|

THE BATTLE OF STONES RIVER

General Braxton Bragg was a troubled man. In fewer than six months as

commander of the Army of the Mississippi, he had lost a major campaign

and earned the enmity of many of his principal lieutenants and troops.

As fall gave way to winter in 1862, a chill both real and psychological

settled over the Confederate heartland.

Bragg had taken command in June, when many believed the nadir of

Southern fortunes in the western theater already had been reached.

General Pierre G. T. Beauregard had abandoned Corinth, Mississippi, a

vital railroad junction town, and with it the northern portion of the

state. His withdrawal also opened the way to a Federal advance on

Chattanooga, gateway to the Deep South.

|

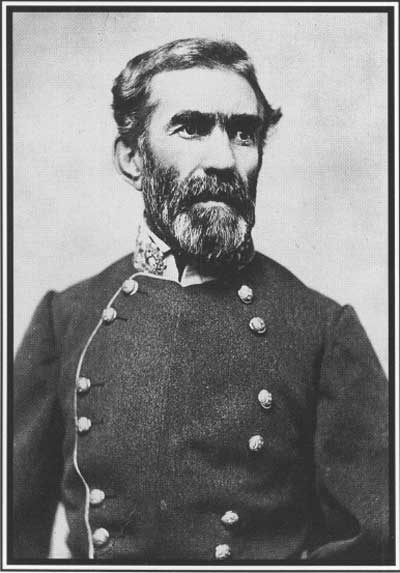

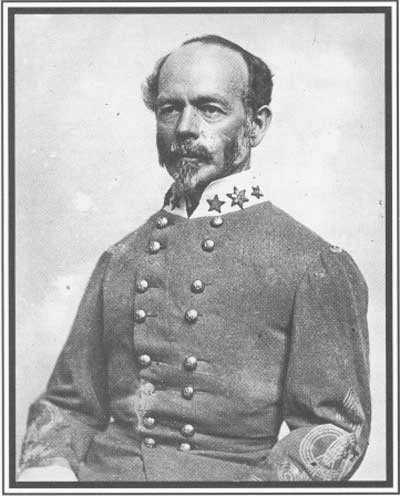

BRIGADIER GENERAL BRAXTON BRAGG (LC)

|

At that moment, Bragg stepped in to take charge of the army, lying

dormant at Tupelo. He faced three challenges: reopen the Memphis and

Charleston Railroad, which pumped supplies to the Atlantic seaboard;

protect Chattanooga; and recapture at least a portion of Tennessee. As

the defense of Chattanooga was most urgent, Bragg transferred his army

there, countering an advance against it by Major General Don Carlos

Buell's Federal Army of the Ohio. Having secured Chattanooga, Bragg, in

a rare state of exuberance, met with Major General Edmund Kirby Smith,

commander of the Department of East Tennessee, on July 31 to fashion a

plan to push northward into Kentucky. A successful thrust into that

state, Bragg believed, not only would relieve pressure on the Deep

South, but would return much of Tennessee to the Confederacy.

On August 14, Kirby Smith struck out for Lexington, Kentucky, which

he captured with ease, and, as agreed upon, remained there to await

Bragg's entry into the state. Bragg left Chattanooga two weeks later.

Like Kirby Smith, he initially outgeneraled his opposition. General

Buell, incorrectly supposing Bragg's objective to be Nashville, lost

valuable time trying to protect the Tennessee capital. Meanwhile, on

September 17, Bragg captured Munfordville, Kentucky, effectively

interposing his army between Buell and Louisville.

A spirit of elation infused the Army of the Mississippi: many

believed the campaign all but won. Munfordville lay astride Buell's

only practical route to Louisville and was easily defensible. Everyone

in Bragg's army expected a battle—and with it a decisive victory.

