|

Hot Springs National Park Arkansas |

|

NPS photo | |

Water. That's what attracts people to Hot Springs. Old documents show that American Indians knew about and bathed in the hot springs during the late 1700s and early 1800s. Their ancestors may have also known about the hot springs. Some believe that the traces of minerals and an average temperature of 143°F/62°C give the waters whatever therapeutic properties they may have. People also drink the waters from the cold springs, which have different chemical components and properties. Besides determining the chemical composition and origins of the waters, scientists have determined that the waters emerging from these hot springs are over 4,000 years old. The park collects 700,000 gallons a day for use in the public drinking fountains and bathhouses.

French trappers, hunters, and traders became familiar with this region during the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1803 the United States acquired the area when it purchased the Louisiana Territory from France. The next year President Thomas Jefferson dispatched an expedition led by William Dunbar and George Hunter to explore the newly acquired springs. Their report to the president was widely publicized and stirred up interest in the Hot Springs of the Washita.

In the years that followed, more and more people came here to soak in the waters. Soon the idea of "reserving" the springs for the nation took root, and territorial representative Ambrose H. Sevier sent a proposal to Congress. Then in 1832 the federal government took the unprecedented step of setting aside four sections of land here. It was the first U.S. reservation created to protect a natural resource. Boundaries were not marked, and by the mid-1800s individuals had filed claims and counterclaims on the springs and surrounding land.

The Early Years The first bathhouses were crude canvas and lumber structures, little more than tents perched over individual springs or reservoirs carved out of the rock. Later, businessmen built wooden structures, but they frequently burned, collapsed because of shoddy construction, or rotted due to continued exposure to water and steam. Hot Springs Creek, which ran right through the middle of all this activity, drained its own watershed and collected the runoff of the springs. Generally it was an eyesore—dangerous at times of high water and a mere collection of stagnant pools in dry times. In 1884 the federal government put the creek into a channel, roofed it over, and laid a road above it. Much of it runs beneath Central Avenue today.

Seeking Health and Luxury The government took active control of the springs and reservation for the first time after all the private claims on reservation land were settled in 1877. It approved blueprints for private bathhouses ranging from simple to luxurious. The government even operated a free bathhouse and public health facility for those unable to pay for baths recommended by their physician. Gradually Hot Springs came to be called "The American Spa." Such slogans as " Uncle Sam Bathes the World" and "The Nation's Health Sanitarium" were used o promote the city. Because minorities did not have equal access to the bathhouses on Bathhouse Row, African Americans opened their own facilities nearby beginning in 1905.

By 1921 the Hot Springs Reservation had become popular with vacationers and health remedy seekers. The new National Park Service's first director, Stephen Mather, convinced Congress to declare the reservation the 18th national park. Monumental bathhouses built along Bathhouse Row about that time catered to crowds of health-seekers. These new establishments, full of the latest equipment, pampered the bather in artful surroundings. The most expensive decorated their walls, floors, and partitions in marble and tile. Some rooms sported polished brass, murals, fountains, statues, and even stained glass. Gymnasiums and beauty shops helped cure-seekers in heir efforts to feel and look better.

The Army/Navy Hospital, now the Hot Springs Rehabilitation Center, is located just above the south end of Bathhouse Row. Its use of the hot spring water for treatments contributed to a boost in the bathing business during and immediately after World War II. By the 1950s changes in medicine led to a rapid decline in the use of water therapies. People also began taking driving vacations rather than traveling by train to a single destination. One by one, as business declined, the bathhouses began to close. The Buckstaff has been in continuous operation since it opened in 1912 and is the only bathhouse on Bathhouse Row that provides the traditional therapeutic bathing experience.

The Spa Today Despite the decline, bathing continues to be a popular pastime. Options available today still include tub bath, shower, steam cabinet, hot and cold packs, whirlpool, and massage. The Quapaw Bathhouse offers a modern-day spa with coed pools and spa services. Private businesses operate the Buckstaff and Quapaw, and their services are regulated and inspected by the National Park Service. You can get information about rates and services at the bathhouses or the Hot Springs National Park Visitor Center.

Do not pass up the opportunity to experience bathing in the hot spring waters. In a couple of hours you may find more relaxation and pleasure than you had ever imagined. You will join a long line of people who have bathed in the hot springs of Arkansas—a line that goes back centuries.

