|

COLLAPSE OF THE UNION RIGHT

Morning came. The darkness melted into a cold, gray mist that

dampened the air and depressed the senses. At 5:00 A.M., Johnson's

division was quietly awakened, and 6,200 drowsy, shivering infantrymen

rose from the frozen ground to build their breakfast fires. Huddled in

small groups, the men sipped coffee and discussed the chances of battle

being joined before the day's end. Officers handled their units as

though they were a reserve posted safely in the rear, rather than a

dangerously exposed army flank resting within 700 yards of the enemy. As

the minutes passed and the silence remained unbroken, the sense of peril

actually diminished. Unable to find water during the night, the

commander of Battery E, 1st Ohio, released half his horses 500 yards to the

rear at daylight to a recently discovered stream. At his campsite,

McCook enjoyed a leisurely shave.

Out on the picket lime all was quiet.

Perched atop split-rail fences or reclining against cedars, the

sentinels gazed absently into the twilight. And then, at 6:22 A.M., they

saw it.

|

Out on the picket line all was quiet. Perched atop split-rail fences

or reclining against cedars, the sentinels gazed absently into the

twilight. And then, at 6:22 A.M., they saw it.

Emerging from the gray fog was a wall of butternut: 4,400 men of

McCown's division arrayed in a long double line with the division of Pat

Cleburne trailing 500 yards to the rear.

Rising at the first hint of dawn, they had formed ranks quietly and

without breakfast. A nervous tension gripped the men. Two days of

inactivity, of lying still in the cold and dampness, had taxed their

patience to the limit. Any movement was welcome.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE CONFEDERATE ATTACK BEGINS THE BATTLE OF STONES RIVER

At dawn on December 31, 1862, Hardee's Corps of Confederates surprised the Union

right at breakfast and drove McCook's troops back nearly a mile by 8

A.M. Rosecrans canceled the planned Union attack on the Confederate

right and sent reinforcements to shore up McCook when news of the setback

reached him.

|

On they came with deliberate steps. Brigadier General James Rains's

brigade occupied the left, the dismounted Texas cavalrymen of M. D.

Ector held the center, and Evander McNair's Arkansans were on the right.

A spattering of musketry finally rattled from the dazed Union picket

line, startling Willich and Johnson, who had been talking at division

headquarters, but drawing no response from the advancing Confederate

wave, now within 200 yards of Kirk's lines. After frantically calling

back his horses, Edgarton opened on Ector with a salvo of canister. With

that the Texan ordered his men forward at the double quick, and the

Union picket line disintegrated.

Five minutes later, Kirk's line crumbled. Kirk fell, struck in the

thigh by a minie ball. Brigade command passed to Colonel Joseph Dodge,

but the honor was empty. McNair slammed into his left regiments, Ector

gained his rear, and Dodge ordered a retreat.

With Dodge swept from the field, McCown turned his attention to

Willich's troops, who were no more ready for battle than Kirk's had

been. Although the Confederates were closing on them from the southeast,

four of Willich's five regiments fronted to the west, leaving their

flanks exposed to an oblique attack. It was the collapse of Kirk,

however, that made the defeat of Willich inevitable. Willich may have

been able to offer respectable challenge to McCown's Rebels had it not

been for the refugees from Kirk's shattered regiments streaming through

his lines and obscuring the fields of fire of his infantry.

McCown now had the field, along with eight guns and some 1,000

prisoners. His men continued on after the rapidly scattering remnants of

Johnson's division. There was little organization to the Federal

retreat and no unified command. Regiments—or more often bits of

regiments—made brief stands behind fences or farmhouses.

|

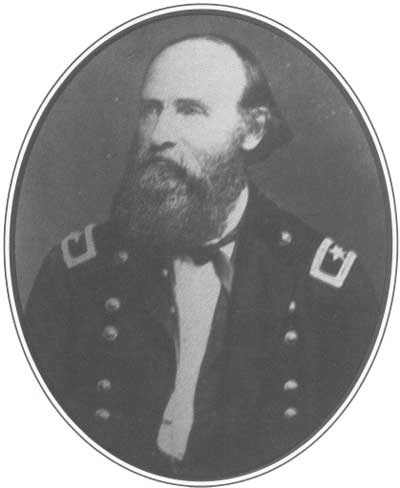

BRIGADIER GENERAL AUGUST WILLICH (USAMHI)

