shot their bolt and that he now held the

initiative. He intended to attack and drive the enemy away from his line

of communications, but unlike the previous day, when hasty improvisation

was required, he proceeded in a methodical manner. Curtis formed the

entire Army of the Southwest into a long line of battle straddling

Telegraph Road.

|

THE CONFEDERATE POSITION ON THE MORNING OF THE SECOND DAY, WITH GOOD'S

TEXAS BATTERY IN THE FOREGROUND. UNION ARTILLERY, DIRECTED BY SIGEL,

OCCURRED THE HIGH, OPEN GROUND IN THE DISTANCE AND UNLEASHED A

DEVASTATING BOMBARDMENT. THE VIEW TO THE WEST FROM TELEGRAPH ROAD. (NPS

PHOTO BY BOB NORRIS)

|

Around eight o'clock all was in readiness. Curtis now did a peculiar

thing. He turned to Sigel, an officer he had come to distrust, and

directed him to take charge of the artillery massed in the rolling

fields west of Telegraph Road and prepare the way for a general assault.

Annoyed by Sigel's botched withdrawal from Bentonville on March 6,

Curtis had kept the German general sidelined at Little Sugar Creek

during most of the first day of battle. What caused Curtis to change his

mind and give Sigel a critical assignment on the second day is unknown,

but it turned out to be an inspired decision.

Pea Ridge may have been the only time in the Civil War that Sigel was

in his element. The former artillerist moved from battery to battery,

often dismounting to sight a gun personally, "encouraging the men and

giving his directions as cooly as if on parade." Sigel coordinated the

fire from six artillery batteries in a modern fashion by concentrating

on a single target until it was neutralized, then shifting to a second

target, and so on.

As Confederate counterbattery fire slackened and finally ceased under

the crushing hail of iron, Sigel advanced the guns and infantry west of

Telegraph Road until the opposing lines were only a few hundred yards

apart. By midmorning the Union army was in a curved or angled formation

over a mile in length; the left flank rested on Ford Road near the foot

of Big Mountain, the right flank extended east of Telegraph Road.

The thunderous cannonade of March 8 at Pea Ridge lasted two hours. It

was the longest and most intense field artillery bombardment of the

Civil War up to that time. Union gunners fired over 3,600 rounds—a

rate of over thirty shots per minute, or more than one shot every two

seconds. Add to this the explosions of the shells and the Confederate

response, and it is no wonder that the tremendous noise could be heard

over fifty miles away in Fayetteville and Springfield. Captain Henry

Cummings of the 4th Iowa was at a loss for words and simply told his

wife: "It was the grandest thing I ever saw or thought of."

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE CONFEDERATE ARMY RETREATS IN THE FACE OF A POWERFUL

UNION ASSAULT, MORNING, MARCH 8, 1862

On March 8 Curtis opened a two-hour bombardment that wreaked havoc on

the tightly packed Confederate forces around Elkhorn Tavern. The

bombardment was followed by a massive infantry assault that drove the

Rebels off the field. Van Dorn, Price, and most of the Army of the West

retreated east on Huntsville Road, but Pike and the artillery fled north

into Cross Timber Hollow.

|

The devastation wrought on the Confederates was terrible. Outgunned

and low on ammunition, Van Dorn's artillery was wrecked or driven from

the field. "Such a cyclone of falling timber and bursting shells I don't

suppose was ever equaled during our great war," recalled a Missouri

gunner. Reflecting on the "perfect storm" of shot and shell that deluged

his Texas battery, Captain John J. Good considered it a "perfect miracle

that any of us ever came out." Halfway through the cannonade the

Confederate guns fell silent.

