|

The rainy morning of April 5 promised a gloomy, dispiriting day for

Confederate fortunes, a prognosis that events soon confirmed. The

quartermaster details began to return from their foraging expeditions,

empty-handed for the most part. There was simply no food to be had in

this region. Lee wasted little time on self-recriminations and issued

orders to resume the retreat. The path now would be southward, toward

Burkeville and North Carolina. Even as the hungry columns began to march

along the railroad line, the surplus artillery and supply wagons

lumbered off to the west to make a wide circle around the army's right

flank, beyond the reach of the Yankee cavalry. Behind them rumbled the

ominous sounds of explosions as the artillery stocks that could not be

transported were destroyed.

There was more bad news. The first concerned the supply train that

had come out of Richmond with Ewell's command. It too had been sent on a

circuitous route to allow the foot soldiers the more direct way, and

after struggling along the wearying course of muddy roads and swollen

streams, it had successfully reached a point

just seven miles northwest of Amelia Court House at Paineville. There it

had been struck by a force of bluecoated cavalry and virtually wiped

out. A rapid response by the Confederate cavalry posted nearby had badly

punished the raiders, but serious damage had been done. There had been

desperately needed supplies on that wagon train that were now

destroyed.

Lee's gamble to concentrate and

provision the army before the Federals could cut off its route south had

failed.

|

About 1:00 P.M. Lee himself rode down the rail tracks to check on the

progress of the march. Just outside Jetersville he found the leading

files drawn up in order of battle and halted. A quick personal

reconnaissance revealed only too clearly the fresh earthworks and

defiant battle flags of the enemy drawn in a line squarely across his

path. Lee's gamble to concentrate and provision the army before the

Federals could cut off its route south had failed. An artillery officer

with Lee remembered that the Confederate commander had never before

seemed "so anxious to bring on a battle . . . as he seemed this

afternoon," but the Union troops were too well posted.

The loss of this option seemed to befuddle Lee, who, in the words

of his capable corps commander James Longstreet, "hesitated as to his

course." At last the decision was made to shift the army's course from

south to west so that the men might reach a still usable stretch of the

South Side Railroad and there obtain supplies from Lynchburg. No local

guides could be found to direct this new course so Lee had to rely on

his maps. A soldier in the ranks who saw him at this time described

Lee's countenance as "very serious."

|

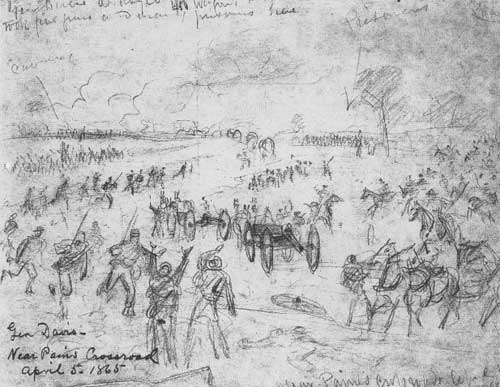

THE SKIRMISH NEAR AMELIA COURT HOUSE AS SKETCHED BY ALFRED WAUD. (LC)

|

Even as Lee was pondering this change of plan, the Yankees south of

Jetersville were being heavily reinforced. The first elements of the

Second and Sixth Corps began to arrive around 2:30 P.M. and immediately

went into position alongside the Fifth Corps and the cavalry. Hours

before this happened, Sheridan had sent out a full mounted brigade on a

sweep around the enemy's western flank to determine if the Rebels were

retreating that way. It was this force that came upon the virtually

unguarded Richmond wagon train near Paineville and wrecked it in an orgy

of sabering, pistoling, and arson. Recalled a New York trooper in those

ranks, "After sending the plunder on the road to Jetersville, the boys

were reminded that there was some of the Confederate cavalry still

alive, as a vigorous attack was made on their rear."