Hot Springs National Park is an unusual blend of a highly developed park in a small city surrounded by low-lying mountains abounding in plant life and wildlife. It is a park with a past, too. None of the bathhouses exists in their 1888 form today, although some of the names live on in present-day structures. New, fireproof structures took their places. The Fordyce Bathhouse sits on the site of the Palace. The water boy with his pot and cups was a familiar sight in the late 1800s. When staffing allows, rangers lead tours to the open hot springs. Spring, summer, and fall wildflowers like the wild phlox adorn the park's 26 miles of hiking trails. Gently rounded mountains are clad in green. The historic Buckstaff and Quapaw bathhouses offer a chance to relax in the hot spring water.

Water: The Main Attraction

During the Golden Age of Bathing over a million visitors a year immersed themselves in the park's hot waters. They then strolled Bathhouse Row with cups to "quaff the elixir" at decorative fountains. Today visitors fill bottles at jug fountains that dispense the odorless, flavorless, and colorless liquid. The water is tested regularly to ensure quality. Various open springs and the Hot Water Cascade above Arlington Lawn show how the area looked 200 years ago, before anyone built a bathhouse. All that steam gave rise to the vicinity's nickname, "Valley of Vapors." Today green boxes cover most of the 47 springs to prevent contamination. The water was first protected for all people to enjoy—not just a privileged few. That tradition of active use is very much alive.

What Makes This Water Hot?

Hot Springs National Park is not in a volcanic region. The water is heated by a different process. Outcroppings of Bigfork Chert and Arkansas Novaculite absorb rainfall in an arc from the northeast around to the east. Pores and fractures in the rock conduct the water deep into the Earth.

As the water percolates downward, increasingly warmer rock heats it at a rate of about 4°F every 300 feet. This is the average geothermal gradient worldwide, caused by gravitational compression and by the breakdown of naturally occurring radioactive elements. In the process the water dissolves minerals out of the rock. Eventually the water meets faults and joints leading up to the lower west slope of Hot Springs Mountain, where it surfaces.

Bathhouse Row Today

By the 1960s traditional bathing was in decline and the bathhouses began to close their doors. Unused, the buildings fell into disrepair. By 1985 only the Buckstaff remained open. In the 1980s the National Park Service began exploring ways to return the bathhouses and Bathhouse Row to the splendor, if not the function, of their heyday. This led to the Quapaw Baths reopening as a day spa with pools, and the Ozark Bathhouse to open as the Museum of Contemporary Art of Hot Springs.

In 2004 the park received the first of several appropriations to rehabilitate the vacant bathhouses and make them leasable. They are available for lease under the Historic Property Leasing Program. This is an example of merging the needs of the future with the preservation of the past, essential to the revitalization of the Bathhouse Row National Historic Landmark District and downtown Hot Springs.

Fordyce Bathhouse

In 1915 reviews proclaimed the Fordyce Bathhouse the best in Hot Springs. Now you can tour the Fordyce and see its original splendor. In 1989 the Fordyce, closed since 1962, reopened as the park visitor center and a museum.

After extensive restoration the bathhouse looks as it did in its early years. All of the women's side and some of the men's side of the building are outfitted with the furniture and equipment of the time: steam cabinets, Zander mechano-therapy equipment, tubs, massage tables, sitz tubs, Hubbard tub, chiropody tools, billiard table, Knabe piano, beauty parlor, and hydrotherapy equipment.

Visiting Hot Springs

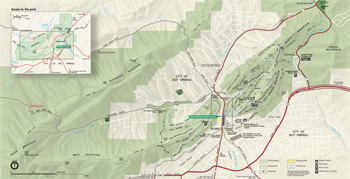

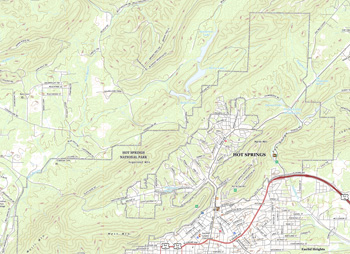

(click for larger maps) |

The park is about 55 miles southwest of Little Rock, in the Zig Zag Mountains. The park straddles a great horseshoe-shaped ridge formed by Sugarloaf Mountain on its north side, Music Mountain at its center, and West, Hot Springs, and North mountains on its south side. The visitor center is on the southeastern side of the horseshoe.

Dense forests of native oak, hickory, and short-leaf pine dominate the region. They provide habitat for many songbirds and small animals. Redbud and dogwood trees bloom in early spring in the forest understory. Flowering trees and shrubs with colorful foliage grace the hillsides at other times of year. In early summer the flowers of the southern magnolia trees lend historic Bathhouse Row a special beauty.

