|

Now a place had to be found for the talks. Lee's staff officer,

Marshall, was sent into the village with an orderly, Private Joshua O.

Johns, to scout a location, while Lee, Babcock, and Babcock's orderly,

Captain William McKee Dunn, followed slowly behind. Upon entering the

town, Marshall met a resident, Wilmer McLean. Asked to help locate a

space, McLean first showed the officer an empty house with no furniture

in it. When Marshall shook his head, McLean shrugged. "Maybe my house

will do!" he said. Marshall liked what he saw and sent his orderly to

direct Lee there. In a fine piece of dramatic irony, McLean had moved

his family to this village in 1863 and purchased the Raine House. The

family's previous home had been Yorkshire Plantation, located near

Manassas Junction, Virginia, the site of major battles in 1861 and

1862.

Lee and Babcock soon arrived. They came into the parlor of the house

and sat down to wait for the Federal commander. Babcock's orderly stood

outside ready to guide Grant to the house once he entered the

village.

Grant's party reached the edge of Appomattox Court House soon after

1:30 P.M. Sheridan and Ord were dismounted and waiting as he

approached.

"How are you, Sheridan?" Grant asked.

"First-rate," Sheridan replied.

"Is General Lee up there?" continued Grant, with a nod toward the

town. Sheridan used his arm to accompany his answer. "There is his army

down in that valley, and he himself is over in that house waiting to

surrender to you."

"Come let us go over," Grant said.

|

GENERAL ALEXANDER'S LAST LINE OF BATTLE. PAINTING BY W. C SHEPPARD. (NPS)

|

|

FEDERAL PROVOST GUARD PHOTOGRAPHED IN FRONT OF THE APPOMATTOX

COURTHOUSE IN THE SUMMER OF 1865. (LC)

|

|

WILMER MCLEAN (NPS)

|

Captain Dunn's presence confirmed that this was the place. Grant

immediately went inside, followed by a small group of officers and one

reporter. Grant and Lee shook hands. The two commanders chatted idly

before Lee reminded Grant of the purpose of this meeting and suggested

that it might be best if the surrender terms could be put in writing.

Grant agreed.

|

MEMBERS OF THE MCLEAN FAMILY SIT ON THE FRONT PORCH OF THEIR

HOUSE IN AUGUST 1865. (LC)

|

He sat down and bent thoughtfully over his order book, a cigar in his

mouth. "When I put my pen to the paper I did not know the first word

that I should make use of in writing the terms," Grant later reflected.

"I only knew what was in my mind, and I wished to express it clearly, so

that there could be no mistaking it."

Grant at last finished his draft, checked it over with his military

secretary, Lieutenant Colonel Ely S. Parker, then handed it over to Lee.

The Confederate general showed no sign of emotion, then laid the note in

front of him and slowly read it.

"In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th

instant, I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of Northern

Virginia on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and

men to be made in duplicate—one copy to be given to an officer to

be designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or

officers as you may designate, the officers to give their individual

paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States

until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander to

sign a like parole for the men of his command. The arms, artillery, and

public property are to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the

officers appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the

side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This

done, officers and men will be allowed to return to their homes not to

be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their

paroles and the laws in force where they may reside."

The word "exchanged" was not in the first draft, but once Lee noted

the omission Grant agreed to add it. When Lee reached the portion that

allowed the officers to keep their side arms and private property he

looked up and remarked it would have a happy effect on the army. After

he finished reading the terms, Lee explained to Grant that the horses in

the C.S. cavalry and artillery service were often privately owned, and

their loss would be a serious blow to the men returning to their farms.

Grant agreed that the terms did not address that matter but said he was

willing to issue orders allowing those who claimed horses or mules to

keep them.

The draft, with Lee's mark for the missing word, was handed to Ely

Parker, who made an ink copy while everyone waited. There were brief

periods of conversation among those present, but the importance of the

occasion made the atmosphere strained. While the final draft of the

terms were being finished, Lee had Charles Marshall draft his official

reply.