The intelligence that Lee's wagons were moving west, not south,

convinced Sheridan that Lee's infantry would soon follow suit. It was an

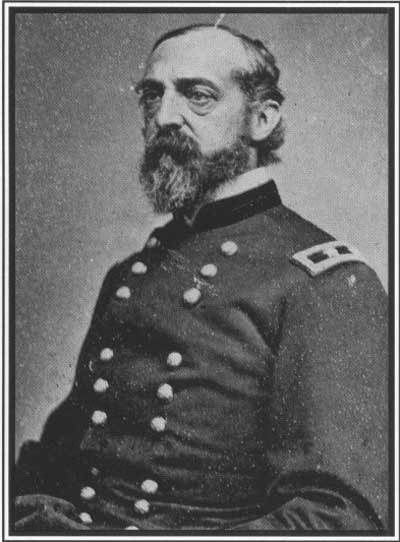

opinion not shared by the ranking officer on the field, George G. Meade,

who believed that Lee meant to make a stand at Amelia Court House. The

Army of the Potomac commander made his dispositions accordingly, with

the intention of enveloping the position from the south and east the

next day. Unable to change Meade's mind, Sheridan decided to go over his

head by sending a message to U. S. Grant asking him to come to

Jetersville at once.

The courier did not reach the lieutenant general (who was traveling

with Ord's columns) until well after dark, but Grant at once set off

cross country, accompanied only by a small escort. He reached Sheridan

shortly after 10:30 P.M., then the two went over to see Meade. The plans

were changed, and when daylight came the army would advance directly on

Amelia Court House.

The Army of Northern Virginia needed a few breaks if it were to

survive much past the night of April 5. It got a few, but they were

mostly bad ones. Speed was the life or death factor now, something that

proved impossible to attain. The few roads that wriggled west from

Amelia Court House were simply not sufficient to absorb the many men and

wagons under these conditions. Added to that, the wreckage from the

wagon train ambushed near Paineville and the generally poor condition of

the stream crossings conspired to turn this night march into a

stop-and-go nightmare.

|

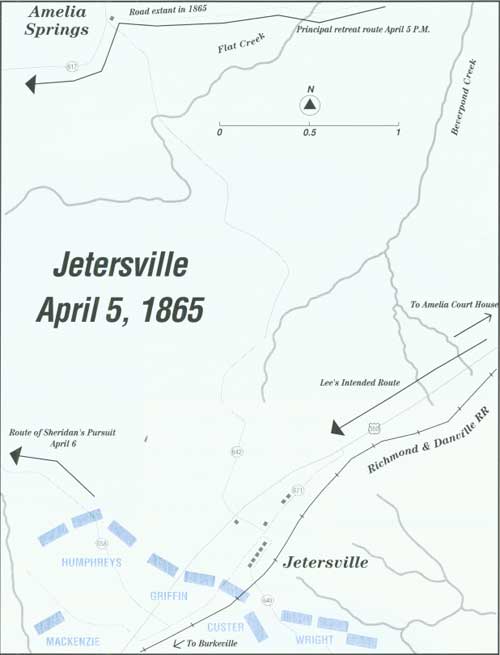

LEE BLOCKED

Lee expected to resupply his men at Amelia Court House and then to

follow the Richmond and Danville Railroad into North Carolina. But his

orders for rations to be waiting for him at Amelia were lost. Lee spent

24 hours in a futile attempt to gather supplies, losing what little lead

he had gained over Grant's forces. When Lee turned south on April 5, he

found that he was blocked at Jetersville. In no condition to fight, Lee

moved his weary army west.

|

As if Lee needed any further reason for urgency, he received from

General Gordon a dispatch found on two "Jessie Scouts" who had been

taken while masquerading as Confederates. The note, from U. S. Grant to

E. O. C. Ord, confirmed a strong Federal presence in Jetersville. (In a

message accompanying the captured document, Gordon asked if he was

expected to shoot these men as spies. "Tell the General," Lee replied,

"the lives of so many of our men are at stake that all my thoughts now

must be given to disposing of them. Let him keep the prisoners until he

hears further from me.")