Visitor Center The restored Fordyce Bathhouse is in the middle of Bathhouse Row. Take a self-guiding tour of 23 furnished rooms restored to their appearance during the spa's heyday. Guided tours of the Fordyce take place daily. Exhibits and films tell the story of the hot springs and their use. In summer, rangers lead regular walks of the Bathhouse Row Historic District; in spring and fall, ranger-led walks are limited. Request guided group tours or American Sign Language Interpreters at least two weeks ahead.

Parking The park has no parking facilities on Bathhouse Row. Find parking in the city's adjacent historic district.

Accommodations The park campground in Gulpha Gorge, two miles northeast of downtown, has tables and grills for tent and RV campers; no showers. All sites have electric and water hookups; call for availability. Camping stays are limited to 14 days each year. No advance reservations; a self-registration and fee collection system is in effect. Find lodging at hotels, motels, bed-and-breakfast inns, boarding and rooming houses, and cottages on nearby lakes; call Hot Springs Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Things to Do Enjoy outdoor recreation year-round in Hot Springs' favorable climate. After relaxing in the thermal waters at one of the bathhouses, you may wish to stay longer than you planned. The Buckstaff and Quapaw bathhouses on Bathhouse Row are open to the public. The Ozark Bathhouse is now the Ozark Cultural Center, where our collection of artist-in-residence artwork is displayed. The building is open to the public by the Friends of Hot Springs National Park on weekends. You'll find activities throughout the year in the city of Hot Springs and the surrounding area—including thoroughbred horse racing, art galleries, music and film festivals, water sports, fishing, and camping. For a spectacular view of Hot Springs, visit the Hot Springs Mountain Tower. The 216-foot-high tower is open all year and is operated by a concessioner.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to a visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website.

Getting Here By vehicle use US 270, US 70, and AR 7. Greyhound buses service Hot Springs. Hot Springs Municipal Airport, three miles from Bathhouse Row, provides limited airline services. Little Rock National Airport provides service by larger airlines. City bus service is available.

Safety Drive slowly and carefully on the park's mountain roads; seat belts are required. Vehicles longer than 30 feet cannot use Hot Springs Mountain Drive. Hiking trails can be uneven; wear sturdy shoes. Watch out for stinging insects, ticks, snakes, and poison ivy.

Emergencies call 911

Regulations Vehicles, bicycles, skateboards, and any kind of skates are prohibited on sidewalks and trails. • Do not litter; help keep the park clean. • Build fires only in grills. • Leash your pets and clean up after them. • Obtain a permit from the park for commercial activity, weddings, or soliciting within the park. • All wildlife is protected in the park. Federal law prohibits removing plants, animals, rocks, or other natural or historic features. Report vandalism or graffiti to a ranger or the visitor center. • For firearms regulations check the park website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2019)

|

Establishment

Hot Springs National Park — March 4, 1921 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Search and Rescue Plan for Hot Springs National Park (undated)

A Survey of Architectural Resources of Hot Springs, Arkansas (Frederick D. Nichols, 1974)

An Historical Data Section for an Historic Structures Report on the Fordyce Bathhouse, Arkansas Hot Springs (Wilson Stiles, 1985)

Analyses of the Waters of the Hot Springs of Arkansas (HTML edition) (J.K. Haywood and Walter Harvey Weed, 1912)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Hot Springs National Park, 2009 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2012/241 (Jessica A. Luraas and David E. Bowles, February 2012)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Hot Springs National Park, 2009–2015 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2017/1126 (David E. Bowles, J. Tyler Cribbs and Janice A. Hinsey, November 2017)

Arkansas Sales Tax - Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (September 2, 1983 and August 16, 1990)

Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park HABS (undated)

Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park Draft (Earle B. Adams, July 19, 1983)

Bathhouse Row Adaptive Use Program

The Bathhouse Row Landscape: Technical Report 1 (June 1985)

The Superior Bathhouse: Technical Report 2 (June 1985)

The Hale Bathhouse: Technical Report 3 (June 1985)

The Maurice Bathhouse: Technical Report 4 (June 1985)

The Fordyce Bathhouse: Technical Report 5 (June 1985)

The Quapaw Bathhouse: Technical Report 6 (June 1985)

The Ozark Bathhouse: Technical Report 7 (June 1985)

Bathhouses (Brief Histories): Buckstaff • Fordyce • Hale • Lamar • Maurice • Ozark • Quapaw • Superior • Grand Promenade (undated)

