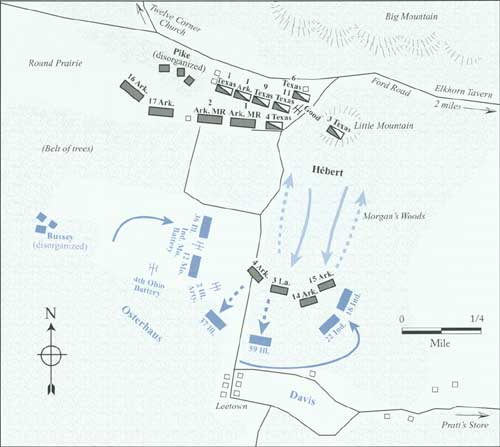

Despite the temporary disarray in his ranks, McCulloch was confident

of success as he prepared for a general assault against Osterhaus's

short blue line on the south side of Oberson's field. "In one hour they

will be ours," he remarked to an aide. Hébert's infantry formed a

line of battle straddling Leetown Road. Because the formation was too

long and unwieldy for Hébert to oversee by himself, McCulloch

divided the infantry into two wings. Hebért personally directed the four

regiments in the thick woods on the east side of the road, while

McCulloch assumed temporary command of the five regiments in the

well-trampled fields west of the road. McIntosh's cavalry regiments, now

largely restored to order, took their places behind the infantry, while

Pike struggled without much immediate success to reform the demoralized

Cherokees in the woods to the northwest.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE FEDERALS SMASH MCCULLOCH, AFTERNOON, MARCH 7, 1862

Late in the afternoon, Hébert led four regiments against

Davis's division. After some initial gains, the attack faltered when

Union forces struck both flanks. Hébert was captured and the

Confederates withdrew in disorder. While this was taking place in

Morgan's Woods, the bulk of McCulloch's division remained inert on

Foster's Farm.

|

After talking things over with Hebért near Leetown Road, McCulloch

rode westward along the Confederate line, conferring with subordinates

and encouraging the weary soldiers. The infantry formation west of

Leetown Road consisted of the 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion (dismounted),

1st and 2nd Arkansas Mounted Rifles (dismounted), and 17th and 16th

Arkansas. When he reached the western end of the line McCulloch noticed

a brushy gap in the belt of trees and decided to observe the Yankees in

Oberson's field for himself. "I will ride forward a little and

reconnoiter the enemy's position. You boys remain here," he told his

staff, "your gray horses will attract the fire of the

sharpshooters."

McCulloch had developed the habit of personal reconnaissance during

his years with the Texas Rangers. The technique had served him well in

Mexico and on the Great Plains, but at Pea Ridge it proved fatal.

Osterhaus had no sharpshooters in his command, but Greusel had sent two

companies of the 36th Illinois across Oberson's field to form an

advanced skirmish line. The Illinois soldiers spread out behind a rail

fence that ran along the north side of the field and marked the southern

edge of the belt of trees. Nervous about being so far out in front of

the main Union line, the infantrymen peered into the woods, alert for

any sign of enemy activity.

|

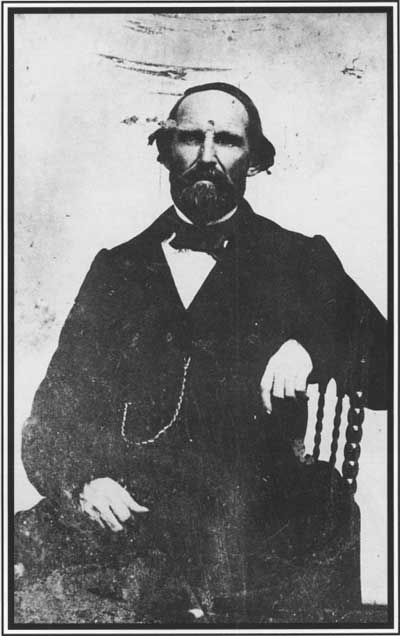

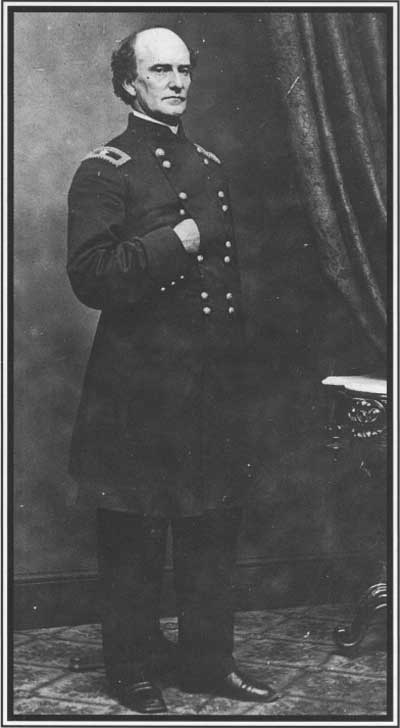

BRIGADIER GENERAL BEN MCCULLOCH (UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS AT LITTLE ROCK

ARCHIVES)

