|

BATTLE OF ATLANTA

The night was hot, the roads dusty, and Hardee's soldiers already

were half-exhausted from two days of fighting and marching, having spent

July 21 holding the Federals east of Atlanta in check. Soon it became

apparent that they could not hope to reach Decatur by morning. Hood

thereupon, at Hardee's request, modified his plan: Wheeler would proceed

to Decatur, where McPherson's wagon train reportedly was parked, but

Hardee would attack as soon as he got beyond McPherson's flank.

|

UNION SOLDIERS ARE PHOTOGRAPHED ON THE LINES BEFORE ATLANTA SHORTLY

BEFORE THE BATTLE ON JULY 22. (LC)

|

Sherman, when informed early on the morning of July 22 that the enemy

seemed to have withdrawn from in front of McPherson and Schofield, at

once concluded that Hood was evacuating Atlanta and so instructed

Schofield to occupy the city while the rest of the army gave pursuit.

Then, on discovering that strong Confederate forces still occupied a

line closer to Atlanta, Sherman decided that Hood intended to hold the

place after all and that therefore the time had come to execute the

strategy for taking it that he had outlined to Grant back in April: cut

its railroad connections to the Confederacy. One of these, the line

between Atlanta and Montgomery, already had been severed by a recent

raid out of Tennessee into Alabama by Major General Lovell Rousseau's

cavalry. Hence Sherman ordered McPherson to send Dodge's XVI Corps back

to the Decatur area to wreak further destruction on the Georgia Railroad

to Augusta, after which the Army of the Tennessee would swing north,

then west of Atlanta to strike the Macon & Western Railroad, the

breaking of which would completely isolate the city.

McPherson did not like this order and he went to Sherman to tell him

why: large Confederate forces had been seen moving south and he feared

an attack on his vulnerable left flank. Sherman, although he thought

McPherson's concern was unwarranted, agreed to postpone the

implementation of the order until 1 P.M. If by then the Rebels had not

attacked, they never would.

The morning passed and no attack came. At noon Sherman sent a message

to McPherson instructing him to direct Dodge to send Brigadier General

John Fuller's division of the XVI Corps to Decatur to tear up tracks but

to leave that corps other division, Sweeny's, where it was, namely to

the rear of McPherson's flank to which point it had marched during the

morning after having been posted the previous evening on the right flank

of the Army of the Tennessee to plug a gap between it and the XXIII

Corps. McPherson did as Sherman directed. But before his dispatch could

reach Dodge, an increasingly loud sound of firing came from the

southeast.

|

SPRAGUE'S BRIGADE AT DECATUR, GEORGIA. (BL)

|

It was Hardee, at long last launching his attack on the Union left

and rear. Through no fault of his, its timing could not have been more

unfavorable. Had it occurred either an hour sooner or an hour later, his

two right divisions, Bate's and Walker's, would have met no opposition

or only Sweeny's division. Instead, they encountered both Fuller and

Sweeny. And to make matters worse, Bate's troops had to struggle across

a swamp and Walker was killed by a Federal sniper before he could even

deploy his division. As a result, the Confederate attack in this sector

lacked cohesion and punch and soon was repulsed.

Likewise, Wheeler, although he took Decatur, failed to capture

McPherson's wagon train, which escaped along with most of the Federals

defending the place.

Cleburne's troops, on going into action, enjoyed better luck, for

they happened to enter a wide gap between the right of XVI Corps and the

left of the XVII Corps, which was at the south end of McPherson's line

facing Atlanta. Furthermore, as they advanced McPherson himself,

accompanied only by an orderly, came riding among them on his way to

check the XVII Corps' situation after witnessing he XVI Corps beat back

Bate's and Walker's attack. The Confederates yelled at him to surrender;

instead he tried to escape and was shot dead from his horse. As he

demonstrated on May 9 at Resaca, and two days earlier on the road to

Atlanta, he was too lacking in aggressiveness to be a first-rate combat

commander, but his caution served the Union cause well on July 22.

Pushing on, Cleburne's men struck the flank and rear of the XVII

Corps while Cheatham's Division, still under Maney, assailed its front.