|

|

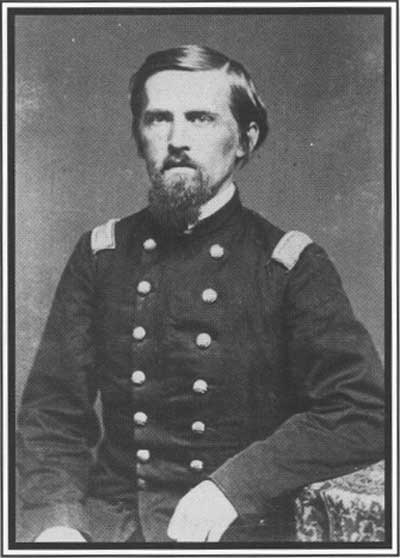

BRIGADIER GENERAL EDWARD N. KIRK (LC)

|

As McCown's Southerners drove the survivors of Kirk's and Willich's

brigades, the Confederate offensive showed its first sign of unraveling.

Although Rosecrans would later censure these units for inclining "too

far to the west" in their retreat, the route the fleeing Federals

spontaneously chose assisted the Union defense by throwing McCown's brigades

off course and slowing Cleburne, who unexpectedly found himself in the

front line. Unable to see through the mist, Cleburne and his brigade

commanders assumed the firing to their front meant that McCown was in

contact ahead of their division; that is, until men began dropping in

the front ranks.

Cleburne had struck Davis's division although at that moment he knew

only that "I was, in reality, the foremost line on this part of the

field, and that McCown's line had unaccountably disappeared from my

front." Cleburne shook out his skirmishers and elected to continue the

right wheel called for in Bragg's plan of battle.

|

MAJOR GENERAL PATRICK R. CLEBURNE (LC)

|

Like Cleburne, Davis found himself in an unexpected position. In

command of what had become the right-flank division of the army, he used

the delay between McCown's attack on Johnson and the appearance of

Cleburne to withdraw Colonel Philip Post's brigade, which had begun the

action on Kirk's left, to a more defensible position facing south toward

the Franklin road a half mile away. Colonel Philemon Baldwin's reserve

brigade of Johnson's division rested 400 yards to Post's right rear.

Bits and pieces of the shattered brigade of Kirk and Willich paused to

extend Baldwin's line.

Scarcely had Post taken position when Bushrod Johnson's brigade

emerged from the woods on either side of Gresham Lane, and the two lines

disappeared in gunsmoke.

While Johnson struggled to dislodge Post, Cleburne's left brigade

under St. John Liddell, advancing northward beyond Johnson's left, found

itself in an equally brutal contest with Baldwin. Here Liddell was

joined by McNair, who had halted in the open fields east of Overall

Creek after losing sight of Rains and Ector, only to find his flank

balanced precariously between Baldwin to his right front and Post to his

right rear.

Crouched behind a split-rail fence, Baldwin's men watched the Rebel

line approach. "The men were good-sized, healthy, and well clothed,"

remembered a Yankee, "but without any attempt at uniformity in color or

cut." At 150 yards, Baldwin's artillery and the 1st Ohio Infantry opened

fire, and Liddell's left recoiled. At 100 yards the 6th Indiana released

its volley, and Liddell's right ground to a halt. The Arkansans fell to

the ground and traded volleys with their Yankee tormentors. Their

plight was desperate. Liddell had struck the Union line unsupported,

McNair having lagged behind on the left.

|

PAINTING BY CIVIL WAR ERA ARTIST WILLIAM TRAVIS ON THE FIRST DAY AT

STONES RIVER. PART OF THE UNION RIGHT FLEES BEFORE MCCOWN'S AND

CLEBURNE'S DIVISION. (SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION)

|

|

COLONEL WILLIAM CARLIN (USAMHI)

|

As Liddell's regiments wavered, McNair belatedly charged the

patchwork lines of Kirk and Willich. McNair's men ran the 300 yards to

the Federal positions, slamming into and knocking down intervening

fences without missing a stride. The defenders scattered long before

McNair's men reached their ragged line. That they did not give a better

account of themselves is hardly surprising in view of the thrashing

they had received an hour earlier; the men simply had lost the will to

resist.