"I have received your letter of this date containing the terms of

surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia as proposed by you. As they

are substantially the same as those expressed in your letter of the 8th

instant, they are accepted. I will proceed to designate the proper

officers to carry the stipulations into effect."

A few more moments of conversation ensued during which matters of

prisoner exchange and rations for Lee's men were discussed. Grant now

signed the ink copy of his terms, and Lee signed his letter accepting

them. The notes were exchanged, formalizing the act of surrender. Grant

and Lee rose and again shook hands. Then it was over. The time was about

3:00 P.M.

|

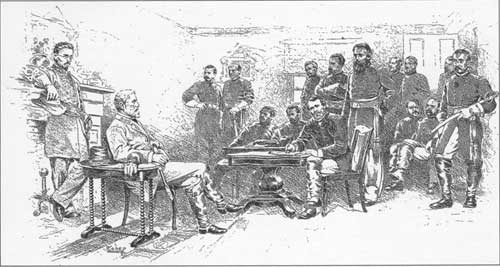

SHOWN IN THIS PERIOD ILLUSTRATION ON THE

SURRENDER ARE L-R: LT. COL. CHARLES MARSHALL, GEN. ROBERT E. LEE, LT.

COL. ORVILLE E. BABCOCK, BRIG. GEN. SETH WILLIAMS, LT. COL. ELY S.

PARKER, LT. COL. THEODORE S. BROWERS, MAJ. GEN. EDWARD ORD, LT. GEN

ULYSSES S. GRANT, LT. COL. HORACE PORTER, BRIG. GEN. JOHN A. RAWLINS,

BRIG. GEN. FREDERICK T. DENT, BRIG. GEN. JOHN G. BARNARD, LT. COL. ADAM

BADEAU, BRIG. GEN. RUFUS INGALLS, AND MAJ. GEN. PHILIP H. SHERIDAN.

(BL)

|

|

LIEUTENANT COLONEL ELY S. PARKER (NPS)

|

Once outside, Lee signaled for his horse and mounted as soon as it

was brought around. According to Horace Porter, who was present,

"General Grant now stepped down from the porch, and, moving toward him,

saluted him by raising his hat. He was followed in this act of courtesy

by all our officers present." Grant then returned inside the house,

where he wrote a series of orders to his forces regarding implementation

of the surrender. So engrossed was he in making certain that all the

necessary instructions had been issued that it wasn't until he left the

McLean house and was riding back toward where his headquarters had been

established that he realized he had not officially notified Washington.

Grant dismounted at once, sat on a large stone alongside the road, and

wrote the following message to be sent to the Secretary of War:

"General Lee surrendered the army of Northern Virginia this

afternoon on terms proposed by myself. The accompanying additional

correspondence will show the conditions fully."

|

THE SURRENDER OF GENERAL LEE

The following account was written by Lieutenant Colonel Charles

Marshall, who served on Lee's staff throughout the war and was present

during the surrender. It was originally published in Century

Magazine.

"The terms of the letter having been agreed to, General Grant

directed Colonel Parker to make a copy of it in ink, and General Lee

directed me to write his acceptance."

|

General Lee said to General Grant that he had come to discuss the

terms of the surrender of his army, as indicated in his note of that

morning, and he suggested to General Grant to reduce his proposition to

writing. General Grant assented, and Colonel Ely S. Parker of his staff

moved a small table from the opposite side of the room, and placed it by

General Grant, who sat facing General Lee. When General Grant had

written his letter in pencil, he took it to General Lee, who remained

seated. General Lee read the letter, and called General Grant's

attention to the fact that he required the surrender of the horses of

the cavalry as if they were public horses. He told General Grant that

Confederate cavalrymen owned their horses, and that they would need them

for planting a spring crop. General Grant at once accepted the

suggestion, and interlined the provision, allowing the retention by the

men of the horses that belonged to them. The terms of the letter having

been agreed to, General Grant directed Colonel Parker to make a copy of

it in ink, and General Lee directed me to write his acceptance. Colonel

Parker took the light table upon which General Grant had been writing to

the opposite corner of the room, and I accompanied him. There was an

inkstand in the room, but the ink was so thick that it was of no use. I

had a small boxwood ink-stand which I always carried, and I gave it,

with my pen, to Colonel Parker, who proceeded to copy General Grant's

letter. When Colonel Parker had concluded the copying of General Grant's

letter, I sat down at the same table and wrote General Lee's answer. I

have yet in my possession the original draft of that answer. It began:

"I have the honor to acknowledge." General Lee struck out those words.

