|

Philip Sheridan arrived at Appomattox Station during the final phase

of this day's combat. In a dispatch to Grant written at 9:20 P.M.,

Sheridan confidently predicted that if the infantry could reach him by

morning, "we will perhaps finish the job....I do not think Lee means to

surrender until compelled to do so."

A few miles from where Sheridan scribbled this message, the veteran

soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia were going into camp after an

exhausting march from Cumberland Church. Major General William Mahone,

part of Longstreet's command, wound up spending this night in a log

shanty "occupied by a family of deformed people—that made me shiver

to behold."

Robert E. Lee's headquarters this night were located near Rocky Run,

north of the Appomattox River. Shortly before reaching this camp, he

received Grant's note written that morning in Farmville. Without

consulting any of his staff or other officers, he sat down and drafted a

reply.

"I rec'd at a late hour your note of today. In mine of yesterday I

did not intend to propose the surrender of the Army of N. Va.—but

to ask the terms of your proposition. To be frank, I do not think the

emergency has arisen to call for the surrender of this Army, but as the

restoration of peace should be the sole object of all, I desired to know

whether your proposals would lead to that and I cannot therefore meet

you with a view to surrender the Army of N. Va.—but as far as your

proposal may affect the C.S. forces under my command & tend to the

restoration of peace, I shall be pleased to meet you at 10 A.M. tomorrow

on the old stage road to Richmond between the picket lines of the two

armies."

|

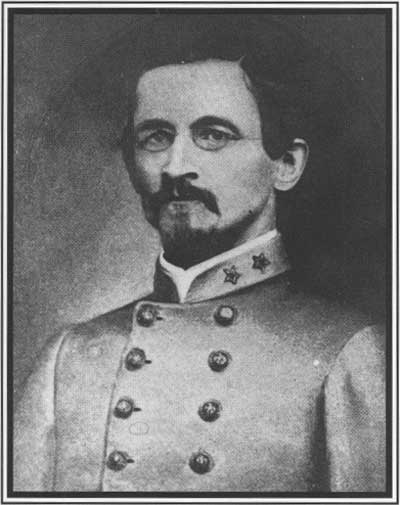

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE ARMSTRONG CUSTER (LC)

|

Once his headquarters had been set up, Lee summoned his corps

commanders—Longstreet, Gordon, and Fitzhugh Lee—for a council

of war. Nobody was certain whether it was just some Yankee cavalry in

front, or if the cavalry screened a larger infantry force. Robert E. Lee

believed that the horsemen were without support and would give way under

pressure. Gordon, perhaps remembering how quickly the Yankee infantry

came on him April 6 and 7, wasn't so sure. But orders were orders. When

dawn arrived, Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry would clear a path, backed up by

Gordon's infantry. Once the road had been opened, the rest of the army

would pass through to continue the retreat. Robert E. Lee was careful to

add a proviso, that if Fitzhugh Lee's advances found enemy infantry

present, they all would have no choice but to "accede to the only

alternative left us."

Lee's reply to Grant's second Farmville note reached the ailing

lieutenant general around midnight. When the courier bearing the message

reached "Clifton," the small crowd of staff and hangers-on who filled

the first floor edged near the stairway to eavesdrop. They were not

disappointed.

Grant handed the note over to his blunt, outspoken chief of staff,

Brigadier General John Rawlins, who read it aloud—loud enough for

most of those below to understand every word. Once before, in the winter

of the Petersburg siege, Confederate military authorities had tried to

initiate discussions regarding a general political settlement. At that

time Grant had been told by Lincoln in no uncertain terms that his

authority extended only into the military sphere. As Rawlins saw it, it

was precisely into this forbidden policy area that Lee was attempting to

lure Grant.

"You asked him to surrender," Rawlins reminded his chief. "He replied

by asking what terms you would give if he surrendered. You answered by

stating the terms. Now he wants to arrange for peace—something

beyond and above the surrender of his army—something to embrace the

whole Confederacy, if possible. No Sir! No Sir."

Grant took a soldier's view. He was certain that it was Lee's pride

speaking, and if only the two of them could sit down face-to-face they

could "settle the whole business in an hour." Rawlins was unconvinced,

and there the matter remained until morning when, after losing in his

attempt to sleep his headache away, Grant arose and composed this

reply.

|

LEE CONFERS WITH GORDON, LONGSTREET, AND FITZHUGH LEE

DURING THEIR LAST COUNCIL OF THE WAR. (NPS)

|

"Your note of yesterday is received. As I have no authority to

treat on the subject of peace the meeting proposed for 10 A.M. today

could lead to no good. I will state, however, General, that I am equally

anxious for peace with yourself and the whole North entertain the same

feeling. The terms upon which peace can be had are well understood. By

the South laying down their arms they will hasten the most desirable

event, save thousands of human lives, and hundreds of millions of

property not yet destroyed."

