|

THE RIGHT REDEEMED

The muffled, faraway rattle of gunfire greeted the men of the left

wing as they prepared to wade Stones River. At first, no one attached

any importance to the clatter: after all, McCook had been fighting his

way into position since the day before, and the plan of battle called

for him to receive the attack of the enemy. Confident that McCook could

contain the Rebels, Crittenden told Van Cleve to begin crossing his

division as ordered at 7:00 A.M. Samuel Beatty forded his brigade

without incident and deployed on the east bank. Colonel Samuel Price

followed. But as Colonel James Fyffe waited his turn and Brigadier

General Milo Hascall herded his regiments into column, the firing drew

nearer and heavier. The crossing continued, but now "the most terrible

state of suspense pervaded the entire left, as it became more and more

evident that the right was being driven rapidly back on us," said

Hascall.

|

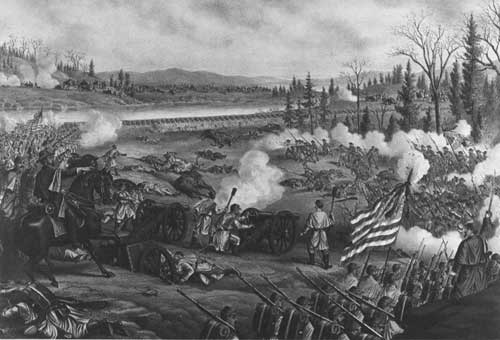

LITHOGRAPH DEPICTS GENERAL ROSECRANS DIRECTING BATTLE AGAINST A

CONFEDERATE CHARGE. (LC)

|

Confirmation of the disaster on the right threw Rosecrans into one of

his famed fits of nervous hyperactivity. He would remain this way until

dusk, and from his agitation came a flood of orders; far too many,

thought Sheridan, for troops struggling to survive to obey. Rosecrans

directed brigades, regiments, companies—any body of men he could

admonish into his ragtag line. Sometimes his orders countermanded the

efforts of subordinates trying to piece together their units.

Rosecrans's frenzy overcame his better judgment. He rode repeatedly to

the muzzles of his front-line units and often beyond. But whatever the

wisdom of a commanding general exposing himself to direct brigades and

regiments, it must be conceded that, at a moment of supreme crisis,

Rosecrans's presence helped restore the morale of the soldiers who saw

him.

Fortunately for the army, Rosecrans issued several timely commands

before succumbing to his anxiety, orders second only to Sheridan's stand

in their impact on the outcome of the battle.

Thomas received the first order. Through him, Rosecrans directed

Rousseau's three brigades, then bivouacked midway between army

headquarters and the Round Forest, into the cedars to sustain Sheridan's

exposed right. Next, he commanded Crittenden to suspend Van Cleve's

crossing and deploy Price behind McFadden's Ford while holding Fyffe and

Sam Beatty in reserve along the railroad.

|

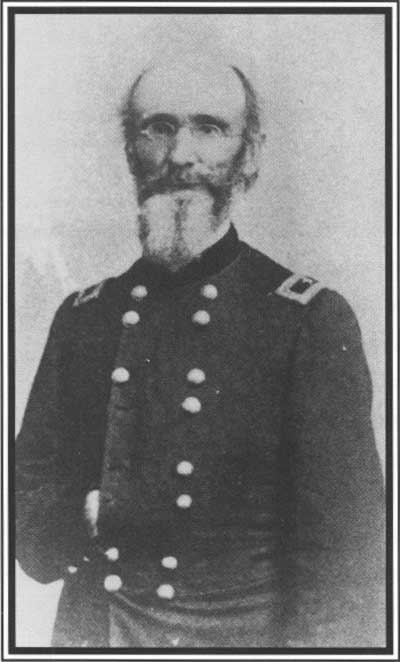

BRIGADIER GENERAL HORATIO VAN CLEVE (USAMHI)

|

No sooner had Rosecrans issued these instructions than a rabble of

dazed infantry stumbled from the timber west of the turnpike. With the

collapse of McCook now painfully apparent, Rosecrans abandoned hope of

retaining a reserve and instead mustered every available unit to piece

together a new front. Van Cleve's wet and shivering infantry, tramping

toward the railroad, suddenly found themselves running into the cedars

to extend Rousseau's right, and Hascall's idle brigade received orders

to march up the turnpike as far as army headquarters, then turn to the

southwest and press forward with Van Cleve. The ever-present Rosecrans

issued Harker similar instructions in person.

Beatty, Fyffe, and Harker swung north through a growing throng of

wagons and demoralized troops. Despite the congestion, they eventually

reached their destination. Not so Hascall. Starting last, his men found

the way blocked after moving just 200 yards. Unable to continue, Hascall

placed his brigade in reserve behind the Round Forest—a wise

decision, as his command would prove indispensable in repelling a series

of afternoon assaults against the wooded salient.

