|

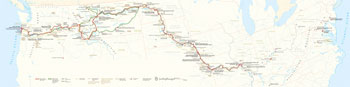

Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail IA-ID-IL-IN-KS-KY-MO-MT-NE-ND-OH-OR-PA-SD-WA-WV |

|

NPS photo | |

The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by it's course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado or any other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.

—President Thomas Jefferson, 1803

They Journeyed On

The Lewis and Clark expedition is the most universally known event of American exploration. Because of its unparalleled success and the seeming ease with which it was carried out, we tend to overlook or to underrate the hardships and dangers that confronted the Corps of Discovery. The explorers met these circumstances with determination and good sense. Neither foolhardy nor timid, Lewis and Clark were deliberate and quick-witted, and as inventive and creative as situations demanded.

For 28 months the Corps of Discovery faced many challenges. There were dramatic incidents with Indians, notably a face-down with Teton Sioux and a bloody encounter with Piegan Blackfeet. At times, circumstances taxed the morale of the party, and the many references in the journals kept by Lewis and Clark reflect their concern about the men's spirit. As the strain of physical exertion mounted, so did the likelihood of accidents and illness. Exhaustion led to mishaps and mistakes. Burdened by arduous tasks, hampered by inclement weather, and slowed by the hardships of the terrain, everyone began to feel the press of time. The captains' cool-headedness in the face of such hardships accounts for much of the success of the expedition.

Probably the challenges that Lewis and Clark faced were not entirely new to them. Both had met like challenge; during their years of military service. Leading men on dangerous missions in wilderness settings against potentially hostile Indians was, after all a task of most young officer of that era. But crossing a continent challenged them in ways that earlier experience had not entirely prepared them for. The expedition called for them to make difficult decisions under circumstances previously unmatched and not encountered by their contemporaries Cut off from the support and reliable advice of season professionals, Lewis and Clark had to depend on their own judgment. In this they proved themselves entirely worthy of President Jefferson's trust, and they are still to be admired for their resourcefulness and ingenuity. Jefferson could not have wanted better leaders for the young nation's first great venture into western exploration.

—Gary E. Moulton, editor,

The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery

The Corps of Discovery

Meriwether Lewis began preparing for the military expedition in March 1803. He ordered custom-made weapons from the US armory in Harpers Ferry. He also supervised construction of a collapsible iron boat frame, designed to be covered with animal skins, that he thought might prove useful. In Pittsburgh he ordered a keelboat and got a Newfoundland dog he named Seaman. In Philadelphia he took crash courses in medicine, natural history, and the use of scientific instruments. He also bought clothing, trade goods, paper, medicines, and other supplies. In Lancaster he learned to use celestial navigation tools.

From Philadelphia Lewis wrote to William Clark, a fellow Virginian under whom he once served, asking him to join as co-commander. Clark, brother of George Rogers Clark of American Revolution fame, accepted and began to recruit "some good hunters, stout, healthy, unmarried men, accustomed to the woods, and capable of bearing bodily fatigue in a pretty considerable degree."

As finally assembled for the upriver journey in May 1804, the Corps of Discovery numbered 44 men of diverse backgrounds. Most were US Army enlisted men. Others were backwoodsmen. A few were French boatmen who were hired to pilot the keelboat up the Missouri and who also knew how to handle the smaller boats called pirogues. Most Corps members were young, single, accustomed to hard labor, and had useful skills. One, a black man named York, was held in slavery by William Clark. Two men had blacksmithing experience, and one knew carpentry. Others knew Indian languages, and some were excellent hunters. All demonstrated an ability to bear extreme hardship.

One of the most valuable members, George Drouillard, an outstanding scout, hunter, and interpreter, spoke several Indian languages. A total of 33 were designated the "permanent party" and intended to make the entire journey. The remainder, the "return party," were to be sent back down the Missouri midway through the voyage, with maps, notes, and specimens of plants, animals, and minerals they had so far collected.