Following breakfast, Grant made a spur-of-the-moment decision to ride

to Sheridan's front—a journey that would place him out of touch for

several hours and take him away from the point where Lee expected him to

be. Various explanations were subsequently offered by others to explain

this decision—from a cynical desire to exclude General Meade from

taking part in any surrender negotiations, to an astute ploy designed to

preempt Lee's hope to discuss a broader peace agenda. It is also

possible that Grant simply wanted to be with his most trusted

subordinate at this critical moment. Ironically, even as Grant and his

party rode southward, events were moving to closure at Appomattox Court

House.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN AARON RAWLINS (NPS)

|

Throughout the early morning hours of April 9, John Gordon and

Fitzhugh Lee positioned their men just west of the village, preparatory

to clearing the Yankee cavalry out of the way. Gordon's infantry took

station on either side of the Lynchburg Stage Road, with Fitzhugh Lee's

troopers gathered on the right flank of the infantry line. The smooth

start of this operation was marred by a sharp disagreement between the

two corps commanders over whether the infantry or the cavalry should go

first. The impasse ended when one of Gordon's officers, Major General

Bryan Grimes, offered to organize the advance.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE LAST CHANCE

Believing that only a thin screen of Federal cavalry blocked him, Lee

ordered Gordon and Fitzhugh Lee to open up the road. They attacked at

dawn and quickly overran the enemy road blocks, but before they could

exploit this, hard-marching Union infantry arrived to close the circle.

Lee ordered a truce and waited near an apple tree for his messages to

reach Grant, who was approaching from the south. Contact was made a

little before noon, and arrangements made to meet at the home of Wilmer

McLean in Appomattox Court House. As this was happening Fitzhugh Lee and

a portion of his cavalry moved off to Lynchburg.

|

As the morning sun began to burn off the fog blanketing the quiet

meadows west of the village, the long Confederate formations were seen

and targeted by a pair of Yankee cannon posted in a roadblock not a

quarter mile distant. This defiant challenge spurred the battle lines

into action and the men began to move forward, accompanied by the eerie

Rebel yell. With Fitzhugh Lee's men sweeping in on their flank and

(literally) a third of the Rebel army in their front, the Federals

manning the roadblock took to their horses.

A second, more stoutly defended position, located about a half mile

west of the first, held out longer against Fitzhugh Lee's attacks, as

the hard-pressed Yankee troopers fought to buy time for their infantry

supports to arrive. The action here witnessed several wild cavalry

charges, coupled with hand-to-hand melees that scattered across the

countryside in a free-form dance. Behind the battling Southern

cavalrymen, Gordon's long infantry lines swung down like a door hinged

on the village to clear the Stage Road area of any remaining pockets of

Yankee troopers. The plan up to this point had come off as advertised;

the escape route for Lee's army stood invitingly open.

|

A WARTIME SKETCH OF THE VILLAGE OF APPOMATTOX COURT HOUSE WITH

THE MCLEAN HOUSE ON THE RIGHT. (BL)

|

More men were quick-timing it to the point of combat. These were foot

soldiers from Ord's Army of the James, whose hard-driving commander had

indeed gotten them to the scene of action in time. The first units to

enter the action had little trouble dispersing Fitzhugh Lee's men but

were rocked back by Gordon's veterans. However, more men were coming up,

including black soldiers. While Ord's battle line took shape across the

Stage Road, troops from Griffin's Fifth Corps came up on Ord's right

flank. An increasingly solid wall of infantry now barred Lee's escape.

"It did not take a Solomon to tell that our army was in bad shape, both

as to its organization and the position it occupied," declared a C.S.

artilleryman.

Well before it was obvious to everyone that the army was trapped, Lee

had resolved to carry through on the meeting he had requested of Grant.

In the few hours around sunrise, he conversed with several officers,

seemingly to test his conclusions and, perhaps, stiffen his resolve. A

staff officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles S. Venable, sent to confer

with Gordon before the clearing attack began, returned with the

Georgian's pessimistic assessment that he could accomplish "nothing

unless ... heavily supported by Longstreet's corps." Comments such as

this may have darkened Lee's normally unflappable mood, for when

Brigadier General Pendleton asked why he had dressed so formally this

day, Lee answered, "I have probably to be General Grant's prisoner and

thought I must make my best appearance." When E. P. Alexander, the

artillery officer, loudly doubted the wisdom of surrendering the army

rather than having it disperse, Lee was firm in his desire to save the

region from the ravages of armed men not under military discipline. "We

would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to

recover from," he declared.