|

CAPTAIN JOHN GOOD'S TEXAS BATTERY IN ACTION, A WATER COLOR BY ANDREW

JACKSON HOUSTON, SON OF GENERAL SAM HOUSTON, PAINTED ABOUT 1885. (THE

HAROLD B. SIMPSON CONFEDERATE RESEARCH CENTER, HILL COLLEGE)

|

Confederate infantrymen positioned in the woods on either side of

Telegraph Road were not the primary targets of Sigel's methodical

bombardment, but they fared poorly nonetheless. Soldiers crouched

helplessly behind trees or hugged the ground to avoid the hail of Union

projectiles that overshot the Rebel guns. Shrapnel, splinters, branches,

and even entire trees crashed down on the men. Most unfortunate of all

were the soldiers huddled for protection amid the imposing sandstone

pillars on the eastern end of Big Mountain. Solid shot smashed into the

sandstone and sent fragments flying in all directions with murderous

effect. The Confederate line slowly but steadily disintegrated as dazed

or terrified soldiers drifted back to the relative safety of Cross

Timber Hollow. The sustained cannonade at Pea Ridge was one of the rare

instances during the Civil War in which a preparatory artillery barrage

effectively softened up an enemy position and paved the way for an

infantry assault.

|

PRICE (WITH HIS ARM IN A SLING) ORDERS HIS MEN TO LEAVE THE FIELD.

(BL)

|

A member of Curtis's staff observed that during the cannonade the

Union commander behaved "about as calmly and with as much composure as

if overseeing a farm." Around ten o'clock Curtis said to Sigel: "General,

I think the infantry might advance now." As Sigel passed orders down the

chain of command, the guns fell silent and nearly 10,000 Union soldiers

dressed ranks. The morning of March 8 at Pea Ridge was one of the rare

occasions in the Civil War when an entire army—infantry, artillery,

and cavalry—was visible in line of battle from flank to flank.

George Gordon of the 18th Indiana spoke for many Union soldiers when he

described the imposing martial array as "the grandest sight that I had

ever beheld." No record survives of what the Confederates thought.

|

PEA RIDGE NATIONAL MILITARY PARK

In 1887, a quarter-century after the guns fell silent at Pea Ridge,

Confederate veterans met to dedicate a stark shaft of marble near

Elkhorn Tavern. Two years later a joint reunion of Union and Confederate

veterans dedicated a second simple monument to a "united soldiery."

Unlike so many other Civil War battlefields awash in postwar monuments

and statuary of every size and style imaginable, Pea Ridge boasts only

these two weathered obelisks set in the rocky ground alongside Telegraph

Road.

As the years rolled by, the trickle of returning veterans slowed and

then ceased altogether, but interest in commemorating the battle and

preserving the battlefield continued. Attempts to establish a national

park began in 1914 and continued through the next two decades. All

failed because the federal government deemed battlefields west of the

Mississippi River to be of only minor importance. In the 1950s Civil War

centennial fever swept the nation and Governor Orval Faubus, a native of

near by Huntsville, led a movement to save Pea Ridge. At his urging, the

state of Arkansas purchased the entire battlefield in 1957 and presented

it to the federal government in 1960. Instrumental in laying out the

park boundary was National Park Service regional historian Edwin C.

Bearss, then stationed at Vicksburg. While the park was under

development, a Benton County organization called the Pea Ridge Memorial

Association placed historic markers at Cross Hollows, Camp Stephens, and

other key sites associated with the campaign.

Following three years of planning and construction, Pea Ridge

National Military Park was dedicated on May 31, 1963. Within the

4,210-acre park is all of the ground where significant action took place

and much of the ground where troops deployed and maneuvered. A detached

section includes the only surviving portion of the Little Sugar Creek

fortifications. An ongoing campaign of planting and clearing vegetation

is gradually restoring the battlefield to its wartime appearance. The

result is one of the few completely intact Civil War battlefields in the

nation.

|

THE 1887 CONFEDERATE MONUMENT, FOREGROUND, AND THE 1889 MONUMENT. THE

TWO STARK SHAFTS WERE PRODUCED BY LOCAL ARTISANS AND REFLECT THE

STRENGTH AND SIMPLICITY OF OZARK PIONEER CULTURE. (NPS PHOTO BY BOB

NORRIS)

|

|

As drums rolled and bugles rang, the curving blue line swept across

the fields atop Pea Ridge, converging on Elkhorn Tavern from the west

and south. "That beautiful charge I shall never forget," wrote Captain

Eugene B. Payne of the 37th Illinois. "With banners streaming, with

drums beating, and our long line of blue coats advancing upon the double

quick, with their deadly bayonets gleaming in the sunlight, and every

man and officer yelling at the top of his lungs. The rebel yell was

nowhere in comparison."

