|

POST-MORTEM

On August 23, the day after Sherman definitely decided to swing the

bulk of his army to the south of Atlanta, Lincoln had the members of his

cabinet sign, unseen, a memorandum stating that "it seems exceedingly

probable that this Administration will not be reelected. Then it will be

my duty to so cooperate with the President-elect, as to save the Union

between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his

election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterward."

On August 31, even as Sherman's army repulsed Hardee's attack at

Jonesboro and reached the Macon railroad, the Democratic national

convention, meeting in Chicago, nominated General George B. McClellan

for president on a platform that declared the war a failure and called

for "a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention

of the States or other peaceable means, to the end that at the earliest

practicable moment peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal

Union of the States."

|

UNION SOLDIERS PHOTOGRAPHED IN A FORT NEAR ATLANTA. (LC)

|

Thus as August drew to an end both Lincoln and the Democrats expected

that a war-weary North, despairing of victory, would elect a president

committed to restoring the Union by means of peace rather than force.

And the same expectation prevailed in the South, where on August 20 the

Richmond Sentinel, which reflected the views of Jefferson Davis,

predicted that if the Confederate armies continued to hold Grant and

Sherman at bay for just six more weeks, "we are almost sure to be in

much better condition to treat for peace than we are now" for the North

no longer would be willing and therefore able to go on with the war.

Sherman's capture of Atlanta immediately and decisively reversed the

mood of the North and the expectations of Lincoln, the Democrats, and

the South. To the majority of Northerners it meant that the war was

being won and so should be continued until the Union was restored and

slavery, the thing that had caused the war, was totally eradicated.

Likewise, Lincoln's pessimism about his election prospects, which other

Republican leaders shared, turned to optimism, an optimism that proved

fully justified when he was reelected by a landslide majority. On the

other hand, the fall of Atlanta wrecked both the Democratic platform and

McClellan's candidacy. And in the South it became clear to all except

the most fanatical that the North would go on with the war until its

superior might prevailed, as it did, even though the dwindling remnants

of the Confederate army struggled on desperately for six more months

before Lee mounted the steps of the McLean house at Appomattox Court

House.

|

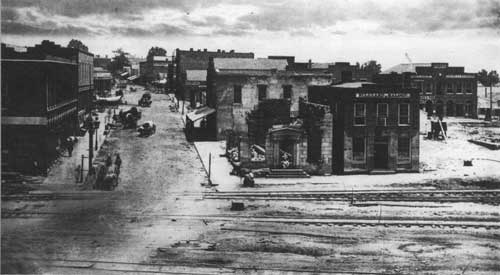

SHERMAN ORDERED HIS MEN TO DESTROY PUBLIC BUILDINGS LIKE THIS BANK. BUT

NOT PRIVATE DWELLINGS OR ENTERPRISES. (LC)

|

|

SHERMAN'S MEN MUTILATE THE RAIL LINES IN ATLANTA. (LC)

|

Johnston blamed Davis and Hood for the loss of Atlanta and they in

turn blamed Johnston. Actually all three of them shared the

responsibility. Davis badly overestimated the military potential of the

Army of Tennessee and underestimated the power of the Federal forces

arrayed against it. Yet he furnished Johnston with more troops than Lee

had to oppose Grant (about 75,000, whereas Lee had about 60,000); he

retained Johnston in command until it became manifest that he could not

be relied on to make a whole-hearted effort to defend Atlanta, the sole

thing Davis asked of him; and he was justified in not sacrificing

Mississippi and Alabama by sending Forrest to attack Sherman's supply

line, for not only would this have deprived the Army of Tennessee of its

logistical base, it also probably would not have achieved any decisive

result: not once during the Civil War did cavalry raids on railroads

turn back the advance of a major army and it is extremely doubtful that

Forrest, military genius that he was, could have provided an

exception.

Johnston, as he was throughout his Civil War career, was more

concerned during the Atlanta campaign with avoiding defeat than gaining

victory. For this reason, and because of his inferior numbers, he for

the most part adhered strictly to the defensive. Later he claimed that

by so doing he preserved the strength of his forces while wearing down

that of Sherman's to a point where he could and would have, when the

Federals neared Atlanta, carried out a successful offensive had he not

been removed from command. In truth, however, the Confederate army

during May, June, and early July suffered a higher percentage of loss

from all causes (killed, wounded, sick, captured, and desertion) than

did the Union army, with the result that Sherman was proportionately

stronger when he crossed the Chattahoochee than he was when he advanced

from the Etowah. Furthermore Johnston's postwar assertions that he could

have, had he remained in command, held Atlanta "forever" or

"indefinitely" (whatever that means) are more than dubious, they are

fatuous. If Johnston could not effectively counter Sherman's flanking

maneuvers in the mountains of northern Georgia, what good reason is

there for believing he would have done so in the relatively flat terrain

around Atlanta? None. The most likely outcome of Johnston having

remained in command is that Sherman would have entered Atlanta in late

July instead of early September.

|

THE CYCLORAMA

The hour of 4:30 on the afternoon of Friday, July 22, 1864, is

forever preserved on the half-acre canvas of the Atlanta Cyclorama at

Grant Park, on Boulevard in southeastern Atlanta. Even more impressive

than the better-known Gettysburg Cyclorama, which depicts the acme of

Pickett's Charge, this magnificent rendering of the Battle of Atlanta

stands fifty feet tall inside a marble pantheon not far from the actual

scenes portrayed.

