|

THE LINES FORM

Monday, December 29, broke bright and chill. At 10:00 A.M., after a

brief artillery barrage, the bluecoats splashed into the icy waters of

Stewart's Creek, prepared to meet Confederates on the opposite bank. To

their relief, they found only a few cavalry pickets; Maney had

withdrawn his infantry to Murfreesboro during the night. Crittenden

pushed forward in line of battle. Wheeler's troopers could not hope to

resist the onslaught, and the Union infantry waded Overall Creek and

pressed on along either side of the Nashville Turnpike.

At 3:00 P.M., with the sun already low and the chill of the winter's

eve setting in, the lead elements of the left wing caught sight of

Breckinridge's butternuts drawn up on the east bank of Stones River.

Although Palmer misconstrued the hasty retreat of Wheeler's cavalry for

a general withdrawal of the Confederate army from Murfreesboro, and

reported as much, neither he nor Wood, the senior officers present,

cared to be responsible for bringing about a battle, and so they halted

their divisions two miles shy of Murfreesboro to await the arrival of

Crittenden. Wood formed with his extreme left resting on the river and

his right astride the turnpike; Palmer extended the line southward into

a dense cedar brake, through which Negley struggled in the twilight; by

nightfall, he would join with Palmer's right, their lines connecting

obliquely and facing to the southeast into the impenetrable gloom of the

forest.

|

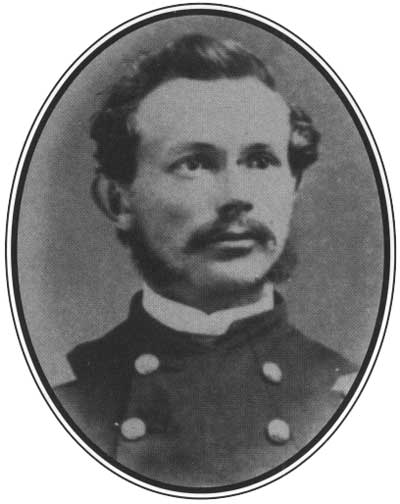

BRIGADIER GENERAL CHARLES G. HARKER (USAMHI)

|

Crittenden reached the front at dusk, just as orders came from army

headquarters directing the immediate occupation of Murfreesboro with one

division. Palmer now realized the error of his earlier report, which had

prompted this ludicrous order. He and Wood remonstrated with Crittenden

against a twilight advance, which the Kentuckian agreed to suspend only

while he sought out Rosecrans. At that moment Rosecrans arrived and

retracted the order.

But scattered fire from across Stones River indicated that contact

already had been made. The men of Wood's left brigade, commanded by the

impetuous Charles Harker, had crossed at a ford northwest of Wayne's

Hill after dark. Now, at 7:00 P.M., they ran into Rebel skirmishers near

the base of the hill. Only Cobb's Kentucky battery occupied the

elevation, and the Fifty-first Indiana Infantry darted forward through

brittle cornstalks to seize it. They came within a few yards of the guns

before two Rebel regiments under Colonel Robert Hunt arrived to throw

them back.

As they recrossed Stones River at 10:00 P.M., Harker's weary soldiers

were unaware how close they had come to taking Wayne's Hill and—had

they been supported by the rest of their division—rendering the

Rebel line on the east side untenable, perhaps altering the shape of the

battle to come.

At army headquarters near the Nashville Turnpike, Bragg and his

lieutenants prepared for the Union attack they believed would come at

dawn.

|

In a larger sense, however, it was Rosecrans, not Bragg, who occupied

the more precarious position. Nightfall on December 29 found only a

third of the Army of the Cumberland on the field, opposed by the entire

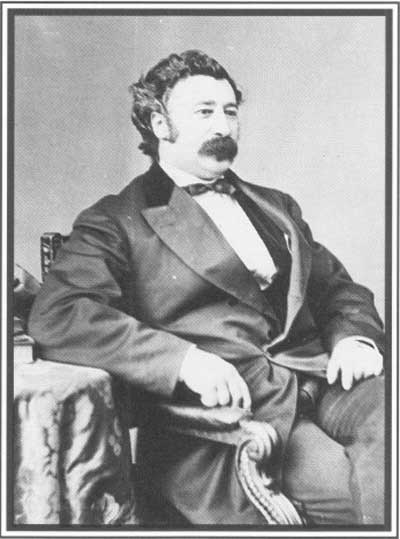

Confederate army. Southwest of Negley's position, between the Wilkinson

Turnpike and the Franklin road, Confederate cavalry ranged with

impunity. McCook's wing, which was to have joined Negley on his right,

was then bivouacked astride the Wilkinson Turnpike, on the west bank of

Overall Creek. A mile and a half of dense cedar thickets and a creek lay

between the right wing and the center.

At army headquarters near the Nashville Turnpike, Bragg and his

lieutenants prepared for the Union attack they believed would come at dawn.