Another Union soldier, Samuel P. Herrington of the 8th Indiana,

provided his impressions of the charge in what may be the nearest thing

we will ever have to a "live" report of a Civil War battle. "Forward

quick time guide right," Herrington frantically scribbled in his pocket

diary. "Halt make ready take aim fire. After first shot load at will.

Our guns a booming. The battery howling. Wounded groaning. Some excited,

I might say all. But we was going forward."

With thousands of wildly cheering and apparently unstoppable Yankees

closing in from the west and south, Van Dorn realized that his position

was hopeless and ordered an immediate withdrawal. The retreat rapidly

degenerated into a rout after Van Dorn and Price rode away to the east

on Huntsville Road, leaving thousands of their soldiers still engaged. A

few fought to the very end, including Colonel Benjamin Rives of the 3rd

Missouri, who was killed while his regiment covered the withdrawal of

other Confederate units. But many Rebels concluded, with good reason,

that they had been abandoned by their leaders and fled in all

directions.

While the Confederates tried to get away, the soldiers of the Army of

the Southwest rapidly recovered all the ground lost by Carr's division

the previous day. Curtis rode up Telegraph Road behind his advancing

line, enthralled by the fierce grandeur of battle. "A charge of infantry

like that last closing scene has never been made on this continent," he

told his brother. "It was the most terribly magnificent sight that can

possibly be imagined." At Elkhorn Tavern Curtis shook hands with Sigel,

then rode among his wildly yelling men, waving his hat and shouting

"Victory! Victory!"

The soldiers of the Army of the Southwest were dazed by the speed and

completeness of their triumph. "It was sometime before I could convince

myself that we had indeed won, so hard had been the fighting, so

hopeless the issue for two days," wrote an officer in the 59th Illinois.

But victory it was, and everyone from generals to privates took a few

minutes to congratulate themselves and each other on their good

fortune.

|

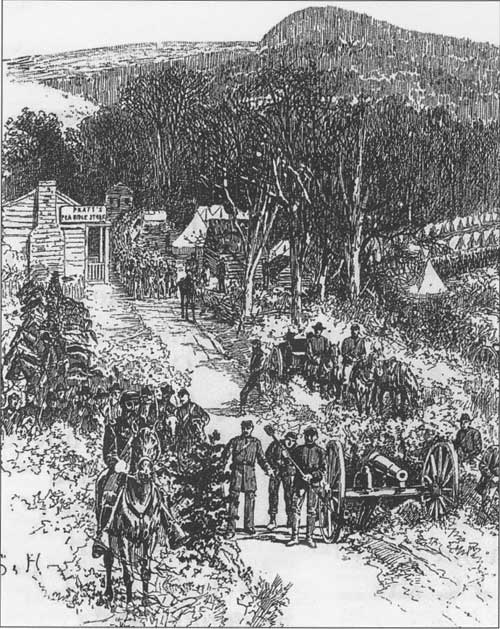

PRATT'S STORE ON TELEGRAPH ROAD WAS THE CENTER OF UNION ACTIVITY.

CURTIS'S HEADQUARTERS WAS IN ONE OF THE LARGE TENTS. (BL)

|

Because the dissolving Army of the West escaped on three different

roads leading north, east, and west, Curtis did not organize an

effective pursuit. Instead he scoured the countryside for Rebel

stragglers, collected wagonloads of discarded weapons and equipment, and

settled down to care for the wounded of both armies. The latter task was

particularly difficult because of the paucity of adequate medical

facilities, personnel, and supplies in a frontier region.

Not until the next day did Curtis learn that the bulk of the

Confederates were making their way back to the Boston Mountains on the

east side of White River. He sent a courier racing north to the

telegraph office in Springfield with a message for Halleck in St. Louis:

"Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Ohio, and Missouri very proudly share the

honor of victory which their gallant heroes won over the combined forces

of Van Dorn, Price, and McCulloch at Pea Ridge, in the Ozark Mountains

of Arkansas. Missouri was safe for the foreseeable future.