The painting was begun in Milwaukee two decades after the battle and

was the collective creation of ten German artists who labored for a year

and a half to include every possible detail of the action. The

best-recognized feature of the painting is the brick, hip-roofed Troup

Hurt house, an unfinished structure standing near the Georgia

Railroad—a little nearer in the painting than it was actually

situated, in fact. Around the house swarm Alabama and South Carolina

troops belonging to the brigade of Brigadier General Arthur Manigault,

engaged with Midwesterners (mostly from Illinois and Ohio) under

Brigadier General Joseph Lightburn. To the right of this, the

Mississippians of Colonel Jacob Sharp's brigade can be seen moving

against the newly arrived brigade of Colonel Augustus Mersy, whose men

also hailed from Illinois and Ohio. Over the carnage soars an eagle,

said to represent "Old Abe," the mascot of the 8th Wisconsin Volunteers,

which took flight whenever its regiment went into action; if that is the

intention, the bird represents a flaw in the painting's accuracy, for

Old Abe and the 8th Wisconsin were hundreds of miles to the west, in

Mississippi, during the Battle of Atlanta.

|

A SMALL PORTION OF THE CYCLORAMA. (NPS)

|

Lightburn's Federals fell back in disorder when Manigault's and

Sharp's Confederates pierced their line: the Southerners poured through,

overrunning two Illinois batteries and rolling up the Union trenches.

They threatened to force the Federal XV Corps backward onto the rear of

the XVI and XVII Corps, which were already under attack from the front

by William Hardee's corps, but General Sherman ordered up additional

artillery and John Logan shifted Mersy's fresh brigade from the Union

left to help patch the breach. With rallied troops of Lightburn's,

Mersy's brigade swept forward to regain their lost works. It is at this

juncture that the action of the cyclorama is frozen. Battery horses lie

dead or dying between the lines, killed so the Confederates could not

carry away the artillery pieces they had overrun; Southern sharpshooters

have taken refuge in the brick house; a cleated tree that served as an

impromptu Union signal tower stands abandoned; an ambulance carries away

the grievously wounded Union general, Manning Force, who survived a

hideous wound to the upper part of his face; soldiers fight hand-to-hand

for the entrenchments.

Originally housed under a dome on Edgewood Avenue more than a century

ago, the cyclorama was later moved to Grant Park, where it was

extensively renovated in the early 1980s.

>—William Marvel

|

Hood attempted to do what Davis wanted done: shatter Sherman's army

or at least damage it so badly that it would be compelled to retreat.

Obviously he failed. Although excellent in concept, his battle plans

were unrealistic in practice, for they required too few troops to do too

much without a sufficient margin for time and error. Consequently, it

might have been better if Hood, while fighting aggressively, had sought

less ambitious objectives that were more suited to the limited offensive

capability of his army, with the purpose of throwing Sherman off

balance, putting him on the defensive, and thus denying him Atlanta as

long as possible—mayhap until after the North's presidential

election. But Hood could not have done this and still be Hood; he would

have had to been Lee. And that he was not, even though he tried his best

to be.

|

AMID THE RUBBLE OF THE ROUNDHOUSE SIT UNSCATHED LOCOMOTIVES AND FREIGHT

CARS. (LC)

|

|

SHERMAN (LEANING ON CANNON AT RIGHT) AND STAFF PHOTOGRAPHED AFTER THE

CAPTURE OF ATLANTA. (LC)

|

On the Union side the campaign for Atlanta was, as Grant declared in

a telegram of congratulations to Sherman, "the most gigantic undertaking

given to any general in the war." Sherman owed his success mainly to

Confederate mistakes, to not making any irreparable blunders of his own,

and above all to the superior power and high quality of his army, which

he maintained by not, like Grant in Virginia, repeatedly engaging in

bloody offensive battles designed to knock out the enemy with one mighty

blow but instead employing flanking moves to compel the Confederates to

abandon one strong position after another and finally Atlanta itself.

His sole major failure, one stemming from his concept of warfare and a

fixation with capturing Atlanta to the near exclusion of all other

objectives, was not to take advantage of the numerous opportunities he

had to destroy the opposing army in Georgia or mangle it so badly as to

render it strategically impotent. As a consequence, Hood's forces,

although badly battered, remained a source of danger and trouble until

Thomas finally smashed them at the Battle of Nashville in December

1864.

But if Sherman failed to do as much as he could and should have done,

he accomplished what he set out to do and had to do: take Atlanta. And

in doing that he guaranteed the North's victory by depriving the South

of its last chance of winning—of winning by not losing.

On January 1, 1864, Mary Chesnut of South Carolina had written in her

diary: "God help my country!" Nine months later, on learning of

Atlanta's fall, she wrote: "No hope." Those two words said it all.

|

Back cover: Federal Attack on Kennesaw Mountain, by Thure de

Thulstrup. Courtesy of The Seventh Regiment Fund, Inc.

|

|

|