|

Lake Mead National Recreation Area Arizona-Nevada |

|

NPS photo | |

America's First Playground

STRIKING LANDSCAPES AND BRILLIANT BLUE WATER await you at Lake Mead National Recreation Area. From the time Hoover Dam was completed in 1936, Lake Mead's cool waters have drawn people looking for relaxation and fun in the desert. Lake Mohave joined the complex when Davis Dam was completed in 1951. And in 1964, both lakes became part of the first national recreation area in the National Park Service. Today 1.5 million acres attract over six million people each year.

MODERN EXPLORERS find solitude and beauty any time of year. Hot weather beckons you to the lakes, where you can fish, swim, and boat to less-visited sites. Cooler weather entices you to explore the Mojave Desert on foot, using established trails or traveling crosscountry. The park's website (www.nps.gov/lake) offers many ideas for your adventures.

This fabulous playground spreads across a landscape exposing the geologic history of Earth. You can see billion-year-old rocks, lava that flowed millions of years ago, and the remains of ancient seas. Other national parks have some of these geologic features, but at Lake Mead National Recreation Area the rangers say you can see "millions of years in one place."

Across it all lies the Mojave Desert, a dry land full of plants and animals that have adapted to thrive with little water. The desert makes up 87 percent of the park; the rest is water.

Lakes Mead and Mohave hold more than four trillion gallons of water, most of it coming from the Colorado River. Lake Mead is the largest and one of the cleanest reservoirs in North America. Over 25 million people depend on this lake for their drinking water.

This unusual combination of desert and water is home to 900 species of plants and 500 species of animals, including 24 that are rare and threatened. Plants of one kind or another bloom throughout the year. As you notice the diversity of life, think about how they manage to survive.

Eight developed visitor areas welcome you with a variety of services like marinas, docks, restaurants, and campgrounds. Enjoy ranger-led hikes and programs. Explore nine wilderness areas and miles of undeveloped lakeshore. They provide places of solitude, quiet, and beauty that will refresh and delight you.

Life at Lake Mead.

The ZEBRA-TAILED LIZARD and collared lizard are among the 19 species of lizards living in the park. They are active when the temperature is above 70°F.

A COYOTE will likely wait for cooler evening temperatures to look for food. Desert coyotes are about half the size of other coyotes. Being smaller means needing less water—an advantage in the desert.

HEDGEHOG CACTUS forms barrels covered with spines. The flowers bloom in spring and vary from this magenta to a deep red. This cactus is often seen in the Mojave Desert.

Look for the GREAT EGRET standing in shallow water, waiting for a frog, fish, or other aquatic animal to move. When a prey moves, the egret stabs the water with its sharp beak and swallows a meal.

A GOLDEN EAGLE lifts off when BIGHORN RAMS clamber into sight. Like all bighorn sheep, desert bighorns have concave hooves that can grip rocks, allowing the sheep to scramble up steep terrain.

Watch out for NOTCH-LEAF PHACELIA. Its sticky hairs might give you a rash. Those hairs filter the intense desert sunlight, keeping the plant cooler and conserving its water.

A Hard Place with Soft Edges

To describe the how and why of the rocks here, geologists use words like crash, strike, smash, collide. Massive blocks of Earth's crust have broken apart, crashed together, slipped past each other, spread apart, and been forced up or down thousands of feet. The heat of magma (molten rock) deep below the surface powers this action, which has been ongoing for almost two billion years.

The softer action of seas and lakes also has been changing the surface of this land. Vast, shallow seas moved in and away. Lakes rose and evaporated. Each left behind layers of sediment that hardened into rock. The only lakes now are the two that humans have created.

These new lakes, Mead and Mohave, continue to change this landscape. As lake waters soften canyon walls, the rocks erode. Sediment drops to the bottoms of the lakes.

As you explore Lake Mead country, consider how rock and water have created this land of hard places and soft edges.

I would defy anyone to make a journey by boat through those still, weird chasms and down that yet mysterious River, and not be brought under by their influence.