Rather than pursue them, McNair halted and changed front to slash at

the exposed right flank of the 1st Ohio. It collapsed, emboldening

Liddell's Arkansans, who renewed their attack against Baldwin's front

and finally drove the Federals into the timber.

Meanwhile, on the east side of Gresham Lane, Cleburne's remaining

brigades encountered opposition as determined as that which Liddell and

Johnson faced. Moving their brigades smartly into the cedar glade

opposite the Widow Smith house, S. A. M. Wood and Lucius Polk were

confident that McCown had swept the area clean. They were wrong. Lying

undetected behind outcrops and among cedars so dense that company

commanders could not see the length of their lines was the 101st Ohio of

Colonel William Carlin's brigade. The Ohioans waited until Wood's

Confederates were just a few yards away before opening fire. The stunned

Confederates recoiled instinctively.

Polk received an equally warm welcome on entering the cedars. He

had advanced only 700 yards when the colonel of the 5th Tennessee sent

word that the brigade right was engaged. Polk quickly issued orders

bringing his remaining regiments across the Franklin road and into a

right wheel against Carlin's right flank.

But Carlin had foreseen Polk's turning movement. Like Post moments

earlier, Carlin seized the opportunity presented by the brief confusion

in the Rebel ranks to withdraw his units to more tenable positions.

Advancing a second time, Polk and Wood struck Carlin's line together.

The ten year veteran of the regular army began to despair. A heavy

silence beyond his right told him Post had quit the field. Rather than

see his brigade enveloped and destroyed piecemeal, Carlin decided to

withdraw by the left flank. But before he could relay the order he was

unhorsed, then struck by a Rebel bullet, and the retreat he had hoped to

direct began spontaneously.

As they surged forward in pursuit, some among the victorious

Confederates found it impossible to contain their enthusiasm. None was

more ecstatic than young William Matthews, a colorbearer in the 1st

Arkansas for whom Stones River was his first battle. "Boys, this is

fun," he yelled as the Arkansans chased the fleeing Federals. "Stripes,

don't be so quick," advised a veteran, "this is not over; you may get a

ninety-day furlough yet."

Twenty minutes latter, Matthew's exuberance turned to agony as a

bullet shattered his arm.

Five Union brigades were in full retreat, and the battle was hardly

an hour old. Confusion and panic gripped the men, paralyzing what few

efforts were made to resist the Confederate attack west of Gresham Lane.

There was no sign of McCook, nor of Johnson, nor of any leadership

above the brigade level.

|

TRAVIS PAINTING OF MAJOR GENERAL ALEXANDER MCCOOK (CENTER) TRYING TO

RALLY HIS CORPS. (SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION)

|

Near the Gresham house, Post and Carlin struggled to piece together

their shattered commands for a final stand. Despite their pleas, only a

corporal's guard rallied around the colors. East of Gresham Lane, Polk

and Wood rolled over the plowed fields of corn and cotton for a rematch

with Carlin. A severe and unexpected enfilading fire from two artillery

batteries belonging to the division of Phil Sheridan and posted on a

knoll to Wood's right caused him to halt. Polk, who escaped the

shelling, pushed on, his left covered by Bushrod Johnson.

It was the broken ground, more than this last heave of Yankee

resistance, that threatened to disrupt Cleburne's assault. After

disposing of Baldwin, Liddell's Arkansans got lost in the cedar glades

near the pike, veering away from the rest of Cleburne's division toward

the northwest. Like the earlier detours of Rains and Ector, the drifting

of Liddell's brigade demonstrated how quickly the Confederate attack

unraveled amid the patchwork of murky forests, overgrown fields, and

split-rail fences that checkered the battlefield. While Liddell was

losing his way, McCown was at last reuniting his division. Separated

from the remainder of the division and finding both his men and

ammunition nearly spent, McNair had halted along the pike. While his men

refilled their cartridge boxes, McNair, troubled by a persistent illness,

yielded brigade command to Colonel R. W. Harper. As he rode away,

the brigade of Rains and Ector chanced upon his Arkansans. Surprised to

find themselves reunited with Harper, they too stopped to draw

ammunition and send their prisoners to the rear. Delighted to have his

three brigades together again, McCown was content to await orders.

|

|