|

THE CAMPAIGN TO APPOMATTOX

The coming of night on the final day of March 1865 found

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant a worried man. For ten grueling

months he had personally directed Union operations in and around the

strategically important transportation and manufacturing town of

Petersburg, Virginia. An attempt to seize the city in June 1864 had

instead become a tedious siege that stretched through to spring. One

visible result was the miles of trenches, forts, and redoubts that

spread like a cancer across the Virginia countryside; another was the

seemingly endless series of small but sharp engagements, none of which

was decisive, but which cumulatively tightened the Federal vise.

Approximately 42,000 Federals fell killed, wounded, or missing in

fighting for little more than points of temporary advantage such as

Peebles Farm, Hatcher's Run, or the Jerusalem Plank Road.

|

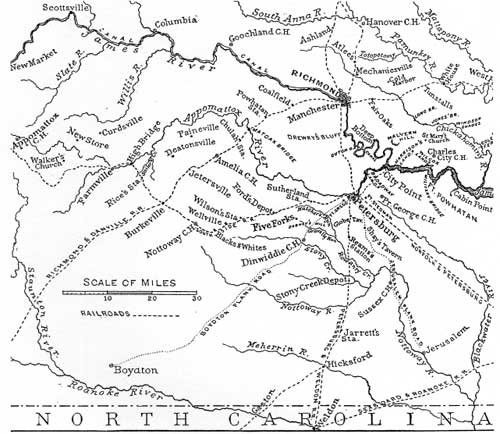

A PERIOD MAP OF THE APPOMATTOX AREA. (BL)

|

Throughout it all Grant had held his lines with a tenacious grip,

forcing his opponent to do the same. The coming of spring meant that the

muddy Southside roads would become firm enough to support a rapid

movement of troops. Now Grant worried that the enemy commander, General

Robert F. Lee, would somehow find a way to slip out of the ring

tightening around Petersburg and escape south to link up with the only

other Confederate army in the east, General Joseph E. Johnston's, near

Raleigh. If that happened, declared Grant's military secretary Adam

Badeau, "a long and tedious and expensive campaign, consuming most of

the summer might be inevitable."

Always a man of action, Grant again had ordered armed men into motion

as he increased Union pressure against Lee's extreme right flank, which

was anchored near Burgess' Mill, five miles southwest of Petersburg.

There was fighting there on March 29 as the Federal Fifth Corps pushed

across the Boydton Plank Road below the Burgess' mill pond, followed by

a day-long combat on March 31, when the Fifth Corps, supported by the

Second, probed, but failed to penetrate, the Confederate defensive

works. The March 31 fighting alone cost the Union more than 1,800

casualties, while Confederate losses were about 800.

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL ULYSSES S. GRANT PHOTOGRAPHED BY MATHEW BRADY. (LC)

|

|

GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE (LC)

|

Further south and west this same day, a force of approximately 9,000

bluecoated riders under Major General Philip H. Sheridan battled rain,

mud, and angry Rebels in a bold attempt to end run the Confederate

entrenchments to cut Petersburg's only rail link to still-functioning

supply depots. Sheridan's thrust toward the South Side Railroad was

blocked near Dinwiddie Court House by a mixed force of cavalry and

infantry under the overall command of Major General George E. Pickett.

As night fell, Sheridan held on to his position only through a

combination of stubbornness, luck, and a lack of aggressive

follow-through by his opposite number. Grant ordered infantry to

Sheridan's assistance, and the pugnacious cavalry officer vowed to

resume the action in the morning.

A few soggy miles from where Grant chewed on his cigar and his

problems, Robert E. Lee pondered again the impossible alternatives facing him.