His reason was that it ought not appear as if he and General Grant were

not in immediate communication. When General Grant had signed the copy

of his letter made by Colonel Parker, and General Lee had signed the

answer, Colonel Parker handed to me General Grant's letter, and I handed

to him General Lee's reply, and the work was done. General Grant said to

General Lee that he had come to the meeting as he was and without his

sword, because he did not wish to detain General Lee until he could send

back to his wagons, which were several miles away. This was the only

reference made by any one to the subject of dress on that occasion.

General Lee had prepared himself for the meeting with more than usual

care, and was in full uniform, wearing a very handsome sword and sash.

This was doubtless the reason for General Grant's reference to himself.

At last General Lee took leave of General Grant, saying that he would

return to his headquarters and designate the officers who were to act on

our side in arranging the details of the surrender. We mounted our

horses, which the orderly was holding in the yard, and rode away.

|

THIS PAINTING BY LOUIS MATHIEU GUILLAUME (1816-1892) SHOWS HIS

INTERPRETATION OF THE SURRENDER SCENE INSIDE THE MCLEAN HOUSE. (NPS)

|

|

THIS 1867 LITHOGRAPH OF THE SURRENDER WAS PRODUCED BY

WILMER MCLEAN. (LC)

|

The following account was written by Ulysses S. Grant and is

taken from Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. It was originally

published by Charles L. Webster and Co.

No conversation, not one word, passed between General Lee and myself,

either about private property, side arms, or kindred subjects. He

appeared to have no objections to the terms first proposed; or if he had

a point to make against them he wished to wait until they were in

writing to make it. When he read over that part of the terms about side

arms, horses and private property of the officers, he remarked, with

some feeling, I thought, that this would have a happy effect upon his

army.

Then, after a little further conversation, General Lee remarked to me

again that their army was organized a little differently from the army

of the United States (still maintaining by implication that we were two

countries); that in their army the cavalrymen and artillerists owned

their own horses; and he asked if he was to understand that the men who

so owned their horses were to be permitted to retain them. I told him

that as the terms were written they would not; that only the officers

were permitted to take their private property. He then, after reading

over the terms a second time, remarked that that was clear.

I then said to him that I thought this would be about the last battle

of the war—I sincerely hoped so; and I said further I took it that

most of the men in the ranks were small farmers. The whole country had

been so raided by the two armies that it was doubtful whether they would

be able to put in a crop to carry themselves and their families through

the next winter without the aid of the horses they were then riding. The

United States did not want them and I would, therefore, instruct the

officers I left behind to receive the paroles of his troops to let every

man of the Confederate army who claimed to own a horse or mule take the

animal to his home. Lee remarked again that this would have a happy

effect.

|

A COPY OF MAJOR GENERAL FITZHUGH

LEE'S PAROLE CERTIFICATE. (NPS)

|

|

The word that the fighting was over spread like wildfire among the

troops of both sides. "I never expected to see men cry as they did," a

private in the 12th Virginia recollected, "all the officers cried and

most of the privates broke down and wept like little children and oh,

Lord! I cried too." The mood was, not unexpectedly, decidedly different

on the Union side. "A general jubilee took place," recalled a New Yorker

in the 146th Regiment. "Some of us gave expression to our feelings by

running to an orchard near by and throwing our canteens, haversacks, and

coats into the trees, grabbing each other and rolling over and over on

the ground; some laughed, some cried, all were overjoyed."

|

GRANT'S DRAFT OF THE SURRENDER TERMS. (NPS)

|

As Lee rode toward his headquarters, his passage was slowed by

throngs of his men who crowded near, anxious to be with him at this

emotional moment. One grizzled veteran expressed the mood of many when

he called out, "I love you just as well as ever, General Lee." It was

hours before Lee could disentangle himself from all those who wanted to

talk to him. Then he was alone in his tent, with only his memories and

conscience as company.