|

After a few minutes the Union soldiers on the west end of the

skirmish line saw a horseman riding in their direction through a brushy

gap in the trees. Clad in a black suit and mounted on a tall horse,

McCulloch was sharply outlined against a wintry blue sky. Dozens of

Union soldiers steadied their rifles on the fence and fired a ragged

volley. McCulloch tumbled from the saddle, killed by a bullet through

the heart. Because of the brown foliage that clung to the trees even at

the end of winter, no one in the Rebel ranks saw him fall.

For nearly an hour the entire Confederate force at Leetown remained

immobile, awaiting orders to advance, but no orders ever came. McCulloch

seemed to have vanished into thin air. His fate remained unknown until

midafternoon when the soldiers of the 16th Arkansas advanced through the

belt of trees to drive off the Union skirmishers and stumbled across his

body. Command of the division belatedly passed to McIntosh, who ordered

the general assault to begin. Instead of remaining in the rear as

befitted a division commander, McIntosh impulsively decided to go into

the fight with his old regiment, the 2nd Arkansas Mounted Rifles. But

the Arkansans were dismounted and serving as infantry now, and as they

slowly picked their way through the belt of trees, McIntosh grew

impatient and rode forward alone.

|

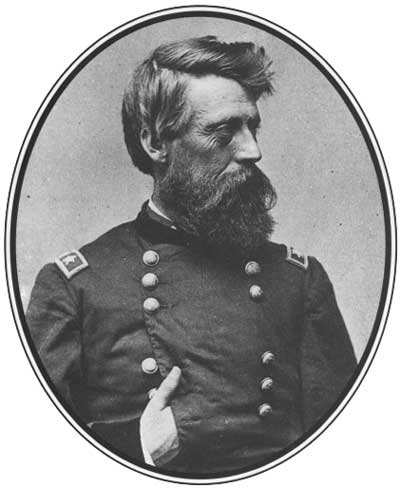

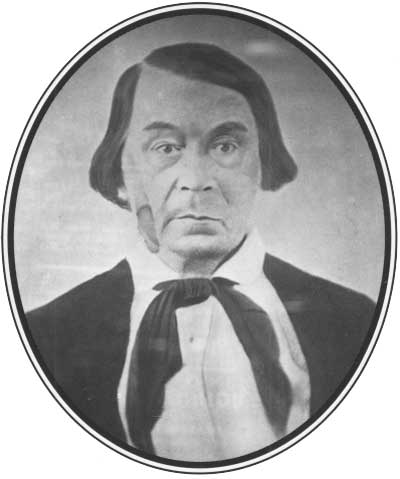

COLONEL JEFFERSON C. DAVIS (USAMHI)

|

A short time earlier, Greusel had led the main body of the 36th

Illinois halfway across Oberson's field to recover the two companies of

skirmishers, who were engaged in a firefight with the 16th Arkansas.

When Greusel saw the 2nd Arkansas Mounted Rifles—with McIntosh out

in front—emerge from the belt of trees just to the east of the 16th

Arkansas, he directed the 36th Illinois to shift to this new target.

Seven hundred Union muskets roared and McIntosh toppled over, struck by

a bullet through the heart. He fell about two hundred yards east of the

spot where McCulloch had died in an almost identical fashion.

The loss of McCulloch and McIntosh caused the abortive Confederate

infantry assault west of Leetown Road to sputter out. Most regiments had

not moved an inch, and the few that had started forward through the belt

of trees, such as the 16th Arkansas and 2nd Arkansas Mounted Rifles,

wavered and then fell back to their starting point on Foster's farm.

After the Rebels faded back into the belt of trees and disappeared, the

36th Illinois waited uncertainly in Oberson's field, well out in front

of the other Union regiments. When nothing happened, a mystified Greusel

led the Illinoisans back to their original position on the south side of

Oberson's field to await developments.

Meanwhile, Hebért's wing of the Confederate infantry line of battle,

consisting of the 4th, 14th, and 15th Arkansas and 3rd Louisiana, was

deployed east of Leetown Road in a forested area known as Morgan's

Woods.

