|

MY POOR ORPHANS

The second day of January dawned gray, cloudy, and cold, as

peculiarly dreary as the day before had been. And Federals remained,

their lines compact and well entrenched. Bragg at last accepted that

only a determined assault could dislodge Rosecrans. Learning that Sam

Beatty had occupied high ground on the east bank, he concluded to launch

his assault there. Possession of the hill held by Beatty was critical,

he wrote: "It commanded the entire field of battle. From this point,

either the enemy's or our line could he enfiladed." The Yankees, then,

must be driven from the east bank. And regardless of what Bragg thought

of Breckinridge, his was the only division available for the task.

At noon, Bragg summoned Breckinridge. Beneath a sweeping sycamore at

the river's edge, the two generals conferred. Major W. D. Pickett of

Hardee's staff, who was present, said that "General Bragg had already

determined to make the attack, as he at once commenced explaining the

order of attack." Breckinridge listened, and as he listened his anger

grew. After Bragg finished, the Kentuckian picked up a stick and

sketched his objections in the dirt. Drawing the boomerang-shaped rise

north of McFadden's Ford and west of the ground held by Fyffe's Federal

brigade, as well as the lower elevation he was to carry, Breckinridge

pointed out that the disparity in altitude meant that, in falling back,

the Federals would occupy a position that dominated his division's

objective. Bragg was unmoved. He fixed the hour of the assault at 4:00

P.M., one hour before dark. As it was already 2:30, Bragg suggested that

Breckinridge return to his command at once.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

UNION ARTILLERY SAVES THE DAY

At 4 P.M. on January 2, 1863, Breckinridge, as ordered by Bragg,

launched an attack on the Union left. After pushing the bluecoats from

the high ground, the Confederates were devastated by 58 cannon assembled

by Union chief of artillery Captain John Mendenhall. The grayclads lost

1,800 men killed, wounded, or captured in an hour. The battle was over;

Rosecrans claimed victory and the Confederates retreated south to the

Duck River.

|

Breckinridge rode off in disgust. He paused to confide in William

Preston his doubts: "General Preston, this attack is made against my

judgment, and by the special order of General Bragg. If it should result

in disaster, and I be among the slain, I want you to . . . tell the

people that I believed this attack to be very unwise, and tried to

prevent it."

In fairness to Bragg, Major Pickett recalled nothing "invidious or

critical" in his instructions to Breckinridge. Pickett agreed with Bragg

that Breckinridge's division was the least cut up and thus best able to

make an attack and that an assault launched near sunset, if successful,

would preclude a Federal counterattack.

Breckinridge's staff officers crisscrossed the lines carrying

orders—everywhere were the unmistakable signs of "a general waking

up." Before long, Brigadier General Roger Hanson's Kentucky

Brigade—known as the "Orphans"—was filing off Wayne's Hill to

join the rest of the division.

|

HENRY LOVIE SKETCH OR GENERAL NEGLEY'S

DIVISION CHARGE ACROSS THE RIVER. (COURTESY OF MIRIAM AND IRA D. WALLACH

PRINT COLLECTION, NY PUBLIC LIBRARY)

|

Sam Beatty and his brigade commanders watched this flurry of

activity closely. The Ohioan suspected trouble long before any

Confederate action suggested it, and during the morning he requested

that Grose's brigade be sent over to reinforce his left. Palmer

complied, and Grose deployed his command behind Fyffe. Beatty also

brought the 3rd Wisconsin Artillery across the river, and they

unlimbered in front of Price's brigade.

Reports came in from his front line during the morning that confirmed

Beatty's suspicions. Price notified him that he had counted fifteen

regiments and an undetermined number of cannon passing across his

front; a few minutes later, Confederate skirmishers opened fire on Price

and Fyffe. At 1:00 P.M., Confederate artillery joined in with a barrage

that continued intermittently for two hours.

Crittenden kept Rosecrans apprised of these ominous developments, and

Rosecrans moved at once to shore up the left. He pulled Negley's

division from the far right and placed it in reserve behind McFadden's

Ford. Morton's Pioneers formed on Negley's left a short time later.

Artillery followed. By 3:00 P.M., there were four brigades—those of

Miller, Stanley, Morton, and Cruft—and eighteen cannon within

supporting distance of Beatty.

Breckinridge's infantry, meanwhile, was still struggling into line.

