|

Most of Lee's soldiers received their paroles by April 15. Then,

recalled a Tar Heel, "We were turned out into the world most of us

without any money, with one weatherbeaten suit of clothes, and nothing

to eat, entirely on the mercy of strangers." General Chamberlain never

forgot the sight that morning of these men "singly or in squads, making

their way into the distance, in whichever direction was nearest

home, and by nightfall we were left there at Appomattox Court House

lonesome and alone."

|

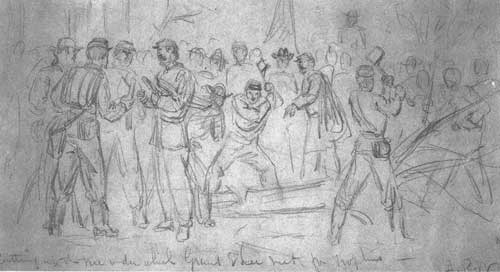

ALFRED WAUD SKETCH OF SOLDIERS CHOPPING UP THE APPLE TREE

UNDER WHICH GRANT AND LEE SUPPOSEDLY MET, FOR SOUVENIRS. (LC)

|

|

UNION SOLDIERS SHARING THEIR RATIONS WITH STARVING

CONFEDERATE TROOPS. (BL)

|

|

THE RETURN OF GENERAL LEE FROM THE MCLEAN HOUSE

This account is from Fighting for the Confederacy—The

personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander. (Courtesy

of The University of North Carolina Press)

It was about half past four o'clock when we saw the general on old

Traveller, & Col. Marshall, who had accompanied him, appear in the

road returning; still about a half mile off. A strong desire seized me

to have the men do something, to indicate to the general that our

affection for him was even deeper than in the days of greatest victory

& prosperity.

Ordinary cheering seemed inappropriate, so I quickly sent & had

Col. Jno. Haskell, & all the artillery officers near, bring their

men & form them along the roadside, with orders to uncover their

heads, but in silence, as the general passed.

But the infantry line, being at rest & noting us artillerists at

something, swarmed down to see. And thus, as the general came up, our

few hundred artillery were swallowed up in a mob of infantry, & some

one started to cheer, & then, of course, all joined in.

And Gen. Lee stopped & spoke a few words. It was I believe only

the second time that he ever spoke to a crowd. The first occasion was

when a crowd at a station had called him from the train, as he went from

Washington City to Richmond to enter the service of Virginia at the

breaking out of the war. He advised them to go to their homes &

prepare for a bloody & desperate struggle.

Now, he told the men in a few words that he had done his best for

them & advised them to go home & become as good citizens as they

had been soldiers. As he spoke a wave of emotion seemed to strike the

crowd & a great many men were weeping, & many pressed to shake

his hand & to try & express in some way the feelings which shook

in every heart. As he passed on toward his camp he stopped & spoke

to me for a moment & told me that Gen. Grant had very generously

agreed that our soldiers could keep their private horses, which would

enable them to plant crops before it was too late. This seemed to be a

very special gratification to him. Indeed Gen. Grant's conduct toward us

in the whole matter is worthy of the very highest praise & indicates

a great & broad & generous mind. For all time it will be a

good thing for the whole United States, that of all the Federal generals

it fell to Grant to receive the surrender of Lee.

The terms of the surrender were drawn up by Gen. Grant himself in a

brief note rapidly written, & all the details as afterward carried

out seem to me a remarkable model of practical simplicity.

|

|

THIS IS A ROMANTICIZED DEPICTION OF LEE AND GRANT'S

MEETING ON APRIL 10, THE DAY AFTER THE SURRENDER

MEETING. IT WAS PAINTED IN 1922 BY STANLEY ARTHURS.

COURTESY DELAWARE STATE MUSEUMS, DOVER)

|

|

AFTER THE SURRENDER

by General Horace Porter

Mr. McLean had been charging about in a manner which indicated that

the excitement was shaking his nervous system to its center; but his

real trials did not begin until the departure of the chief actors in the

surrender. Then relic-hunters charged down upon the manor-house, and

began to bargain for the numerous pieces of furniture. Sheridan paid the

proprietor twenty dollars in gold for the table on which General Grant

wrote the terms of surrender, for the purpose of presenting it to Mrs.

Custer, and handed it over to her dashing husband, who galloped off to

camp bearing it upon his shoulder. Ord paid forty dollars for the table

at which Lee sat, and afterward presented it to Mrs. Grant, who modestly

declined it, and insisted that Mrs. Ord should become its possessor.

