|

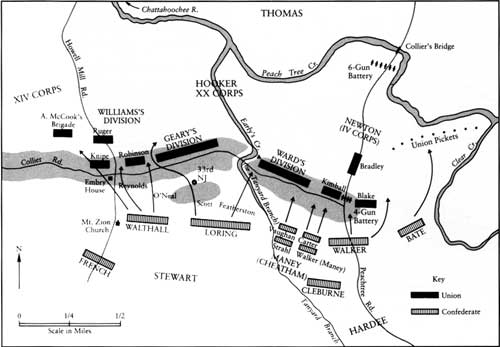

BATTLE OF PEACHTREE CREEK

In becoming commander, Hood took on the task of stopping, or better

still defeating, Sherman. How was he to do it? On July 19 his cavalry

reported that McPherson and Schofield were moving toward Decatur, six

miles east of Atlanta, and that Thomas was beginning to cross Peachtree

Creek, five miles north of the city. Thus a wide gap existed between the

two wings of the Union army. Hood at once decided to exploit it. At a

late-night conference with his top generals he outlined a plan whereby,

come tomorrow, Wheeler and Major General Benjamin F. Cheatham, who now

headed Hood's former corps, would hold McPherson and Schofield in check

while Hardee's and Stewart's Corps, under the operational command of

Hardee, attacked Thomas's forces and drove them back to the banks of the

Chattahoochee and Peachtree Creek at the point where the latter flowed

into the former, trapping and destroying them. Then the following day

the whole Confederate army would fall upon and crush McPherson and

Schofield.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

BATTLE OF PEACHTREE CREEK

Sherman's army advanced southward from the Chattahoochee in two

groups. One, consisting of McPherson's Army of the Tennessee and

Schofield's Army of the Ohio, marched to the Decatur area where it

severed the Georgia Railroad and then turned west toward Atlanta. The

other, Thomas's Army of the Cumberland (IV, XIV, and XX Corps), moved on

Atlanta directly from the north. Hood, perceiving the wide gap between

the Union forces, decided to exploit it. On the afternoon of July 20,

Hardee's and Stewart's Corps assailed Thomas south of Peachtree Creek.

Although the Confederates achieved some initial successes against the

surprised Federals, their attack failed owing to poor coordination and

inadequate strength.

|

If successful, this plan would result in the greatest victory of the

war. Unfortunately for the Confederates, it was based on the premise

that McPherson and Schofield were advancing toward Decatur when in fact

they were advancing from it and so were closer to Atlanta than Hood

thought. Consequently, late on the morning of July 20 Wheeler, whose

cavalry, fighting dismounted, opposed Mcpherson's advance along the

Decatur-Atlanta road, had to call for help from Cheatham on his left.

This caused Cheatham to shift to his right, which in turn obliged Hardee

and Stewart to slide rightward also, thereby delaying their attack,

which had been scheduled to begin at 1 P.M., by several hours.

|

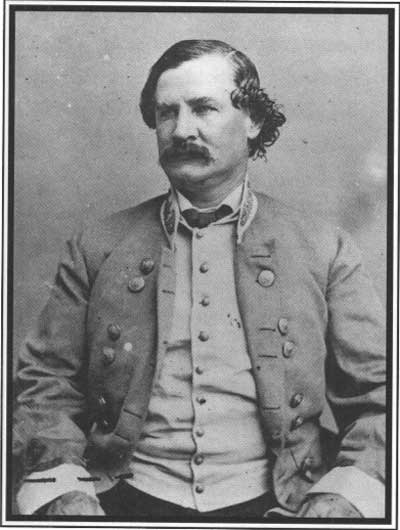

MAJOR GENERAL BENJAMIN F. CHEATHAM

|

Yet Hardee's and Stewart's redeployment actually enhanced their

prospects of success, for it placed most of Hardee's Corps beyond

Thomas's left flank, which was held by Newton's division of the IV

Corps—that corps' other two divisions were with Schofield—and

put Stewart's Corps in position to assail the mainly unentrenched XX

Corps instead of the strongly fortified XIV Corps, whose commander,

General John Palmer, did not share the prevailing Union view that there

was little or no danger of a Rebel attack north of Atlanta. In short,

luck was with the Confederates; now all they needed was skill and

determination.