But for reasons that remain unclear, Bragg chose not to fight. He

ordered a withdrawal northeastward to Bardstown, opening the road to

Louisville. Buell was surprised, Kirby Smith "astonished and

disappointed," and Bragg's generals furious.

|

BATTLE OF MUNFORDVILLE AS SKETCHED BY HENRY LOVIE. (COURTESY OF MIRIAM

AND IRA D. WALLACH PRINT COLLECTION, NY PUBLIC LIBRARY)

|

|

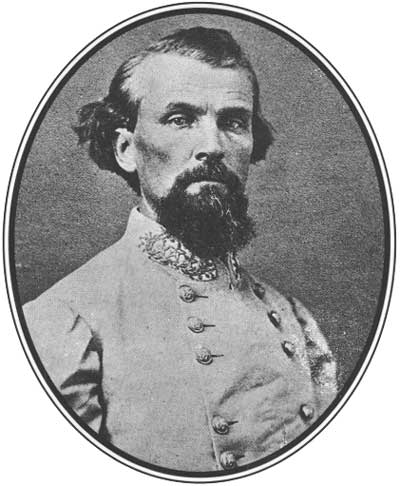

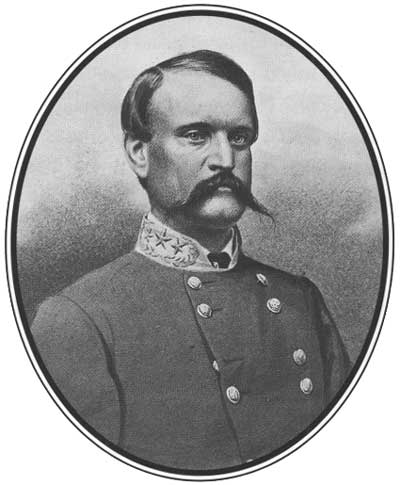

LIEUTENANT GENERAL NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST (LC)

|

While Federal prospects brightened, Bragg grew morose. As the Army of

the Mississippi fell back on Bardstown to await the inevitable Union

advance, the campaign lost its purpose and direction. While Buell

prepared to move on Bardstown, Bragg left his army to confer with Kirby

Smith at Lexington.

Buell struck while Bragg was away, coming up against portions of the

Rebel army at Perryville on October 7. Bragg returned in time to direct

the next day's fight, which ended with his army having driven the

Federals back more than a mile.

But Bragg had enough. A dyspeptic martinet plagued by numerous

ailments who could plan well but lacked both the confidence of his

subordinates and the energy needed for sustained efforts, he was

unwilling to sacrifice his army in what he believed was a bankrupt

campaign and so fell back to organize a retreat from Kentucky.

Bragg really had been looking over his shoulder for some time. In

late September he had sent Nathan Bedford Forrest to secure the Middle

Tennessee town of Murfreesboro and the surrounding country from the

depreciations of Union foragers. And on October 14, just two days after

choosing to abandon Kentucky, Bragg ordered Major General John C.

Breckinridge's division there as well.

With these dispositions, Bragg decided to occupy Middle Tennessee.

Although he never explained them, Bragg's reasons for choosing this

course of action are apparent. As the initial objective of the Kentucky

campaign was simply to restore to Confederate control a portion of

Tennessee, Bragg could argue that, by securing its central counties, his

campaign had succeeded. As to the choice of Murfreesboro in particular,

lying as it did astride the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, it was

the key to the rich Stones River Valley and, in Bragg's mind, to the

equally fertile Duck and Elk river valleys. Bragg's change of base was

facilitated by Buell's unwillingness to risk another battle. Content

simply to see Bragg go, he allowed his prey to descend the Cumberland

Gap into East Tennessee unmolested.