These attacks, however, were uncoordinated, enabling the Federals to

repel them by scrambling from one side of their entrenchments to the

other. Not until after nearly two hours of bloody fighting did one of

Cleburne's brigades join with one of Maney's to hit the Union line

simultaneously in front and rear, causing the XVII Corps to fall back to

a bald hill which, because of its height, dominated the battlefield and

so was the key to it.

|

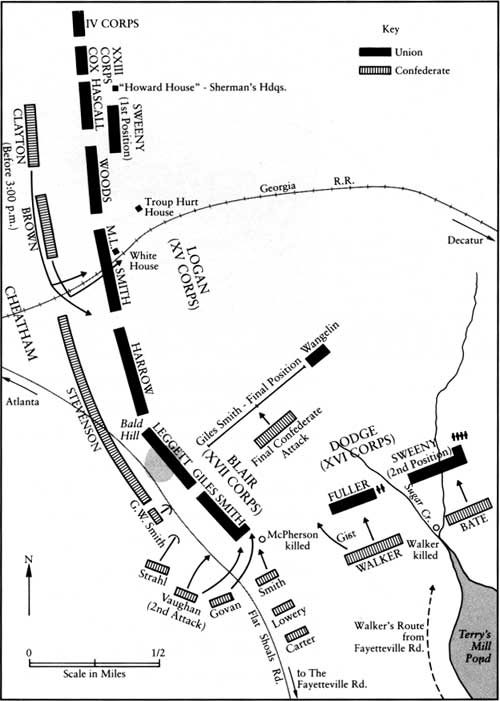

BATTLE OF THE BALD HILL, JULY 22

On the evening of July 21 Hardee's Corps, accompanied by Wheeler's

cavalry, began marching southward with the object of swinging around the

Union left flank to Decatur, where it would strike McPherson's forces,

after which it was to join Cheatham's and Stewart's Corps in sweeping

the rest of the Union army toward the Chattahoochee. When it became

evident that Hardee could not reach Decatur by morning, Hood authorized

him to attack on getting into the immediate rear of McPherson. Hardee

could not accomplish this until afternoon on July 22. His two right

divisions, Walker's and Bate's, encountered Dodge's XVI Corps, which

repulsed them. Only Cleburne's and a portion of Maney's division

succeeded in penetrating a gap between the XVI and XVII Corps, in the

process killing McPherson, and then bending back the XVII Corps until it

occupied a line facing southward that was anchored on an elevation

called the Bald Hill. Hood sought to transform this partial victory into

a complete one by having Brown's and Clayton's Divisions attack the XV

Corps. Two of Brown's brigades broke through along the Georgia Railroad.

But a counterattack by the XV Corps drove back Brown's troops and ended

the Confederate threat in this sector. Even though Hardee continued to

assail the Bald Hill until nightfall, he failed to seize it and the

battle ended in another bloody defeat for Hood.

|

Hoping to help Hardee take the hill, Hood ordered Cheatham to attack

the XV Corps, which was astride the Georgia Railroad and to the right of

the XVII Corps. Thanks to an inadequately defended railroad cut, two

brigades from Brigadier General John C. Brown's Division (formerly

Hindman's) penetrated the XV Corps' line and captured a four-gun

battery. Their success, however, was short-lived. A Union counterattack,

personally led by "Black Jack" Logan, who had assumed command of the

Army of the Tennessee on McPherson's death, drove the Confederates back

and restored the XV Corps' front. To the south, Hardee continued to

assault the bald hill with both infantry and artillery until after it

was dark, but to no avail as its defenders held on grimly. (The hill

became known as Leggett's Hill after the commander of the XVII Corps

division that defended it, Brigadier General Mortimer Leggett, who after

the war purchased it.)

|

CONFEDERATE TROOPS OVERRUN A UNION BATTERY DURING THE BATTLE OF ATLANTA.

(FROM MOUNTAIN CAMPAIGNS IN GEORGIA)

|

|

THE PERIOD PRINT DEPICTING THE BATTLE OF ATLANTA SHOWS SOMEWHAT

INACCURATELY THE DEATH OF GENERAL JAMES MCPHERSON. (LC)

|

Night ended what would be called the Battle of Atlanta, the largest

engagement of the Atlanta campaign, one that cost the Confederates about

5,500 casualties and the Federals nearly 4,000, a large proportion of

whom were prisoners from the XVII Corps. Again Hood failed in an attempt

to smash a wing of Sherman's army, a failure he attributed to Hardee for

allegedly not carrying out orders to strike the Union rear but which in

truth was caused by the semifortuitous presence of the XVI Corps in

position to protect that rear and the steady fortitude of the soldiers

of the XVII Corps. On the other hand, Sherman deserved little credit for

the Federal victory, a victory which probably would have been a defeat

had not McPherson persuaded Sherman to modify his orders regarding the

XVI Corps. Moreover, during Cheatham's attack on the XV Corps, Sherman

rejected proposals from Schofield and Howard that their corps strike

Cheatham's exposed left flank, a move that almost surely would have led

to the rout of two-thirds of Hood's army.

|

|