|

CAPTURE OF A CONFEDERATE WAGON TRAIN NEAR PAINEVILLE. (LC)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE G. MEADE (LC)

|

If things were bad at the beginning of this desperate night march,

they became even worse at daylight, April 6. For the first few miles

west of Amelia Court House, Lee's men had been able to pick up time by

moving along a series of parallel roads. But once beyond Deatonville

there was only a single track for the men, wagons, and animals to

follow. Lee expected that the hit-and-run Yankee riders would reappear

on his left flank at dawn, but other than issuing orders for the long

files to keep closed up, there was little he could do. As the various

commands were funneled onto the single road past Deatonville, the order

of the march became, first Longstreet's Corps (made up of the First and

Third Corps), followed by the commands of Anderson, Ewell and Gordon,

with most of the wagons between the last two.

Lee rode ahead to the goal of this day's movement, Rice's Station on

the South Side Railroad. He was there when Longstreet's men began to

arrive during the morning, followed by three divisions once under the

late A. P. Hill but now reporting to the First Corps commander. Then,

ominously, the steady flow of men dropped to a trickle. Lee spent the early

afternoon preparing defensive positions against Federals advancing west

from Burkeville and getting things in order for the next day's march. He

then nervously rode back along the route to determine what was holding up nearly half of his

army.

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL ULYSSES S. GRANT AND HIS STAFF AT CITY POINT, VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

|

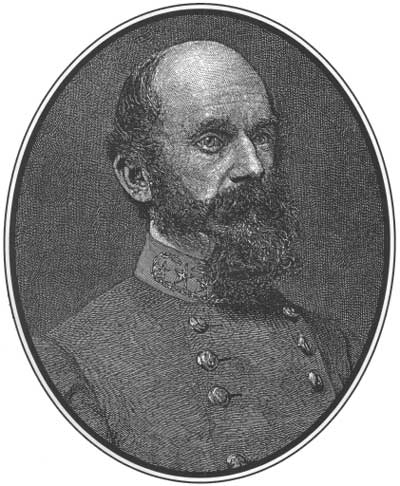

LIEUTENANT GENERAL RICHARD S. EWELL (BL)

|

The three Union infantry corps at Jetersville began a slow advance

toward Amelia Court House around 6:00 A.M., while most of Sheridan's

cavalry galloped off to the west. Explained General Meade's aide,

Theodore Lyman, "We did not know just then, you perceive, in what

direction the enemy was moving." By 9:00 A.M. it was clear that the

entire Rebel force had shifted west, toward Deatonville. The pursuit was

immediately resumed, with the Second Corps (under Major General Andrew

A. Humphreys) pressing the enemy rear guard, supported by the Fifth

Corps. The Sixth Corps (commanded by Major General Horatio Wright) moved

to follow the cavalry, which was thrusting ahead with a cocky

aggressiveness. "Today will see something big in the crushing of the

rebellion," one of Sheridan's brigadiers, Charles H. Smith,

predicted.

The situation was well-suited to the quick-moving cavalrymen armed

with fast-firing breech-loading weapons. The Confederate march was

strung out along a single road, with weary groups of foot soldiers

trying to watch over miles of lumbering wagons. Time and again small

parties of bluecoated riders would dash at an exposed section of

vehicles, shooting horses and drivers and raising general havoc before

the security units could react to drive them off. And these attacks were

not always small ones. Near a road intersection known variously as

Holt's or Hotts Corner, Brigadier General Charles Smith led most of his

brigade in a charge on the Rebel column but met the massed rifles of

Richard Anderson's corps and was repulsed. This action forced Anderson's

men to halt, however and by the time they resumed the march the gap

between them and the units preceding them under Longstreet had widened

to an alarming degree. And during the time Crook had been keeping

Anderson occupied, other mounted units were moving into that gap to cut

the road.