"Cesspools," Springs, and Snaking Pipes (©Kathryn Carpenter, extract from Technology's Stories, Vol. 7 No. 1, March 2019)

Characteristics of thermal springs and the shallow ground-water system at Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5001 (Daniel S. Yeatts, 2006)

Condition Assessment and Treatment Plan for Libbey Memorial Physical Medicine Center: Pre-Design Services, Hot Springs National Park (STRATA Architecture Inc., June 30, 2022)

Condition Assessment and Treatment Plan for Maurice Bathhouse: Pre-Design Services, Hot Springs National Park (STRATA Architecture Inc., June 30, 2022)

Cultural Landscape Report and Environmental Assessment, Hot Springs National Park (Quinn Evans Architects, Mundus Bishop Design and Woolpert, Inc., January 2010)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park (2011)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Gulpha Gorge Campground, Hot Springs National Park (2012)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Hot Springs Scenic Highlands, Hot Springs National Park (2024, rev. 4/2024)

Effects of Climate and Land-Use Change on Thermal Springs Recharge—A System-Based Coupled Surface-Water and Groundwater-Flow Model for Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2021-5045 (Rheannon M. Hart, Scott J. Ikard, Phillip D. Hays and Brian R. Clark, 2021)

Evaluation of Existing NPS Flood Preparedness Plan and Recommendations for the Integration of an Automated Early Warning System: Hot Springs National Park, Hot Springs, Arkansas (Lex A. Kamstra and Patricia Hagan-Chagnon, January 1993)

Existing and Historic Bathhouse Row Landscape Study, Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (Robert D. Wright and Claude H. O'Gwynn, September 25, 1987)

Ferns of the Tufa Deposits on Hot Springs Mountain, Hot Springs National Park: Inventory, Status, and Maintenance (W. Carl Taylor, August 1, 1981)

Finding Aid: Hot Springs National Park Collection (History Associates Inc., 2011)

Fire in Folded Rocks: Geology of Hot Springs National Park (Jeffrey S. Hanor, 1980)

Fish Community Monitoring at Hot Springs National Park: 2009 Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2012/235 (Hope R. Dodd and Samantha K. Mueller, February 2012)

Fordyce Bathhouse Visitor Center (May 8, 1989)

Fordyce Baths Coupons (undated)

Forest Community Monitoring Baseline Report, Hot Springs National Park NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2008/081 (Kevin James, February 2008)

Foundation Document, Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (June 2012)

Foundation Document Overview, Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (June 2014)

Frederick Law Olmsted (June 20, 1989)

General Management Plan / Development Concept Plan: Hot Springs National Park, Garland County, Arkansas (June 1986)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Hot Springs National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2013/741 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, December 2013)

Geologic Sketch of Hot Springs, Arkansas (Water Harvey Weed, 1912)

Geology of the Area (undated)

Grand Opening of the Fordyce Bathhouse Visitor Center (May 1989)

Historic American Engineering Record

Gulpha Gorge Bridges (Nos. 1-4) HAER No. AR-104 (Lola Bennett. 2007)

Historic Furnishings Report: Fordyce Bathhouse, Hot Springs National Park (Carol A. Petravage, 1987)

Historic Structure Report: Superior Bathhouse, Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (Chamberlain Architects and The Collaborative, November 2004)

Historic Structures Report: Hot Springs National Park (Cromwell, Neyland, Truemper, Millett & Gatchell, Inc., November 1973)

History of Hot Springs National Park (Forrest M. Benson and Donald S. Libbey, undated)

Hot Springs National Park (United States Railroad Administration, 1919)

Hot Springs National Park: A Brief History of the Park (Sharon Shugart, November 2003)

Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (1917)

Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (1929)

Hot Springs National Park Through the Years: A Chronology of Events (Sharon Shugart, 2004)

Information Sheets

Bird Checklist (February 1983)

Wildflower Calendar (undated)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Hot Springs National Park: Year 1 (2009) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2010/288 (Mary F. Short, Craig C. Young, Chad S. Gross and Jennifer L. Haack, February 2010)

Invitation to Grand Opening of the Fordyce Bathhouse Visitor Center (May 1989)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Hot Springs National Park (2015; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Book — All About Bats, Hot Springs National Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Lamar Bath House Coupons (undated)

Landscape Management Plan: Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park (September 1989)

Legend of the Quapaw Baths (©Eastern National Park & Monument Association, 1984)

Lindbergh Kidnapping (1935)

Listing of the Comments on Fires from the Superintendent's Monthly and Annual Reports, Hot Springs National Park (Jeff Ohlfs, undated)