To the Shore of the Pacific

The journey began on May 14, 1804, as the Corps of Discovery left Camp River Dubois in the keelboat and two pirogues, crossed the Mississippi River, and headed up the Missouri. Over the next 28 months they would traverse 8,000 miles of land and water, about which they knew next to nothing, in search of a fabled Northwest passage that had eluded explorers for hundreds of years.

The 2,540-mile Missouri was not an easy river to travel. The Corps tried to maintain 14 to 20 miles a day, but some days conditions limited them to four or five miles. At times the men battled powerful currents and turbulent waters that brought trees or branches into the river and caved in riverbanks with little or no warning. Summer heat was unbearable, and they were often plagued by insects.

Lewis, who had received some medical training, treated many illnesses, injuries, and ailments such as sore feet, toothaches, boils, and snakebites. Remarkably, only one member of the expedition died during the entire trek—Sgt. Charles Floyd on August 20, 1804.

Both captains kept journals, meticulously recording the distances they traveled, navigational measurements that would later form the basis for maps of the journey, and observations of topography, ethnography, mineral resources, and hundreds of plants and animals previously unknown to western science.

In November the expedition set up winter quarters near the junction of the Knife and Missouri rivers, in present-day North Dakota, 1,609 miles from Camp River Dubois. They built Fort Mandan near the five villages of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes, who provided valuable knowledge of the country west to the Rocky Mountains. Here Lewis and Clark recruited as interpreters Toussaint Charbonneau, a 44-year-old French-Canadian trapper, and his 16-year-old Shoshone wife Sacagawea. In February 1805 Sacagawea gave birth to a boy she and her husband named Jean Baptiste. Her presence, along with the baby's and that of a black man, was a curiosity to the tribes.

Lewis and Clark would not have made it to the Pacific and back without the help of Indian tribes like the Mandan and Hidatsa, Shoshone, Nez Perce, and Clatsop. Over the course of the expedition the Corps came into contact with nearly 50 different tribes.

They often provided food, trading opportunities, knowledge of the lands ahead, and experienced guides. Only once, in July 1806 with a party of Piegan Blackfeet, did the expedition have an encounter that led to violence.

In early April 1805 Lewis and Clark sent the keelboat—too large to navigate the Upper Missouri—back to St. Louis with letters, dispatches, maps, reports, and a large collection of zoological, botanical, and ethnological specimens and artifacts for President Jefferson. The rest of the Corps continued up the Missouri in two pirogues and six recently built canoes.

Over the next several months they would experience hunger, fatigue, privation, and sickness as they forged westward past the mouth of the Yellowstone River and into what is now Montana, then on to the Great Falls. The falls portage took three weeks.

At the Three Forks of the Missouri, they followed the western, or Jefferson, fork. In August, after reaching Lemhi Pass on the Continental Divide, Lewis and Clark met Sacagawea's relatives (the first Indian contact since they left Fort Mandan), who provided the expedition with horses and guided them over the difficult mountain ranges of Idaho to the Salmon River and to the Bitterroot Valley.

From a point they called "Travelers' Rest," near present-day Missoula, Montana, they crossed Lolo Pass to the Clearwater River, which flowed into the Snake and then the Columbia. The Corps finally reached the Pacific in mid-November 1805. They were 4,134 miles from Camp River Dubois, according to William Clark.

At the mouth of the Columbia they built Fort Clatsop, named after a local Indian tribe, and settled into winter quarters. Rainy weather, tainted food, and insects plagued the expedition all winter.

While Lewis and Clark worked on their journals and maps, the rest of the Corps prepared for the return trip by boiling ocean water for salt, hunting, and preparing elk hides from which to make moccasins and clothing.

Return to St. Louis

The Corps of Discovery left Fort Clatsop on March 23, 1806. Drouillard and a party of hunters were sent out ahead while the rest of the group traveled up the Columbia. A Wallowa leader showed them a shortcut, enabling them to bypass the Snake River and save 80 miles.