Rosecrans's next decision was his best of the day. Aware that his

patchwork line could not hold indefinitely and that a Confederate drive

against the turnpike itself was likely, he placed St. Clair Morton's

Pioneer Brigade and Stokes's Chicago Board of Trade Battery on a

commanding rise near army headquarters. From there, the Chicagoans could

train their cannon on any Rebels trying to cross the 800 yards of open

ground between the eastern edge of the cedars and the turnpike.

|

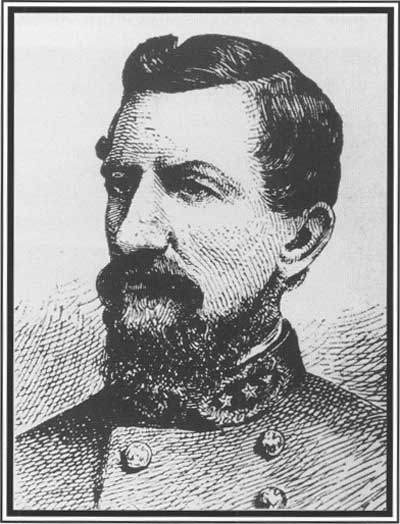

BRIGADIER GENERAL ALEXANDER STEWART (USAMHI)

|

Meanwhile, to the west, Rousseau's division joined Sheridan's right

in good order at 9:30 A.M. Skirmishers disappeared into the cedars,

fallen trees became breastworks, and blue forms scrambled for cover as

the Confederates, only a few hundred yards away, closed rapidly.

The Rebels were showing signs of life on Sheridan's front as well.

His first attack having accomplished nothing, Patton Anderson called

upon Brigadier General Alexander Stewart to detach two regiments to

support a second run at the Yankees. Stewart refused. An officer of rare

promise, Stewart had no intention of repeating Anderson's mistake of

throwing in his regiments singly; after conferring with Withers, he

chose to throw his entire brigade simultaneously against the

Federals.

Stewart's thoughtful decision spelled the end of Sheridan's

stronghold. Within minutes of his assault Roberts was dead and Captain

Houghtalling was severely wounded.

|

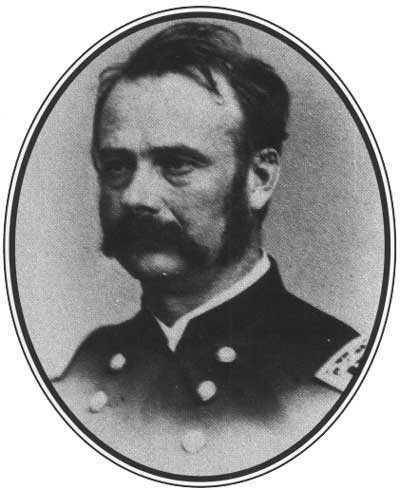

MAJOR GENERAL LOVELL H. ROUSSEAU (USAMHI)

|

The Federals may have overcome the loss of officers, but they could

not fight without cartridges. "There was no sign of faltering with the

men," Sheridan later boasted, "the only cry being for more ammunition,

which unfortunately could not be supplied." And as it could not be

supplied, Sheridan prepared to retire.

From across the field northwest of the Harding house, Maney and

Manigault watched the bluecoats fade into the timber north of the

Wilkinson Pike and moved cautiously forward. By the time they reached

the pike, the fighting was over. Meddling again in the affairs of

Sheridan, McCook had reappeared long enough to order Greusel to break

contact and fall back to the Nashville Turnpike. Greusel's ill-timed

withdrawal—made without Sheridan's knowledge—allowed Lucius

Polk to overrun and capture all six guns of Houghtalling's battery and

two of Bush's. After covering the retreat of Roberts's brigade and the

remainder of the division artillery, Schaefer broke contact at 10:45

A.M. and turned northward.

With Sheridan at last defeated, Hardee turned his attention to the

Nashville Turnpike and the Union rear, blocked only by Rousseau's now

isolated division. The task of removing Rousseau fell to McCown, whose

units were resting near the Gresham house. As Rains's brigade had

suffered the fewest casualties, McCown moved it from the division left

to the right with orders to take Rousseau from in front while Ector and

Harper drove past Rousseau's right flank toward the turnpike.

