|

KENNESAW MOUNTAIN (JUNE 7-JULY 2)

Sherman spent four days at Acworth waiting for the railroad bridge

over the Etowah to be rebuilt. On June 10, that task having been

accomplished, he began advancing along the line of the Western &

Atlantic. With him, just arrived, was the XVII Corps of the Army of the

Tennessee. Commanded by Major General Francis P. Blair, Jr., its two

divisions of 9,000 veterans more than made good Sherman's battle losses

of the past month.

Late on the morning of June 10 the Union vanguard reached Big Shanty

(present-day Kennesaw) and found itself confronted by a ten-mile-long

Confederate defense line that stretched from Brush Mountain on the east

through Pine Mountain in the center to Gilgal Church on the west.

Sherman, who had promised Major General Henry W. Halleck, the Union

army's chief of staff in Washington, that "I will not run head on

[against] his [the enemy's] fortifications," deployed his forces

parallel to this line and instructed Thomas to have the IV and XIV Corps

work their way around Pine Mountain, a move he believed would compel

Johnston to retreat because that elevation constituted a vulnerable

salient in the Confederate front.

|

PINE MOUNTAIN PHOTOGRAPHED AFTER THE BATTLE. (LC)

|

By June 14, despite incessant rains that turned the fields and roads

into quagmires, the IV Corps was close to achieving this objective.

While observing its operations Sherman noticed some Confederates atop

Pine Mountain (actually a hill only about 300 feet high) who were making

no attempt to conceal themselves. "How saucy they are!" he exclaimed,

then told Howard to have a battery fire at them. Howard passed on the

order to Captain Peter Simonson, whose cannons had checked Stevenson's

Division during the first day of fighting at Resaca exactly one month

before.

Unknown and unknowable to Sherman, among the "saucy" Confederates

were Johnston, Hardee, and Polk, discussing whether or not to evacuate

Pine Mountain. The first shot from Simonson's battery caused them to

scatter, the second (probably) struck Polk in the left side and ripped

through his chest, eviscerating him. (Three days later a Confederate

sniper killed Simonson). The Episcopal bishop of Louisiana as well as a

general—he often was referred to as the "Bishop General"—Polk

had in the pockets of his uniform coat The Book of Common Prayer

and four copies of a newly published tract entitled Balm for the

Weary and Wounded, three copies of which were inscribed to Johnston,

Hardee, and Hood. Major General William Loring assumed acting command of

Polk's Corps.

|

THE BATTLE OF KENNESAW MOUNTAIN AS SKETCHED BY A. R. WAUD. (LC)

|

During the night the Confederates withdrew from Pine Mountain. On

learning of this in the morning, Sherman jumped to the conclusion that

Johnston was retreating all along his front and so ordered his forces to

pursue, hoping to catch the enemy in the open. Once more he was

overoptimistic. Johnston did fall back, but from one strong position to

another, until on June 19 he reached the strongest one of all: Kennesaw

Mountain. This was (is) a long ridge (two miles) slanting to the

southwest and consisting of three knobs: Big Kennesaw at the northeast

end, Little Kennesaw in the middle, and a spur today called Pigeon Hill

at the lower end. Loring's troops occupied Big and Little Kennesaw,

Hardee's covered the southern extension, and Hood's Corps and Wheeler's

cavalry guarded the area to the east of the mountain and nearby

Marietta.

Sherman reacted to Johnston's new defense line by deploying the Army

of the Tennessee opposite Hood and the Army of the Cumberland facing

Loring and Hardee. At the same time he sent Schofield with his XXIII

Corps down the Sandtown road with instructions to try to find a point

where Johnston's left flank could be turned. This move caused Johnston,

on the night of June 21, to counter it by switching Hood's Corps from

the right to the left and extending Loring's front eastward so as to

cover the area vacated by Hood.

During the morning of June 22 Hooker's corps, on orders from Sherman

relayed by Thomas, shifted southward to Kolb's Farm on the Powder

Springs road, where it linked up with Schofield's forces on its right.

