|

It was the detritus from this battlefield that met the eyes of Robert

E. Lee as he rode east from Rice's Station seeking to find out what was

delaying the rear of his army. As the extent of the disaster became

clear to him, Lee was heard to say, "My God! has the army dissolved?" (A

short time afterward, while discussing his intended movements with an

officer sent up from the provisional seat of government in Danville, Lee

muttered, "A few more Sailor's Creeks and it will be over-ended.)

Lee rode back to Rice's Station arriving there about sundown, and

gave orders for the retreat to continue to Farmville, where there would

be rations waiting. The troops with Longstreet would move directly from

Rice's to that point, while Gordon's battered but intact corps,

reinforced by the division under Major General William Mahone, would

cross the Appomattox using a spectacular railroad trestle known as High

Bridge. This latter option was available to Lee only because a bold

attempt by a 900-man Federal raiding party to destroy it (launched out

of Ord's command as it approached Rice's Station) had been stopped short

of its mission by a cavalry force hastily dispatched by Longstreet. The

Federals had all been killed or captured, but the Confederates had paid

a high price in the number of senior officers dead or mortally wounded,

including Brigadier General James Dearing.

|

THE CAPTURE OF HIGH BRIDGE

We moved after the enemy at 5:30 A.M. and did not

come up with him until we got to High Bridge. We were riding with

General Barlow's division near its head, when our skirmishers opened

the ball, and we, following them closely, soon came out upon the bluff

which overlooked the valley of the Appomattox. The valley was half a

mile wide. The river, which was unfordable and not over a hundred feet

wide, ran close to our bank. The railroad bridge, called High Bridge,

rested on twenty or more piers, each 125 feet high, and thus spanned

the valley from bluff to bluff. The valley was clear of trees and we saw

everything that transpired in it. At our end of the bridge, where we first

came in sight of the valley, was a strong earthen fort with a number

of guns which the rebels had injured as much as possible in a brief

time; a hundred yards in front the wooden bridge which crossed the

river was afire, and the enemy's skirmishers essayed to prevent ours

from extinguishing the fire. At the farther side of the valley, the

rebel column was climbing up on the bluff and disappearing from sight,

and the great railroad bridge was burning furiously at their end. A

portion of General Barlow's column hurried down to the small bridge and,

forcing a passage, extinguished the flames and saved the bridge, and

then our skirmishers deployed on the other side of the river and slowly

drove the enemy's skirmishers across the plain, every man in both

lines being in plain sight of us, so that we saw each shot and each man

drop and every movement, a grander display than it is possible to

produce in any amphitheater of these days.

From Days and Events

by Thomas L. Livermore, Colonel of the 18th New Hampshire Volunteers

|

THE CONFEDERATES BURNED SEVERAL SPANS OF THE RAILROAD BRIDGE OVER

THE APPOMATTOX RIVER KNOWN AS HIGH BRIDGE, BUT THE WAGON BRIDGE

BELOW IT REMAINED INTACT. (LC)

|

|

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL E. P. ALEXANDER (LC)

|

Lee kept his men moving throughout the night of April 6 and well into

the next morning. Gordon's and Mahone's soldiers safely passed across

the Appomattox River at High Bridge (actually the site of two

bridges—an elevated railroad trestle paralleled on the valley floor

below by a wagon bridge). A small rear guard was left behind to watch

over the detachment of engineers assigned to destroy the spans.

Exhaustion was taking its toll. As they moved toward Farmville, Lee's

weary legions were steadily shedding men.

|

Exhaustion was taking its toll. As they moved toward Farmville, Lee's

weary legions were steadily shedding men. E. P. Alexander remarked: "The

road was one sea of mud through which men, horses, ambulances,

artillery, & cavalry splashed & floundered & stopped in the

darkness & splashed & floundered & stopped again." Operating

under Lee's instructions, Longstreet's men entered Farmville, crossed to

the north side of the Appomattox River, and went into camp, where they

enjoyed their first regular issue of rations since leaving Richmond. The

cumulative pressure and debilitating series of disasters had stressed

Lee to such an extent that his only thought was to find some breathing

space for his army. He believed that if he could get all his remaining

troops safely over to the north side of the Appomattox and burn the

bridges behind him, he would have successfully isolated himself from

pursuit—for a while at least. This belief became an obsession that

clouded his judgment.