|

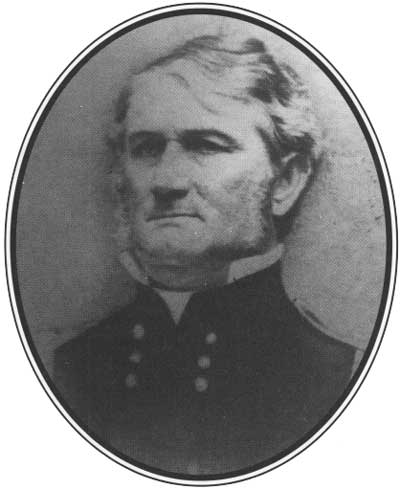

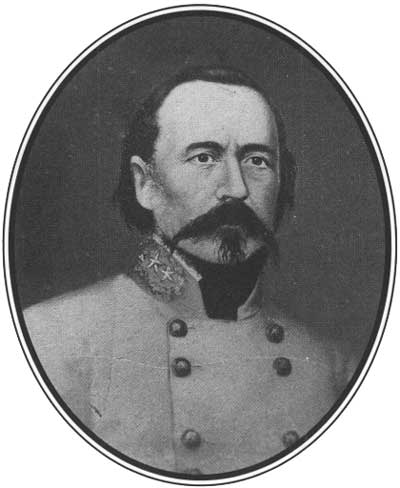

LEONIDAS POLK (USAMHI)

|

|

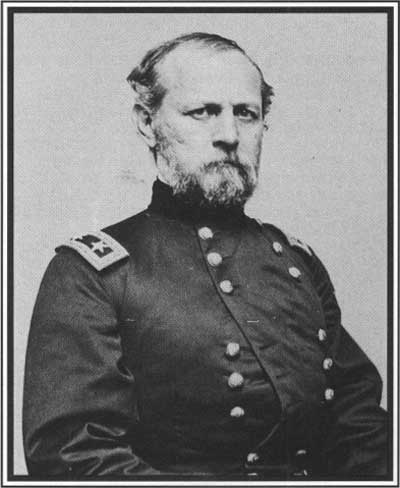

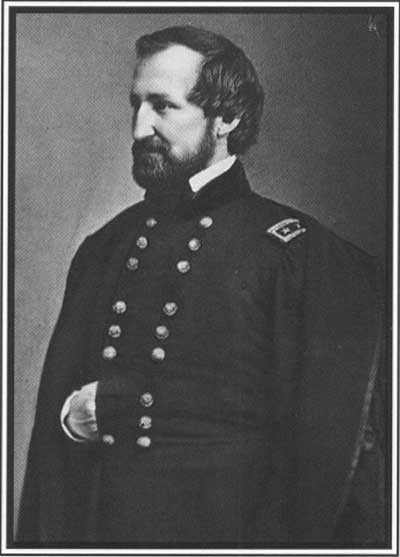

MAJOR GENERAL DON CARLOS BUELL (USAMHI)

|

But Bragg was hardly out of trouble. While the army recuperated at

Knoxville, he boarded a train for Richmond, Virginia, on October 31 to

win presidential approval for his planned move into Middle Tennessee

and to clear himself of blame for the Kentucky fiasco.

That he would succeed on the latter count was by no means certain.

His two principal subordinates, corps commanders William J. Hardee and

Leonidas Polk, were urging President Jefferson Davis to dismiss him:

only a change of commanders, they argued, could save the army and

salvage Confederate fortunes in the West. Kirby Smith added his voice to

the call for Bragg's removal, as did influential members of the

Confederate Congress and the always vitriolic Southern press.

But Davis chose both to sustain his old friend and to approve his

request to occupy Middle Tennessee. Polk and Kirby Smith both came to

Richmond after Bragg to press their demand, but Davis gently rebuffed

them. Davis neither replaced Bragg nor transferred Polk and Hardee,

leaving the army to enter Middle Tennessee with a high command torn by

dissension.

The Kentucky campaign elicited little enthusiasm in the North.

Although the state had been saved for the Union, many Northerners

considered the campaign a defeat, suggesting—with logic that would

have pleased Bragg—that the Confederacy, by regaining control of

Northern Alabama and Middle Tennessee, had ended with more than it had

begun. The press labeled Bragg's retreat from Kentucky an escape and

laid the blame on Buell.

|

MAJOR GENERAL WILLIAM STARKE ROSECRANS (LC)

|

He was an easy mark. Unpopular with his troops, Buell had also lost

the confidence of President Lincoln, who was angry that Bragg had been

allowed to withdraw. On October 24, he relieved Buell, naming in his

place Major General William Starke Rosecrans.

Rosecrans joined the army at Bowling Green on October 30. The same

general order that brought Rosecrans to the army also changed its name.