Listing of the Comments on IPM from the Superintendent's Monthly and Annual Reports, Hot Springs National Park (Jeff Ohlfs, undated)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Hot Springs National Park (December 2008)

Looking Backward Through Tattered Curtains: The History of a Landmark (Audrey Wenger McCully, 1986)

More Than Meets The Eye: The Archeology Of Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report Series No. 102 (William J. Hunt, Jr., 2008)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Bathhouse Row (Laura Soullière Harrison, 1985)

New Wonders of Radium (extract from New York American and Journal, February 14, 1904)

Out of the Vapors: A Social and Architectural History of Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park (John C. Paige and Laura Soullière Harrison, 1987)

Overview of Historical Research: Annotated Bibliography and Review of Plans and Future Studies, Hot Springs National Park (Jane E. Scott, June 1978)

Program for Grand Opening of the Fordyce Bathhouse Visitor Center (May 13, 1989)

Report of an Analyses of the Waters of the Hot Springs on the Hot Springs Reservation, Hot Springs, Garland County, Ark. and Geological Sketch of Hot Springs, Arkansas Senate Document No. 282, 57th Congress, 1st Session (J.K. Haywood and Walter Harvey Weed, 1902)

Report of the Commission Regarding the Hot Springs Reservation of the State of Arkansas (1878)

Report of the Medical Director of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior (1912)

Reports of Regional Geologist on Hot Springs National Park

Report of Regional Geologist on Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (Chas. E. Gould, June 25, 1936)

Second Geological Report on Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (Chas. E. Gould, March 12, 1937)

Third Geological Report on Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (Chas. E. Gould, July 10, 1937)

Fourth Geological Report on Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (Chas. E. Gould, April 12-13, 1938)

Reports of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior

Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior (1887)

Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior (1899)

Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year Ended June 30, 1906 (HTML edition) (1906)

Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior (1910)

Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior (HTML edition) (1911)

Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1914 (HTML edition) (1914)

Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1915 (HTML edition) (1915)

Seed Report on Ricks Estate Dam, National Park Service, Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas, Southwest Region (August 1984)

Some Account of the Hot Springs of Arkansas (A.J. Wright, extract from The New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol. 17:796-808, 1860-61)

Statement for Management: Hot Springs Reservation, Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas (Revised 1988)

Structural Fire History Summary (Jeff, Ohlfs, April 7, 1988)

Testimony Taken Before the Committee on Expenditures in the Interior Department, relative to Certain things connected with Government property at Hot Springs, Ark. Mis. Doc. No. 58 (House of Representatives, 48th Congress, st Session, June 17, 1884)

The Collecting Area of the Waters of the Hot Springs, Hot Springs, Arkansas (A.H. Purdue, extract from The Journal of Geology, Vol. 18 No. 3, April-May 1910)

The Fishes of Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas, 2003 USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5126 (James C. Petersen and B.G. Justus, 2005)

The Fordyce Baths (undated)

The Hot Springs of Arkansas (Kirk Bryan, extract from The Journal of Geology, Vol. 32 No. 6, August-September 1924)

The Hot Springs of Arkansas — America's First National Park: Administrative History of Hot Springs National Park (Ron Cockrell, 2014)

The Hot Water Supply of the Hot Springs, Arkansas (Kirk Bryan, extract from The Journal of Geology, Vol. 30 No. 6, August-September 1922)

The Impact of the Civil War on Hot Springs, Arkansas (Wendy Richter, undated)

The Legend of the Quapaw Cave, Reexamined (Sharon Shugart, undated)

The Maurice: The Bath House Beautiful (undated)

The Ral Spring Site (undated)

The Waters of Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas—Their Nature and Origin USGS Professional Paper 1044-C (M.S. Bedinger, F.J. Pearson, Jr., J.E. Reed, R.T. Sniegocki and C.G. Stone, 1979)

Transcription and Translation of Hot Springs Passage in the Account of the Hernando de Soto Expedition by the Gentleman from Elvas (April 24, 1987)

Turning the Corner: The Landscape History of the Administration Building, Hot Springs National Park (Laura Soullière Harrison, January 1990)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas: Project Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR—2015/1075 (David D. Diamond, Lee F. Elliott, Michael D. DeBacker, Kevin M. James, Dyanna L. Pursell and Alicia Struckhoff, November 2015)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas: 2007–2014 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2017/1104 (Sherry A. Leis, May 2017)

hosp/index.htm

Last Updated: 09-Apr-2025