|

THE CAMPAIGN FOR ATLANTA

"God help my country!" So wrote Mary Chesnut of South Carolina in her

diary on New Year's Day 1864: She expressed the feeling of the vast

majority of her fellow Southerners. Their expectation of victory, so

high at the beginning of 1863, had by the end of that year been

transformed into a dread of impending doom by the disastrous defeats at

Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. Powerful Northern armies now

dominated vast areas of the South and stood poised to overrun still more

against badly depleted Confederate forces. The South's economy was close

to collapse, thousands of its people were homeless refugees, its

ramshackle rail system barely functioned, the Northern blockade was

growing evermore effective, and any chance that Britain would recognize

and aid the Confederacy had disappeared with the Emancipation

Proclamation and the failure of Robert E. Lee's second invasion of the

North at Gettysburg.

|

MARY CHESNUT (NA)

|

Yet, in spite of all of this, the South retained, as 1864 got under

way, one last hope of victory. Paradoxically, this hope came from the

North. There the Democratic party contended that the nation never could

be reunited by war but only through peace, a peace to be achieved by

giving the seceded states an opportunity to return to the Union with the

same rights—among them the right of slavery—that they had held

when they left it. Accordingly, the Democrats based their strategy,

which they made no attempt to conceal, for the North's 1864 presidential

election on two assumptions: (1) that notwithstanding their 1863

setbacks the Confederates would be able to defy all efforts to subdue

them through the spring, summer, and fall of 1864; (2) that as a

consequence war-weary Northern voters, realizing the futility of trying

to suppress the rebellion by military means, would repudiate the pro-war

and antislavery policies of the Republicans by replacing Abraham Lincoln

in the White House with a Democrat pledged to a suspension of

hostilities and the negotiation of a voluntary restoration of the

Union.

|

WALTER TABER ILLUSTRATION OF CONFEDERATE GUNNERS DURING THE BATTLE OF

ATLANTA. (COURTESY OF AMERICAN HERITAGE PRINT COLLECTION)

|

The assumptions of the Democrats gave Southerners their hope of

victory in 1864. They believed that if they could hold out long and well

enough against the Yankee armies they would break the will of the North

to go on with the war and so open the way for the Democrats to take

power in Washington, an event that would lead—not to the South

returning to the Union, for it had fought too hard and suffered too much

to do that—but rather to Northern acceptance of Southern

independence: once the North stopped the war it would be impossible for

it to resume it.

|

BY 1864, THE UNION HAD FOUR TIMES AS MANY SOLDIERS AS THE SOUTH. THESE

MEN OF THE 125TH OHIO FOUGHT GALLANTLY DURING THE ATLANTA (USAMHI)

|

What brought hope to Southerners inspired fear among Republicans.

They too realized that should the Federal armies be bogged down in

stalemate come election time, the North indeed might turn to the

Democrats with their specious but seductive promise of Union through

peace. To prevent this from happening it would be necessary either to

defeat the Confederacy before the voters went to the polls in the fall

or else to score such military successes as to convince the majority of

those voters that victory was on the way. That was why on February 1,

1864, Lincoln issued a call for 200,000 more troops in addition to the

300,000 he had summoned to the colors in October: these 500,000 new

soldiers would be twice the number the Confederacy could muster

altogether. It also was why Lincoln on March 9, 1864, appointed Ulysses

S. Grant to the newly created rank of lieutenant general and placed him

in command of all Union armies. If Grant, who had captured whole Rebel

armies at Fort Donelson and Vicksburg and routed another at Chattanooga,

could not lead the North to victory in 1864, who could?

Such, then, were the grand strategies of North and South as the war

entered its fourth year. In the case of the South, it sought to win by

not losing, in the hope that the North, finding itself unable to win,

would lose its will to continue the war. As for the North, Lincoln and

the Republicans needed and therefore would endeavor to win by winning,

thus maintaining the support of the Northern people for the war and for

themselves. Which strategy prevailed and which failed would be decided

on the battlefields.

|

GENERAL JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON (USAMHI)

|

If the South was to win by not losing, there were two places where it

was absolutely essential to deny the North victory: Virginia and

Georgia. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was confident that Lee

could hold the Yankees at bay in Virginia, preventing them from taking

Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy and the symbol of its

independence.