Hébert never learned that McCulloch and McIntosh were dead and

that he was the ranking officer in the division. When he heard the

sporadic firing to the west that felled his superiors, he assumed it

marked the beginning of the general assault that he and McCulloch had

discussed. Hebért waited in vain for the order to advance. Determined to

strike a blow, he finally decided to go forward on his own and led his

four regiments south through the woods. An Arkansas soldier proudly

remembered that despite being tired, hungry, and footsore, he and his

comrades "went in with all the vim and courage that regulars could have

displayed." Unable to see any distance ahead, the Confederates

unknowingly marched directly toward the exposed right flank of

Osterhaus's short line, which did not extend east of Leetown Road.

The confusion and delay occasioned by the deaths of McCulloch and

McIntosh allowed the Union defenders just enough time to blunt Hebért's

attack. When Curtis received Osterhaus's message begging for support, he

dispatched Colonel Jefferson C. Davis's division to the scene. Davis,

33, was a capable West Pointer who, somewhat unfairly, is best known

for his memorable name and for murdering another Union general in a

personal dispute a few months after Pea Ridge.

Davis pulled his troops out of the Little Sugar Creek fortifications

and reached Osterhaus's position with three Illinois and Indiana

regiments—about 1,400 men—and the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery

Battery. As a Union band incongruously tootled "Dixie," the infantry

hurried into Morgan's Woods on the east side of Leetown Road. The new

regiments extended the Union line directly across Hébert's path.

Colonel Julius White's brigade composed of the 37th and 59th Illinois

was first into line, so Davis sent it forward to locate the enemy.

Neither Davis nor White realized that the two Illinois regiments were on

a collision course with Hebért's much larger force.

|

THE 37TH ILLINOIS BATTLING HÉBERT'S BRIGADE IN MORGAN'S WOODS.

(NPS COLLECTION)

|

Hébert's Rebels and White's Yankees plowed blindly into each

other in Morgan's Woods and opened fire at extremely close range.

"Suddenly something like a tremendous peal of thunder opened all along

our front," recalled William Watson of the 3rd Louisiana. Staggered by

the shock, both lines ground to a halt and an intense firefight erupted

in the tangled woods. An Illinois soldier recalled that the air around

him was "literally filled with leaden hail. Balls would whiz by our

ears, cut off bushes closely, and even cut our clothes."

Soldiers on both sides lay down to avoid the deadly fire. Captain

Henry Curtis, Jr., of the 37th Illinois told his mother that his men

"would have been utterly annihilated" had he not "fought them flat on

their bellies on the ground." Parade ground maneuvers and fancy tactics

counted for little in such a fight. As regimental formations broke down

on both sides, the struggle degenerated into firefights between

company-sized groups stumbling around in the smoky wilderness.

Hébert's men had the advantage in numbers and they gradually

pushed White's Illinoisans back. "At the flash of the enemy's guns,"

wrote Captain Jerome Gilmore of the 3rd Louisiana, "the men would rush

madly on them, routing them from behind logs, stumps and trees, shooting

them at almost every step." At one point in the contest a hundred or

more soldiers from the 3rd Louisiana and 4th Arkansas became separated

from their units and emerged from the western edge of Morgan's Woods.

Spying the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery Battery in the southeast corner

of Oberson's field only a hundred yards away, they surged across Leetown

Road toward the Union guns in a disorganized mass.

|

COLONEL JULIUS WHITE (USAMHI)

|

The Confederates were momentarily brought to a halt by a single man,

Captain William P. Black of the 37th Illinois, who stood in front of the

imperiled battery and blasted away with a Colt repeating rifle until

being wounded. Black's remarkable act earned him a Medal of Honor and

gave the artillerymen time to save four of their six guns. The

Confederates swarmed over the two remaining guns and, for a moment, it

seemed as if Hebért had achieved a breakthrough. But then Osterhaus's

regiments on the west side of the imperiled Union battery came to the

rescue. The 36th Illinois and 12th Missouri wheeled out into Oberson's

field and drove the Rebels away from the guns. Hebért's men sprinted

across Leetown Road under a hail of fire and plunged back into Morgan's

Woods.

Shortly before the Confederates made their sideways lunge into

Oberson's field, Davis sent Colonel Thomas Pattison's brigade,

consisting of the 18th and 22nd Indiana (which he had reclaimed from

Osterhaus), around the left flank of Hebért's formation. Pattison was

slow to get into position, and his counterattack was hampered by poor

visibility in the woods. Navigating by compass, the Hoosiers formed a

line of battle facing west and groped forward until they encountered the

Rebel flank. Surprised by the unexpected appearance of the Yankees, who

seemed to come out of nowhere, the soldiers of the 14th and 15th

Arkansas nevertheless managed to change front to their left. They put up

a stiff defense amid the tangle of trees and vines and fought the two

Indiana regiments to a standstill. Lieutenant Colonel John A. Hendricks

of the 22nd Indiana was killed in the encounter.