At about 8:30 A.M., around the same time that Gordon's and Fitzhugh

Lee's men were clearing the Stage Road southwest of the village, Lee

rode out to the northeast to talk with Grant. He met instead a Federal

staff officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles A. Whittier, who handed over

Grant's note rejecting the proposed conference and again offering a

simple military convention. Lee pondered this for a few moments, then

turned to his staff officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Marshall, and

said, "Well, write a letter to General Grant and ask him to meet me to

deal with the question of the surrender of my army." Marshall drafted

the response which Lee signed.

"I received your note of this morning on the picket-line, whither

I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced

in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this

army. I now request an interview in accordance with the offer contained

in your letter of yesterday for that purpose."

Lee was anxious to have all hostilities suspended. He told the Union

aide to allow the ranking officer on this front to read the note in the

hope that the truce then existing might be extended. That request wound

up with General Meade, who, with Grant out of communication, felt he had

no option but to continue operations as ordered. Lee's party had to

retreat as Federal skirmishers began to move out from Humphreys's lines.

Even though he felt duty bound to order his men forward, Meade was also

anxious to avoid farther bloodletting. At his suggestion, Lee drafted a

second note to be sent to Grant through Sheridan's front. It contained

much the same information as the first, but Meade thought it might catch

up with the lieutenant general sooner than the one passing through his

lines.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

LEE SEEKS AN AUDIENCE

This map depicts the northern portion of Lee's final position. While

Gordon's men attempted to break through the Federal cordon further

south at Appomattox Court House, Longstreet's men faced the

Federal wing that had followed Lee after Farmville. It was in the

no-man's land between these two forces that Lee rode on the morning of

April 9, seeking to speak with Grant. But Grant was not available,

having left this wing earlier in the morning in order to join the other,

so Lee turned back.

|

Lee also sent word back to Gordon authorizing him to put out flags

of truce to halt the fighting on his front. That done, he rode slowly

toward the village, finally stopping near a soon-to-be-famous apple

tree just north of the river, where he awaited Grant's reply. A short

distance from where Lee sat, foot soldiers from Longstreet's corps took

up a line of battle facing the village, ready to support Gordon if

needed. With Longstreet's men was a long row of

fieldpieces representing every gun E. P. Alexander could muster.

|

RUFUS ZOOBAUM'S DRAWING FIGHTING AGAINST FATE SHOWS

CONFEDERATES' LAST GASP ATTEMPTS TO WARD OFF THE ADVANCING

UNION TROOPS. (NPS)

|

|

A VIEW OF APPOMATTOX COURT HOUSE TAKEN IN 1892. THIS PERSPECTIVE

IS HOW GRANT WOULD HAVE SEEN THE VILLAGE FOR THE FIRST TIME. (NPS)

|

Gordon's retrograde movement was not without some fighting as the

paths of a few blue and gray units brought them into contact. But then

the words "cease fire" began to run among the men. Here and there white

flags of truce began to appear. Once he was certain that his troopers

were no longer needed, Fitzhugh Lee led two of his divisions (reduced to

about 2,400 men) off the field under a previously announced plan to

break out of the Yankee cordon.

An odd calm began to settle across Appomattox Court House. Men who

only moments before were prepared to kill or be killed now rested on

their weapons in plain sight of each other. In some places small

clusters of officers or enlisted men met to wonder together about what

was happening. On one part of the field a Virginia cavalrymen named W.

L. Moffett came across a comrade, Sam Walker, mortally wounded in the

morning's action. "Moffett, it is hard to die now just as the war is

over," Walker said.

Lee's first note written to Grant this day finally caught up to the

lieutenant general's party just before noon a short distance west of

Walker's Church. It was given to John Rawlins, who read it and passed it

to Grant without comment. Grant scanned it briefly before returning it

to Rawlins with the comment, "You had better read it aloud, General." As

the meaning of Lee's words became clear, there was a halfhearted attempt

at three cheers, but everyone was too choked up to manage it. "Will that

do, Rawlins?" Grant asked at last. "I think that will do," the chief of

staff replied.

Grant quickly dictated a reply.

"Your note of this date is but of this moment (11:50 A.M.)

received. In consequence of my having passed from the Richmond and

Lynchburg road to the Farmville and Lynchburg road I am at this writing

about four miles west of Walker's church, and will push forward to the

front for the purpose of meeting you. Notice sent on this road where you

wish the interview to take place will meet me."

While an officer rode ahead with this message, Grant and his group

followed at a more reasonable pace. The general's headache was gone. The

"moment I saw the note," he wrote, "I was cured."