—John Wesley Powell

COLORADO RIVER

HIDDEN RIVER From its snowy beginnings in the Rockies, the Colorado River runs more than 800 miles before flowing out of the Grand Canyon into lakes Mead and Mohave. The lakes rise hundreds of feet above the old riverbed, which is still the border between Arizona and Nevada. Davis Dam, at the park's southern edge, releases the river to flow south toward Mexico.

SHARP TURN SOUTH Just above where Hoover Dam is today, the Colorado River took a sharp turn south. This marks a place where two massive faults meet. In five million years, which is a blip of geologic time, the Colorado cut through 1.3 billion years of rocks to expose the history of the Earth.

CHANGES Today the river is bringing less water into the park than in previous centuries. Less snow is falling in the mountains of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado, which means less water flowing into the streams and rivers that feed the Colorado River. What this means for the Lake Mead area remains to be seen.

In the American Southwest, I began a lifelong love affair with a pile of rock.

—Edward Abbey

THE ROCKS

VOLCANICS The volcanic events that shape the present-day Lake Mead National Recreation Area began 18 million years ago. Great volcanoes formed during this time; their remains dominate the landscape.

ANCIENT SEAS Billions of tiny creatures, like trilobites, thrived in these shallow seas. As they died, their skeletons collected on the bottom, forming layers of sediment that hardened as limestone.

FAULT MOVEMENT In several places, blocks of mountains broke along faults in Earth's crust and moved miles apart. Wilson Ridge may have lost its top layer this way.

UPLIFT Over eons, geologic forces have pushed up rocks formed hundreds of millions of years ago. Look for steep cliffs of light-colored limestone from ancient seas and darker Precambrian rock from the beginning of time.

Here are the long heavy winds and breathless calms....

—Mary Austin, The Land of Little Rain

LIVING HERE

One hundred miles west of Lake Mead National Recreation Area, the Sierra Nevada soars 14,000 feet above the MOJAVE DESERT. These massive mountains block moisture from the Pacific Ocean, creating a "Land of Little Rain."

HOW PLANTS SURVIVE The Joshua tree is a kind of yucca living in higher elevations of the Mojave. Pollinated only by the yucca moth, it blooms after a wet winter with freezing temperatures. The creosote bush dominates the lowlands. Its leaves are coated with resin to hold in water; the resin gives off a scent like "rain in the desert." Wildflower seeds rest in the soil until the next rainy season, then they grow fast and carpet the desert floor with color.

HOW ANIMALS SURVIVE During hot weather, desert tortoises stay in burrows to stay cool. They emerge after a rain to drink at puddles. A jackrabbit's blood cools off while through its big ears.

THE HUMAN STORY

Spirit Mountain, a sacred site to some Native Americans, rises in the southern part of Lake Mead National Recreation Area. Ten thousand years ago, people hunted and gathered food from the desert. Later people learned to use yucca to make baskets and ropes. They also learned to irrigate and grow crops.

NEW PEOPLE

By the 1700s, native people began encountering European Americans when

fur traders, explorers, and a few settlers came into the desert. In the

mid-1800s, steamboats traveled up the Colorado River from Mexico. They

brought more settlers and supplies deep into the Mojave Desert. Soon

Mormons started towns along the Colorado, Virgin, and Muddy rivers.

After gold and silver were found in 1867, people crowded the towns. They also established ferry crossings at Temple Bar and Pearce Ferry on the Colorado River.

BOULDER DAM

By the early 1900s, people wanted protection from Colorado River floods.

A dam was the solution. It could regulate river flow, generate

electricity, and provide water for drinking and irrigation. Each month,

over 3,500 people worked on the dam. Tourists also came to see the

world's tallest dam being built. By 1936, the Boulder Dam was done. Now

called Hoover Dam, it is not the tallest in the world anymore. But it

still draws visitors.

AFTER THE DAM

Now people had a cool lake to enjoy in the middle of the hot desert.

Over two million flocked to Boulder Basin each summer. Tourism grew when

Lake Mohave formed after Davis Dam was finished in 1951.