During the chaotic moments when the Confederates struggled to meet

Pattison's flank attack, Hebért and Colonel William C. Mitchell of the

14th Arkansas became disoriented in the smoky woods and drifted away

from their own men. About the same time Colonel William F. Tunnard of

the 3rd Louisiana collapsed from exhaustion. All three officers were

captured by the Yankees. Hebért's loss was a particularly telling blow,

for it effectively completed the decapitation of McCulloch's division

and left it leaderless and dysfunctional.

The combination of stiffening Union resistance in front and flank and

the loss of three key senior officers brought Hebért's bold attack to an

end. Exhausted, disorganized, and out of ammunition, the Arkansas and

Louisiana troops gave up the fight and streamed to the rear through the

darkening forest. Upon reaching Foster's farm, they were disgusted to

discover that over two-thirds of McCulloch's division had stood idle

during their desperate struggle in Morgan's Woods. Not a single

Confederate regimental commander west of Leetown Road had demonstrated

any initiative during the most critical phase of the battle.

|

THE LANE AT THE SOUTH END OF MORGAN'S WOODS. (NPS PHOTO BY BOB NORRIS)

|

The failure of Hebért's unsupported attack, and the capture of Hebért

himself, were the final blows to the ill-starred Confederate effort at

Leetown. By four o'clock the fighting had sputtered out except for

intermittent artillery fire. Leaderless and listless, the officers and

men of McCulloch's division milled around in the lengthening shadows and

waited for someone to tell them what to do. After some hesitation, Pike,

a nominal brigadier general as commander of the Cherokee regiments,

attempted to assume command, but many of McCulloch's officers refused to

recognize his authority. Pike eventually led a half dozen regiments and

battalions back to Twelve Corner Church. From there the column made its

way in the gathering darkness along Bentonville Detour and Telegraph

Road to the vicinity of Elkhorn Tavern. Upon reaching the rear of

Price's division a few hours before midnight, the exhausted, famished

soldiers collapsed in heaps.

Pike was right to attempt to concentrate the army, but his

intervention only made things worse. When he marched off in search of

Van Dorn and Price with about half of McCulloch's division, he left the

other half behind on Foster's farm. As darkness spread across Pea Ridge,

some regiments of McCulloch's division took themselves out of the fight

altogether and drifted westward toward Camp Stephens in Little Sugar

Creek valley. Colonel John Drew and the men of the 1st Cherokee Mounted

Rifles decided they had earned their pay and headed back toward the

Indian Territory. Finally, Colonel Elkanah Greer of the 3rd Texas

Cavalry took command of who was left and retired a short distance

northward to Twelve Corner Church.

Around midnight Greer received an order from Van Dorn to follow the

same route around Big Mountain that Pike had taken. By the time Greer's

woebegone troops rejoined their comrades near Elkhorn Tavern, it was

almost dawn on March 8. Having been without rest or food for two days

and nights, the men tumbled out of ranks and fell fast asleep on the

cold, rocky ground. McCulloch's division—or what was left of

it—would play only a minimal role in the second day's battle.

The four hours of confused, sporadic fighting in the fields and woods

around Leetown had significant consequences. Osterhaus suffered a sharp

tactical reverse at the outset of the battle, but he succeeded admirably

in achieving his primary objective of disrupting Confederate plans.

Davis arrived with reinforcements at exactly the right time and place to

blunt the only major Confederate thrust of the day. The Union force at

Leetown was outnumbered from start to finish, but it was blessed with

remarkable good fortune and able leadership at the division and brigade

levels. In only a few hours of sporadic fighting the hard-pressed

Yankees killed or captured five senior Confederate officers (while

losing only one senior officer of their own) and neutralized a powerful

Confederate force.

|

COLONEL JOHN DREW, 1ST CHEROKEE MOUNTED RIFLES (OKLAHOMA HISTORICAL

SOCIETY)

|

|

ANOTHER GENERIC AND WHOLLY IMAGINARY DEPICTION OF THE BATTLE. (FW)

|

McCulloch and his principal lieutenants initially responded well to

the unexpected encounter at Leetown, but everything seemed to go wrong

after that. Though McCulloch's division suffered relatively few

casualties, it was reduced to a disorganized, demoralized shambles and

effectively knocked out of the battle without ever really landing a

blow. The most important result of the fight at Leetown, however, was

that it kept the Army of the West divided and unable to make effective

use of its numerical superiority.