On June 24, after spending a month with the Nez Perce waiting for the winter snows to melt, the Corps set out along the Lolo Trail for the Bitterroot Mountains. On July 3, after crossing the mountains via Lolo Pass and stopping at Travelers' Rest, Lewis and Clark split the men into two main groups so as to explore more of the territory. Lewis' group continued over what is now called Lewis and Clark Pass and reached the Missouri near the Great Falls. Lewis and three others then explored the Marias River, during which the only deadly encounter between the expedition and Indians occurred. Clark's group generally retraced the outbound route to the Three Forks of the Missouri and then overland to the Yellowstone River, which they followed to its junction with the Missouri. There on August 12, 1806, Clark was reunited with Lewis and his party. The expedition proceeded down the Missouri to St. Louis where, on September 23, 1806, the Corps was greeted with as much fanfare as the settlement could muster. Of the expedition's accomplishments, Jefferson wrote: "Messrs. Lewis and Clark, and their brave companions, have by this arduous service deserved well of their country."

1803

President Thomas Jefferson picks Meriwether Lewis to lead an expedition through the Northwest.

Spring/Summer

Lewis invites William Clark to join the expedition and share the command. The news of the Louisiana Purchase is announced. A large keelboat ordered by Lewis is constructed in the Pittsburgh area. Lewis meets Clark at the Falls of the Ohio.

Fall/Winter

Congress ratifies the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the nation's size. Lewis and Clark establish Camp River Dubois on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River, where they prepare the men for a spring departure.

1804

May 14

Expedition begins and "proceeded on under a jentle brease up the Missourie."

July 4

Expedition marks first 4th of July west of the Mississippi by firing the keelboat's cannon, and naming Independence Creek near present-day Atchison, KS.

August 3

Corps holds first official council between US representatives and Otoe-Missouria Indians near present-day Fort Atkinson State Park, NE.

August 20

Near present-day Sioux City, IA, Sgt. Charles Floyd dies of probable burst appendix. Captains name the hilltop where he is buried "Floyd's Bluff" and a nearby stream "Floyd's River."

August 30

Friendly council held with Yankton Sioux.

September 7

The men successfully flush a prairie dog out of its hole for shipment back to Jefferson.

September 25

Misunderstanding with Teton Sioux leads to a confrontation that is resolved peaceably by Chief Black Buffalo. Expedition stays with tribe for three more days.

October 24

Expedition encounters earthlodge villages of Mandan and Hidatsa Indians. The captains decide to build Fort Mandan across the river from the main village.

November 4

Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trapper living with the Hidatsas, is hired as an interpreter. His wife Sacagawea, a Shoshone, is instrumental as a translator and in obtaining horses from the Shoshones.

December 24

Fort Mandan is completed and the expedition moves in. Mandans provide food and other sustenance during brutally cold winter.

1805

February 11

Sacagawea gives birth to a boy, Jean Baptiste, who travels the entire length of the expedition.

April 7

Lewis and Clark send the keelboat and 12 men back downriver with maps, reports, Indian artifacts, and scientific specimens for Jefferson. The permanent party of 33 heads west.

April 29

Lewis and another hunter kill a large grizzly bear, a species previously unknown to western science.

May 29-30

Clark names the Judith River in honor of Julia (Judy) Hancock, a girl in Virginia whom he hopes to marry. Lewis classifies the White Cliffs area as another of the neverending "scenes of visionary enchantment" encountered on the journey.

June 3

The expedition reaches a fork in the river. Most of the men believe the north fork, now the Marias River, to be the continuation of the Missouri. The captains choose the south fork. Lewis later writes that, while the men are not convinced that he and Clark have made the right choice, "they were ready to follow us any wher we thought proper to direct."

June 13

Scouting ahead of the rest of the expedition, Lewis reaches the Great Falls of the Missouri. He also discovers four more waterfalls farther upstream. The expedition's 18-mile portage around the falls takes nearly a month.