|

MAJOR GENERAL HORATIO G. WRIGHT (BL)

|

Once Anderson's command cleared the crossroads, it continued toward

the crossing of Little Sailor's Creek from where it would proceed to

Rice's Station. Behind Anderson came Ewell's mixed command drawn from

the Richmond defenses, then the hulk of the wagons, and finally Gordon's

Corps, which had its hands full fending off General Humphreys's hot

pursuit. "On and on, hour after hour, from hilltop to hilltop, the lines

were alternately forming, fighting, and retreating, making one almost

continuous shifting battle," Gordon recalled. Then Ewell learned from

the cavalry commander Fitzhugh Lee that the Yankees had gotten in front

of Anderson, bringing his corps to a halt.

|

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN B. GORDON (LC)

|

Ewell now made a fateful decision. He ordered the supply wagons to

turn off the main route at Holt's Corner, to follow a trail leading off to the

northwest, which eventually reconnected with roads to Rice's Station.

Although he never issued Gordon any formal instructions to stick with

the wagons, that is what Gordon did, turning his corps to follow. Ewell's

men, in the meantime, took up a defensive position (facing east and

northeast) along the high ground on the west side of Little Sailor's

Creek.

The Federal Second Corps never broke contact with Gordon's men and

also turned northwest at Holt's Corner. But the roads behind Humphreys's

men were quickly filled with troops from Wright's Sixth Corps, which had

come up from the south in support. These soldiers, now pushing after

Ewell, were soon lining the high ground east of Little Sailor's Creek.

The effect of all this was to place Anderson's and Ewell's commands

virtually back-to-back, with Yankee cavalry before Anderson and Union

infantry confronting Ewell. The Confederates were boxed in, neat and

simple. "The odds against us were fearful," recalled a Virginia Rebel

named R. S. Rock.

Ewell had no artillery with him and so was unable to reply when, at

5:15 P.M., a row of 20 Yankee cannon lined up along the ridge opposite

his position opened a concentrated fire that lasted for more than 30

minutes. A Maryland officer on the receiving end of the barrage recalled

the "shot sometimes plowing the ground, sometimes crashing through the

trees, and not infrequently striking in the line, killing two or more at

once." Behind the curtain of powder smoke Federal battle lines took

shape. At 6:00 P.M. the guns fell silent and the infantry formations

began to advance.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

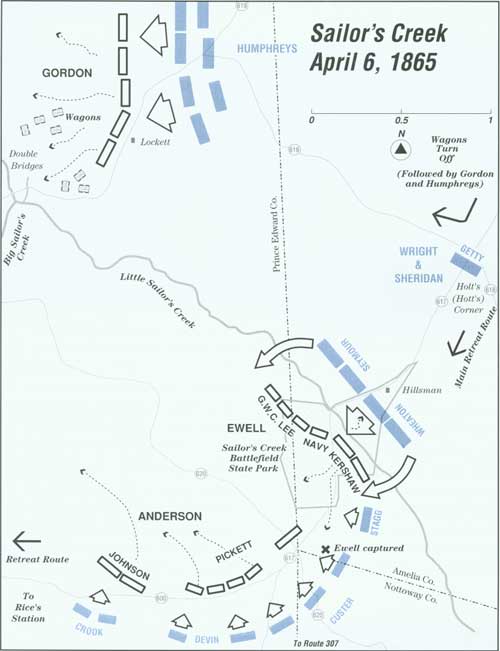

A CATASTROPHIC DEFEAT

Harassed on its flanks by Sheridan's cavalry, and pressed heavily by

Federal infantry under Wright and Humphreys, Lee's retreating column

began to lose cohesion. A fatal gap opened between the more quickly

moving head of the column under Longstreet and the tail under Anderson,

Ewell and Gordon. Sheridan's horsemen exploited the gap to cut off

Ewell, who took a position along Little Sailor's Creek. Further north,

Gordon was able to break contact with Humphreys, though he lost many

valuable supply wagons. Ewell was attacked by Wright whose men

overwhelmed the Rebel force after brief but bitter combat. Approximately

8,000 Confederates, including eight generals, were killed, wounded or

captured. Said Lee, "A few more Sailor's Creeks and it will be over."

|

Up to this time Richard Anderson had successfully beaten back several

small-scale attempts by Sheridan's cavalry to burst through his

position. Sheridan's response was to put more muscle into the effort. He

organized a combined charge by the divisions under Brigadier General

Thomas C. Devin and Brevet Major General George A. Custer. An awestruck

onlooker later wrote, "The fire as they neared the rebel line was

terrific, opening gaps in their lines, but if a horse was shot & the

rider unhurt he would jump up [and] take his place, firing as he went."

