|

SHERIDAN'S STAND

The first indication Bragg had that his attack was not going as

planned came moments after McCown struck Johnson's picket line. A

courier from Hardee brought word that Cheatham had failed to advance;

consequently, Cleburne's right was exposed. Bragg dispatched a messenger

to Cheatham with a rebuke and an order to get moving. The Tennessean

responded, but Bragg's troubles with him were far from over. Throughout

the day Cheatham acted rashly and recklessly, sacrificing hundreds of

irreplaceable veterans in poorly coordinated charges. Apologists later

attributed the Tennessean's impulsive behavior to his natural

combativeness; critics, however, suggested that Cheatham, like so many

of the men in ranks, was drunk.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE UNION LINE HOLDS

By noon, Rosecrans had reinforced his right,

and Bragg's Confederates repeatedly assaulted the Union center at the

Round Forest. Their line of battle was disrupted by passing around the

Cowan house. Union Colonel Hazen rallied his brigade against these

attacks and by day's end maintained control of "hell's half

acre."

|

Sober or drunk, at 7:00 A.M. Cheatham moved to the attack. Instead of

continuing the right wheel with a general advance of both his

lines—however impractical this tactic ultimately proved—he

committed his division piecemeal, allowing Sheridan to deploy and

redeploy his units so as to repel each attack in turn.

Colonel J. Q. Loomis's brigade opened the action. The odds were

against the Alabamians, and they knew it. Three hundred yards of open

cornfields separated them from Colonel William Woodruff's three Union

regiments (the last elements of Davis's division still intact), which

lay on a ridge behind a fence amid a dense growth of rough cedars.

Loomis's butternuts slogged through the sodden fields, conducting a

right wheel as they neared the enemy. Once within range of the Yankee

rifles, the brigade separated, and both halves were chewed up by

Woodruff's defense and a slashing counterattack by Joshua Sill. Loomis

himself was struck down by a falling limb.

|

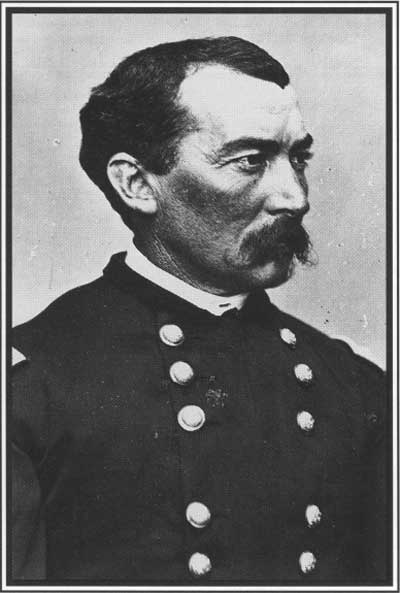

MAJOR GENERAL BENJAMIN FRANKLIN CHEATHAM (USAMHI)

|

|

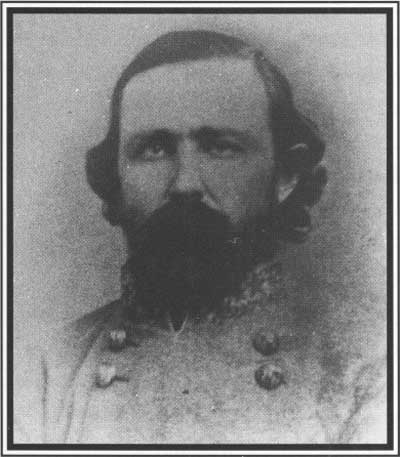

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOSHUA W. SILL (LC)

|

In halting this first Rebel charge the Federals paid a heavy price.

Sill was killed. A bullet had gored his upper lip, passing into his

brain and emerging at the base of the skull. Brigade command passed to

Colonel Nicholas Greusel, who reformed his line and awaited the next

Confederate onslaught, which came just moments later. While Cheatham

reorganized Loomis's shattered brigade, Colonel Alfred Vaughan moved

forward over the same ground.

Vaughan's attack began inauspiciously. With Wood masking its left

and Maney uncomfortably close on its right, the brigade quickly lost its

alignment as it marched up the slippery slope before Woodruff's line.

Nonetheless, the Tennesseans managed to pry two of the three Federal

regiments from the fence, only to be thrown back by a spirited

counterattack. Vaughan regrouped and came on again. Although men fell in

windrows—56 of the 12th Tennessee dropped dead or wounded, and

Leonidas Polk, in this long day of costly charges, would later single

out Vaughan and his troops for special praise—the survivors pressed

on. Woodruff's line crumbled, not to be reformed.