Both of these qualities were conspicuous for their absence in

Hardee's assault. Bate's Division on the right literally got lost in the

Peachtree Creek bottomlands and thus did not engage the enemy, at least

not seriously. In the center Major General W. H. T. Walker's Division

delivered a series of disjointed charges that Newton's troops, fighting

from behind hastily improvised breastworks, easily repelled. And on

Hardee's left Cheatham's Division, headed by Brigadier General George

Maney, either did not attack at all or else went to ground on beholding

Yankee trenches. With about 15,000 available troops, Hardee failed to

dislodge, much less overpower, Newton's 3,200 men.

|

ON-THE-SCENE SKETCH BY THEODORE H. DAVIS SHOWS GENERAL HOOKER'S POSITION

DURING THE BATTLE OP PEACHTREE CREEK ON JULY 20. (COURTESY OF AMERICAN

HERITAGE PRINT COLLECTION)

|

Stewart's attack, in contrast, was everything that Hardee's was not.

Delivered with great ferocity by Loring's and Major General Edward

Walthall's Divisions—Stewart had to hold back Major General Samuel

French's Division and two brigades to cover his left flank—it

nearly broke through the XX Corps, which was caught off guard and for

the most part undeployed and unfortified. Loring's and Walthall's four

brigades, however, simply lacked the strength to sustain their advances

against Hooker's nine brigades, which quickly rallied, and so they had

to retreat. Undaunted, Stewart called on Hardee to renew the attack.

Hardee concurred and ordered forward Cleburne's Division, hitherto held

in reserve. But before Cleburne's crack troops could charge, Hardee

received word from Hood that Wheeler urgently needed assistance,

whereupon he canceled their assault and sent them to the east side of

Atlanta. So ended the Battle of Peachtree Creek. In it Hood, who lost at

least 2,500 men, was foiled in his attempt to smash one-half of

Sherman's army as a prelude to doing the same to the other half. Yet

Sherman deserved no credit for the Union victory, which cost nearly

2,000 casualties, most of them in the XX Corps. Because he was east of

Atlanta, where he expected Hood to make a stand if he made one at all,

he did not even know the battle had taken place until he received at

midnight, six hours after it ended, a message from Thomas informing him

of it. Moreover, during the height of the fighting along Peachtree Creek

he sent an order to Thomas to occupy Atlanta, as there was no strong

enemy force to oppose him. Finally, he did nothing to push forward

McPherson, who, instead of sweeping aside Wheeler's cavalry with his

25,000 infantry, advanced with such cautious slowness on Atlanta that

nightfall found him still more than a mile from the city. It was a case

of Snake Creek Gap and Resaca all over again, and again Sherman must

share the responsibility with McPherson.

|

THIS PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN AFTER THE BATTLE OF PEACHTREE CREEK SHOWS THE

GRAVES OF SOME WHO PERISHED THERE. (USAMHI)

|

The failure to drive Thomas into the Chattahoochee disappointed but

did not discourage Hood: Sherman's army remained divided and hence

vulnerable. Learning that McPherson's left flank was

exposed—Sherman had sent off the cavalry that should have been

screening it to raid the railroad between Atlanta and Augusta,

Georgia—Hood on the night of July 21 sent Hardee's Corps and

Wheeler's cavalry swinging around that flank with orders to march to

Decatur, then in the morning to pounce on McPherson from the rear,

routing his forces and opening the way for Cheatham's troops to join

with Hardee's and Wheeler's in doing the same to the rest of the Union

army east of Atlanta. Meanwhile, Stewart. whose corps had fallen back to

the city's north-side fortifications, would hold Thomas in check.

|

|