What began as an annoying drizzle by noon had turned into a numbing,

driving sleet that slapped and blinded the soldiers as they tried to

dress ranks and even alignment. It was 3:00 before Colonel Randall

Gibson, successor to the wounded Dan Adams, had his brigade up and ready

behind the Kentucky Brigade of Roger Hanson. William Preston was not

even notified of the impending attack until 2:30; as his command was

then on the west bank, it is unlikely that he was in position much

before the signal gun sounded. When Preston did fall in behind Brigadier

General Gideon Pillow's brigade, he was troubled by the spacing between

the two waves. Three hundred yards customarily separated regiment- or

brigade-sized lines, or waves, in an attack. This spacing ensured that

the trailing line would be safe from enemy bullets that might sail over

the first line, yet near enough to provide effective support. But

Preston had been instructed to follow Pillow at a distance of just 150

yards.

|

A. E. MATHEWS RENDERING OF NEGLEY'S CHARGE. (LC)

|

The minutes passed slowly. "The short time seemed long as with

strained nerves," remembered a survivor. Ed Porter Thompson of the

Kentucky Brigade contemplated the ground over which he would be

charging: "[It] was an uncleared space, covered, for the most part, with

sassafras and other brushwood, and with briars, and a little ahead was

another open flat of ground, descending from the bushes, for some

distance, then ascending to the line upon which the enemy lay. The

general character of the ground along the whole division was undulating

and broken by thickets, forest trees and patches of briars."

A little after 3:00, skirmishers threw down the fences to their

front. A few minutes before 4:00, the men of the Kentucky Brigade

descried the fleshy form of General Hanson galloping toward them. Hanson

rode from regiment to regiment, and in a stentorian voice that everyone

could hear yelled out, "The order is to load, fix bayonets and march

through the brushwood. Then charge at the double quick to within a

hundred yards of the enemy, deliver fire, and go at him with the

bayonet." At precisely 4:00 P.M., a single cannon boomed, and "the line

seemed to leap forward."

Despite the telltale activity of his skirmishers an hour earlier,

Breckinridge's attack, launched with so little daylight remaining,

surprised most Federals. Given the hour, "we now supposed that the

attack which we had all day expected would be postponed until daylight

the next day," confessed a Union colonel.

Hanson's Kentuckians were the first to close with the enemy. Aside

from a turgid pond that forced a temporary change in alignment, the

brigade encountered no serious obstacles during the first 900 yards of

its advance; not even the hail of shot and shell had disrupted its

"perfect line of battle." Only 100 yards separated the Kentuckians from

Price's first line, which remained oddly silent. But the Federals simply

were waiting for targets too close to miss. At 90 yards they opened

fire, and the Rebel line shivered. But the Kentuckians kept coming, and

Price's front line collapsed. Retreating troops from the front-line

regiments threw those of the second line into confusion, and within

minutes the entire brigade was in retreat toward Stones River.

The Kentuckians carried the hill coveted by Bragg, but at the cost of

their commander's life. Only minutes earlier, Breckinridge had watched

his Kentuckians disappear over a rise and into a meadow. Breckinridge

followed the brigade across the briar-laced field. He and his staff were

near the abandoned first line of Federal breastworks when they spotted

Hanson, lying against a fence. A shell fragment had gashed his leg and

sliced open the femoral artery. Breckinridge tried vainly to stop the

bleeding, and his staff summoned an ambulance. Major Pickett never

forgot the scene: "It was a sight indelibly impressed on my

memory—the dying hero, his distinguished friend and commander

kneeling by his side holding back the lifeblood. . . . All this under

the fiercest fire of artillery than can be conceived."

|

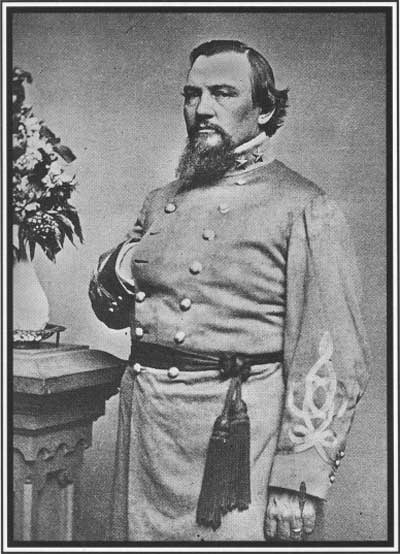

BRIGADIER GENERAL ROGER W. HANSON (LC)

|

Gideon Pillow's brigade, meanwhile, was fighting well. After a few

minutes of vicious, close combat, Pillow's Tennesseans routed Fyffe's

brigade. Despite this initial success, however, the Confederate attack

was beginning to unravel. A temporary pause by Pillow's left regiments

went unnoticed by the trailing units of Preston's brigade, until all

were badly intermingled. Further to the left, Colonel Gibson was having

similar problems. Gibson had left the front momentarily to redirect the

13th and 20th Louisiana, which were on a collision course with the

river. In his absence, the rest of the brigade became entangled with the

regiments of Hanson's brigade ahead of it.