McCown's plan for gaining the Union rear, simple in design and seemingly

foolproof, failed to allow for the generalship of Rousseau, a

citizen soldier of the first degree. Even before the blow fell, Rousseau

realized that he could not hope to hold out alone. As the scattered

popping of rifle fire announced the approach of Rains's skirmishers, he

rode off in search of a fall-back position. Encountering Battery A, 1st

Michigan Artillery, as it struggled over limestone outcrops behind

Benjamin Scribner's brigade, Rousseau told Lieutenant George Van Pelt to

turn the limbers around and find firing positions near the turnpike.

Lieutenant Alfred Pirtle, Rousseau's ordnance officer, helped Rousseau

place the guns.

Rousseau returned to the front to find his line already engaged.

Nonetheless, he was able to extricate Oliver Shepherd's Regular Brigade

and Scribner's command and deploy them along high ground beside the

turnpike, near Van Pelt's battery, which was joined by Lieutenant

Francis Guenther's Battery H, 5th United States Artillery.

Unfortunately, Rousseau apparently neglected to pass the word to his

third brigade, and John Beatty remained in the cedars, nearly surrounded

by the better part of a Confederate division without knowing he fought

alone. Beatty had last seen his division commander at 9:00, when

Rousseau enjoined him to hold his line "until hell freezes over."

|

ILLUSTRATION BY A. E. MATHEWS OF GENERAL SAMUEL BEATTY'S BRIGAGE

ADVANCING TO SUSTAIN THE UNION RIGHT. (LC)

|

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL JAMES E. RAINS (BL)

|

Lucius Polk ran into Beatty first, and the Ohioan repulsed him. A

lull followed, and Beatty, who had noted the absence of firing from

beyond his flanks during the fight, sent staff officers to search for

the rest of the division. They all returned to report no one left on the

field but their own brigade and Rebels. "I conclude that the

contingency to which General Rousseau referred—that is to say, that

hell has frozen over and about face my brigade and march to the

rear."

He was right. Polk chose precisely the moment of Beatty's withdrawal

to renew his assault. Vaughan's brigade, ordered to his support by

Cheatham, joined Polk on his right. And Wood may have fallen in on his

left, though reports are unclear on this point. In any case, the

pressure was enough to panic the Federals, and despite Beatty's efforts

at rallying them for a final stand at the edge of the cedar brake, they

swept into and through the cotton field toward the turnpike.

Hardee now had cleared all Federal forces from the thicket north of

the Wilkinson Pike. Only two regiments of Colonel William Grose's

brigade stood between Rains and the turnpike. Rains charged the

midwesterners, driving them pell-mell through the timber.

|

MAJOR GENERAL DAVID STANLEY (USAMHI)

|

Grose's winded infantrymen cleared Rousseau's batteries and

collapsed. For a moment there was silence, then Rains's hollering and

leaping Rebels spilled out of the woods. At that instant the batteries

roared into action, and the cotton field was blanketed in smoke. Rains

had stumbled into a hornet's nest. Van Pelt, Guenther, and a third

battery under Captain Charles Parsons joined in decimating the exposed

Confederates. Their infantry supports contributed volleys. Rains fell

with a bullet through his heart. His men held on ten minutes

until—hungry exhausted, and leaderless—they melted away.

As the survivors stumbled rearward, they encountered the equally

tired men of Cleburne's division and learned why they had charged the

turnpike alone. After rolling up Beatty, Cleburne had discovered a large

body of Yankees beyond his right. Rather than expose his jaded infantry

to a flanking fire that might break them, Cleburne pulled Johnson and

Polk out of the cedars. After giving Johnson time to regroup, Cleburne

ordered him to make contact with Liddell, who by then had drifted a mile

to the northwest. Johnson found Liddell south of the Widow Burris house.

Liddell yielded him the front. Vaughan, still under orders to support

Cleburne, and Polk fell in on Johnson's right. Liddell rejoined

Johnson's left, and Cleburne again sent his command forward, this time

toward the Widow Burris house and the Nashville Turnpike beyond. Wood

stayed in the rear to guard the corps ordnance train.

The troops that had convinced Cleburne to change course belonged to

Colonel Timothy Stanley. For twenty minutes following Sheridan's

departure, Stanley's front was quiet. Then Stewart and Anderson,

supported by a barrage from four batteries, slammed into his line. The

only instance of effective artillery support provided Rebel infantry

during the battle, it shattered Stanley's brigade. Flanked

simultaneously by Manigault and Maney, Stanley's command dissolved.

The defeat of Stanley brought the battle to Colonel John Miller,

commander of the second of Negley's two brigades. Having just heard

Negley's plea to "hold my position to the last extremity," Miller

scrambled to realign his brigade to face the enemy. Unfortunately, they

struck before he could move. Stewart lapped Miller"s right while

Anderson maintained pressure in front. Miller's men held on until their

ammunition began to run out. Miller let them fall back. With Stanley

gone and Stewart now behind him, retreat was inevitable.

