|

TO MURFREESBORO

The clear skies and warm breezes that for two weeks had lifted the

spirits of both armies ended on December 26. The morning opened

ominously. Chill gusts swirled through the camp around Nashville.

Low-hanging black clouds promised a winter storm. Union soldiers awoke

to see a thick curtain of mist draw across their line of march; by the

time they doused their breakfast fires, a driving rain had set in,

accompanied by a harsh wind that blew steadily from the west.

At his camp five miles south of Nashville, McCook received the order

to advance at 4:30 A.M. Ninety minutes later his lead division under

Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis filed onto the Edmundson Pike.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

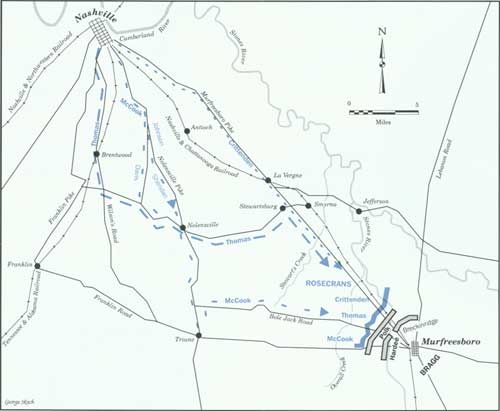

UNION ARMY ADVANCES ON MURFREESBORO

On December 26, 1862, General

William Rosecrans ordered his army to march out of Nashville. Three

wings under Generals McCook, Thomas, and Crittenden slogged over muddy

roads to meet the Confederates commanded by General Braxton Bragg. By

nightfall December 30, both armies were poised outside Murfreesboro.

Each planned to attack the following morning.

|

From the start, Rosecrans's Achilles heel—his cavalry—was

threatening to disrupt his plans. While the infantry slogged forward,

Stanley's reserve cavalry was still breaking camp in the rear, thus

forcing Davis to use his own small mounted escort, Company K of the

Fifteenth Illinois Cavalry, to screen his movement. They did their job

well, uncovering an outpost belonging to Wharton's cavalry brigade five

miles northwest of Nolensville. The Illinoisans chased the Rebels to

the outskirts of town, where they discovered the remainder of Wharton's

troopers dismounted in line of battle.

|

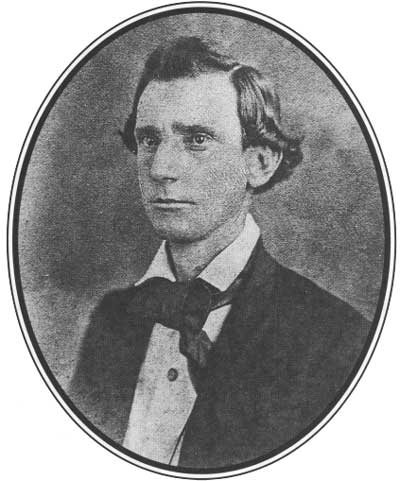

COLONEL JOHN A. WHARTON (LC)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL ALEXANDER MCCOOK AND STAFF. (USAMHI)

|

Davis arrived with the infantry as the rain subsided and deployed his

muddied soldiers into line. But Wharton's orders were simply to impede

the Federal advance by forcing them to deploy repeatedly, and so, his

mission accomplished, he retired through Nolensville before Davis could

send forward his division. Wharton chose as his second delaying position

Knob Gap, a rocky defile that commanded the road to Triune. Under the

cover of a two-gun barrage, Davis deployed again. This time he caught

the Rebels napping. As Davis's men crested the surrounding hills,

Wharton's troopers fled to Triune, less two guns lost to the charging

Federals. It was now nearly dark, and Davis ordered his exhausted men to

make camp by the roadside.

McCook's other divisions had a less eventful day. Brigadier General

Philip Sheridan's column, with Richard Johnson's division trailing,

encountered only light resistance from scattered cavalry outposts. They

bivouacked outside Nolensville shortly after Davis seized Knob Gap.

To the west, Thomas's advance had gone unopposed. Like McCook, he was

ill-served by the cavalry, which failed to break camp on time, and he

advanced without a screen. His objective for the day was Owen's Store,

just south of Brentwood on the Nolensville Pike. Negley, in the lead,

reached it easily. When he caught the sound of gunfire rolling westward

from Davis's fight, he pressed on without orders to Nolensville.