July

Lewis assembles his iron-frame boat above the Great Falls, but it sinks and is abandoned. The expedition reaches the three forks of the Missouri River, and names them after Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, Secretary of State James Madison, and President Thomas Jefferson. The expedition continues to the southwest, up the Jefferson.

August 8

Sacagawea recognizes Beaverhead Rock and says they are nearing the homeland of her people, the Shoshones. Lewis and three others scout ahead.

August 12

Lewis crosses Lemhi Pass expecting to find the direct water route to the Pacific that he and Jefferson were seeking but discovers only more and more mountains ahead, creating what he called a "snowey barrier" to the Pacific.

August 15-17

Shoshones lead Lewis to their village, where he negotiates for horses. After Clark and the rest of the expedition arrive, Sacagawea meets her brother, Cameahwait, one of the Shoshone leaders. Camp Fortunate is established. On August 20, an elderly Shoshone agrees to lead the expedition across the Bitterroots to the headwaters of the Columbia.

September 11

After breaking camp south of present-day Missoula, MT, the expedition ascends into the Bitterroot Mountains, which Sergeant Patrick Gass calls "the most terrible mountains I ever beheld." A week later, with food running out, the men are forced to eat three colts and a stray horse. Clark names a nearby stream "Hungery Creek" to describe their condition.

September 22

Nearing starvation, the expedition emerges from the Bitterroots near today's Weippe, ID, where their lives are spared by a Nez Perce woman, Watkuweis. They are fed and cared for by the Nez Perce.

October 16

The expedition reaches the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers, and Clark notes a dense population of tribes.

October 31

Clark sees Beacon Rock and first sign of tidal water, indicating they are near the ocean.

November 7

Clark, who believes he can see the ocean, pens his most famous journal entry: "Ocian in view! O! the joy." The expedition is still a considerable distance from the sea, which Lewis finally reaches on the 15th. Terrible storms halt the expedition for nearly three weeks.

November 24

Members of the expedition, including York and Sacagawea, vote to set up winter quarters on the south side of the Columbia River where Clatsop Indians told them they would find plenty of elk for food and clothing.

December 8

Construction of Fort Clatsop as winter quarters begins. The fort, says Clark, is built of the "streightest and most butifullest logs." The fort is named after the local Indians.

1806

January 5

A saltmaking camp is established 15 miles southwest of Fort Clatsop. An essential dietary supplement, salt is also needed to preserve meat on the return trip.

March 23

With little ceremony, the Corps of Discovery departs Fort Clatsop and begins its long journey home.

May-June

The expedition reaches the Bitterroot Mountains but must wait for the snow to melt before crossing. For the time being, the expedition again stays with the Nez Perce, whom Lewis considers "the most hospitable, honest and sincere people that we have met with in our voyage."

July 3

Recovering some horses from the Nez Perce and buying more, the expedition successfully crosses the Bitterroots, thanks to Nez Perce guides. Once across the mountains the Corps breaks into smaller groups to explore more of the Louisiana Territory. Clark and his group travel down the Yellowstone River, while Lewis and his group take the shortcut to the Great Falls, and then head north along the Marias River.

July 25

Near present-day Billings, MT, Clark names a sandstone outcropping "Pompy's Tower" (now Pompeys Pillar) after Sacagawea's son, nicknamed Little Pomp. On the rock face Clark inscribes his own name and the date.

July 26

On their way back to the Missouri from exploring the Marias, Lewis' party encounters eight young Piegan Blackfeet. The two groups camp together warily. The following morning the Blackfeet attempt to steal the explorers' horses and guns. In the resulting fight—the only act of bloodshed during the entire expedition—two Blackfeet are killed.

August 11

Lewis is accidentally wounded in the buttocks by Pierre Cruzatte while hunting just east of present-day Williston, ND. He survives and proceeds on. The next day the entire expedition is reunited farther downstream.