Since assuming command of the Army of Northern Virginia in 1862, Lee had

almost never faced a battle without the odds against him, but never did

they loom as long as they did this last day of March 1865. The siege of

Petersburg had been a death sentence for his once vaunted army, which

had suffered about 28,000 casualties. A brutal fall season of steady

combat, followed by a winter marked by periods of near starvation and

mass desertions, left the forces defending Petersburg and Richmond

dangerously weakened, with morale at an ebb point. Any tactical move Lee

made along one point of his stretched lines meant that he was risking

disaster at another. When his scouts detected the Union buildup against

his right flank, he felt he had to act, not only to protect the South

Side supply line but to keep the enemy from flanking his entire

Petersburg position. So Lee patched together a mobile force to meet

whatever it was that Grant was moving against him.

Lee's cavalry, which had been scattered from Richmond to areas south

of the entrenched Petersburg perimeter, was ordered to concentrate near

the threatened flank under the command of his nephew Major General

Fitzhugh Lee. From the Bermuda Hundred area between Richmond and

Petersburg, Lee drew out two brigades of Pickett's division, added a

third on duty near Petersburg, pushed in two

more from the forces at Burgess' Mill, and sent them out to fight

alongside the cavalry. More than 10,000 of Lee's precious military

assets were being used to thwart the enemy's design.

|

MAJOR GENERAL FITZHUGH LEE (USAMHI)

|

|

LIEUTENANT COLONEL HORACE PORTER (BL)

|

Events on March 31 augured well for Lee's gamble. His troops posted

along the White Oak Road near Burgess' Mill not only repulsed the Yankee

probes, but for a few heady moments even ran roughshod over two

divisions of the enemy Fifth Corps. Pickett's mobile force stopped

Sheridan's riders near Dinwiddie Court House and were pressing him

heavily as night fell. But a victory celebration proved premature.

The fighting along the White Oak Road was ended by strong Union

reinforcements forcing Lee's men back into their entrenchments, with

little to show for their efforts. And early on the moming of April 1,

Lee learned to his horror that the victorious Pickett was withdrawing

his mixed force from the Dinwiddie area. Informed too late to halt this

retrograde movement, Lee nevertheless insisted that Pickett make a stand

at the strategically important road crossing known as Five Forks.

Pickett's move had been caused by the slow approach of the infantry

reinforcements Grant had ordered to Sheridan—Major General

Gouverneur K. Warren's entire Fifth Corps. The path of Warren's advance

put some of his troops squarely on Pickett's left flank and rear so the

Confederate officer felt he had no option but to retreat from such an

exposed position. Both commanders—Grant and Lee—now waited to

learn what the events of April 1 would bring.

Twenty-four hours later, just after darkness had settled in,

Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter, one of Grant's most trusted aides,

pushed his way along the sloppy trails from Five Forks to army

headquarters. "The roads in places were corduroyed with captured

muskets," Porter recalled. "Ammunition trains and ambulances were still

struggling forward for miles; teamsters, prisoners, stragglers, and

wounded were choking the roadway." Porter's orderly could not hold back

the news the two carried, and he shouted to a group of soldiers along

the way that a great Union victory had been won this day at Five Forks.

Instead of a cheer, one of the soldiers in the group derisively thumbed

his nose and yelled, "No, you don't—April Fool!"

Minutes later, Porter was at Grant's headquarters, shouting the glad

tidings: in a battle that had begun late in the afternoon, troops under

Sheridan and Warren had attacked Pickett's men at Five Forks and, in

little more than two hours of combat,

had soundly routed the defenders. Of the approximately 10,000 men

under Pickett at Five Forks, nearly a third were killed, wounded, or

captured. "It meant the beginning of the end," Porter enthused, "the

reaching of the 'last ditch.'" Grant listened to his excited aide, then

calmly stood up and walked into his tent. When he emerged a few minutes

later he clutched a fistful of dispatches for transmission to the

various commands around Petersburg. Said Grant with no emotion: "I have

ordered an immediate assault along the lines."

|

SKETCH BY ALFRED WAUD OF THE FEDERAL CHARGE AGAINST PICKETT'S FLANK AT

FIVE FORKS. (LC)

|

It took time for Grant's orders to work their way through the

various levels of command, and it was not until dawn, April 2, that the

troops facing the Petersburg lines were ready to go. The action against

the enemy's fortified positions was concentrated along the axis of

the Jerusalem Plank Road and against the lines snaking southwest of

the city that shielded the Boydton Plank Road. The assault against the

first was made by the Union Ninth Corps, which fought a bloody but

inconclusive battle lasting throughout the day. Against the other target, however,

the Federal attack by the Sixth Corps succeeded in punching a gaping

hole in the thinly stretched C.S. defenses. Prompt follow-up attacks by

the Federals then rolled up Lee's lines as far south as Burgess' Mill.