It was noon. Six hours earlier a double line of blue had extended

from Stones River to the Franklin road. Now only a tangled remnant

remained to receive the eleven butternut brigades approaching the

Nashville Turnpike. Should any of them sever that vital artery, it might

cost Rosecrans the battle and, conceivably, much of his army.

Rains had lunged at the turnpike alone and met with disaster.

Undaunted, Ector was about to repeat that error. His failure to support

Rains had doomed that attack; now Harper's inability to keep pace with

Ector was to have the same result. McCown either was unaware that the

two brigades had separated or was unable to reunite them, and Ector's

men stepped out of the cedars alone. They could not have struck a

better-prepared segment of the Union line had Rosecrans guided them in

himself. The units facing Ector were virtually the only fresh troops

left to Rosecrans. Directly opposite the Texans lay Morton's Pioneers,

Stokes's Battery, and Battery B, Twenty-sixth Pennsylvania Light

Artillery. And in a cedar glade beyond Ector's left, Sam Beatty's as yet

uncommitted brigade paused to enfilade the Rebel flank.

|

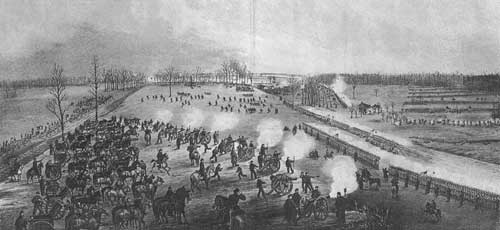

A. E. MATHEWS LITHOGRAPH OF THE FIGHTING OF PALMER'S AND ROUSSEAU'S

DIVISIONS. (LC)

|

Ector's Texans lasted a bit longer in the cotton field than had

Rains's men, but their gallantry got them only more dead and

wounded.

Ector fell back, and Sam Beatty resumed his march. He was joined on

his right by Fyffe, who took position near the Asbury Church at 1:00

P.M. Harker arrived a few minutes later to extend the line northward to

the Widow Burris house. There Van Cleve halted them. Minutes later,

Cleburne's division poured forth from the woods to their front. "We

received such a Southern greeting as we had never before experienced,

not even in the bloody forest of Shiloh," remembered a member of Fyffe's

staff. Cleburne's line engulfed Van Cleve and Harker, and the fight was

short.

Rosecrans was at the timber's edge near the turnpike, redeploying Van

Cleve's and Harker's regiments as they spilled over the field. At that

moment, Colonel Luther Bradley appeared with a fragment of Roberts's

brigade in search of ammunition after their long ordeal in the cedars

that morning. Rosecrans diverted him into their line; to Bradley's

protest that he needed cartridges, Rosecrans replied that it was a

desperate moment and they must go forward, with or without

ammunition.

The situation at 3:00 P.M. appeared desperate indeed. As the sun sank

beneath the horizon and the chill of a winter's eve set in, Cleburne's

seemingly invincible veterans drove toward the Nashville Turnpike and

the Union rear. Cleburne's lieutenants were confident of success. So

certain was Liddell of the outcome that he paused at the Widow Burris

house to chat with Union surgeons. Suddenly, recalled Liddell, the

unbelievable happened: "While this was occurring, which was in an

incredibly short space of time, I discovered our lines breaking rapidly

to the rear, not knowing what was the cause of this sudden movement."

Bushrod Johnson too was dumfounded: "At the moment in which I felt the

utmost confidence in the success of our arms I was almost run over by

our retreating troops."

|

A DIORAMA SCENE AT STONES RIVER NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD SHOWS CONFEDERATE

CHARGE. (NPS)

|

What had gone wrong? Why did Cleburne's division crack just as it

reached its final objective? Cleburn himself offered the best

explanation: Simple exhaustion and not Yankee bullets had turned the

tide.

|

What had gone wrong? Why did Cleburne's division crack just as it

reached its final objective? Cleburne himself offered the best

explanation: Simple exhaustion and not Yankee bullets had turned the

tide. Afterward, Hardee would complain of the absence of reinforcements

at this, the crucial moment of the battle. The time Cleburne expended in

breaking off the pursuit of Rousseau and regrouping prior to attack

Harker and Van Cleve had been excessive but, without fresh units to

replace him, unavoidable, reasoned Hardee. It was this delay, he

believed, that allowed Rosecrans to patch together a final defensive

line near the turnpike.

Hardee's criticism is justified. To several requests for

reinforcements, Bragg responded that none were available. By 3:00 P.M.

this was true—Bragg had committed them in a reckless attempt to

break the Union salient that had developed around a small copse along

the railroad. For four hours this little wood obsessed Bragg, and his

obsession cost him the battle.

|

|