He lacked the same confidence in General Joseph E. Johnston,

commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee in north Georgia. He

considered Johnston to be vain and selfish as a man and as a general

more inclined to retreat than to fight, to defend rather than to attack,

and so recalcitrant in implementing the wishes of the government with

regard to military operations as to border on the insubordinate.

Therefore, he had appointed Johnston to command the Army of Tennessee,

following its debacle at Chattanooga in November 1863, most reluctantly

and solely because no other general of the requisite rank was available

who could be depended on to do better or even as well. He could only

hope that Johnston, now that the fate of the Confederacy hung in the

balance, would be more cooperative, more aggressive, and above all more

successful than he hitherto had been.

It would be a vain hope. Johnston's dislike and distrust of Davis

matched, indeed exceeded, the president's dislike and distrust of the

general. Johnston knew, too, that Davis had named him to head the Army

of Tennessee out of necessity, not preference, and suspected that Davis

would not be altogether unhappy should he fail in that post.

Accordingly, although he would do his best, by his lights, to defend

Georgia, as always he would take care while doing so to preserve his

public reputation for high military skill, a reputation that literally

was more precious to him than life itself.

How difficult it was for Davis and Johnston to work in harmony became

evident from the start. Soon after Johnston took command of the Army of

Tennessee at Dalton, Georgia, on December 27, 1863, he received a letter

from the president urging him to attack and defeat the Federal army at

Chattanooga, thereby forestalling an invasion of Georgia by delivering

what in effect would be a pre-emptive strike. In theory it was a good

plan but in fact utterly impracticable. As Johnston promptly and

correctly pointed out in reply, the Army of Tennessee lacked the

strength, supplies, and transport to conduct a successful offensive. The

only way it could reasonably hope to do so, Johnston argued, was to

repel the Federals when they attacked, then launch a counterattack. To

that end he asked that he be reinforced by Lieutenant General Leonidas

Polk's army in Mississippi and Alabama.

Davis, who had received contrary information from other sources,

refused to believe Johnston's assessment of the Army of Tennessee's

offensive capability. To him it seemed that Johnston was being his usual

uncooperative and unaggressive self. Hence for the next four months he

endeavored to persuade Johnston to go after the Yankees before the

Yankees came after him. Just as persistently Johnston refused to do

anything of the kind. Since Davis, for political reasons, dared not

remove Johnston or order him to attack, by default Johnston's strategy

for meeting and defeating the Union invasion of Georgia became the

Confederate strategy.

|

GENESIS IN STEEL: RAILROADS BUILD A CITY

More than any other Southern city that flourished before the Civil

War, Atlanta was a creation of the railroad. It lay perfectly

uninhabited in 1840, when survey crews began marking the location of

three rail lines that would connect there. The Georgia Railroad extended

from Augusta to the east, while the Macon & Western worked its way

up from the south. These lines led into the wilderness from the more

populated coast, but a third railroad, the Western & Atlantic,

snaked its way south through the mountains from Chattanooga, on the

Tennessee border. Engineers opted to join these roads a few miles south

of the Chattahoochee River, and they named this arbitrary junction

"Terminus." Colonel Stephen Long, the chief engineer of the Western

& Atlantic, reportedly refused a chance to buy 200 acres in Terminus

because he doubted the place would ever amount to anything.

In 1843 the site was incorporated under the name of Marthasvllle. Two

years later its name was changed again, to Atlanta. Colonel Long's

disdained 200 acres formed the center of the city, which blossomed

rapidly. By 1860 Atlanta could boast a population of more than 10,000,

and it was still growing.

The city was recognized early in the war as a vital link in

Confederate communications. The Western & Atlantic Railroad, in

particular, served as an umbilical between the Upper South and the Deep

South, connecting with the equally important rail center at Chattanooga,

about 140 miles to the north. As early as April of 1862 Union

authorities had attached enough significance to the Western &

Atlantic that Federal soldiers infiltrated northern Georgia in civilian

clothing and stole a locomotive with the intention of cutting the line.