The river barrier was more imagined than real, and the position it

would place his forces in was, in many ways, more dangerous than if he

had remained south of it. James Longstreet was quick to point out that

even with both the Farmville bridges burned, the river alone would not

stop the enemy. Said Longstreet afterward "I reminded him that there

were fords over which his [i.e., the Federal] cavalry could cross, and

that they knew of or would surely find them." When E. P. Alexander, one

of Lee's most trusted junior officers, had a chance to look at a map and

see the route Lee intended for his columns, the young artilleryman was

appalled. "The most direct & shortest road to Lynchburg from

Farmville did not cross the river as we had done, but kept up the south

side near the railroad." Alexander saw at once that the route Lee

planned to use took the troops away from the railroad (and their

supplies) and would not allow them to angle back toward the south until

they reached the headwaters of the river, near a place called Appomattox

Court House. By remaining south of the river, Lee would have a far

shorter march to reach that same point. When he dared suggest this to

Lee, the weary response was: "Well there is time enough to think about

that."

|

PICTURED LEFT TO RIGHT: MAJOR GENERAL PHILIP H. SHERIDAN,

BRIGADIER GENERAL JAMES W. FORSYTH, MAJOR GENERAL

WESLEY MERRITT, BRIGADIER GENERAL THOMAS DEVIN, AND

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE A. CUSTER. (NA)

|

As if to mock Lee's decision, word arrived that the troops

retreating over High Bridge had failed to destroy the spans

sufficiently to do more than briefly delay the Yankee pursuit. Worse, enemy

infantry had already crossed in some force. The time Lee had hoped to

purchase by moving north of the river had evaporated even before he had

it in his hand. He showed a rare flash of anger toward those who had

allowed this to happen. As the chief of artillery for the Second Corps,

A. L. Long, later wrote, "He spoke of the blunder with a warmth and

impatience which served to show how great a repression he ordinarily

exercised over his feelings." Among the last actions completed before

abandoning Farmville, Lee's commissary general ordered the undistributed

rations in railroad cars sent off to the west, expecting that the

Confederate army would be able to catch up with them further along the

line.

The Federal pursuit this day was concentrated in three columns. One,

consisting of the Second Corps troops that had battled Gordon on April

6, reached High Bridge about 7:00 A.M. Portions of both the railroad and

wagon bridges were in flames when the bluecoated troops rushed forward,

drove off the Rebel rear guard, and managed to save the lower

structure. A few sections of the towering railroad span collapsed, but

the damage was limited and was soon made good by U.S. military

engineers. By 9:15 A.M. Andrew Humphreys had his men across the river

and moving west.

Approaching Farmville from Rice's Station were infantry from the

Army of the James (under Ord), preceded by George Crook's cavalry

division. This force fought its way through several roadblocks and by

11:00 A.M. was poised on the hills just south of Farmville. There was a

brief cavalry melee in the streets before the last Confederate defenders

pulled back to the north side of the river and the two bridges were set

afire.

The third principal Yankee force in motion consisted of the other two

divisions of Sheridan's cavalry, which marched on a westerly heading to

Prince Edward Court House, where the riders prepared to block any

attempt by Lee to move toward Danville.

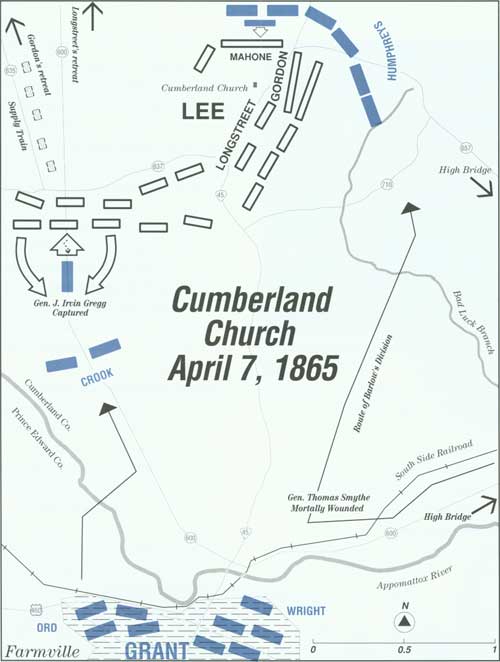

Falling back before the Federals that had crossed at High Bridge, the troops

under Gordon and Mahone began around 2:00 P.M. to take a defensive position along

a ridge of high ground near Cumberland Church. At the same time, Longstreet's

men, aided by Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry, took station off to the west,

both to cover Gordon's right flank and to screen the remaining supply

wagons as they slowly hauled off to the northwest. A Union cavalry

brigade that had managed to ford the Appomattox (as Longstreet had

warned) made a dash at the train but was neatly ambushed. In the resulting

fight, which began around 4:00 P.M., the Federal officer in charge,

Brigadier General J. Irvin Gregg, was captured.