The Army of the Ohio was now the Fourteenth Army Corps, composed of a

left wing, right wing, and center. (On January 9—a week after

Stones River—the army was designated the Army of the Cumberland,

the name it would carry until the war's end.)

Although happy to be rid of Buell, the army was unsure what to make

of its eccentric new commander. A West Point graduate who had left the

service in 1853 to direct a Cincinnati coal company, Rosecrans brought

to the army many qualities of genius. He was erudite, animated, and

seemingly indefatigable. But he could also be indiscreet, intolerant,

and mercurial, with an impulsiveness that suggested instability under

pressure and a tendency to issue too many orders during combat.

Whatever his shortcomings, the army needed a commander with

Rosecrans's energy in the weeks following Perryville. The Kentucky

campaign had shattered morale, and Union communication and supply lines

were in a shambles. Marauding Rebel cavalry had ruined the railroad

between Louisville and Nashville, upon which the Federals depended both

for supplies from Louisville and communications with Nashville. More

threateningly, the presence of enemy troops on the outskirts of

Nashville gave rise to fears that the city itself might fall.

|

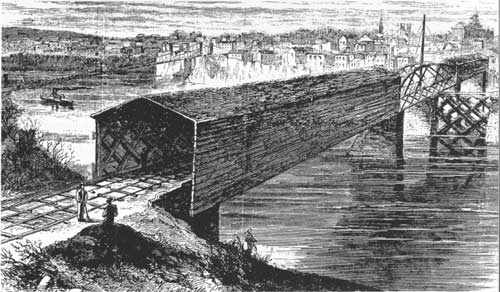

NASHVILLE LOOMS IN THE DISTANCE BEYOND THE CUMBERLAND RIVER.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

Rosecrans quickly met the perceived —though

illusory—danger, advancing the army to Nashville during the first

two weeks of November. Once settled into the Tennessee capital, he

turned his attention to the army's internal problems. He dismissed

incompetent officers by the score, looked to his soldiers' welfare, and

secured the appointment of the talented Brigadier General David Stanley

to command his inept and badly equipped cavalry. As morale improved,

Rosecrans concentrated on reorganizing the army. He structured its three

wings so as to approximate corps: The right and left wings each contained

three divisions of infantry and nine batteries of artillery; the center

contained five divisions and fourteen batteries. The right wing

mustered 15,832 present in early December, the left wing 14,308 and the

center 29,337.

That the center was the largest command in the army and that Major

General George Thomas led it was no accident. Perhaps the most able

defensive general the war produced, the native Virginian enjoyed the

affection of his men and the deep respect of Rosecrans, who leaned

heavily on him for advice.

Sadly, Rosecrans's remaining wing commanders left much to be desired.

Major General Alexander McCook, who led the right wing, already had

proven incompetent, although much had been expected of the arrogant

former West Point instructor. Fellow blowhard Major General Thomas

Crittenden, a Kentuckian with potent political connections but little

military sense, commanded the left wing. Having inherited the two,

Rosecrans was reluctant to relieve them.

|

ROSECRANS AND STAFF (USAMHI)

|

Lincoln appreciated Rosecrans's efforts in rejuvenating the Army of

the Cumberland but demanded more. As November drew to a close, the

administration began to pressure Rosecrans to advance before winter

forced an end to active campaigning. Their reasons were sound. The

fortunes of the Union, at least on the diplomatic front, were at their

nadir. Failure to conquer substantial amounts of Confederate territory,

or at least recapture lost ground, raised the specter of foreign

intervention on behalf of the South, particularly by Britain.

So now, in November, Washington prepared for a concerted drive by all

the major Union field armies. In Mississippi, Ulysses S. Grant made

ready an overland march against Jackson, supported by a demonstration

against Grenada by Major

General Samuel Curtis from eastern Arkansas. Grant hoped the capture

of Jackson would ensure the fall of Vicksburg. In Virginia, Major

General Ambrose Burnside moved the Army of the Potomac toward

Fredericksburg, placing General Robert E. Lee's communications with

Richmond in jeopardy. Lee hoped to receive reinforcements from the West.