It took a suicidal last stand by a handful of defenders in a pair of

detached forts near the city—Whitworth and Gregg—to prevent

the Yankee formations from entering Petersburg itself.

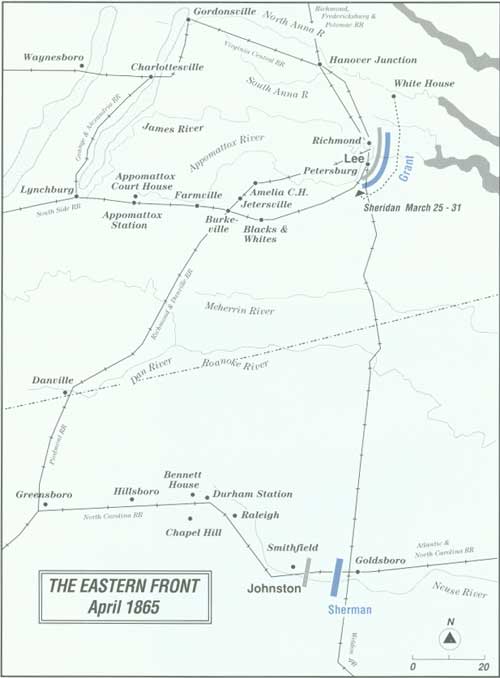

THE EASTERN FRONT, APRIL 1865: THE BEGINNING OF THE END IN THE EAST

While Sherman's 90,000 men watched Johnston's 37,000 men in North

Carolina, the Union armies under U.S. Grant moved to break the stalemate

at Petersburg. Using Sheridan's cavalry just arrived from the Shenandoah

Valley, Grant struck at Lee's extreme right flank. Sheridan's victory at

Five Forks cut Lee's last supply line, the South Side Railroad, and

forced him to abandon Petersburg and Richmond. Lee's only hope now was

to move south to link-up with Johnston.

|

|

Robert E. Lee was a constant presence along this front as his men

fought desperately to buy enough time to save his army. Only the

last-minute arrival of reinforcements summoned from Richmond allowed

Lee to stabilize his lines when darkness ended the fighting. It was

during this day that Lee learned the fate of Pickett's force and that

the enemy had cut the South Side Railroad, eliminating the only military

reason to hold Petersburg. Once it was evacuated, Richmond too must

fall. It was a little after 10:00 A.M., April 2, when Lee dictated the

message to Jefferson Davis that signaled a decisive downturn in

Confederate fortunes: "I advise that all preparations be made for

leaving Richmond tonight."

|

THE UNION ATTACK ON FORT GREGG, APRIL 2, 1865, AS SKETCHED BY

CIVIL WAR ARTIST ALFRED WAUD. (LC)

|

|

WAUD'S SKETCH OF THE STORMING OF FORT MAHONE. (LC)

|

More than a month earlier, Lee had anticipated such a circumstance

and issued a series of contingency orders. The April 2 assaults had two

serious effects on Lee's calculations. First, they initiated combat that

resulted in the loss (mostly through capture) of many of the veteran

troops posted along the lines struck by the Sixth Corps. Second, they

forced events to happen much more rapidly than had been anticipated in

Lee's planning, which, in turn, strained the Confederate command system

to the breaking point. Messages went astray, and critical orders failed

to reach their destinations. Perhaps the most serious breakdown occurred

when Lee's urgent request for the C.S. Commissary Department in Richmond

to send all available food rations to Amelia Court House was

delayed.

|

|