With a last rush, the troopers were in among the Confederate defenders.

"The scene at this time was fierce and wild," a West Virginia trooper

named F. C. Robinson recalled, "but the saber, revolver and Spencer

carbine of the cavalry were too much for the bayonet, and the musket

that could not be quickly loaded."

Anderson's left flank was overwhelmed and his center collapsed by the

force of this assault. The defense simply disintegrated (one Federal

trooper later wrote of the sight of Confederate soldiers "scattering

like children just out from school"), though several units did leave the

field under discipline. Of the 6,300 or so men Anderson marched into

this fight, nearly 2,600 were killed or captured, mostly the latter.

Even as the fight along Little Sailor's Creek was moving toward its

climax, the collapse of Anderson's command meant that Ewell's best

escape route was closed.

|

CUSTER PREPARES FOR A CHARGE AT SAILOR'S CREEK. (LC)

|

A few miles north of where all this was taking place, disaster was

also catching up with the main supply train which Ewell had shunted away

in an effort to save it. This detour took the wagons, followed by

Gordon's corps, followed closely by Humphreys's corps, to the eastern

edge of a long valley, at the base of which ran Sailor's Creek. A set of

two successive bridges (known as the "Double Bridges") proved unable to

handle the volume of traffic, causing the wagons to jam up in the nearby

lowland. Gordon's men took up a defensive line along the eastern rim of

the valley in the hope of holding it long enough for the wagons to

escape, but the Federal soldiers would not be denied. In a terribly

short time, Gordon's troops were shoved off the ridge. Battered

infantrymen fell back among the wagons, where chaos reigned for a while,

with fighting men intermixed with frantic teamsters and terrified

animals. By the time Gordon was able to extract his command and position

it astride the west side of the valley, he had lost nearly 2,000 men,

along with three cannon, 200 wagons, and 70 ambulances.

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL RICHARD H. ANDERSON (BL)

|

Back along Little Sailor's Creek, it seemed for a few brief minutes

that Ewell's beleaguered command might be able to stave off the enemy.

The center of the attacking Federal line, outdistancing the flanking

wings, charged unsupported up the hill. It became the concentrated

target of Confederate rifle fire from both front and flank, reeled back

in a panic, and was even chased by a small Rebel force led by Major

Robert Stiles. The retreating Yankees got far enough ahead of their

pursuers to unmask the cannon lined along the creek bank, and a

hellstorm of canister and shrapnel blanketed the impetuous Confederates,

who pulled back.

|

THE SURRENDER OF EWELL'S MEN AT SAILOR'S CREEK AS DEPICTED BY

ALFRED WAUD. (LC)

|

By now the flanking Union regiments had overlapped both ends of

Ewell's line and the whole thing began to fold in on itself. A few

Confederate units (most notably, the Naval Battalion) fought with

desperate ferocity, but the end was inevitable. Ewell himself

surrendered to a sergeant from the 5th Wisconsin near Swep Marshall's

house. Also entering captivity were nearly 3,400 of the approximately

5,300 men he commanded. Counting all the troops engaged along or near

Sailor's Creek this day (Ewell's, Gordon's, and Anderson's), Lee's

losses totaled approximately 8,000. The Federals later reported

casualties of about 1,200. In his brief report of the victory at

Sailor's Creek, Sheridan told Grant, "If the thing is pressed I think Lee

will surrender."

|

THE ADVENTURES OF PRIVATE EDDY

Bell Irvin Wiley, in his classic volume, "The Life of Billy Yank,"

wrote that "of the countless feats of individual valor cited in official

records, none was more remarkable than that of Private Samuel E. Eddy of

the Thirty-seventh Massachusetts Regiment...."