They were not forthcoming, but the Lincoln administration recognized the

danger of a Southern interdepartmental troop transfer, although they

assumed Bragg would move into Mississippi against Grant, rather than

into western Virginia to relieve pressure on Lee. In any event, it

seemed imperative that Rosecrans keep him occupied.

|

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN C. BRECKENRIDGE (LC)

|

Unbeknownst to the authorities in Washington, Bragg had no objective

beyond the occupation of Middle Tennessee, which he completed on

November 26. Nor, as winter approached, was he concerned about a Federal

offensive. Instead, he turned his attention to reorganizing his depleted

forces. He consolidated the Army of the Mississippi and Kirby Smith's

Army of Kentucky into the Army of Tennessee, the name it was to carry

for the rest of the war. Three corps of infantry were created, led by

Polk, Hardee, and Kirby Smith.

Polk's corps contained three divisions. Major General Benjamin

Franklin Cheatham, a hard drinker and a hard fighter who was immensely

popular with his troops, most of whom were fellow Tennesseans, commanded

the first. Major General Jones Withers, a West Point graduate turned

lawyer, led the second. Major General John C. Breckinridge commanded the

third division. The most influential division commander in the army, the

Kentuckian had been vice-president in the ill-starred Buchanan

administration. He and Bragg bad fallen out over Bragg's unwarranted

conviction that Breckinridge was somehow responsible for the failure of

the Kentucky campaign, even though he had been on duty in Mississippi

with his division when it began and had tried to join Bragg's army in

time to take part in it.

|

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN P. MCCOWN (LC)

|

Lieutenant General William J. Hardee commanded Bragg's second corps.

An able lieutenant, Hardee was a professional soldier who had made a

name for himself before the war as author of the two-volume Rifle

and Light Infantry Tactics that came to be known simply as Hardee's

Tactics after being endorsed by the War Department.

Hardee profited from the services of two able division commanders.

Patrick Cleburne, an Irishman who had served in the British army before

immigrating to Arkansas, took command of the first in early December. A

born leader, he was held in high regard by both Hardee and Bragg.

Brigadier General Patton Anderson of Florida, one of Bragg's few allies

in the army, commanded the second division.

The remaining corps of the Army of Tennessee was composed of two

divisions that Kirby Smith had furnished Bragg led by Carter Stevenson

and John McCown, whom Bragg considered a misfit unworthy of command.

The cavalry also was reshuffled. Brigadier General Joseph Wheeler, a

twenty-five-year-old favorite of Bragg, was appointed chief of cavalry,

although there was little in his record to date, save loyalty to Bragg,

to merit such a promotion.

Bragg believed that the move into Middle Tennessee and reorganization

of the army was having a salutary effect. President Davis was

skeptical: too many reports of continued unrest within the officer corps

were reaching his office. Affairs outside of Tennessee disturbed him as

well. Cooperation in the West was at a minimum, coordinated action

nonexistent. While Bragg advanced into Middle Tennessee, Lieutenant

General John Pemberton was in peril of losing much of Mississippi,

including Vicksburg, to Grant's offensive. Pemberton turned to Bragg

(who as departmental commander was, on paper at least, his commander)

for reinforcements, but Bragg offered only words: he suggested that his

own move into Middle Tennessee might relieve pressure on Pemberton, to

the extent that it created a diversion in Grant's rear. Everyone

concerned but Bragg was upset. Bragg and Pemberton squabbled until November

24, when Davis intervened to unite the commands of Pemberton in

Mississippi and Bragg in Tennessee under General Joseph Johnston.

Johnston's responsibilities were as enormous as his resources were

limited. Davis expected him to coordinate the efforts of Bragg and

Pemberton so as to maintain control of the Mississippi River Valley. As

Tennessee was of secondary importance to Davis, he assumed that

Johnston would take from the Army of Tennessee such troops as might be

needed to save Vicksburg. But this Johnston declined to do, fearing that

Rosecrans would avail himself of the weakening of Bragg's army to march

unimpeded against Lee's flank in Virginia or to reinforce Grant; in

either case, he argued, Tennessee would be lost.

|

GENERAL JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON (LC)

|

Johnston's arguments convinced Davis only that it was time for a

presidential trip to the West. He arrived at Murfreesboro on December

12. Conversations with Bragg's lieutenants convinced him that

Rosecrans's intentions were purely defensive and that a winter campaign

was unlikely. With his doubts about the wisdom of a Mississippi

River—first strategy allayed, he ordered the reinforcement of

Pemberton with Carter Stevenson's seventy-five-hundred-man division and

a brigade from Henry Heth's division.