Arriving to find the fighting over, Negley bivouacked his division

alongside those of Sheridan and Johnson. Major General Lovell Rousseau's

division, unable to follow Negley because the country lane to

Nolensville had deteriorated to "the consistency of cream," went into

camp as planned at Owen's Store.

|

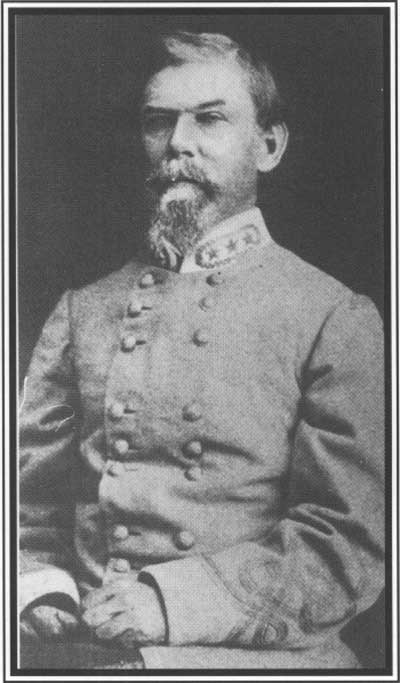

LIEUTENANT GENERAL JOSEPH WHEELER (USAMHI)

|

On the left, the cavalry gave a better account of itself. They

screened Crittenden's infantry and surprised an outpost of Wheeler's

troopers 11 miles out on the Murfreesboro Pike. The incident astonished

Wheeler: it was the first inkling he had of a Federal advance, and the

enemy was only two miles from his La Vergne headquarters. Wheeler

hurriedly brought up his brigade and formed a dismounted line of battle

along Hurricane Creek, a narrow stream that crossed the pike northwest

of La Vergne. The Yankee cavalry deployed on the opposite bank to await

the arrival of Crittenden's lead division under Brigadier General John

Palmer.

Palmer came up at twilight. Anxious to strike a blow before

nightfall, he threw the first regiments to arrive over the creek.

Outnumbered and demoralized, Wheeler's cavalrymen remounted and fell

back into La Vergne. Palmer called a halt on the east bank, his division

just 16 miles from Murfreesboro.

It was now dark. From Hurricane Creek to Franklin, weary, muddied

bluecoats gathered around campfires, cooked supper, then struck out in

search of a dry spot on which to sleep, no easy matter as rain began to

fall again at midnight.

|

It was now dark. From Hurricane Creek to Franklin, weary, muddied

bluecoats gathered around campfires, cooked supper, then struck out in

search of a dry spot on which to sleep, no easy matter as rain began to

fall again at midnight—a fine, chilling drizzle that continued

until dawn. Rosecrans and his staff, meanwhile, made ready for the next

day. Orders were transmitted to Thomas, directing him to move Negley to

Stewartsboro and Rousseau to Nolensville. Crittenden was instructed to

advance on Stewart's Creek; should the enemy retire toward Murfreesboro,

McCook and Thomas would join him there. Rosecrans directed McCook to

march on Triune and press Hardee, whom McCook incorrectly assumed was

there with his whole corps.

Hampered by poor intelligence, Bragg passed an exasperating night.

His cavalry had failed to develop fully the nature of the Federal

advance during the day, and it was well after dark before Wheeler

deduced from prisoners' statements that the Federal army was engaged in

a general forward movement and 9:30 P.M. before this information reached

army headquarters.

The swiftness of the Federal advance surprised and troubled Bragg.

Crittenden, outside La Vergne, was eight miles nearer than Hardee, 24

miles away via the Salem Pike. Despite the need for action, Bragg was

reluctant to order a concentration at Murfreesboro until the Federal

objective had been ascertained. Fairly sure, however, that the principal

threat lay west of Stones River, he directed McCown to march at once to

Murfreesboro. As the success of a concentration at Murfreesboro, should

it be necessary, would depend largely on the cavalry's ability to

conduct an effective delay, Bragg pointedly asked his chief of cavalry

how long he could hold the enemy on the roads. Four days, replied

Wheeler. His fears calmed, Bragg wired Hardee to be ready to abandon

Eagleville and march to Murfreesboro at a moment's notice.

|

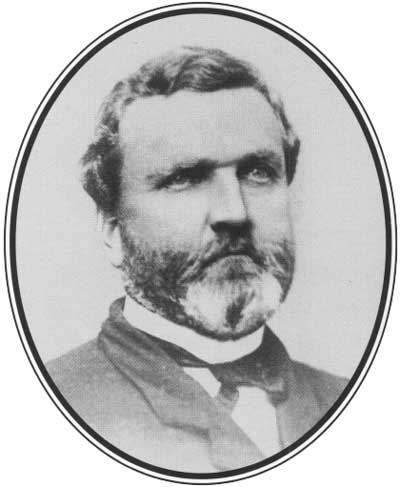

LIEUTENANT GENERAL WILLIAM J. HARDEE (USAMHI)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE H. THOMAS

|

Hardee too had been anxious for information and to get it had sent a

staff officer out on a personal reconnaissance toward Nolensville after

dark. The officer confirmed that the Federals were there in force, and

Hardee wired the news to Bragg. His telegram convinced Bragg that the

time had come to gather the army at Murfreesboro. Shortly before dawn,

movement orders were issued, and Bragg awaited the arrival of his

scattered units.