|

MAJOR GENERAL A. A. HUMPHREYS (BL)

|

Even as this was happening, Andrew Humphreys's Second Corps

approached along the north side of the Appomattox. Two of his divisions

angled in a northwesterly direction hoping to cut off the Confederate

retreat, while a third moved directly along the railroad. Just north of

Farmville, this lone division struck Lee's rear guard, and in the

ensuing skirmish one of the Federal brigade commanders, Brigadier

General Thomas Smythe, was mortally wounded. He would linger until April

9, becoming the last Union general to be killed as a direct result of a

combat action.

The rest of Humphreys's command ran into Rebel resistance about 1:00

P.M. and spent the next few hours maneuvering into a position facing the

Cumberland Church line. Then, starting around 4:00 P.M., the Federals

launched a series of attacks that tested but never seriously threatened

the Confederates here. The fighting ended at dark, with Union losses

numbering about 571 killed, wounded, or missing. Confederate casualties

were uncounted, though a Farmville resident later recalled that the

"moans of the dying could be heard for hours after the battle. A number

of Confederate soldiers were buried just north of Cumberland

Church."

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

LEE TURNS AWAY

As long as Lee remained south of the Appomattox he maintained a slight

lead over Grant, though he was subject to constant attack by the enemy

cavalry. At Farmville, Lee crossed to the north side hoping for respite

from the relentless Union pursuit. His relief was short-lived, for

Federal troops under Humphreys, using a wagon bridge, were also on the

north side. Humphreys struck Lee at Cumberland Church in a sharp but

inconclusive fight. Union cavalrymen made a dash at Lee's supply train

but were ambushed and repulsed. After rejecting Grant's first

communication requesting his surrender, Lee marched off to the west.

Grant sent one wing of his force after Lee, while the other moved to cut

him off.

|

U. S. Grant entered Farmville just about the time all this fighting

was getting under way. He set up headquarters in the Randolph House,

where he was soon receiving messages from his commanders in the field.

While he was there, both the Army of the James troops under Ord and the

Sixth Corps under Wright took position in town along the south side of

the river. Shortly before 5:00 P.M., Grant remarked to Major General

John Gibbon, "I have a great mind to summon Lee to surrender." Not long

afterward, Grant's adjutant general Seth Williams was given the

dangerous task of carrying Grant's message to the Confederate picket

line. Trigger fingers were itchy this night, and before he could

establish the purpose of his mission, Williams came under a fire that

killed the orderly riding with him. He at last managed to hand the

message over, and it was delivered to Robert E. Lee around 10:00 P.M.

The note was typical of Grant, straight and to the point:

"The results of the last week must convince you of the

hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern

Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my

duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of

blood by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate

army known as the Army of Northern Virginia."

Lee showed the note to one of his staff officers, Lieutenant Colonel

Charles Venable, who suggested he just ignore it.

"Ah," Lee said, "but it must be answered."

Other officers offered their opinions. Longstreet's response was

succinct. "Not yet," he said. Lee wrote the following reply.

"I have rec'd your note of this date. Though not entertaining the

opinion you express of the hopelessness of further resistance on the

part of the Army of N. Va.—I reciprocate your desire to avoid

useless effusion of blood, & therefore before considering your

proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its

surrender."