August 14

The expedition reaches the Mandan villages, where Charbonneau, Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste say goodbye. She-he-ke-shote, a Mandan Indian, agrees to accompany the expedition to Washington, DC, to meet President Jefferson.

September

Speeding home with the Missouri's current, they cover up to 70 miles a day, stopping only to pay their respects at the grave of Charles Floyd, their only casualty.

September 23

After two years and four months, Lewis and Clark reach St. Louis where, according to Lewis, they "received the heartiest and most hospitable welcome from the whole village.

Fall

Upon their return to Washington, Lewis and Clark are treated as heroes. The men receive double pay and 320 acres of land as a reward; the captains get 1,600 acres. Lewis is named governor of the new Louisiana Territory, Clark is made Indian agent for the West and brigadier general of the territory's militia.

Along the Lewis and Clark Trail

CLATSOP / CHINOOK

The Clatsop Indians lived for several generations on the south side of the Columbia River near the northwest tip of what is now Oregon. They were relatives of the Chinook tribe who lived along the northern banks of the Columbia and the Pacific Coast. The Clatsops numbered about 400 and, like the Chinooks, they were wealthy and shrewd traders with few enemies. They helped the Corps of Discovery locate a site for Fort Clatsop and prepare for the winter. During their stay at the fort, the Corps' relations with both tribes were friendly.

NEZ PERCE

At their first contact with the explorers, these people named themselves with a sign language motion that resembled the action of piercing the nose. The French term nez percé means "pierced nose," but members of the tribe call themselves "Nimiipuu," meaning "the real people." After the tribe acquired horses, their trips across the Rockies to buffalo country became easier, but they still continued to fish for salmon on the Snake, Clearwater, Salmon, and Columbia rivers.

PIEGAN BLACKFEET

The Blackfeet originated on a homeland that covered today's southern Alberta, western Saskatchewan, and central Montana. Today, the tribe lives on a reservation in Montana, next to Glacier National Park and the US-Canada border.

The Blackfeet probably moved onto the plains in 1750, but traditions confirm the tribe's residency in its homeland for thousands of years. The Blackfeet are people of the plains and the buffalo.

SHOSHONE BANNOCK

The Shoshone Bannock, a division of the Northern Shoshone, live in the Rocky Mountains. They migrated to Montana and Idaho from the Great Basin of Nevada and Utah in the 1600s and became nomadic bison hunters on today's Montana plains. Sacagawea was from the Agaidaka band of the Shoshone.

TETON SIOUX

The Teton Sioux once inhabited a vast territory in the northern prairies and plains in today's North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska. They are one of three groups of tribal people sharing a closely related language who call themselves Nakota, Dakota, and Lakota.

The name "Teton" comes from the native word tetonwan that means "dwellers of the prairie" and aptly describes their original territory. They have lived in the prairies of North America for hundreds of years.

MANDAN / HIDATSA

Long before Europeans arrived on the plains, the Mandans and their Hidatsa neighbors lived in fortified earthlodge villages along the Missouri River. These agricultural tribes traded their farm produce and Knife River flint to other tribes and later were leaders in developing the trade with Hudson's Bay and American Fur Company traders.

The men of these tribes honed their hunting skills and formed hunting parties in the summer to pursue the buffalo. Women grew corn, squash, sunflowers, and beans in plantings along riverbanks. Men and women took part in religious ceremonies held throughout the year.

Things to Know About the Lewis and Clark Trail

(click for larger map) |

In 1978 Congress established the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail as part of the National Trails System. The 3,700-mile-long trail begins in Hartford, Illinois, and passes through Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

The trail traces the explorers' route as closely as possible given the modern landscape. Today you can follow in the footsteps—or close to them—of Lewis and Clark, exploring the route they traveled and experiencing the adventure of the Corps of Discovery. Travel by car, bus, or train, boat, canoe, or kayak, on foot or bicycle. Interpretive signs, exhibits, visitor centers, and living history programs are found along the way, helping you learn about the trail and the epic journey it commemorates.