TODAY

Lake Mead National Recreation Area continues to draw people from around

the world. They come to see Hoover Dam, play in the two lakes, and hike

the many desert trails. Spirit Mountain still draws native people

seeking connection to their ancestors. This sacred mountain is in one of

the nine wilderness areas offering solitude and beauty to those who take

the less-traveled routes.

Exploring Lake Mead National Recreation Area

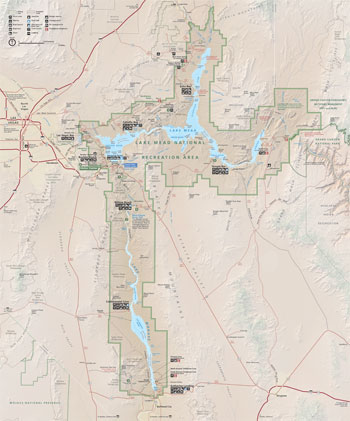

(click for larger map) |

LIBERTY BELL ARCH Lace up your boots for a walk into the wild country on the rim of the Black Canyon. This arch formed when a stream cut through the softer rock beneath a hard volcanic layer. Explore geologic history by hiking other areas of the park.

REDSTONE Walk among spectacular red rocks, which are sand dunes formed about 200 million years ago. At that time this area would have looked like the Sahara Desert. Iron particles held the sand together and oxidized over time to turn the rocks red.

GRAPEVINE CANYON Look for petroglyphs as you enjoy a short walk into Bridge Canyon Wilderness. A seasonal spring near this petroglyph probably attracted early native people to the site. Perhaps you will see desert bighorn sheep on the rocks.

WILLOW BEACH Come to this secluded visitor area to explore the Black Canyon. The canyon is named for the dark volcanic rock that flowed and cooled 13 to 16 million years ago. The Colorado River cut through the rocks, revealing the geologic history of this area.

TEMPLE BAR Launch your boat in the shadow of The Temple, rising high above the water. Its golden layers are solidified sediments from ancient seas. Far from the crowds of Boulder Basin, this area provides access to the remote eastern reaches of Lake Mead.

HISTORIC RAILROAD TRAIL Follow the route of trains that hauled supplies to build Hoover Dam. Enjoy spectacular views of Boulder Basin.

BLACK CANYON This steep-walled canyon begins below Hoover Dam. You can launch a water-based exploration from several sites around Lake Mohave. With its cold moving water and steep walls, the Black Canyon retains a feel of the old Colorado River.

Congress has set aside nine WILDERNESS areas in Lake Mead National Recreation Area under the 1964 Wilderness Act. Preserving wilderness shows restraint and humility, and benefits generations to come. Wilderness designation protects forever the land's wilderness character, natural conditions, opportunities for solitude, and scientific, educational, and historical values. To learn more about the National Wilderness Preservation System, visit www.wilderness.net.

Seeing It Safely

On the water or in the desert, stay safe by following these guidelines. For more details, go to the park's website (listed under More Information) or ask at an entrance station or the visitor center.

WATER SAFETY

WATCH THE WEATHER Watch for storm warning flags at marinas. • Expect sudden winds and high waves. • Expect lightning. • If you cannot get off the water, seek shelter in a cove. • Monitor marine radio channel 16.

IN THE WATER Life jackets are recommended for anyone playing in or near water. • Pool toys are dangerous. • Watch your children. • Swim at your own risk; no lifeguards. • Know and follow all water safety rules for your water activity.

ON A BOAT An easy-to-reach, approved life jacket must be available for every person on board. • Children 12 and under must wear a life jacket. • It is illegal to operate a boat while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. • Water levels change frequently during the year. Approach shore cautiously; watch for shallows and submerged debris. • Never let a passenger ride on the bow.

WATER SKIING Skiers must wear life jackets. • An observer other than the boat operator must be on the boat. • Display a ski flag when a skier is in the water.

SCUBA DIVING Always dive with a buddy. • Mark your location with a diver's flag.

DESERT SAFETY

FLASH FLOODS AND LIGHTNING Flash floods can roar into areas untouched by rain. Never camp in a wash or a lowlying area; never drive across a flooded road. • Stay out of open areas where lightning may strike.