Saturday, December 27, was a miserable day. Another winter storm

rolled in with cooler temperatures and more rain, preceded by a dense

blanket of morning fog that hampered the Federal advance and allowed the

Rebels to slip away toward Murfreesboro largely unmolested. Observing

the sky that morning, Rosecrans remarked "Not much progress today, I

fear."

He was right. It was 4:00 P.M. before McCook got his lead elements

across Nelson's Creek, a mile and a half north of Triune, just in time

to exchange a few volleys with departing Confederate cavalrymen.

McCook chose not to pursue. Night was coming on and the temperature

falling; a fine sheet of ice had begun to form on the muddy pike, making

the footing hazardous for the already exhausted Federals. Johnson

camped a mile south of Triune, Sheridan in town, and Davis a mile to the

north.

Thomas's divisions, meanwhile, had passed a frustrating day slogging

over what to many must have seemed the worst roads in Tennessee. It took

Negley nearly the entire afternoon to cover the five miles between

Nolensville and Stewartsboro, and his men reached the latter town only

in time to bivouac for the night on Crittenden's right rear. Rousseau

had an even harder march; with cannon and limbers mired up to the hubs,

his division did not enter Nolensville until nightfall.

|

CONFEDERATE CAVALRYMEN ATTACK A UNION SUPPLY TRAIN. PAINTING BY WILLIAM

TRAVIS. (COURTESY OF SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION)

|

On the Murfreesboro Pike, at least, the weather proved more

cooperative. Although a drenching rain fell throughout the day, the fog

lifted early, allowing Crittenden to start shortly before noon. His

objective was to take intact the bridge over Stewart's Creek. The

mission fell to Brigadier General Thomas Wood's division, which covered

the five miles from Lavergne to the creek so quickly that Wheeler's

pickets on the north bank barely had time to make their escape. They set

the bridge ablaze, but the dampening rain and quick action of Wood's

infantrymen, who braved a hail of bullets to toss burning logs and

debris into the water, saved the structure.

Wheeler's cavalry, having been hurled into precipitate retreat all

along the line, regrouped at nightfall south of Stewart's Creek with

George Maney's infantry brigade, a mere ten miles from Murfreesboro.

Wheeler's mediocre performance fed the anxiety at army headquarters.

Wiring Joe Johnston that night, Bragg could only say that Rosecrans was

advancing in strength and that all available troops should be sped to

the Army of Tennessee to oppose him. With his subordinates, however,

Bragg displayed more confidence. In a letter to Cheatham and Withers,

he expressed his belief that Rosecrans's objective was Murfreesboro. In

truth, Bragg could ill afford to harbor doubts, having committed his

army to a defense along Stones River. As the sun set on December 27, all

Confederate units except those detailed to delay the Federal advance

were at Murfreesboro, awaiting orders. They came at 9:00 P.M., in a memorandum

that began as follows: "The line of battle will be in front of

Murfreesborough [sic]; half of the army, left wing, in front of

Stone's River; right wing in rear of the river. Polk's corps will form

left wing; Hardee's corps, right wing. . . . McCown's division to form

reserve, opposite center." Polk and Hardee were to form "two lines from

800 to 1,000 yards apart, according to the ground," and the cavalry was

"to fall back gradually before enemy, reporting by couriers every hour.

When near our lines, Wheeler will move to the right and Wharton to the

left, to cover and protect our flanks . . . Pegram to fall to the rear .

. . as a reserve."