General Sharpe paid ten dollars for the pair of brass candlesticks;

Colonel Sheridan, the general's brother, secured the stone ink-stand;

and General Capehart the chair in which Grant sat, which he gave not

long before his death to Captain Wilmon W. Blackmar of Boston. Captain

O'Farrell of Hartford became the possessor of the chair in which Lee

sat. A child's doll was found in the room, which the younger officers

tossed from one to the other, and called the "silent witness." This toy

was taken possession of by Colonel Moore of Sheridan's staff, and is now

owned by his son. Bargains were at once struck for nearly all the

articles in the room; and it is even said that some mementos were

carried off for which no coin of the republic was ever exchanged. Of the

three impressions of the terms of surrender made in General Grant's

manifold writer, the first and third are believed to have been

accidently destroyed. The headquarters flag which had been used

throughout the entire Virginia campaign General Grant presented to me.

With his assent, I gave a portion of it to Colonel Babcock.

From Campaigning With Grant, originally published by The

Century Company.

|

TABLE AT WHICH LEE SAT (left); TABLE AT

WHICH GRANT WROTE THE ARTICLES OF SURRENDER (center); CHAIR IN WHICH

GRANT SAT (right).

|

|

Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House did not end the Civil War.

Joseph E. Johnston's army in North Carolina held out until April 26, and

other C.S. military departments in the West continued to resist until

June 2, when the last of them, the Trans-Mississippi, formally

capitulated. The conflict was not legally ended until a presidential

proclamation of August 20, 1866, declared that "peace, order,

tranquility and civil authority now exist in and throughout the whole of

the United States."

|

LOCAL CITIZENS POSE IN FRONT OF THE CLOVER HILL TAVERN

SHORTLY AFTER THE WAR. (NPS)

|

|

AN 1865 LITHOGRAPH OF THE MEMORABLE EVENT. (LC)

|

The image of Appomattox Court House as a point of ending and

beginning grew with the passing years. It became the accepted practice

to date the war from the firing on Fort Sumter to the surrender at

Appomattox.

|

Yet the image of Appomattox Court House as a point of ending and

beginning grew with the passing years. It became the accepted practice

to date the war from the firing on Fort Sumter to the surrender at

Appomattox. Few significant military actions took place after

Appomattox. Author Fletcher Pratt, in his popular short history of the

conflict, ended his narrative on April 9. The same could be said for

other histories by Catton, Donald, and others. A committee appointed in

1892 to designate a national Civil War holiday wound up with a short

list of three events: Lincoln's birthday, the day the Emancipation

Proclamation was issued, and the date Lee surrendered at Appomattox.

|

A COPY OF "GENERAL ORDER NUMBER 9." (NPS)

|

|

THE FIFTH CORPS RECEIVES THE FORMAL SURRENDER

By General Meade's order the Fifth Corps, General Griffin in command,

was designated to receive the formal surrender. General Griffin, having

selected his former division, now commanded by General J. L.

Chamberlain, to receive the arms and colors of the Confederates.

At 9 A.M., April 12th, the One Hundred and Fifty-fifth was relieved

from its position on the skirmish line, which it had been occupying

continuously since the morning of the 9th, and with the Third Brigade

was drawn up on the right of the road leading into the village, muskets

loaded and bayonets fixed, General Chamberlain and staff on the right of

the line, adjacent to the hamlet. At 9:30, a half hour later, the

silvery tones of the bugles brought the troops to attention and soon the

first Confederate brigade made its appearance, marching through the

village and along the road in front of the Third Brigade. When the head

of the Confederate column reached the left of the Third Brigade, and

directly opposite the One Hundred and Fifty-fifth, their commander gave

the command, Halt! Close Up! Front Face! Stack Arms! Unsling Cartridge

Boxes! Hang on Stacks! This being done, the command was given, Right

Face! Forward! Countermarch by File Right, March! and away they went

unarmed and colorless, back to their camp.

As soon as this brigade, which it was learned was Evans' Brigade, of

Gordon's Corps, had departed, the troops of the Third Brigade, by orders

of General Chamberlain, then stacked arms and took down the Confederate

stacks, piling the muskets on the ground in their rear, muzzles outward.

One Confederate brigade succeeded another all day long, continuing until

nearly 5 P.M.; and as S. W. Hill, a member of the One Hundred and

Fifty-fifth, who was present at these final ceremonies, expresses it,

"There was no need to stop for lunch, as there was not a cracker nor a

bean in the Third Brigade, General Grant's orders of 30,000 rations to

the Confederates having exhausted the supplies of his own men."

