|

SIEGE AND RAIDS (AUGUST 1-25)

Three times Hood had tried to strike a knockout blow against

Sherman's army or at least cripple it so badly that it would have to

retreat. Each time he had failed, in the process losing more men

(11,000) than he could afford and intensifying the already strong

reluctance of his remaining troops to charge an entrenched foe.

Nevertheless, he stopped Sherman from taking Atlanta and, for the time

being, achieved the same sort of stalemate that Lee maintained at

Richmond, where on July 30 his forces inflicted yet another bloody

defeat on Grant in the Battle of the Crater. If Hood could manage to

hold on to Atlanta until the fall elections in the North, there was an

excellent chance that the Northern public, despairing of victory, would

repudiate Lincoln and his policy of Union through war and turn to the

Democrats with their promise of Union through peace. As July gave way to

August, the Democrats confidently predicted such an outcome and many

Republicans feared that they were right.

Fully aware that unless he won on the battlefront the war might be

lost on the home front, Sherman spent the first three weeks of August

trying to get Hood out of Atlanta and himself into it by some means

other than assaulting its fortifications, which would have been suicidal

given their enormous strength, or by undertaking another large-scale

flanking maneuver, something he was reluctant to do as it would mean

again leaving his railroad supply line, this time while deep in enemy

territory.

|

STONEMAN'S RAID

By the last week of July 1864, Union forces had closed off three of

the four railroads leading into Atlanta. Hood's army subsisted entirely

on supplies coming in from the south, along the line of the Macon &

Western Railroad.

With his army stretching in a wide crescent around the city, Sherman

decided to snip this final corridor by sending out strong forces of

cavalry from either tip of that crescent. The two would converge on the

railroad at Lovejoy's Station, ripping up both the tracks and telegraph

lines for several miles. To lead the raid from his left, Sherman chose

Major General George Stoneman, who was to take three small brigades of

his own, numbering about 2,000 men, and a division of 3,000 more under

Brigadier General Kenner Garrard. Garrard's troops had just returned

from a raid to Covington, and Sherman cautioned Stoneman against taxing

Garrard's worn-out horses. From his right, Sherman sent Brigadier

General Edward McCook with his two-brigade division and a provisional

division under Colonel Thomas Harrison. This wing totaled about 4,000

troopers, but Harrison's half of that force had just arrived from

Alabama after an exhausting raid, and McCook was warned to use those

troops only as a reserve. These assignments left Sherman with only one

division of cavalry in his entire army.

|

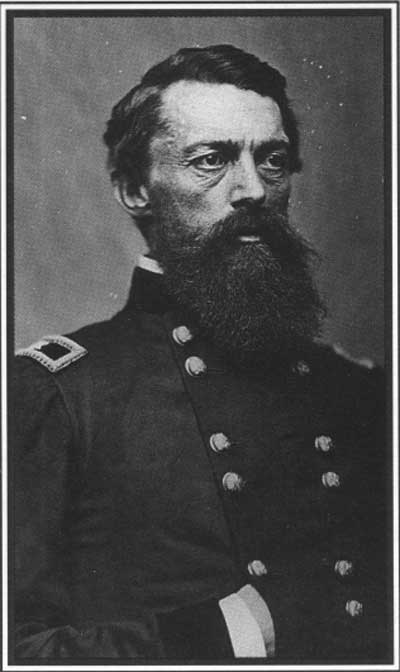

GENERAL GEORGE STONEMAN (LC)

|

Stoneman asked at the last moment for permission to attack Macon,

releasing hundreds of imprisoned Union officers there, and to venture on

to Andersonville from there, to free more than 30,000 men in that

prison. Sherman granted him leave to try, but only after destroying both

the railroad and the Confederate cavalry under Major General Joseph

Wheeler.

Stoneman's hunger for the fame of liberating Andersonville led him to

ignore both his orders and good judgment. His column left Decatur before

dawn on July 27, and when he encountered Southern cavalry he left

Garrard's division to contend with it. Wheeler drove Garrard back the

next morning, leaving one brigade to monitor him while he sent the

majority of his command after Stoneman, who had struck south for Macon.

Meanwhile, Wheeler detached further troops to confront McCook's

incursion, many miles to the west, where Brigadier General William

Jackson stood alone with one intact brigade of horsemen.

McCook ripped up more than two miles of the Macon & Western rail

lines, tore down several miles of telegraph wire, and pounced upon

Confederate supply trains, burning hundreds of wagons full of

provisions, killing the mules that pulled them, and capturing over 400

prisoners. Stoneman did not arrive to join him, so instead of finding

reinforcements McCook found Wheeler's cavalry, which struck the rear of

his command. McCook tried to escape by sweeping west, toward Newnan, but

near there he was stopped by another of Wheeler's detached brigades.

Wheeler soon hit McCook from behind again with another brigade, and the

outnumbered Confederates convinced the Federals that they were

hopelessly surrounded. McCook ordered the commanders of his own two

brigades to release their captives and break out individually, while he

held the enemy off with Harrison's division; eventually McCook cut his

own way out, too, and the fragments of his command fled piecemeal toward

the Chattahoochee, leaving behind hundreds of their comrades as

prisoners, including both of McCook's brigade commanders and Colonel

Harrison. The survivors started dribbling into Marietta on August 2, too

exhausted for immediate service.