The message was brought out to the picket line and turned over to

Seth Williams for delivery to U. S. Grant. Taking no chances, Williams

rode back the way he had come (via High Bridge), not arriving in

Farmville until early in the morning of April 8.

|

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN GIBBON (LC)

|

Even as the Federal staff officer was in transit, Lee began pulling his

men out of their positions around Cumberland Church. With the wagons

safely ahead of him, Lee was able to fill several roads with his

columns. Gordon's corps, accompanied by the cavalry, would travel only a

short distance south before turning north and west onto the Lynchburg

Stage Road. Longstreet's corps had further north to go

before swinging west onto a plank road that ran parallel to the stage

road. Lee's next problem would occur a few miles along that westward

leg, at a place called New Store. Here the two roads merged into one,

making a natural bottleneck that would slow everything to a crawl.

Many of his men were moving in a dull fog, barely conscious of their

surroundings. A cavalryman assigned to straggler patrol was aghast at

the sight of the soldiers "who had thrown away their arms and knapsacks

[and were] lying prone on the ground along the roadside, too much

exhausted to march further, and only waiting for the enemy to come and

pick them up as prisoners."

Once at New Store, Lee adjusted the order of march. Gordon, who had

overseen the army's rear guard since Amelia Court House, would now take

the lead, followed by Longstreet, with Fitzhugh Lee's troopers covering

the rear. He also accomplished a bit of military housekeeping by

relieving Richard H. Anderson, Bushrod Johnson, and George E. Pickett of

their commands. It was likely that Lee was approached by his

artillery chief, Brigadier General William N.

Pendleton, who had a difficult matter to discuss. Several of Lee's

subordinates had talked together during the night and decided that the

time had come to see what terms the enemy was willing to offer. They

believed that by suggesting such a course for Lee, they would go on

record as having proposed the idea and thus save him from any blame. Lee

listened quietly while the dignified Pendleton explained all this.

|

DRAWING BY W.L. SHEPPARD OF CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS AT A WELL

DURING THEIR RETREAT. (BL)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL BUSHROD JOHNSON (BL)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE E. PICKETT (BL)

|

"I trust it has not come to that!" Lee said after Pendleton had

finished. "We certainly have too many brave men to think of laying down

our arms. They still fight with great spirit, whereas the enemy does

not. And, besides, if I were to intimate to General Grant that I would

listen to terms, he would at once regard it as such an evidence of

weakness that he would demand unconditional surrender—and sooner

than that I am resolved to die. Indeed, we must all determine to die at

our posts."

Pendleton's reply was that "every man would no doubt cheerfully meet

death with him in discharge of duty, and that we were perfectly willing

that he should decide the question." Nevertheless, it was the first

tremor of capitulation ever to shake the Army of Northern Virginia.

Everything was on the move at Farmville on April 8 as the Federals

took up the chase. The Sixth Corps had crossed to the north side of the

Appomattox during the night while, further north, the Second Corps

returned to the Cumberland Church battlefield, buried its dead, and set

out after Gordon's command. The man leading the corps was as anxious as

any in his ranks to close the gap and finish the thing. One amused staff

officer recalling seeing Andrew Humphreys this day "wearing much the

expression of an irascible pointer, he having been out ahead of his

column, and getting down on his knees and peering at foottracks, through

his spectacles, to determine by which the main body had retreated." Once

the Second Corps passed off to the west, the Sixth Corps followed the

route taken by Longstreet's men.

U. S. Grant received Lee's reply that morning in Farmville. Though it

dodged the question he had asked, Grant thought it was "deserving

another letter." Before departing Farmville, he composed this

response:

"Your note of last evening in reply of mine of same date, asking

the condition on which I will accept the surrender of the Army of

Northern Virginia is just received. In reply I would say that, peace

being my great desire, there is but one condition I would insist upon,

namely: that the men and officers surrendered shall be disqualified for

taking up arms again against the Government of the United States until

properly exchanged. I will meet you, or will designate officers to meet

any officers you may name for the same purpose, at any point agreeable

to you, for the purpose of arranging definitely the terms upon which the

surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia will be received."

|

WARTIME ILLUSTRATION OF CONFEDERATE PRISONERS. (BL)

|

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL WILLIAM PENDLETON (BL)

|

After seeing the note on its way, Grant and his staff mounted,

crossed to the north side of the river, and followed after Humphreys's

and Wright's troops. The sun was out, and the weather was pleasant, but

Grant was not in condition to enjoy it. By afternoon he was suffering

from such a blinding headache that he could no longer ride. Headquarters

were soon established at "Clifton." There Grant tried some home remedies hoping to

cure his pounding temples, but to no avail. He climbed into the only

bed in the house, trusting that a little sleep would do what foot soaks

and a wrist poultice could not.