That incursion ended in disaster, as did Union Colonel Abel Streight's

cavalry raid in the spring of 1863, which culminated in the capture of

Streight's command by Confederate cavalry under General Nathan Bedford

Forrest.

|

TRAIN SHED IN ATLANTA. (LC)

|

The Western & Atlantic proved even more crucial as a supply line

as Federal armies pushed the Confederate Army of Tennessee eastward in

the summer of 1863. When Union troops occupied Chattanooga and Knoxville

that fall, however, they interrupted all rail traffic north of Dalton,

Georgia. The Western & Atlantic thereafter ceased to hold its former

strategic value for the South: as 1864 opened, the only major rail link

between the two major Confederate armies was the overburdened coastal

route.

Atlanta itself remained vital to the Confederacy, despite the

diminished importance of the Western & Atlantic. The city still

served as a terminus for three rail lines that led to the unoccupied

portions of the besieged nation, and it rivaled Richmond in its

industrial importance to the South. Its railroad heritage had spawned

machine shops, mills, and foundries that supplied demands from

Mississippi to the Carolinas, and if it were lost those demands would be

thrown upon the distant Richmond factories that were already falling

behind in production, from which goods would have to be transported

hundreds of additional miles over railroads that were already too

taxed.

As William Sherman's troops prepared to move south in the spring of

1864, Atlanta had doubled in population as its industrial base expanded

to support the machinery of war. Warehouses bulged with materiel for the

Army of Tennessee, while trains steamed hourly out of the city to the

east, west, and south with military or mechanical provisions and

equipment. Meanwhile—just in case—Confederate engineers were

putting the finishing touches on a series of artillery redoubts and

rifle pits that partially surrounded the city.

—William Marvel

|

While Johnston and Davis wrangled, Grant formulated a plan for

winning the war for the North.

|

While Johnston and Davis wrangled. Grant formulated a plan for

winning the war for the North. Basically it called for Grant, who had

decided to take personal charge of operations in Virginia, to smash Lee

and/or take Richmond, and for the Union forces at Chattanooga to crush

Johnston and/or take Atlanta, a vital railroad and manufacturing center

with a strategic and symbolic importance second only to that of

Richmond. Should either city fall, then it would merely be a matter of

time before the Confederacy itself fell—and both Northerners and

Southerners realized this.

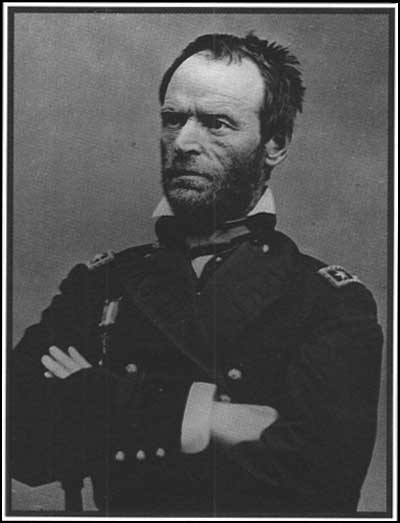

To conduct the campaign against Johnston and Atlanta, Grant chose

Major General William Tecumseh Sherman. His choice was based on

friendship, not on Sherman's generalship. So far that had not been

impressive. Early in the war, while commanding in Kentucky and Missouri,

Sherman has so greatly exaggerated the strength of and danger from the

enemy that he had suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be relieved.

Returned to duty, he went to the opposite extreme by denying that the

Confederates posed any threat at all, with the result that he was

primarily to blame for the surprise and near destruction of Grant's army

at Shiloh. In December 1862 his assault at Chickasaw Bluffs in

Mississippi failed terribly, and during the subsequent Vicksburg

campaign, although he ably did all that Grant told him to do, in truth

he did not have to do very much. Assigned by Grant the starring role in

the Battle of Chattanooga, his performance was so inept that only an

impromptu attack by the troops of Major General George H. Thomas's Army

of the Cumberland saved Grant from defeat and gave him victory.

|

TWO BRIGADES OF THE FEDERAL IV CORPS TRAIN NEAR CHATTANOOGA. (USAMHI)

|

Yet, despite this lackluster record, Grant deemed Sherman to be the

best man to command in the West while he himself commanded in the East.