Hood, evidently unaware of Schofield's presence, thought he saw an

opportunity to overpower Hooker and then roll up the entire Union right

flank. Hence, without notifying Johnston, he attacked with Stevenson's

and Hindman's Divisions along and to the north of the Powder Springs

road.

|

THEODORE R. DAVIS SKETCH OF SHERMAN AND THOMAS A KENNESAW MOUNTAIN.

(COURTESY OF AMERICAN HERITAGE PRINT COLLECTION)

|

|

FEDERAL ATTACK ON KENNESAW MOUNTAIN BY THURE DE THULSTRUP. (COURTESY OF

THE SEVENTH REGIMENT FUND, INC.)

|

Fiasco, not victory, awarded Hood's impulsive initiative. Stevenson's

troops encountered such heavy fire from Williams's division and a

brigade of Cox's division that they either broke or went to ground, and

Geary's cannons alone sufficed to stop, then turn back, Hindman's

assault. Altogether the Confederates suffered about 1,500 casualties

whereas the Federals lost no more than 250 men. Understandably, Hood did

not so much as mention the Battle (if such it can be called) of Kolb's

Farm in his memoirs.

But if Hood failed in his attempt to smash Sherman's right, the

presence of his corps south of Kennesaw frustrated Sherman's attempt to

get around Johnston's left, And Sherman already was feeling very

frustrated. A month now had passed since he crossed the Etowah expecting

to reach and perhaps pass over the Chattahoochee in a few days. Yet he

still had not achieved that goal and there seemed to be no immediate

prospect that he would. Instead he was becoming, so he feared, bogged

down in a stalemate—a stalemate that might enable Johnston to do

the one thing above all he must not be allowed to do, transfer troops to

Virginia to aid Lee against Grant.

So it was that Sherman, declaring that "flanking is played out," on

June 25 ordered Thomas and McPherson to "break through" Johnston's line

with frontal assaults. Although both generals doubted that the attacks

could succeed, both dutifully proceeded to carry them out. On the

morning of June 27, following a furious but ineffective artillery

bombardment, Brigadier General Morgan L. Smith's division of the XV

Corps, which by now had been shifted to the west of Kennesaw, assailed

the Confederate positions around Pigeon Hill while further to the south

Brigadier General John C. Newton's division of the IV Corps and

Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis's division of the XIV Corps did the

same against what had become Johnston's center (see map). Smith's and

Newton's troops, despite a determined effort, failed even to reach the

Rebel works, and although a few of Davis's men, thanks to favorable

terrain, managed to scale the enemy ramparts on what henceforth would be

known as Cheatham's Hill (named after the commander of the Confederate

troops who held the hill, Major General Benjamin F. Cheatham), they

either were killed or captured and their surviving comrades forced to

take cover just below the crest of the hill. It was all over in less

than an hour, during which the Federals suffered nearly 3,000 casualties

whereas the Confederate loss came to no more than 700 men, most of them

pickets overrun in the initial Union rush. Such were the results of

Sherman doing what he had told Halleck he would not do—"run head

on" against fortifications.