While Woodruff struggled with Vaughan, Greusel faced his first direct

attack. The time was 8:00 A.M. Like Loomis and Vaughan, Cheatham's third

brigade commander, Colonel Arthur Manigault, attacked late and

unsupported. And like them, he saw his brigade chewed up and

repulsed.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL PHILIP SHERIDAN (LC)

|

As Manigault withdrew to the sound of cheering from the Union ranks,

the first of Sheridan's regiments to have been engaged found itself with

empty cartridge boxes. With its commander badly wounded, the 36th

Illinois received permission to retire north of the Wilkinson Pike to

search for ammunition. The Illinoisans found none, but while they

looked, General McCook rode up and waved them back to the Nashville

Turnpike.

This rare appearance of McCook was typical of his actions in the

early hours of the battle. He was as invisible as Sheridan was

ubiquitous. Instead of helping his finest division commander rally

survivors for a stand near the Harding farm, McCook drifted aimlessly

about, stepping in only to order regiments still engaged to retreat, as

if the shock of battle had overcome his own will to resist.

With or without McCook, Sheridan aimed to fight on. While Manigault

prepared to renew the attack, Sheridan reformed his lines to conform to

the second positions of what remained of the brigades of Woodruff,

Carlin, Post, and Baldwin. He withdrew his right-flank regiments to the

Harding farm and arrayed his three batteries—those of Hescock,

Houghtalling, and Bush—between the farmyard and a small neck of

woods 600 yards to the northeast, near Negley's right.

Manigault struck Sheridan's second position at 8:30 A.M. This time he

had support. Cheatham had committed George Maney's brigade, his last.

Maney guided his men across the open ground behind Manigault, but he had

no chance to make his presence felt, as Manigault's brigade crumbled

under a murderous converging fire from Bush and Houghtalling.

Colonnel George Roberts, his brigade as yet unbloodied, saw in

Manigault's stalled attack a chance to swing the momentum of the battle

in favor of the Federals.

|

Colonel George Roberts, his brigade as yet unbloodied, saw in

Manigault's stalled attack a chance to swing the momentum of the battle

in favor of the Federals. Encountering Sheridan behind Hescock's guns,

Roberts begged permission to counterattack. The colonel's enthusiasm

was contagious, and Sheridan immediately approved the plan. Roberts

went forward with his men, waving his cap madly and yelling, "Don't fire

a shot! Drive them with the bayonet!" Manigault's men were too badly

shaken by the artillery fire to resist, and they retreated to their line

of departure.

Manigault falling back met Maney coming up. The two conferred.

Manigault outlined the Federal dispositions, then subjected Maney to an

impassioned account of the havoc Bush and Houghtalling had wrought on

his brigade, explaining that their synchronized, mutually supporting

fire made an attack against just one impossible. Manigault suggested

that they each attack a battery simultaneously. Maney agreed. Manigault

selected Houghtalling's battery; Maney, that of Bush. The two generals

returned to their commands, which had spent the past twenty harrowing

minutes dodging incoming shells. Manigault changed front to the right

so as to face Houghtalling, and Maney advanced to Manigault's left.

|

MEMBERS OF THE WASHINGTON LIGHT ARTILLERY 5TH COMPANY TOOK PART IN THE

LAST CONFEDERATE CHARGE AT STONES RIVER. (PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORY OF THE

CIVIL WAR, VOL. 2)

|

Sheridan, meanwhile, was availing himself of this second lull to

modify his lines. Again it was the failure of the commands on his right

to resist Cleburne and Vaughan that forced him to withdraw. Roberts's

brigade would be the anchor of this, Sheridan's third position. Sheridan

had reeled him into the timber along the Wilkinson Pike after his

successful counterattack. He then sent orders to Schaefer and Greusel to

retire onto Roberts's right. Finally, he moved Hescock's battery out of

range of Rebel sharpshooters to a small knoll in front of Negley's

right.

While Sheridan organized his third position, Maney prepared to seize

Bush's battery and drive off its infantry supports, which had not yet

moved. Supposing Manigault to be ready, Maney sent his Tennesseans

forward. As they right wheeled south of the Brick Kiln, Bush limbered up

and dashed away to join Hescock, their infantry support retiring to the

Wilkinson Pike. Raising a cheer, Maney's men swarmed over the abandoned

ground, where they presented Houghtalling with a shooting-gallery

target.

Houghtalling's shelling froze Maney and his regimental commanders

with indecision; they believed that Manigault had dislodged Houghtalling

and thus assumed the fire to be friendly. But friendly men were dying,

and so, while their leaders hesitated, the soldiers fell to the

ground.

Private Sam Watkins had another explanation for the failure of

Confederate leadership at this critical juncture: "John Barleycorn was

general in chief. Our generals, and colonels, and captains, has kissed

John a little too often. They couldn't see straight."