He admired Sherman's brilliant intellect, boundless energy, and

persistent enter rise. Above all he knew that Sherman was totally

devoted to him personally and so could be trusted to make every effort

to assist him in defeating the Confederacy in 1864.

On April 4,1864, Grant sent Sherman his instructions. He was to "move

against Johnston's army, to break it up, and get into the interior of

the enemy's country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can

against their war resources." The specific method by which Sherman

accomplished this assignment, Grant added, he left to him, but he did

ask Sherman to submit a broad "plan of operations." This Sherman did on

April 10. After defining his mission as being to "knock Jos. Johnston,

and to do as much damage to the resources of the enemy as possible,"

Sherman stated that he would compel Johnston to retreat to Atlanta,

whereupon he would use his cavalry to cut the railroad between that city

and Montgomery, Alabama, then "feign to the right, but pass to the left

and act against Atlanta or its eastern communications, according to

developed facts."

|

MAJOR GENERAL WILLIAM T. SHERMAN (LC)

|

|

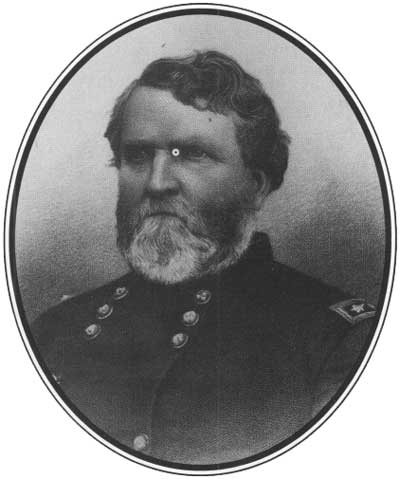

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE H. THOMAS (BL)

|

Superficially Sherman's plan seemed to comply with Grant's

instructions. Actually it did not. Contrary to the clear implication of

those instructions, Sherman proposed to make the capture of Atlanta and

not the destruction of Johnston's army his prime objective. Several

reasons, among them Sherman's personal distaste for battles with all of

their uncertainties, explain this reversal of priorities, but the main

one was that Sherman assumed that it would not be necessary for him to

defeat Johnston because Grant soon would win the war by defeating Lee.

Consequently, Sherman conceived his main task to be that of assuring

Grant's success by preventing Johnston from sending reinforcements to

Lee.

Grant took the same view of the matter. When he replied on April 19

to Sherman's April 10 letter he emphasized the need to forestall

Johnston from aiding Lee. "If the enemy on your front," he cautioned

Sherman, "shows signs of joining Lee, follow him up to the full extent

of your ability."

To "knock Jos. Johnston" Sherman assembled at and near Chattanooga

about 110,000 troops. By far the largest portion of them, nearly 65,000

infantry and artillerists, belonged to Major General George H. Thomas's

Army of the Cumberland, which consisted of three corps: the IV, XIV, and

XX, headed respectively by Major Generals Oliver Otis Howard, John M.

Palmer, and "Fighting Joe" Hooker, who as commander of the Army of the

Potomac in Virginia had come to grief against Lee at Chancellorsville in

May of 1863. Thomas, because of his massive build, gave some the

impression of being slow, and he was called the "Rock of Chickamauga"

because of his stalwart defensive stand at that battle; yet his mind

moved with lightning speed and at Nashville in December of 1864 he would

deliver the most devastating attack of the entire war. On the basis of

both record and talent he, not Sherman, deserved to command the campaign

in Georgia, but he lacked what Sherman so amply possessed: the

friendship and trust of Grant.

|

MAJOR GENERAL GRENVILLE M. DODGE (LC)

|

The next largest part of Sherman's host was Major General James B.