The confusion became general. As Stones River meanders toward

McFadden's Ford it curls westward, then loops abruptly to the north. At

that point a nearby belt of timber and parallel high ground channelized

units approaching from the southeast; consequently, the brigades of

Hanson, now led by Colonel R. P. Trabue, and Pillow intermingled badly

as they neared the river. "The peculiar nature of the ground and the

direction of the river and the eagerness of the troops caused the lines

of General Pillow's brigade and this brigade to lap on the crest of the

hill," explained Trabue. An enlisted member of the Kentucky Brigade was

more direct—"In the madness of pursuit all order and discipline

were forgotten."

In the gathering gloom, Breckinridge's men fixed their gaze on

flashes of cannon fire from across the river and pushed on. There was

little on the east bank to stop them. In spite of Beatty's best efforts

at rallying them, his troops swarmed past toward the river.

|

It was 4:45 P.M. The sun had set and the sleet continued to slap at

the soldiers. In the gathering gloom, Breckinridge's men fixed their

gaze on flashes of cannon fire from across the river and pushed on.

There was little on the east bank to stop them. In spite of Beatty's

best efforts at rallying them, his troops swarmed past toward the

river.

Just as he had been two days earlier, Rosecrans was in the thick of

the fight now, scraping together idle units with which to bolster his

flagging left. The general was in only slightly firmer control of his

emotion than he had been on December 31. "Old Rosy came galloping down

the pike where we lay, the sweat pouring down his face, and sent for

Colonel Carlin," Colonel Hans Heg of the 15th Wisconsin wrote his wife

afterward. Heg quotes Rosecrans's impassioned command to Carlin: "I beg

you for the sake of the country and for my own sake to go at them with

all your might. Go at them with a whoop and a yell!"

While Rosecrans begged Carlin to save the country and his career,

Captain John Mendenhall, Crittenden's artillery chief, was methodically

concentrating all available guns to check Breckinridge. His efforts were

decisive. By the time the Rebels had crested the hill near McFadden's

Ford that was their objective, Mendenhall had assembled 45 cannon,

enough to blow the butternuts back to their line of departure. Although

Mendenhall gathered the guns at Crittenden's request, his success most

certainly exceeded the general's expectations. He deployed the guns

perfectly, arraying them hub to hub on a slope at least ten feet higher

than the highest point on the east bank of the river, so that their

crews would have unobstructed fields of fire.

|

ADVANCE OF COLONEL WALKER'S BRIGADE ON JANUARY 2 AS SKETCHED BY A. E.

MATHEWS. (LC)

|

Breckinridge's Confederates crested the hill above the ford, and

Mendenhall's guns roared their greeting. The destruction was terrific.

Wrote a Kentuckian: "The very earth trembled as with an exploding mine,

and a mass of iron hail was hurled upon them. The artillery bellowed

forth such thunder that the men were stunned and could not distinguish

sounds. There were falling timbers, crashing arms, and whirring of

missiles in every direction, the bursting of the dreadful shell, the

groans of the wounded, the shouts of the officers, mingled in one

horrid din that beggars description."

The Confederate collapse was abrupt and complete. Suddenness

surprised the Federals. The Rebels "cannot be said to have been checked

in their advance—from a rapid advance they broke at once into a

rapid retreat," averred Crittenden. Federal brigades poised on the west

bank splashed across the river in pursuit. They chased the Confederates

back to the very woods from which they had formed for the attack only

forty minutes before, halting only because nightfall made it too

dangerous to go on.

The disaster devastated Breckinridge. He raged "like a wounded lion,"

and the sight of his beloved Kentuckians reduced him to tears. Nearly

one-third of those engaged had fallen. Riding among the survivors,

Breckinridge cried again and again, "My poor Orphans! My poor

Orphans."

|

|