CLIMATE AND HEAT June through August, temperatures are often above 100°F. Avoid strenuous activities during the day. • Know the signs of heat exhaustion and heat stroke. • January and February highs average 50°F; lows can drop below 32°F. • Drink water often; your body can lose fluids quickly.

WILDLIFE AND PLANT CAUTIONS Scorpions and rattlesnakes will leave you alone unless disturbed or cornered. • Wear sturdy shoes; do not put your hands or feet into a place you can't see. • Do not submerge your head in thermal waters—a microorganism in some hot springs can cause infection and sometimes death. • Avoid oleander, its wood, and water from ditches where it grows.

MINES AND TUNNELS Do not enter old mines and tunnels; shafts and rotten timbers are dangerous.

HUNTING AND FIREARMS You must have the appropriate license and obey all regulations. • Hunting and firearms regulations are on the park website.

DRIVING Off-road driving is prohibited. Use backcountry road maps from the visitor center, entrance stations, or park website.

PETS Keep pets on a leash (six-foot maximum length). • Never leave pets alone, especially in a vehicle. Temperatures inside can climb to 160°F; a pet can die quickly. • Pets are prohibited on some designated beaches and in public eating places and public buildings.

PROTECTED FEATURES Federal law protects all natural and cultural features including rocks, plants, animals, and artifacts.

ACCESSIBILITY We strive to make facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information ask at an entrance station or the visitor center, or check the park website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2016)

Documents

15 Non-Native Plants at Lake Mead National Recreation Area (Carrie Norman, undated)

Acoustic Monitoring 2007-2012, Lake Mead National Recreation Area NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/NRTR—2013/785 (Jessie Rinella, July 2013)

Amphibians, Reptiles and Mammals of the Lake Mead National Recreation Area LAKE Technical Report No. 2 (Jeffrey Schwartz, George T. Austin and Charles L. Douglas, December 1978)

Annual Report: 1986 — Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit (December 31, 1986)

Archeology of Lake Mead National Recreation Area: An Assessment Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 9 (Carole McClellan, David A. Phillips, Jr. and Mike Belshaw, 1980)

Authorities for Water Resources Decision Making on the Colorado River Draft (April 1991)

Balancing the Mandates: An Administrative History of Lake Mead National Recreation Area (Hal K. Rothman and Daniel J. Holder, June 2002)

Birds of the Lake Mead National Recreation Area LAKE Technical Report No. 1 (John G. Blake, November 1978)

Brief: Invasive Mussels Found in Lake Mead (undated)

Concealed Firearms, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (undated)

Construction of Boulder Dam (Tenth Edition, 1934)

Firearms Fact Sheet, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (December 2008)

General Management Plan Amendment / Environmental Assessment, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (September 2005)

Foundation Document, Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Arizona-Nevada (September 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Arizona-Nevada (January 2015)

Historic Resource Study, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (Mike Belshaw and Ed Peplow, Jr., August 1980)

Historic Resource Study (Volume II): Mines and Mining Districts in Lake Mead National Recreation Area / Historic Sites Within Lake Mead National Recreation Area Deemed Ineligible for National Register Nomination (Michael Belshaw and Nick Scrattish, July 1983)

Investigation of Plant Colonization and Succession in the Lake Mead Shoreline Drawdown Zone (Cayenne Engel, 2013)

Junior Ranger Guide and Activity Book, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (2002; for reference purposes only)

Lake Mead National Recreation Area: An Ethnographic Overview Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology No. 3 (David E. Ruppert, 1976)

Minerals Management Plan: Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Arizona-Nevada (September 1988)

Monitoring Ecosystem Quality and Function in Arid Settings of the Mojave Desert USGS Scientific Investigation Report 2008-5064 (Jayne Belnap, Robert H. Webb, Mark E. Miller, David M. Miller, Lelsey A. DeFalco, Philip A. Medica, Matthew L. Brooks, Todd C. Esque and Dave Bedford, 2008)

Museum Management Plan, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (Kent Bush, Blair Davenport, Lynn Marie Mitchell, Diane Nicholson and Rosie Pepito, 2005)