A conservative estimate is that the Confederates lost upwards of

2,000 of the 12,000 to 13,000 troops actually engaged in the battle, a

casualty rate of roughly 15 percent.

|

The Union triumph did not come cheap. Pea Ridge cost the Federals

1,384 casualties: 203 killed, 980 wounded, and 201 missing,

approximately 13 percent of the 10,250 troops engaged in the battle.

Confederate casualties are less certain because Van Dorn submitted

inconsistent (and implausible) reports of his losses. The Army of the

West consisted of over 16,000 men at the outset of the campaign but

suffered serious attrition en route to Pea Ridge. A conservative

estimate is that the Confederates lost upward of 2,000 of the 12,000 to

13,000 troops actually engaged in the battle, a casualty rate of roughly

15 percent.

The Confederate retreat from Pea Ridge was even more disastrous than

the advance. Late on the evening of March 8 most of the Army of the West

reassembled at Van Winkle's Mill southeast of the battlefield. The

primary problem facing the Confederates was sustenance. The three-day

supply of rations issued in the Boston Mountains on March 3 had long

since been consumed. The famished men and animals devoured everything in

sight, but the rugged, sparsely populated Ozark countryside east of

White River provided only a fraction of the food and forage necessary to

feed such a hungry horde. "I never knew what it was to want for

something to eat until the last fifteen days," Tom Coleman of the 11th

Texas Cavalry confided to his parents. Samuel B. Barron of the 3rd Texas

Cavalry believed he was "in much greater danger of dying from starvation

in the mountains of northern Arkansas than by the enemy's bullets."

Hundreds of Rebels wandered away in search of food and never returned to

the ranks. The trail of the defeated army was littered with discarded

clothing, weapons, and even flags.

For the next week the pathetic column trudged up the narrowing valley

of the West Fork of White River and over the crest of the Boston

Mountains. The Confederates did not return to their original camps on

Telegraph and Cove Creek Roads, which lay a dozen impassable miles to

the west, but continued south down Frog Bayou to the Arkansas River. By

the time they finally reached the vicinity of Van Buren, they were a

pitiful remnant of the army that had opened the campaign two weeks

earlier.

|

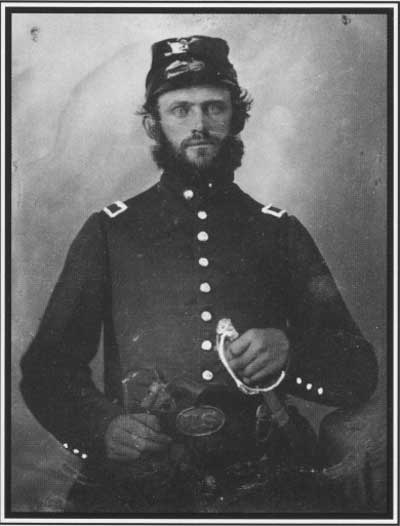

LIEUTENANT JESSE C. BLISS, 44TH ILLINOIS (UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS,

FAYETTEVILLE, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

|

While his troops recuperated, Van Dorn received a telegram from

General P. G. T. Beauregard. He encouraged Van Dorn move his command to

Corinth, Mississippi, as part of a concentration of all Confederate

armies west of the Appalachian Mountains. The purpose of this grand

design was to defeat Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Union army camped

at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. Van Dorn agreed and began

shifting his force eastward from Van Buren. Heavy spring rains slowed

the march, and the troops did not begin boarding steamboats until April

6. By then it was too late. The battle of Pittsburg Landing or Shiloh

was under way, a battle the Confederacy might have won had Van Dorn's

thousands of soldiers and dozens of cannons been present.

Van Dorn did more than merely transfer his army from one side of the

Mississippi River. He all but abandoned Arkansas and Missouri to the

enemy. Acting on his own authority, Van Dorn carried away nearly all

troops, weapons, ammunition, equipment, stores, machinery, and animals

in the vast area under his command. The former Federal posts at Little

Rock and Fort Smith, the objects of so much contention during the heady

days of secession, were stripped of everything of military value. One

can only wonder whether Van Dorn really understood the political and

military ramifications of his actions.