McPherson's Army of the Tennessee (the Federals usually named their

armies after rivers, hence the Army of the Tennessee, whereas

Confederate practice was to name armies after states or portions

thereof, thus the Army of Tennessee), about 23,000 soldiers organized

into Major General John A. "Black Jack" Logan's XV Corps and the

two-division XVI Corps and the two-division XVI Corps of Major General

Grenville M. Dodge. It was Sherman's favorite army, for until recently

he had commanded it, as had Grant before him. McPherson, its new

commander, was intelligent and conscientious but, as events would

reveal, deficient in initiative and enterprise.

Least among the major components of Sherman's invasion force was the

so-called Army of the Ohio. Although Major General George Stoneman's

cavalry division nominally formed part of it, for all practical purposes

it consisted merely of the 11,000-man XXIII Corps, and its commander,

Major General John M. Schofield, hitherto had seen little field service.

But he was capable as well as ambitious, and during the campaign his

small corps would accomplish much.

Sherman's artillery numbered 254 cannons, his cavalry about 11,000

troopers. The former was superior to its Confederate counterpart in all

except the valor of its gun crews, having more rifled pieces and better

ammunition. The latter, on the other hand, suffered from the poor

leadership of its four division commanders, a situation made worse by

the fact that the sole central control over its operations came from

Sherman himself, and he lacked a realistic understanding of the

limitations and potentialities of the mounted arm.

Sherman's chief concern was supplying his army as it marched and

fought its way through northern Georgia. To do so he had to depend

mainly on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. When he assumed

command in March it was delivering enough supplies to maintain the

forces around Chattanooga but not enough to sustain an offensive.

Therefore, he issued orders designed to remedy this situation. By the

end of April an average of 135 freight cars a day were coming into

Chattanooga—more than the minimum required. Sherman also collected

5,000 wagons and 32,000 mules to haul what the trains delivered, giving

himself the means to operate away from the railroad whenever that proved

necessary or desirable.

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL WILLIAM J. HARDEE (LC)

|

|

BEFORE THE MARCH ON ATLANTA, SHERMAN'S ARMIES GUARDED SUPPLY LINES AT

PLACES LIKE WAUHATCHIE BRIDGE. (USAMHI)

|

To meet and, he hoped, defeat Sherman when he advanced, Johnston by

the end of April had about 55,000 troops present for duty, backed by 144

cannons. The infantry and most of the artillery were organized into two

corps, those of Lieutenant Generals William J. Hardee and John Bell

Hood, and the cavalry, which numbered approximately 8,500 and was

commanded by Major General Joseph Wheeler.

Known as "Old Reliable," Hardee was a veteran of virtually all of

the Army of Tennnessee's battles.

|

Known as "Old Reliable," Hardee was a veteran of virtually all of the

Army of Tennessee's battles. Following that army's humiliating rout at

Chattanooga, he had become its acting commander, but when President

Davis offered him the post on a regular basis he had declined it.

Hood, who was only thirty-two, had compiled a brilliant combat record

as a brigade and division commander in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia,

and at Chickamauga his de facto corps's exploitation of a gap in the

Union front produced the Confederate victory. His military success,

however, had come at a high personal cost: at Gettysburg shrapnel

paralyzed his left arm, at Chickamauga a bullet shattered his right

thigh bone, necessitating amputation near the hip. As a result, he could

not, despite an artificial leg, walk without the aid of crutches, and to

ride he had to be strapped to his horse. Even so, his fighting spirit

remained intact, and Johnston sought and welcomed his assignment to a

corps command in the Army of Tennessee, calling it "my greatest

comfort." He did not know that Hood had written Davis on April 13

deploring Johnston's failure to take the offensive: "When we are to be

in a better condition to drive the enemy from our country I am not able

to comprehend."