The National Park Service administers the trail through partnerships with federal, state, and local agencies; tribal nations; nonprofit organizations; and private landowners. It is especially important to respect tribal land regulations and the rights of private landowners. If an area is not open to visitors, you must obtain permission to enter the property.

Do not disturb these lands by littering or removing items from sites. Natural and cultural features of the trail are protected by law; please do not disturb them.

As you follow the trail route, look for signs with the Lewis and Clark image. A rectangular sign designates a highway that is a Lewis and Clark Auto Tour Route. The designated motor routes—for bus or car—follow the historic trail as closely as possible.

The Trails & Rails Program, sponsored by Amtrak and the National Park Service, allows train passengers to learn about the natural, cultural, and historical features—including sites associated with Lewis and Clark—while traveling. For more about Trails & Rails, visit www.amtrak.com.

Recreational opportunities abound. Information on hiking, biking, and horseback trails is available from the local, state, and federal agencies that administer them.

If you plan to travel the water route by boat, canoe, or kayak, please be aware that long portions of the rivers Lewis and Clark traveled are now impounded by dams. The dams on the Snake and Columbia rivers have locks; Missouri River dams do not. Commercial boat trips are available on some segments.

Six different water trails cover some 1,373 miles of the Lewis and Clark water route:

Missouri River Water Trail

missouririverwatertrail.org

Missouri National Recreational River

Water Trail www.nps.gov/mnrr

Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument

www.blm.gov/mt/st/en/fo/umrbnm/interpcenter.html

Jefferson River Canoe Trail

www.jeffersonriver.org

Northwest Discovery Water Trail

www.ndwt.org

Lower Columbia River Water Trail

www.estuarypartnership.org/explore

The Lewis and Clark Trust serves as the friends group for the national historic trail. The Trust is dedicated to telling the story and preserving the trail from coast to coast. Learn more at www.lewisandclarktrust.org.

The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation is a nonprofit national organization preserving the heritage of the Lewis and Clark expedition. The foundation publishes the quarterly magazine We Proceeded On and meets each year at one of the Lewis and Clark sites. Visit www.lewisandclark.org.

The headquarters of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail is located on the Omaha riverfront in the NP5 Midwest Regional Office. A visitor center operates year-round.

To take a more in-depth look at the Trail's geography, visit the Interactive Trail Atlas at www.lewisandclarktrailmap.com.

Source: NPS Brochure (2016)

|

Establishment Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail — March 21, 1978 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Pirogue by any other Name...A Backward Glance at the Corps of Discovery's Watercraft (Allen "Doc" Wesselius, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 21 No. 1, Spring 2007; ©Washington State Historical Society)

A Windfall for Educators: The Lewis & Clark Bicentennial (Robert C. Carriker, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 18 No. 1, Spring 2004; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Adventures in Ichthyology: Pacific Northwest Fish of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Dennis D. Dauble, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 19 No. 3, Fall 2005; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Annual Reports: 2016 • 2017 • 2018 • 2019 • 2020 • 2021 • 2022 • 2023 • 2024

Archaeological Sites of the Lewis & Clark Expedition Through Oregon and Washington 1805-1806 (Oregon Archaeological Society, 2004)

Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Lewis and Clark National Historic Park, Oregon and Washington NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR-2007/055 (Terrie Klinger, Rachel M. Gregg, Jessi Kershner, Jill Coyle and David Fluharty, September 2007)

Beginnings & Endings: Lewis and Clark After the Expedition (Landon Y. Jones, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 18 No. 3, Fall 2004; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Captains West: Lewis & Clark in the Vanguard of Army Exploration (James P. Ronda, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 18 No. 1, Spring 2004; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Commemoration and Collaboration: An Administrative History of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail (Jackie Gonzales and Emily Greenwald, 2018)

Comprehensive Plan for Management and Use, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail (January 1982)