Whatever the cause of the officers' indecision, it was clear that the

identity of the guns had to be established—and quickly. A staff

officer rode forward and was shot dead. Two regimental colorbearers

stepped into the open and waved their banners. Houghtalling trained his

guns on them and fired. They survived but brought back colors

considerably more tattered.

Convinced at last that Manigault had failed to move as agreed, Maney

brought up Turner's battery, which opened on Houghtalling with "terrible

effect."

While Turner and Houghtalling pounded one another, Vaughan's

Tennesseans emerged from the timber south of the Harding house and

approached Maney's left. Unlike Maney, Vaughan never doubted that the

artillerymen raking his lines were Yankees. Stopping short of Maney's

left, Vaughan wisely ordered his men to take cover while he awaited

instructions from Cheatham.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL GEORGE EARL MANEY (USAMHI)

|

Sheridan now confronted three Confederate brigades from his position

along the Wilkinson Pike—Manigault and Maney opposite Roberts,

Vaughan opposite Schaefer and Greusel. As before, it was not the forces

to his front that troubled Sheridan most, but rather those beyond his

right, where the Union line was again crumbling. This time he decided to

see for himself what was happening to Davis's division. He galloped past

Woodruff to Carlin, who with Davis was struggling to rally his brigade.

A cursory inspection of Carlin's fragile line convinced Sheridan he

would have to draw in his right still further. Retracing his route,

what Sheridan saw as he passed Woodruff only added to his dismay: the

colonel was just sitting and staring as his men streamed rearward. On

their heels came the brigades of Wood, Polk, and Johnson, right-wheeling

as they neared the Wilkinson Pike.

Wood, it seems, was the first to encounter Sheridan's contracted

salient. Attacking alone, he was shelled back into the timber "After

this," recalled a Yankee survivor, "there was but little firing for

some time; it was the calm—warning of the approaching

storm."

|

Sheridan instructed Greusel and Schaefer, whose troops were woefully

low on ammunition, to withdraw from the pike and into the cedars just as

Polk bore down on them from the west, Johnson in echelon to his left,

Wood in line to his right. Wood, it seems, was the first to encounter

Sheridan's contracted salient. Attacking alone, he was shelled back into

the timber. "After this," recalled a Yankee survivor, "there was but

little firing for some time; it was the calm—warning of the

approaching storm."

It was now 9:00 A.M. The determined resistance of Sheridan had

splintered the attacking gray lines. Vaughan, Maney, and Manigault

languished in the fields south of the Wilkinson Pike waiting for someone

to bring order to the confusion, while Cleburne's brigadiers found

themselves suddenly isolated, far in front of the remainder of the

Confederate left. Thus exposed, Wood had been mauled. Polk, advancing in

his stead, was similarly halted by Schaefer. Johnson, trying to succor

Polk, lost his way in the smoke-choked forest and drifted past him.

While Polk and Schaefer sparred, Manigault belatedly led his brigade

against Roberts's stronghold, now bolstered by Hescock and Bush's

batteries. The ensuing struggle was brief, and for a third time his

brigade stumbled rearward through the cedars.

If Manigault were to take the guns, he would need help. And so,

shortly after 9:00, he rode to Brigadier General Patton Anderson, whose

brigade remained unengaged to his right. Like Maney, Anderson agreed to

help Manigault. Two attempts to dislodge Bush and Hescock from the flank

having failed, Anderson decided to apply direct pressure.

|

GENERAL ROSECRANS (FAR RIGHT) VIEWS CONFEDERATE ARTILLERY FIRED AT

FEDERAL TROOPS AS DAYLIGHT FADES ON DECEMBER 31. (SMITHSONIAN

INSTITUTION)

|

He failed, and his regiments—committed one at a time were

slaughtered. The experience of the 30th Mississippi was typical. The

bluecoats held their fire while the 30th struggled through rows of

brittle corn-stalks. At 30 yards the command "Fire" rang out, and the

Rebel line melted into the earth. Private J. E. Robuck had been

irritated by the deep furrows that separated the rows when the charge

began—jumping them winded him. Now, trying to escape the hail of

bullets, he found them far too shallow—"I would have liked it

better had they been four feet deep." Mercifully, the command to retreat

was given. By Robuck's estimate the affair lasted just fifteen minutes,

during which time 201 men fell dead or wounded on one acre of

ground.

As the last of the attackers retreated out of range, Roberts's front

again fell silent. His brigade and Hescock and Bush's gunners were the

fulcrum of the Federal defense. With Greusel and Schaefer they had

fought seven brigades—almost half of all Southern units on the west

side of Stones River—to a standstill in ninety minutes of furious

combat. Some later would call it the most determined stand of the entire

war. Aging veterans would write with pride of the part they had played

in the "struggle in the cedars." But for the moment, as they reached

into their boxes to remove their final cartridges, many of Roberts's men

must have wondered if the next fight would be their last.

|

|