Eddy was a blacksmith and woodturner by trade until finally the

clouds of war beckoned his service to the Union on July 20, 1862, in

Company D. He passed through most of his regiment's fighting relatively

unscathed until April 6, 1865, during Lee's retreat from Richmond and

Petersburg.

While the Confederate army was marching toward the town of Farmville,

it passed over a series of water courses that emptied into the

Appomattox River. One was known locally as Little Sailor's Creek. While

the line of march of the Southerners was crossing this small stream,

Union troops from the 6th Corps (of which the 37th Massachusetts was

part) intercepted them at this point. In command of the immediate

Confederate forces was Gen. Richard S. Ewell who had with him units

under Gen. George Washington Custis Lee, Gen. Joseph Kershaw's division

and a small group of marines and sailors.

As two divisions of Union Gen. Horatio Wright's 6th Corps arrived on

the scene, preparations were made to do battle with the Southerners, who

were dug in on the opposite high ground overlooking the creek. After

nearly half an hour of artillery bombardment on the exposed Confederate

troops, the Union soldiers moved down to and across the creek, then

formed to begin their assault on Ewell's position. As this was

transpiring, one of Eddy's colleagues remembered that "Private Eddy was

obliged to fall from the ranks, being about 44 years of age, and having

been wounded in the knee March 25 previous—less than two weeks

previous. To the surprise of his officers and comrades, he found the

regiment and joined it...."

In their initial approach upon the enemy line, the Union troops were

received by an impromptu counterattack by Custis Lee's men. Deadly

hand-to-hand fighting took place as the two sides came together. Some of

the Northern regiments were forced back to the creek, while others, like

the 37th Massachusetts, held their ground. Under the fire of artillery

again, the Confederates fell back to their slight breast-works. Finally,

the Union soldiers reformed and began their ascent once more, this time

overlapping the flanks of the Southern position. Though brief in time,

both armies struggled desperately before Ewell's men began to surrender.

Gen. Custis Lee is said to have given his sword to a member of the 37th.

It was during this time that Sam Eddy had his ordeal.

The colonel of the 37th, Oliver Edwards, remembered that:

"The Colonel next in command (of Lee's forces) was in the act of

handing his sword to adjutant (John S.) Bradley, when, seeing how small

was the command (300 men) opposed to him, he drew back his sword, and

attacked the adjutant with his pistol. Bradley grappled with his foe

though wounded by his pistol shot (passing near his shoulder

blade)—and they rolled into a hollow, where surrounded by rebels,

Bradley was shot through the thigh, when Samuel E. Eddy private Co. D.

shot the rebel Colonel as he was about to shoot Bradley through the head

with his pistol. A rebel who saw the man who killed his Colonel—put

his bayonet through private Eddy's body, the bayonet passing through the

lung and coming out near his spine. Eddy dropped his gun, and tore the

bayonet out from his body, then in a hand to hand struggle with his foe

temporarily disabled him and crawled to his gun, and with it killed his

antagonist."

William Shaw, also of the 37th, remembered:

"I saw him (Eddy) after the battle sitting on the ground. I says to

him are you wounded? He said they have run a bayonet through me. I

looked and saw where it entered his body and came out on his back. He

said it did not hurt so very much when it went through, but the man

twisted it when withdrawing it but the man never bayoneted another

soldier, for Mr. Eddy was so indignant, that he shot him then and

there."

Sam Eddy's war service was over. Initially taken to a nearby field

hospital on the battlefield, he eventually was transferred to a larger

hospital at Burkeville Junction. A few days later he was sent by train

and placed in the Depot Field Hospital in City Point where he

recuperated from his wound. His treatment was for a bayonet wound in the

breast with the weapon entering between the third and fourth ribs and

passing through near the spine. He was mustered out June 9, 1865.

Because of his heroism in saving the life of Adjutant Bradley,

Private Eddy in 1897 would be issued a Medal of Honor for gallantry at

the Battle of Little Sailor's Creek. On March 7, 1909, the old Civil War

veteran passed on and was buried in Chesterfield, Mass.

|

|

|