By midnight, the Confederate line of battle was essentially complete.

Bragg had deployed his infantry so as to cover all approaches to

Murfreesboro; he considered this precaution necessary until "the real

point of attack should be developed."

|

STONES RIVER HEADQUARTERS OF GENERAL ROSECRANS. (BL)

|

Meanwhile, two and a half miles up the turnpike at the dilapidated

cabin that served as his headquarters, it had become apparent to

Rosecrans that McCook had no intention of moving further that night.

Exasperated, he rebuked the Ohioan with a peremptory order to move at

daybreak to bring his left to rest on Negley's exposed right, extending

his line southward, with his own right to rest on or near the Franklin

road, facing east.

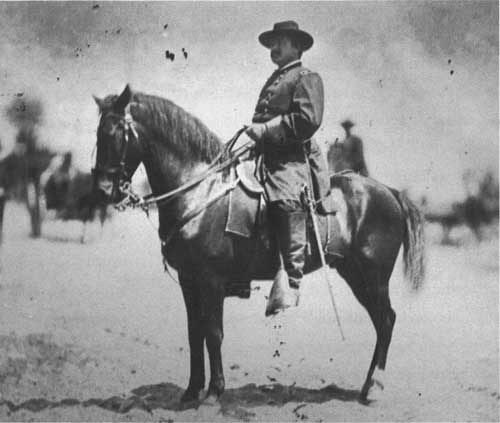

But McCook dallied. It was 9:30 A.M. On the thirtieth before he moved

and 2:00 P.M. before he neared the Harding house, about a half mile from

Polk's front line. There he fed Davis's infantry into line on the right

of Sheridan, who had led the advance. Leaving Johnson's division in

reserve (less the brigade of Edward Kirk, which had been sent forward to

extend Davis's right), McCook threw out a strong skirmish line and

resumed the movement. Immediately the Federals came under fire from

McCown's skirmishers, posted in a belt of timber to the southeast. After

two hours of slow, "cat and mouse" skirmishing with an enemy hidden

behind cedars and limestone outcrops, McCook called a halt.

As the twilight melted into darkness an uneasy silence fell across

the lines. Only 700 yards separated McCook's wing, now in position, from

the front line of Jones Withers. Negley's division had clawed its way

forward a bit farther and was now fronting east, a similar distance from

Cheatham. Rousseau had arrived at 4:00 P.M. Having no place to insert

him, Thomas ordered Rousseau to bivouac near Rosecrans's

headquarters.

For Bragg, the penultimate day of 1862 had been one of high anxiety.

He spent it in the saddle, listening as the firing on his left grew

louder, heralding the approach of McCook. Terminating on the Franklin

road, his left flank was in danger of being enveloped, should McCook

press his advantage. Consequently, he dispatched McCown's

division—his only real reserve—to this threatened part of the

field with orders to extend the Confederate line below the Franklin

road.

|

MAJOR GENERAL JAMES S. NEGLEY (USAMHI)

|

As the afternoon wore on and the skirmishing to the south rose to a

crescendo, Bragg—believing a general attack to be

imminent—directed Hardee, then on the east bank of Stones River, to

proceed at once to the left with Cleburne's division and take charge of

McCown's command as well. Before leaving, Hardee reminded Breckinridge

that he now alone was responsible for the integrity of the army's right.

The Kentuckian understood; he immediately moved the rest of the Orphan

Brigade onto Wayne's Hill and reinforced Cobb's battery with more

cannon, finally securing that key ground.

While Cleburne felt his way into position, Bragg conferred with

his corps commanders. One day waiting for an attack that never came had

been enough; Bragg resolved to seize the initiative.

|

While Cleburne felt his way into position, Bragg conferred with his

corps commanders. One tension-filled day waiting for an attack that

never came had been enough; Bragg resolved to seize the initiative.

Assuming that Rosecrans had stripped his left to support

McCook—from whom he still expected any Union attack to come—Bragg

suggested that Rosecrans be attacked along the Nashville

Turnpike. Polk disagreed. As the transfer of McCown and Cleburne to the

left had greatly extended that part of the line, Polk proposed a turning

movement directed against the Federal right flank. Bragg concurred.

Hardee would begin the attack with his two divisions of infantry and

Wharton's cavalry, which was to gain the Federal rear rapidly and create

as much confusion as possible. Polk would take up the attack in turn,

executing a "constant wheel to the right" with his right flank serving

as pivot.

The object was simple: Push the enemy back to Stones River and, by

interposing Wharton's troopers on the Nashville Turnpike, cut him off

from his supply base at Nashville. All present except perhaps

Bragg—knew that the execution would be infinitely more difficult.