The burden of action against the Confederacy this day was carried by

the cavalry under Sheridan. Starting out from several encampments

located around Prospect Station (eight miles west of Farmville), the

Yankee riders were formed into a northern and southern striking force,

the former under Brevet Major General Wesley Merritt, the latter under

George Crook. Following the South Side Railroad line, Crook's troopers

galloped into Pamplin Station around noon, where they captured the

supply trains sent out from Farmville on April 7. Meanwhile, Sheridan,

on a course toward Appomattox Station, learned that one of his

resourceful scouts had successfully conned loyal Southern railroad

engineers into bringing their supply trains up from Lynchburg to

Appomattox Station, where they waited for Lee's hungry foot soldiers. If

the Union cavalry could reach there first, a great blow would have been

struck against Lee's designs.

Even as these eager columns of blue-coated riders pushed toward

that place, other long files of infantry trudged in their wake. Marching

hard in Sheridan's dust were white and black soldiers of the Army of the

James under Ord and the Fifth Corps under Griffin from the Army of the

Potomac. Victory lingered just beneath the horizon, and General Ord was

determined that his men would be in at the kill. He

prowled along the toiling rows of sweating men, driving them forward

with fierce encouragement. "I promise you, boys, that this will be the

last day's march you will have to endure," he yelled to one group of

weary foot sloggers. "One good steady march, and the campaign is

ended," he shouted to another bunch.

|

MAJOR GENERAL WESLEY MERRITT (NA)

|

|

PHOTOGRAPH OF GRANT TAKEN AROUND THE TIME OF THE APPOMATTOX

CAMPAIGN. (LC)

|

As the day's shadows began to lengthen, the leading elements of

General Merritt's wing drew near to Appomattox Station. The first squad

on the scene captured one of the several trains waiting at the depot,

while behind these riders, the rest of the regiment began to spread out

to gather in others. Colonel Alanson M. Randol, the officer directing

this deployment, felt a hand on his shoulder and turned to see General

Custer next to him. "Go in, old fellow, don't let anything stop you,"

Custer said with rising excitement, "now is the chance for your stars.

Whoop em up; I'll be after you."

More dusty blue riders scattered among the stopped trains and before

long jubilant Yankees were running the captured engines back and forth,

"with bells ringing and whistles screaming."

|

More dusty blue riders scattered among the stopped trains and before

long jubilant Yankees were running the captured engines back and forth,

"with bells ringing and whistles screaming." Their celebration was cut

short by a salvo of cannon shells that burst among them. It turned out

that most of Lee's surplus artillery pieces, marching well ahead of the

slower infantry columns, had gone into bivouac just outside the station

area and were now belching fury at the Yankee interlopers. Supporting

the cannoneers were a scratch force of military engineers and a small

cavalry brigade.

After several piecemeal attempts to rush this position were blasted

back, Custer finally organized an all-out charge. Sometime between 8:00

and 9:00 P.M., the Yankee cavalrymen advanced to the attack. The

fighting was bitter but brief. It ended with the Union troopers in

possession of the field but most of the Rebel artillery pieces safely

away, many withdrawn through the village of Appomattox Court House to

meet the leading files of Gordon's corps. A few Federal cavalrymen

pressed the retreating cannoneers right into the town, only to be gunned

down by Gordon's pickets. One gut-shot Yankee sergeant writhed in

terrible agony, begging to be killed, until death came to release

him.

|

MAJOR GENERAL EDWARD O. C. ORD POSES WITH THE TABLE

LEE USED DURING THE SURRENDER AT THE MCLEAN HOUSE. (LC)

|

|

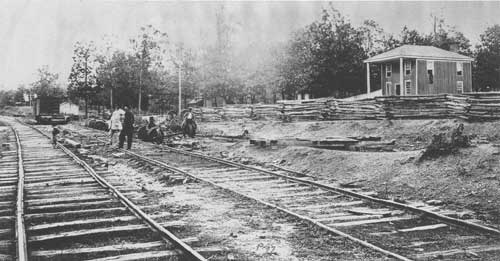

A PHOTOGRAPH NEAR APPOMATTOX STATION TAKEN A FEW MONTHS

AFTER THE SURRENDER (LC)

|

|

|