An urge for momentos now possessed the men of both armies. The

unfortunate Wilmer McLean was besieged by Yankee officers who made off

with many items from the surrender room. A few tried to assuage their

consciences by forcing a payment upon the reluctant host, but the fact

is that nothing was taken with his willing permission. The apple tree

where Lee had rested while he waited to hear from Grant also paid for

its notoriety. "Our men wanted pieces of wood from the tree under which

General Lee sat," a Pennsylvania soldier explained. "They began breaking

twigs and then everyone wanted a piece of the tree for a souvenir.

Before they finished they had cut down five large trees."

|

THOMAS NAST PAINTING TITLED PEACE IN UNION WAS COMPLETED THIRTY

YEARS AFTER THE SURRENDER. (COURTESY OF GALENA-JO DAVIES COUNTY HISTORY

MUSEUM, ILLINOIS)

|

|

GENERAL LEE AND LIEUTENANT COLONEL MARSHALL LEAVE THE MCLEAN HOUSE

AFTER THE SURRENDER. (ILLUSTRATION BY DON STIVERS, COURTESY OF

STIVERS PUBLISHING)

|

There was a light rain throughout the next day, April 10. Grant had

agreed to supply rations to Lee's hungry men, so the wet air was spiced

with the tang of camp fires as the men cooked the food they had been

given. The despair of yesterday was gradually becoming acceptance and

resignation. A North Carolina soldier observed that the "universal

sentiment was that the question in dispute had been fought to a finish

and that was the end of it."

It was a day filled with incidents both touching and awkward as

former foes met, sometimes as comrades, sometimes as victors and

vanquished. U. S. Grant, with a sudden urge to speak with Lee one more

time, rode toward the Confederate lines a little after 9:00 A.M. Lee was

not expecting the visit, so it wasn't until nearly ten o'clock that he

was able to come out of his lines to meet Grant on a small knoll just

east of the village. Grant hoped Lee would help convince other regions

of the Confederacy to surrender, but Lee demurred, saying he could do

nothing without first consulting President Jefferson Davis. At Lee's

suggestion, Grant agreed to print parole passes allowing former

Confederate soldiers to pass safely to their homes.

|

A REMARKABLE COINCIDENCE

When I first joined the Army of Northern Virginia in 1861, I found a

connection of my family, Wilmer McLean, living on a fine farm through

which ran Bull Run, with a nice farmhouse about opposite the center of

our line of battle along the stream. Confederate General P. G. T.

Beauregard made his headquarters at this house during the first affair

between the armies—the so-called battle of Blackburn's Ford, on

July 18. The first hostile shot which I ever saw fired was aimed at this

house, and about the third or fourth went through its kitchen, where our

servants were cooking dinner for the headquarters staff.

I had not seen or heard of McLean for years, when, the day after the

surrender, I met him at Appomattox Court House, and asked with some

surprise what he was doing there. He replied, with much indignation:

"What are you doing here? These armies tore my place on Bull Run

all to pieces, and kept running over it backward and forward till no man

could live there, so I just sold out and came here, two hundred miles

away, hoping I should never see a soldier again. And now, just look

around you! Not a fence rail is left on the place, the last guns

trampled down all my crops, and Lee surrendered to Grant in my house."

McLean was so indignant that I felt bound to apologize for coming back,

and to throw all the blame for it upon the gentlemen on the other

side.