|

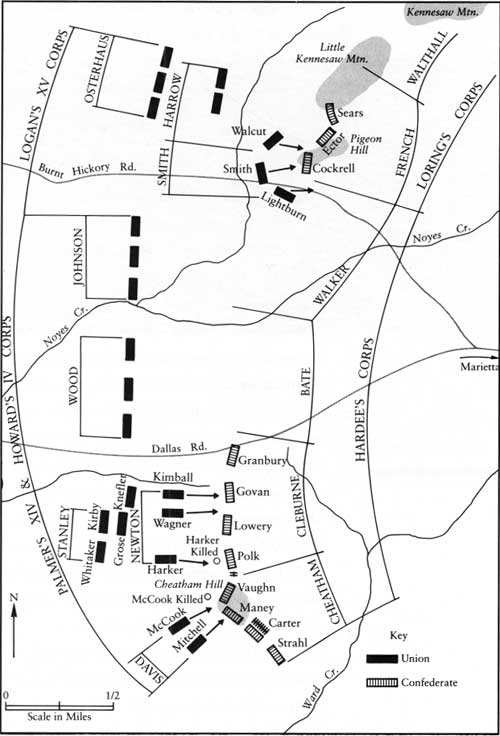

BATTLE OF KENNESAW MOUNTAIN, JUNE 27

On June 10 Sherman, his army having been reinforced by Blair's XVII

Corps, launched a new offensive designed to drive Johnston back to and

across the Chattahoochee. The Confederates fell back slowly until they

reached Kennesaw Mountain, an immensely strong position that they made

stronger still with fortifications. Here they not only halted Sherman's

advance but frustrated his efforts to outflank them. Fearing a stalemate

that might enable Johnston to reinforce Lee against Grant in Virginia,

Sherman decided to try to break through the enemy defenses with a

frontal attack. On the morning of June 27 a division of the XV Corps

assailed Johnston's right at Pigeon Hill and a division each from the IV

and XIV Corps did the same against his center. Both assaults failed with

heavy losses. Meanwhile, however, Cox's division of Schofield's XXIII

Corps worked its way to a point south of Kennesaw where it would be

possible to turn the Confederate left flank. On learning this, Sherman

transferred McPherson's Army of the Tennessee from his left to the

right, thereby compelling Johnston to retreat on the night of July

2.

|

Sherman's first reaction to the repulse, which he attributed to his

troops attacking with insufficient "vigor," was to ask Thomas, "Can you

break any part of the enemy line today?" Politely but firmly Thomas

answered in the negative. The only way, he added, that the Confederate

works could be taken would be by a regular siege-style operation.

Sherman, as Thomas doubtlessly expected, rejected this approach for it

would prolong the stalemate indefinitely.

Thus Sherman found himself left with only one

alternative—another flanking maneuver. But where? The answer came

late that afternoon in a message from Schofield: Cox's division, working

its way southward, had reached a point where it appeared that the

Confederate line terminated. After requesting and receiving confirmation

of this intelligence from Schofield, Sherman asked Thomas if he was

willing to risk a large-scale attempt to turn Johnston's left. Thomas's

reply was both prompt and blunt: "I think it decidedly better than

butting against breastworks twelve feet thick and strongly abatized."

("Abatized" referred to abatis—sharpened stakes affixed in a

crisscross fashion to logs which served the same defensive function as

modern-day barbed wire.)

|

DURING A TRUCE IN THE FIGHTING,

CONFEDERATES OF THE 1ST AND 15TH ARKANSAS OBSERVE FEDERAL TROOPS

HELPING THEIR WOUNDED FROM THE BATTLEFIELD. (FROM MOUNTAIN

CAMPAIGNS IN GEORGIA)

|

Because Schofield's corps was too small and Thomas's forces already

stretched to their safe limit, Sherman also had no choice except to

employ McPherson's three corps for the turning movement, even though

that would mean abandoning a direct connection with the railroad.

(Ironically, when Thomas on June 23 proposed taking advantage of Hood's

shift to the Confederates' left by having McPherson swing around their

right, Sherman refused on the grounds that it would expose the railroad

and his forward supply bases to enemy seizure. Had such a move been

made, almost surely it would have led to Johnston's immediate retreat,

as only a thin screen of infantry and Wheeler's cavalry guarded Kennesaw

and Marietta from a Union thrust from the east).

At long last the way was open for Sherman's men to "swarm" along

the Chattahoochee.

|

Early on the morning of July 2 Morgan Smith's division of the XV

Corps left its trenches west of Pigeon Hill and headed down the Sandtown

road, to be followed during the night by the rest of the XV Corps and

the XVI and XVII Corps. That same night Johnston, who long had

anticipated precisely this movement and saw no way of countering it,

evacuated his lines on and around Kennesaw and retreated southward

through Marietta. At long last the way was open for Sherman's men to

"swarm" along the Chattahoochee.

|

|