With the now-misnamed Army of the West in Mississippi, and with

outraged Arkansas and Missouri political leaders appealing for help,

Beauregard assigned command of the denuded District of the

Trans-Mississippi to Major General Thomas C. Hindman, a fiery Arkansas

politician. Apparently Beauregard considered Hindman to be a one-man

army for he neglected to provide him with any troops. When the new

commander arrived in Little Rock at the end of May he was shocked. "I

found here almost nothing," Hindman complained. "Nearly everything of

value was taken away by General Van Dorn." Hindman slowly rebuilt

Confederate military strength west of the Great River, but his premature

attempt to regain northwest Arkansas in December 1862 came to grief at

Prairie Grove, about forty miles southwest of Pea Ridge.

When Curtis learned that Van Dorn was moving down the Arkansas River,

he also shifted eastward in order to protect Missouri's vulnerable

southern flank. For several weeks the Union army struggled across the

central portion of the Ozark Plateau, a scenic but exceedingly rugged

and desolate region. By the end of April Curtis knew that Van Dorn had

crossed into Mississippi, so he again turned south and drove into

north-central Arkansas.

|

GOOD'S AND WADE'S GUNS FROM THE UNION PERSPECTIVE. (NPS PHOTO BY BOB

NORRIS)

|

No longer required to shield Missouri, Curtis now invaded Arkansas in

earnest. The Army of the Southwest reached Batesville on May 2 and

Searcy on May 11. Curtis was hampered by enormous logistical

difficulties, but he came within fifty miles of Little Rock before the

overland supply route from Missouri reached the breaking point. (Fifty

miles was too close for Governor Rector. Instead of attempting to defend

the city where he had done so much to encourage secession, he packed up

the state archives and fled to Hot Springs. He was much ridiculed and

failed to win reelection.) By this time both Halleck and Sheridan had

joined Grant's army in Tennessee, and their absence was felt in Missouri

and Arkansas. When efforts to create an alternate supply route via the

Mississippi and White Rivers failed, Curtis veered away from Little Rock

and turned east toward the Mississippi River, where his little army

could rest and refit.

Curtis brushed aside several feeble Confederate attempts to halt his

progress across the vast alluvial plain of eastern Arkansas. The largest

such engagement occurred on July 6 at Cache River, near Cotton Plant. It

was a one-sided affair that resulted in the death of 6 Union soldiers

and up to 136 Confederate soldiers.

On July 12 the Army of the Southwest marched into Helena on the

Mississippi River, finally bringing the long campaign to a close. For

the rest of 1862, until Grant began operations against Vicksburg, Curtis

could boast that his command in Helena was "farthest south." The town

remained in Union hands for the duration of the war. It was a major

staging area during the Vicksburg campaign and a primary recruiting

center for black troops. On July 4, 1863, a Confederate army attempted

to recapture Helena but was repulsed with terrible losses. Helena was

the jumping-off point for the campaign that resulted in the capture of

Little Rock and Fort Smith in September 1863 and the liberation of the

two Federal installations that had been the focal point of the secession

crisis two years earlier.

The Pea Ridge campaign was one of the most remarkable operations of

the Civil War. During the first six months of 1862, the Army of the

Southwest marched over seven hundred miles from Rolla to Helena, crossed

some of the most difficult terrain in the country, and fought and won a

major battle against imposing odds. Halleck and Curtis achieved their

primary strategic objectives of securing Missouri and freeing Union

resources for use elsewhere. In addition, they dealt Arkansas a heavy

blow. From the Union perspective, the campaign was a tremendous

success.

Exactly the opposite was true from the Confederate perspective. Van

Dorn, McCulloch, and Price lost Missouri and failed to defend Arkansas

effectively. It is no exaggeration to say that the Pea Ridge campaign

permanently altered the balance of power in the Trans-Mississippi. Few

Civil War operations had such an impact on the course of events.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

Pea Ridge

|

|

Back cover: Elkhorn Tavern photograph from the Pea Ridge NMP

collection.

|

|

|