— General Edward Porter Alexander. Originally published in

The Century Magazine.

|

Lee returned to his headquarters to discover that Charles Marshall

had not yet carried out the order given him late the day before to draft

a farewell statement. Marshall dreaded the task and had found reasons to

delay carrying it out. It wasn't until Lee had directed him into an

ambulance, with a guard to keep distractions away, that Marshall finally

completed the assignment. Lee made some changes, then had it copied for

distribution. The result was "General Order No. 9."

"After four years of arduous service, marked by unsurpassed

courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled

to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.

"I need not tell the brave survivors of so many hard fought

battles, who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented

to the result from no distrust of them.

"But feeling that valor and devotion could accomplish nothing that

would compensate for the loss that must have attended the continuance of

the contest, I determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose

past services have endeared them to their countrymen.

"By the terms of the agreement officers and men can return to

their homes and remain until exchanged. You will take with you the

satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully

performed, and I earnestly pray that a Merciful God will extend to you

His blessing and protection.

"With an increasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to

your country, and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous

considerations for myself I bid you all an affectionate

farewell."

|

A MATHEW BRADY PHOTOGRAPH OF LEE, HIS SON CUSTIS (LEFT) AND

ADJUTANT LIEUTENANT COLONEL WALTER TAYLOR TAKEN SHORTLY

AFTER THE SURRENDER. (LC)

|

Also this day there was a meeting of six officers—three each

Union and Confederate—appointed to implement the surrender. They

gathered at the McLean house, where they worked out the details of the

agreement. The result was a five-point document which specified that a

surrender ceremony would take place (the Confederates wanted to stack

their guns in their camps, but General Grant insisted on a formal

capitulation), allowed for U.S. confiscation of official C.S. government

materials, arranged for the transportation of the "private baggage of

officers," permitted mounted men to retain their privately owned horses,

and established a 20-mile perimeter about the village within which all

armed units were automatically included in the surrender. At Clover Hill

Tavern, the military presses clanked on well into the night to complete

the printing of 30,000 blank parole forms necessary to complete the

surrender processing.

Most of Sheridan's cavalry left that day for Burkeville, while

marching orders were issued for the Second and Sixth Corps. U. S. Grant

departed about noon, riding to Burkeville to catch a train to Petersburg

using the military railroad system, which had been extended to that

point.

"The surrender goes on slowly," a Union telegrapher wrote home on

April 11. "You can imagine what an immense amount of writing has to be

done to issue twenty thousand passes, to make out rolls of each command,

to make inventories of all the artillery, wagons, ambulances, horses,

mules, harnesses, arms, accouterments, ammunition and quartermaster and

commissary stores." Plans also went forward for the surrender ceremony.

The First Division of the Fifth Corps was selected for the honor of

receiving the capitulation, with Brigadier General Joshua L. Chamberlain

in charge. His men were in place by 9:00 A.M., April 12, lined up in the

village along the Stage Road. The Confederate infantrymen soon began

filing out from their camps on the north side of the river into the town

to stack their arms for the last time. (Both the cavalry and artillery

present with the army had already turned in their weapons, the troopers

on April 10 and the gunners April 11.)

|

GRANT'S MESSAGE TO STANTON, APRIL 9, 1865. (NPS)

|

|

GENERAL LEE'S RETURN TO HIS LINES AFTER THE SURRENDER. (BL)

|

Leading the sad infantry procession was Major General John B.

Gordon. He was roused from a deep depression by a gesture of honor

ordered by Chamberlain. As Gordon rode past the leading files of

waiting Federals, he was surprised to hear the shifting of weapons

and looked up to see his former enemies holding their rifles in the

position of "salute." Gordon accepted the gesture and commanded his

troops to return it. "That was done," one observer noted, "and a truly

imposing sight was the mutual salutation and farewell."

It was not until nearly 4:00 P.M. that the last Confederate troops

had finished stacking their arms and folding their regimental flags.

Before that time, Robert E. Lee, with a small personal escort, left for

Richmond. Some of the veterans who saw him ride off ran down to the

roadside where they waved their hats and shouted, "Goodbye General,

goodbye."

|

|