Stoneman reached Macon July 30, but found it defended at the Ocmulgee

River by an inexperienced collection of Georgia Reserves, militia, and a

number of citizen companies. He prodded at the town from the left bank

of the Ocmulgee but failed to force a crossing. Stoneman turned his

division to the south with the intention of riding to Florida, but

reports of Southern cavalry threatening the river crossing in that

direction convinced him to turn back to the north, for his starting

place. On the morning of July 31, at Sunshine Church, he ran head-on

into the three brigades Wheeler had sent after him. Like McCook, he

supposed himself outnumbered, and also like McCook he ordered two of his

brigadiers to break away while he remained with the third to cover their

escape.

Stoneman and more than 700 of his men surrendered that afternoon, and

within a day or two they occupied the very prisons they had intended to

liberate.

Instead of closing off Hood's supply line, forcing the evacuation of

Atlanta, and freeing tens of thousands of prisoners, Stoneman's raid had

resulted in the virtual elimination of two Union cavalry divisions.

—William Marvel

|

First he made a second attempt to reach and block the Macon railroad

by extending his right beyond the Confederate left. For this purpose he

instructed Schofield to take command of Palmer's XIV Corps and with it

and his own XXIII Corps advance south beyond the Lick Skillet road,

where the Army of the Tennessee remained on the defensive. Putting

Schofield over Palmer, however, invited trouble. Palmer, a political

general who despised West Pointers, was tired of war, and wanted to go

home, flatly refused to take orders from Schofield, declaring (quite

correctly) that he was senior to him in rank. As a consequence,

Schofield could employ only the XXIII Corps, and an assault by one of

its brigades on August 6 against what he hoped would be a vulnerable

point in the Confederate line along Utoy Creek was parried by Bate's

Division. Meanwhile, Palmer, who had offered to do so several times

previously during the campaign, resigned as commander of the XIV Corps,

to be replaced by Jefferson C. Davis, a competent general but one whose

main claim to fame was (and remains) the murdering of a fellow Federal

general in Louisville in 1862.

|

THE CONFEDERATES HAD SURROUNDED ATLANTA WITH FORTS AND BARRICADES TO

PROTECT IT FROM UNION ATTACK. SHOWN HERE IS ONE OF THE REBEL WORKS IN

FEDERAL POSSESSION. (LC)

|

|

FORTIFIED LINES GUARD ATLANTA. (LC)

|

Next Sherman endeavored, as he put it in a telegram to Halleck, to

"make the inside of Atlanta too hot to be endured." Starting on August 9

his artillery rained shells and solid shot on the city both day and

night. The bombardment did considerable damage to buildings in the

northern part, killed and injured a hundred or so civilians, among them

women and children, but achieved no military effect whatsoever. Indeed,

soon the townspeople, many of whom constructed dugouts in their

backyards, came to regard the Yankee barrages as more a nuisance than a

serious danger.

Sherman, who even as he ordered the bombardment admitted that "I am

too impatient for a siege," thereupon decided that he had to make

another big flanking move after all. But before this could get under

way, Wheeler with five to six thousand of his best cavalry descended

upon the Western & Atlantic Railroad north of the Chattahoochee,

sent there by Hood in an effort to force Sherman to retreat by

destroying his supply line. For several days during mid-August Sherman

issued a stream of orders designed to counter Wheeler's raid while

awaiting reliable word as to its outcome. When that word came, he felt

most relieved: although Wheeler captured a small garrison and tore up

some track near Dalton and a few other places, he did no damage to the

railroad that could not be (and was) rapidly repaired. Better still,

from Sherman's standpoint, he continued northward into East Tennessee,

in effect taking his cavalry out of the campaign.

Realizing this, Sherman made another attempt to break Hood's supply

line with his own cavalry (what was left of it). On his orders Brigadier

General Judson Kilpatrick with 4,700 troopers struck the Macon railroad

at Jonesboro, fifteen miles due south of Atlanta, on the evening of

August 19, then on the following day endeavored to do the same at

Lovejoy's Station, only to be repulsed by two brigades of Jackson's

cavalry supported by infantry. Returning to Union lines on August 22,

Kilpatrick boasted to Sherman that it would take the enemy ten days to

repair the damage he had inflicted on the railroad.

|

SHERMAN AT THE SIEGE OF ATLANTA PAINTING BY THUR DE THULSTRUP.

(COURTESY OP THE SEVENTH REGIMENT FUND, INC.)

|

|

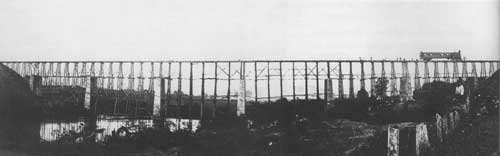

THE REBUILT RAILROAD BRIDGE SPANS THE CHATTAHOOCHEE. (U.S. MILITARY

ACADEMY LIBRARY, WEST POINT. NY)

|

From Sherman down to the drummer boys, the Federals felt that the

final, decisive act of the campaign had begun.

|

Sherman doubted this and with good reason, for already trains were

entering Atlanta, trains that could only be coming from Macon. Hence on

the night of August 22 he telegraphed Halleck that although he had hoped

that Kilpatrick's raid would spare him the need to make "a long,

hazardous flank march," he would have to "swing across" the Macon

railroad "in force to make the matter certain."

During the nights of August 25 and 26 the Union army pulled out of

its trenches and began marching in a great arc to the west and south of

Atlanta, leaving behind only the XX Corps to guard the rebuilt railroad

bridge over the Chattahoochee. From Sherman down to the drummer boys,

the Federals felt that the final, decisive act of the campaign had

begun.

|

|