Naegleria fowleri, A Public Health Risk, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (October 5, 2012)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Horse Valley Ranch (Waring Ranch) (Gordon Chappell, February 23, 1983)

Willow Beach Gauging Station (F. Ross Holland, Jr. and Gordon Chappell, March 14, 1983)

Grand Wash Archeological District (Keith Anderson, David A. Phillips, Jr. and Carole McClellan, March 1, 1979)

Grapevine Canyon Petroglyphs (Deni Seymour and Kay Simpson, September 1982; Roger E. Kelly, ed., December 1983)

Homestake Mine (Deni J. Seymour and Kay Simpson, September 1982; Roger E. Kelly, ed., July 1984)

Pueblo Grande de Nevada ("Lost City") (James C. Maxon and Lysenda Kirkberg, c1982)

Spirit Mountain (Cynthia Ellis and Stanton Rolf, May 30, 1999)

Natural Resource Condition Assessments for Six Parks in the Mojave Desert Network NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MOJN/NRR-2019/1959 (Erica Fleishman, Christine Albano, Bethany A. Bradley, Tyler G. Creech, Caroline Curtis, Brett G. Dickson, Clinton W. Epps, Ericka E. Hegeman, Cerissa Hoglander, Matthias Leu, Nicole Shaw, Mark W. Schwartz, Anthony VanCuren and Luke Z. Zachmann, August 2019)

Newberry Mountains Archeological Inventory 1993-1994: A Section 110 Planning Survey and Site Assessment, Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Clark County, Nevada (Gregory L. Fox, 1994)

Park Newspaper: 1991 • Spring/Summer 2001 • Summer/Fall 2002 • Summer 2004 • Winter/Spring 2010 • Fall 2011 • Summer 2012 • Fall/Winter 2012-13 • Spring 2013 • Winter/Spring 2014 • Summer 2014 • Spring 2015 • Fall/Winter 2015-16 • Spring 2016 • Fall/Winter 2016-17 • Spring 2017

Recent Vegetation Changes Along the Colorado River Between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead, Arizona U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1132 (Raymond M. Turner and Martin M. Karpiscak, 1980)

Statement for Management, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (May 1993)

Strategic Plan: 1995-1999, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (1995)

Sustainable Lower Water Access Plan/Environmental Assessment Newsletter, Lake Mead National Recreation Area (November 2022)

The Archeological Excavations at Willow Beach, Arizona University of Utah Anthropological Papers No. 50 (Albert H. Schroeder, April 1961)

The Effects of Tamarisk Removal on Diurnal Ground Water Fluctuations NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-96/93 (Richard Inglis, Curt Deuser and Joel Wagner, November 1996)

The Influence of Late Cenozoic Stratigraphy on Distribution of Impoundment-related Seismicity at Lake Mead, Nevada-Arizona Journal of Research of the U.S. Geological Survey (R. Ernest Anderson and R.L. Laney, Vol. 3 No. 3, May-June 1975)

The Oasis (Mojave Desert Network)

2022: Spring

The Road Inventory of Lake Mead National Recreation Area (April 1999)

The Story of Boulder Dam Conservation Bulletin No. 9 (1941)

The Story of Hoover Dam Conservation Bulletin No. 9 (1955)

Vascular Plants of the Lake Mead National Recreation Area LAKE Technical Report No. 3 (James S. Holland, Wesley E. Niles and Patrick J. Leary, February 1979)

Vegetation Classification at Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Mojave National Preserve, Castle Mountains National Monument, and Death Valley National Park: Final Report (Revised with Cost Estimate) NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MOJN/NRR-2020/2178 (Julie M. Evens, Kendra G. Sikes and Jaime S. Ratchford, October 2020)

Vegetation Mapping of Lake Mead National Recreation Area NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MOJN/NRR—2016/1344 (David E. Salas, Joe Stevens, Julie Evens, Dan Cogan, Jaime S. Ratchford and Daniel Hastings, December 2016)

Welcome to Lake Mead Country (Arizona Highways, Vol 59 No. 5, May 1983; ©Arizona Department of Transportation)

lake/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025