Stevenson's detachment prompted another reorganization of the army.

Kirby Smith's command, now reduced to McCown's division, was abolished.

McCown was attached to Hardee's corps, and Kirby Smith returned to East

Tennessee. As Breckinridge's division had been transferred to Hardee's

corps several days earlier, Anderson's division was disbanded and its

regiments divided between the two corps. But the detachment of Stevenson

did more than necessitate a reshuffling. It seriously weakened the army,

depriving it of one-sixth of its infantry—infantry that would be

sorely missed at Stones River.

In positioning his forces to cover the primary avenues leading to

Murfreesboro from Nashville, Bragg had scattered the Army of Tennessee

across a fifty-mile front, making rapid concentration problematical. But

this vulnerability did not trouble him or his generals, who with the

onset of winter became even more certain that Rosecrans would make camp

at Nashville until spring. Bragg was so sure of this that he sent Nathan

Bedford Forrest with two thousand cavalrymen into western Tennessee to

harass Grant and John Hunt Morgan with a similar force to strike deep

into Kentucky and wreck havoc on the Louisville and Nashville

Railroad.

|

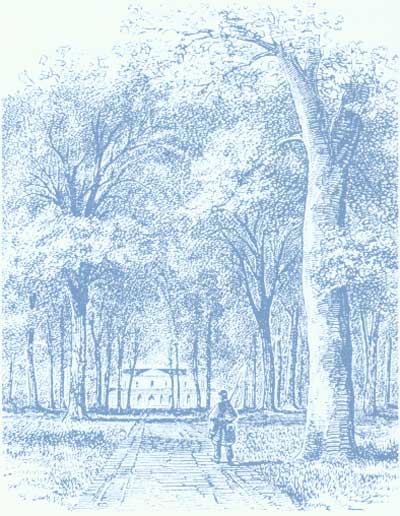

BRAGG'S MURFREESBORO HOME. (LOSSING'S CIVIL WAR IN AMERICA)

|

Sharing Bragg's conviction, his soldiers raised winter quarters

around Murfreesboro, the seat of Rutherford County. They found the town

a charming place in which to pass an idle winter. Thus far, it had

escaped the ravages of war. Murfreesboro's fine brick residences, clean

white fences, and oak- and elm-shaded streets were a pleasing contrast

to the destruction that already had visited many Southern towns. The

staunchly Confederate townspeople opened their homes to the troops, and

kitchen hearths turned out bread and cakes for the army.

As Christmas approached, Murfreesboro hosted a number of gatherings

that reinvigorated its languishing social life. Unusually clear skies

and mild temperatures helped to promote the festive spirit that pervaded

the normally strife-ridden Army of Tennessee. By Christmas eve the

skies had become overcast, but the temperature still hovered above

normal. That night, officers of the First and Second Louisiana

entertained the single women of Murfreesboro with a lavish ball at the

courthouse. "It was a magnificent affair," remembered a member of

Bragg's escort. Four large "Bs" of cedar and evergreen—signifying

Bragg, Beauregard, Buckner, and Breckinridge—adorned the walls.

While their officers danced and drank, the men in ranks passed the

holiday simply, but not necessarily more quietly. Gambling and cock

fights were common, and liquor flowed freely in the camps as well.

At Nashville, where the candles burned deep into the night at

departmental headquarters, the Yuletide bore a more somber aspect. After

weeks of threats from Washington, Rosecrans had agreed to move. He

correctly deduced that Bragg, not expecting an offensive before spring,

had gone into winter quarters around Murfreesboro after sending much of

his cavalry away. As Rosecrans later explained, "In the absence of these

forces, and with adequate supplies in Nashville, the moment was judged

opportune for an advance."

|

MORGAN'S WEDDING BY JOHN PAUL STRAIN. THIS PAINTING ILLUSTRATES

ONE OF THE MANY SOCIAL EVENTS IN MURFREESBORO AROUND THE HOLIDAYS.