Criticism of Bragg's line of defense came almost immediately. Hardee,

in particular, considered the ground peculiarly unsuited to the

defense: "The open fields beyond town are fringed with dense cedar

brakes, offering excellent shelter for approaching infantry, and are

almost impervious to artillery. The country on every side is entirely

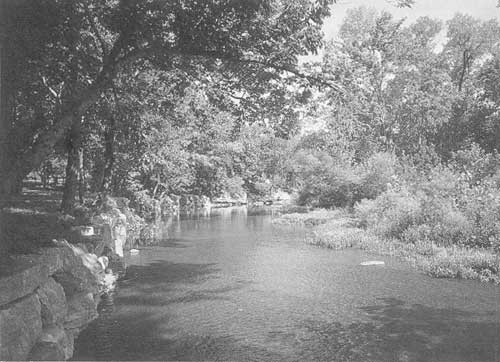

open, and . . . accessible to the enemy." Moreover, Stones River could

be crossed anywhere, he argued—at the usual fords, the water was no

more than ankle deep. The greatest danger, however, lay not in the then

low level of the river—which already was rising with the recent

rains—but rather in how quickly it might swell to an "impassable

torrent" during a violent storm. If that occurred, Hardee warned,

Bragg's two wings would be isolated from each other on opposite sides of

the river.

|

STONES RIVER (NPS)

|

Hardee's assertions were well-founded. Bragg did not know the ground

his army was committed to defend. For instance, 600 yards beyond

Breckinridge's assigned position on the east bank of Stones River lay a

commanding prominence called Wayne's Hill. From it artillery batteries

could enfilade Polk's right on the west bank. Its importance to the

Confederate defense should have been obvious, yet Bragg made no

provision for its occupation.

Bragg's troops marched out to their designated positions on Sunday

morning, December 28. Their movements were unchallenged, thanks to

Rosecrans's characteristic reluctance to conduct military operations on

the Sabbath. In deciding that December 28 was to be a day of rest,

Rosecrans was moved by both operational and theological

considerations—as the army was exhausted from two days' marching and

skirmishing, he deemed it wiser to do battle later with a well-rested

force than to press forward with a blown one.

But the past two days had not developed the situation sufficiently

for Rosecrans to feel confident of Bragg's intentions. The display of

force along Stewart's Creek on the one hand suggested that Bragg might

choose to make a stand along the south bank and contest the Federal

advance on Murfreesboro; on the other hand, it would be to Bragg's

advantage to defend nearer Shelbyville, thought Rosecrans, thereby

drawing the Union army farther from its base at Nashville and rendering

its supply lines vulnerable to attack.

|

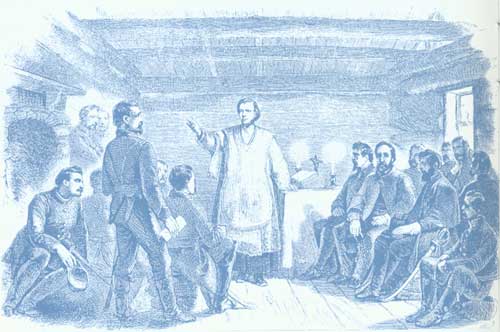

ROSECRANS AND MEMBERS OF HIS STAFF ATTEND MASS IN THEIR STONES RIVER

HEADQUARTERS. (FROM ANNALS OF THE ARMY OF THE CUMBERLAND

|

The first step to unraveling Bragg's plans was to find out where

Hardee had gone the day before. If he had retired to Shelbyville, it

could be assumed that Bragg was abandoning Murfreesboro to draw out

Rosecrans; if he had marched to Murfreesboro, the Confederate line of

battle might be expected to lie somewhere between that town and

Stewart's Creek.

Rosecrans assigned the task to McCook, who in turn sent out Captain

Horace Fisher of his staff with August Willich's brigade to trace the

route of Hardee's withdrawal. By noon, Fisher had surmised from captured

stragglers that Hardee's destination was Murfreesboro.

Rosecrans prepared for battle along Stewart's Creek. He inspected

Crittenden's lines that afternoon, then issued orders to bring the army

together. Thomas was to send Rousseau from Nolensville to Stewart's

Creek by nightfall and McCook was to advance on Murfreesboro by way of

the Franklin road on Monday morning. As darkness fell, Crittenden's

infantrymen lay down to rest on their arms, fully expecting that the

morning would dawn red with bloodshed.

|

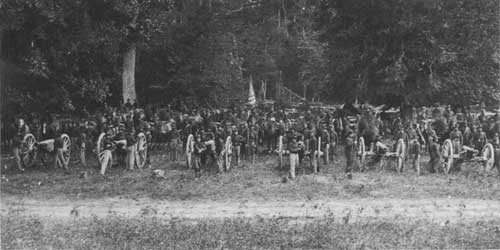

BRIDGE'S BATTERY OF THE ILLINOIS LIGHT ARTILLERY PHOTOGRAPHED IN CAMP

NEAR MURFREESBORO. (COURTESY OF THE WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY,

CLEVELAND, OHIO)

|

|

|