Wheeler had headed the Army of Tennessee's cavalry since the fall of

1862 and was energetic, aggressive, and resourceful. Unfortunately, he

also (like most Civil War cavalry leaders) was unable to exercise

effective control over units not under his personal supervision and had

a penchant for exaggerating his successes and minimizing or concealing

his failures. Nevertheless he gave Johnston's army what Sherman's

lacked—a capable, experienced commander for its horsemen, who

throughout the campaign would more than hold their own against the Union

troopers.

|

JOE BROWN'S PETS

Under the Confederate conscription laws, all able bodied males

between the ages of eighteen and forty-five were subject to military

service except an assortment of exempted classes. Among those who were

exempt were civil officials and officers in the state militia

organizations. In Georgia, so many men of military age had gained

exemption through state or county offices that they came to be called

"Joe Brown's pets," after the controversial wartime governor. Howell

Cobb, a political rival of Brown's, complained of districts that had

gone without justices of the peace for years before the war that were

served by several once hostilities began, and county courts suddenly saw

flocks of clerks and deputy sheriffs although the war had virtually

suspended all court business, These men were all fit for duty, Cobb

said, as were the 2,726 militia officers who had only themselves to

command, their enlisted members having all gone into the army.

Once Sherman invaded Georgia, Brown called out the civil servants and

militia officers, directing their formation into companies and

regiments. He ordered them to report to Atlanta, where they were

organized into two brigades of three regiments apiece and a battalion of

artillery: more than 3,000 men, altogether. Those militia officers who

were not elected for commissions in this new organization took up arms

as enlisted men.

|

GENERAL GUSTAVUS SMITH (USAMHI)

|

Major General Gustavus W. Smith took command of them in June, when

they were assigned to guard the crossings of the Chattahoochee River,

When Johnston anchored his army on Kennesaw Mountain, he ordered the

militia north of the Chattahoochee to support the cavalry on his left.

Under Smith the militia twice found itself within skirmishing distance

of Federal forces, and it was among the last troops to fall back across

the river. Johnston assigned the little division, which was now reduced

to about 2,000 muskets, to the trenches east of Atlanta, along the

Georgia Railroad.

In the Battle of Atlanta on July 22 the militia occupied works

opposite the apex of the folded Union line and advanced against the XVII

Corps when it retreated from Hardee's attack. The militia division was

not heavily engaged, however, and only lost about fifty men in that

engagement.

Early in August, as Sherman tightened the noose around Atlanta,

Governor Brown called out the "reserve militia"—men between

forty-six and fifty-five and boys aged sixteen or seventeen. Eventually

some 2,000 such reserves reached General Smith, who noted that his

division never exceeded 5,000 men. The militia suffered from a lack of

both training and equipment. The first regiments of military and civil

officers were armed from surplus army muskets, but most of the old men

and boys came with their own flintlocks, hunting rifles, and shotguns.

More than two-thirds were never issued cartridge boxes, according to

Smith.

|

THE MILITIA OCCUPIED WORKS LIKE THIS IN THE DEFENSE OF ATLANTA. (USAMHI)

|

In the final month of the siege the militia held the defenses west of

the road to Marietta, and when the army retreated from Atlanta Smith's

men acted as rear guard to Hood's reserve artillery train. The original

regiments of civil and military officers had spent about a hundred days

under arms by the time Atlanta fell, and for half that time they had

been under fire. Smith and Hood both praised the militia men for their

performance during the campaign, but straggling on the retreat caused

Smith to observe the imprudence of putting men over the age of fifty in

the field. When the army had reassembled outside the city, Smith

recommended a thirty-day furlough for his entire command, which was

granted. In October the militia reassembled to contest Sherman's March

to the Sea.

—William Marvel

|

The vast majority of the soldiers of both armies were battle-hardened

veterans. This meant that they knew how to fight—and also when it

was best not to fight. In particular, they took a dim view of charging a

fortified enemy: "It don't pay." Owing to the almost total tactical

dominance that the rifled musket gave the defense over the offense

during the Civil War, rarely did frontal assaults succeed, and when they

did the price usually was excessive, as witness Chickamauga, where the

Confederates lost one-third of their total number in what proved to be a

strategically barren victory. The reluctance of Billy Yank and Johnny

Reb at this stage of the war to attack except when the foe was thought

to be weak, or in the open, or to have an exposed flank would have a lot

to do with what happened and did not happen once the campaign for

Atlanta got under way.

|

|