It was evident that the Confederates were much dejected, though there

appeared an expression of relief on their faces as they marched away,

and their depression may have been caused more by hunger and emaciation

than by the chagrin of defeat. Most of them acted in a soldierly manner,

but occasionally one would display ill-temper by peevishly throwing his

cartridge box at the foot of the stacks instead of hanging it

thereon.

|

THE LAST SALUTE. (PAINTING BY DON TROIANI. PHOTO COURTESY OF

HISTORICAL ART PRINTS, SOUTHBURY, CT.)

|

The color guards, having stacked their arms, the color bearers

deposited their flag against their stacks some of them with tears in

their eyes bidding farewell with a kiss to the tattered rags they had

borne through so many dangers. The scene during the day was pathetic in

the extreme, and tears welled up in the eyes of many a seasoned veteran

in the Union lines.

When the last Confederate brigade had disappeared there was a pile

of muskets shoulder-high, which the army wagons soon hauled away. The

Army of Northern Virginia, the pride of the Confederacy, the invincible,

upon which their hopes and faith had been reposed, had disappeared

forever, existing thenceforth in memory only.

The total number of Confederates who received paroles at Appomattox

reached about 28,000, though less than half that number had arms to

surrender. Between the opening of the campaign on the 29th of March and

the 9th of April more than 19,000 prisoners and 689 pieces of artillery

had been captured.

Twenty-eight thousand hatless, shoeless, famishing men were cast

adrift by the collapse of the Confederacy, hundreds of miles from their

poverty-stricken homes. While the low-hovering smoke of battlefields had

lifted, yet the embers and ashes of war had left desolate the entire

intervening region, and the outlook of these disheartened and

penniless men was indeed cheerless. With the true American spirit of

humanity, those of the Union soldiers who had any money freely and

generously shared it with their former enemies, and many Confederates

were assisted to reach their homes in the Southwest by way of northern

railroads.

From Under the Maltese Cross, originally published by the

155th Pennsylvania Regimental Association.

|

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOSHUA L. CHAMBERLAIN (LC)

|

|

HONOR ANSWERS HONOR

The momentous meaning of this occasion impressed me deeply. I

resolved to mark it by some token of recognition, which could be no

other than a salute of arms.

Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men

whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster,

nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now,

thin, worn, and famished, but erect and with eyes looking level into

ours, walking memories that bound us together as no other bond—was

not such manhood to be welcomed back into a Union so tested and

assured?

Instruction had been given: and when the head of each division column

comes opposite our group, our bugle sounds the signal and instantly our

whole line from right to left, regiment by regiment in succession, gives

the soldiers salutation, from the order arms to the old carry—the

marching salute. Gordon at the head of the column, riding with heavy

spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up,

and taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his

horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the

point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command,

gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position

of the manuel—honor answering honor. On our part not a sound of

trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of

vain glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an

awed stillness rather, and breath-holding as if it were the passing of

the dead!

As each successive division masks our own, it halts, the men face

inward towards us across the road, twelve feet away; then carefully

dress their line, each captain taking pains for the good appearance of

his company, worn and half starved as they were. The field and staff

take their positions in the intervals of regiments; generals in rear of

their commands. They fix bayonets, stack arms; then, hesitatingly,

remove cartridge-boxes and lay them down. Lastly, reluctantly, with

agony of expression—they tenderly fold their flags, battleworn and

torn, blood stained, heart-holding colors, and lay them down; some

frenziedly rushing from the ranks, kneeling over them, clinging to them,

pressing them to their lips with burning tears. And only the Flag of the

Union greets the sky!

From Joshua L. Chamberlain's memoir The Passing of the Armies,

G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1915

|

|

THE SURRENDER OF THE ARMY OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA, APRIL 12, 1865.

PAINTING BY KEN RILEY. COURTESY WEST POINT MUSEUM, U.S. MILITARY

ACADEMY, WEST POINT, NY)

|

|

VIEW OF THE COURTHOUSE BUILDING AND MCLEAN HOUSE,

CIRCA 1890. (NPS)

|

Appomattox Court House did not stop the guns, nor did it solve any

of the profound social and emotional issues that had ignited the war.

Yet in the desperate valor of the campaign leading up to it and in the

quiet dignity of Lee contrasted with the gruff magnanimity of Grant, it

somehow lifted a gentle mantle over the years of terrible bloodshed. It

was the symbol the nation craved to reassure it that

it was again whole. As the writer and diplomat James Russell Lowell

said when told that Lee had surrendered at Appomattox Court House, "I

felt a strange and tender exultation. I wanted to laugh and I wanted to

cry, and ended by holding my peace and feeling devoutly thankful. There

is something magnificent in having a country to love."

|

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

Back cover: The Last Salute,

painting by Don Troiani. Photograph courtesy Historical Art Prints, Ltd.,

Southbury, Connecticut.

|

|

|