A wheeling movement of the sort Bragg had in mind was challenging enough

in open terrain; over broken ground laced with cedar brakes and cut by

fences and farms it might well prove impossible. Compounding the

difficulty was Bragg's desire that the attack be made in successive

lines that were to advance simultaneously while maintaining a uniform

spacing. Lastly, his generals would be working under unfamiliar command

relationships. As the same broken ground that jeopardized a wheeling

movement also rendered the supervision of a four front-line brigade by a

single commander impossible. Withers and Cheatham agreed to split their

commands: Cheatham would direct the movements of Loomis, Manigault,

Vaughan, and Maney, while Withers led Donelson, Stewart, Anderson, and

Chalmers. Each general would have a more compact force to command.

Logical in theory, it remained to be seen whether this novel arrangement

would work in battle.

|

MAJOR GENERAL ALEXANDER MCCOOK (USAMHI)

|

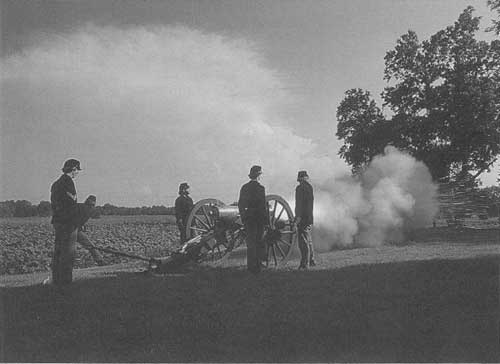

|

A LIVING HISTORY DEMONSTRATION OF UNION ARTILLERY AT STONES RIVER

NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD. (NPS)

|

Meanwhile, Rosecrans was putting the final touches on his own plan.

Like Bragg, he was determined to attack in the morning. And, ironically,

he also decided to assail the enemy's right. Crittenden would initiate

the action, crossing Horatio Van Cleve's division at McFadden's Ford and

sending it against Breckinridge. Wood was to join Van Cleve on his right

and with him drive toward Murfreesboro. This done, Wood's artillery

would unlimber on Wayne's Hill and enfilade the Confederates across the

river; meanwhile, Palmer and Thomas would press forward from the west,

sweeping the enemy across the river and through town. McCook was to

occupy the best defensive ground he could find, refuse his right, and

accept Bragg's attack; if none came, he was to engage the enemy to his

front with a force sufficient to prevent his reinforcing other parts of

the field.

Rosecrans was confident but troubled by McCook's dispositions. He

underscored to McCook the need for him to hold his ground for at least

three hours.

"You know the ground; you have fought over it; you know its

difficulties. Can you hold your present position for three hours?" asked

Rosecrans.

"Yes, I think I can," McCook answered.

"I don't like the facing so much to the east, but must confide that

to you, who know the ground," added Rosecrans. "If you don't think your

present the best position, change it. It is only necessary for you to

make things sure."

With that, McCook returned to the right wing.

The weather turned foul as the night deepened. A northerly wind

whipped up, chilling the moist air and whistling dismally through the

trees. Up and down the line, units prepared for battle. The thoroughness

of a unit's preparations depended on the ability and concern of its

commanding officer. On the right, where the need for vigilance was

greatest, an air of indifference took hold. Perhaps it was their

ignorance of the strength of the Confederate infantry laying just 300

yards away that caused the generals of the right wing to forgo reasonable

precautions, or perhaps it was their certainty that Crittenden's

attack would eliminate any threat to their end of the line. Whatever the

reason, there were indications of the whirlwind to come. That

afternoon, Stanley had sent McCook a garrulous civilian, found near his

home on the Franklin road, who provided exact information on Bragg's

dispositions in that sector. McCook, a bit more concerned for his

extreme right, directed Johnson to deploy Willich's brigade beside

Kirk's.

Ominous sounds drifted through the cedars and across the fields,

warning those who cared to listen. On the picket line, Sergeant Lewis

Day of the 101st Ohio heard troops and artillery pass by all night long.

Day and his comrades relayed the information rearward. "To this day, it

seems strange that no attention was given to this matter," Day later

wrote. Others recalled similar experiences.

The meaning of the sounds was clear to at least one commander in the

right wing. A restive brigadier General Joshua Sill sought out his

division commander, West Point classmate Phil Sheridan, at 2:00 A.M. to

relate his fears. Together they walked into the tangled forest where

Sill's front line rested. There they heard the unmistakable sounds of

moving infantry and artillery. Off to McCook's headquarters near the

Gresham house they rode. The right wing commander was asleep on a bale

of straw. Sheridan awoke him and explained the threat as he and Sill saw

it. McCook dismissed their concerns—Crittenden's morning attack would

put a swift end to any Confederate designs on their own sector. Sheridan

and Sill left, their fears by no means allayed.

It was 4:00 A.M. The monotonous firing between the picket lines had

subsided and "all recent signs of activity in the enemy's camp were

hushed. A death-like stillness prevailed in the cedars to our front,"

recalled a veteran. In less than three hours it would be shattered with

a fury that none who survived would forget.

|

|