As this was taking place, officers from both sides gathered in front

of the Appomattox Courthouse to talk. According to John Gibbon, who was

present, "all seemed hopeful that there would be no further necessity

for bloodshed." Only Sheridan brought any temper to the impromptu

conference. Perhaps piqued because his party had been fired upon when it

first attempted to cross the lines, Sheridan was not offering any

conciliation. "He is for unconditional surrender and thinks we should

have banged right on and settled all questions without asking them,"

another participant remembered. Finally, around 1:00 P.M., the group

broke up.

|

LIEUTENANT COLONEL CHARLES MARSHALL (LC)

|

|

CUSTER RECEIVES A FLAG OF TRUCE. SKETCH BY ALFRED WAUD. (LC)

|

Grant had entrusted his reply to Lieutenant Colonel Orville E.

Babcock. It took this officer about an hour to reach Lee, who was still

near the apple tree. After carefully noting the time of receipt on the envelope, Lee read the

message. Still worried about fighting breaking out again, he asked

Babcock if he would send a note to General Meade asking him to extend

the cease-fire on that front. Babcock at once

drafted the message, which reached Meade about an hour later.

|

CARRYING THE FLAG OF TRUCE

The following account was written by Confederate Captain R. M.

Sims to a member of the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers after the

war.

Charleston, S. C., May 22 1886.

Dear Sir: — Your letter of May 1st, enquiring as to detail of

carrying the flag of truce at Appomattox, has remained unanswered longer

than I intended from pressure of business, sickness in my family and

general reluctance to write on this subject and disinclination to write

at all on any matter or subject.

The flag was a new and clean white crash towel, one of a lot for

which I had paid $20 or $40 apiece in Richmond a few days before we left

there. I rode alone up a lane (I believe there was only a fence on my

right intact), passing by the pickets or sharpshooters of Gary's

(Confederate) Calvary Brigade stationed along the fence, enclosing the

lane on my right as I passed. A wood was in front of me occupied by

Federals, unmounted cavalry, I think. I did not exhibit the flag until

near your line, consequently was fired upon until I got to or very near

your people. I went at a full gallop. I met a party of soldiers, and

near them, two or three officers. One was Lieutenant-Colonel Whitaker,

now in Washington, and the other a major. I said to them: "Where is

your commanding officer, General Sheridan? I have a message for him."

They replied: "He is not here, but General Custer is, and you had better

see him." "Can you take me to him?" "Yes." They mounted and we rode up

the road that I came but a short distance, when we struck Custer's

division of cavalry, passing at full gallop along a road crossing our

road and going to my left. We galloped down this road to the head of the

column, where we met General Custer. He asked: "Who are you, and what do

you wish?" I replied: "I am of General Longstreet's staff, but am the

bearer of a message from General Gordon to General Sheridan, asking for

a suspension of hostilities until General Lee can be heard from, who has

gone down the road to meet General Grant to have a conference." General

Custer replied: "We will listen to no terms but that of unconditional

surrender. We are behind your army now and it is at our mercy." I

replied: "You will allow me to carry this message back?" He said: "Yes."

"Do you wish to send an officer with me?" Hesitating a little, he said:

"Yes" and directed the two officers who came with me, Lieutenant-Colonel

Whitaker and the major, whose name I don't know, to go with me. We rode

back to Gordon in almost a straight line. Somewhere on the route a Major

Brown, of General Gordon's (Con.) staff, joined me, I think after I had

left Custer.

On our way back to Gordon two incidents occurred. Colonel Whitaker

asked me if I would give him the towel to preserve that I had used as a

flag. I replied: "I will see you in hell first; it is sufficiently

humiliating to have had to carry it and exhibit it, and I shall not let

you preserve it as a monument of our defeat." I was naturally irritated

and provoked at our prospective defeat, and Colonel Whitaker at once

apologized, saying he appreciated my feelings and did not intend to

offend. Passing some artillery crossing a small stream, he asked me to

stop this artillery, saying: "If we are to have a suspension of

hostilities, everything should remain in status quo." I replied:

"In the first place, I have no authority to stop this artillery; and

secondly, if I had, I should not do so, because General Custer

distinctly stated that we were to have no suspension of hostilities

until an unconditional surrender was asked for. I presume this means

continuing the fight. I am sure General Longstreet will construe it

so...."

... Pardon the hurried manner in which this is written. Let me hear

from you again. What part were you in this surrender?

(Signed)

R. M. Sims, late Captain C. S. A.

|

|

WAR TIME SKETCH OF MCLEAN HOUSE EUSTACE COLLETT. (NPS)

|

|

|