(COURTESY OF NEWMARK PUBLISHING, LOUISVILLE, KY)

|

The moment was not only opportune, it was imperative. Burnside had

been repulsed at Fredericksburg, and William T. Sherman, floundering

about in Chickasaw Bayou above Vicksburg, was about to meet a like fate.

With one army routed and the progress of the other checked, the

administration focused all its dwindling hopes for a victory before the

new year on the Army of the Cumberland.

With so much riding on his offensive, Rosecrans needed sound tactics

and good intelligence. His scouts and spies failed him the latter, and

he formed his plans on the incorrect assumption that Bragg would

organize his defense around Stewart's Creek, a narrow, steep-banked

stream that flowed under both the macadamized Murfreesboro Pike

(Nashville Turnpike) and the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad before

joining Stones River 15 miles northwest of Murfreesboro.

Rosecrans presented his gathered lieutenants with the plan that he

and Thomas had fashioned. The army was to move at first light along

three routes toward three separate objectives, that of the right wing

being most distant. McCook would march along the Nolensville Pike to

Triune, 28 miles away, where Rosecrans erroneously placed the majority

of Hardee's corps. Meanwhile, Thomas would march within supporting

distance of McCook's right along the Franklin and Wilson pikes,

threatening Hardee's left as he moved, then turn east onto the Old

Liberty road and march to Nolensville, 13 miles north of Triune.

Rosecrans assigned Crittenden the direct route to Murfreesboro,

instructing him to move along the Murfreesboro Pike as far as La Vergne.

Stanley divided his cavalry into three columns to screen the infantry:

Colonel John Kennett was to precede Crittenden along the Murfreesboro

Pike; Colonel Lewis Zahm's troopers were to ride ahead of Thomas,

dislodge a battalion of Rebel cavalry at Franklin, and then move

parallel to and protect the right flank of McCook; Stanley would retain

command of his two-regiment reserve and screen the movement of the right

wing along the Nolensville Pike.

|

BRAGG'S MURFREESBORO HEADQUARTERS. (LOSSING'S CIVIL WAR AMERICA)

|

Rosecrans had originally scheduled the movement for December 24, only

to postpone it for a lack of forage. However, one unit did move that

day. Brigadier General James Negley's division from the center advanced

eight miles to Brentwood, secured it, then pushed unopposed another

three miles down the Wilson and Franklin pikes before bivouacking.

This activity did not go unnoticed at Murfreesboro. By Christmas

night it was evident that some sort of Federal movement was imminent.

Satisfied with his dispositions, Bragg took no action, and nightfall

found the army aligned as it had been since the first week of December.

Polk's corps and three brigades of Breckinridge's division rested in

winter quarters around Murfreesboro. At his headquarters near

Eagleville, Hardee had with him the division of Pat Cleburne and

Brigadier General Dan Adams's brigade on detached service from

Breckinridge's division. Brigadier General S. A. N. Wood's small brigade

remained at Triune, providing infantry support to the cavalry operating

in the area. Brigadier General George Maney's Tennessee brigade had been

detached from Polk's corps for similar duty along Stewart's Creek, as

was Colonel J. Q. Loomis's brigade near Las Casas. The cavalry was

spread across the entire army front; all approaches were screened to

within ten miles of Nashville. On the left, Brigadier General John

Wharton had picket lines extended southwest across the Old Liberty road

from Nolensville to Franklin. To his right, Wheeler's brigade,

bivouacked along Stewart's Creek astride the Murfreesboro Pike, covered

the direct approaches to Murfreesboro. John Pegram patrolled the army's

right flank northwest of town, screening the approaches from

Lebanon.

As Christmas drew to a close, patrols from the three Southern cavalry

brigades sat quietly among the dark cedar glades along the road leading

from Nashville, alert to any indication of movement. They would not have

long to wait.

|

|