Continuing the Legacy of Lewis and Clark USGS Fact Sheet (undated)

Following in Their Footsteps: Creating the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail (Wallace G. Lewis, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 16 No. 2, Summer 2002; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Foundation Document, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, IL-MO-KS-NE-IA-SD-ND-MT-ID-WA-OR (September 2012)

Foundation Document Overview, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, IL-MO-KS-NE-IA-SD-ND-MT-ID-WA-OR (January 2013)

Geophysical Investigations of Four Suspected Pioneer Grave Locations Along the Oregon and California National Historic Trails, Marshall and Pottawatomie Counties, Kansas Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report Series No. 90 (Steven L. DeVore and Robert K. Nickel, 2003)

Grouse of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Michael A. Schroeder, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 17 No. 4, Winter 2003-04; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Half Starved: Lewis and Clark on the Lolo Trail (David L. Nicandri, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 24 No. 2, Summer 2010; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Heartily Tired of the National Hug: Why Sacagawea Deserves a Day Off (Stephenie Ambrose Tubbs, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 20 No. 4, Winter 2006-07; ©Washington State Historical Society)

High Potential Historic Sites: An Addendum to the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Comprehensive Plan for Management and Use (February 2018)

Hunting for Empire: Lewis and Clark Claim a Continent for Science (Daniel Herman, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 17 No. 2, Summer 2003; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Illustrating Lewis & Clark: Images of the West in 19th-Century Lewis and Clark Literature (Kerry R. Oman, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 20 No. 3, Fall 2006; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Information and Maps Excerpted from Comprehensive Plan for Management and Use, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail (January 1982)

Junior Web Ranger, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Knowing Your "Place": Lewis & Clark and the Invention of American Regionalism (James P. Ronda, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 16 No. 1, Spring 2002; ©Washington State Historical Society)

John Ordway: Lewis and Clark's Indispensable First Sergeant (Thomas D. Morgan, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 19 No. 4, Winter 2005-06; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Lewis and Clark Trail: Final Report to the President and to the Congress, The Lewis and Clark Trail Commission (October 1969)

Lewis & Clark's Indian Presents: The Evolving and Misleading Documentary Record of the Expedition Inventory (Kenneth Karsmizki, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 16 No. 4, Winter 2002-03; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Lewis & Clark's Water Route to the Northwest: The Exploration That Finally Laid to Rest the Myth of a Northwest Passage (Merle Wells, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 8 No. 4, Winter 1994/95; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Long Iron: The Black Powder Arms of Lewis & Clark (Mark Van Rhyn, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 18 No. 3, Fall 2004; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail (September 2018)

Meriwether Lewis's Little Red Book: A Pacific Northwest Legacy (John C. Jackson, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 25 No. 3, Fall 2011; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Mountains of Eternal Snow: Lewis and Clark and the Cascade Range Volcanoes (Allen "Doc" Wesselius, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 20 No. 2, Summer 2006; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Museum Management Plan, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (Robert Applegate, Jonathan Bayless, Barbar Beroza, Blair Davenport and Deborah Wood, August 2005)

Nor Any Drop to Drink: The Search for Water on the Journey West (Jacqueline Williams, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 7 No. 2, Summer 1993; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Old Rivet: The Surviving Member of the Corps of Discovery in the Northwest (John C. Jackson, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 18 No. 2, Summer 2004; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Park Newspaper (The Trail Companion)

2009: Fall

2012: February • May • August • December

2013: February • June • August • December

2014: February • May • August • November

2015: February • June • August • November

Provision Camp: The Lewis & Clark Expedition, March 31 to April 6, 1806 (Roger Daniels, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 16 No. 3, Fall 2002; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Scientific Explorers: A Review of Literature on Lewis and Clark's Ethnography, Botany, and Zoology (Jay H. Buckley and Julie A. Harris, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 20 No. 1, Spring 2006; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Searching for Point Lewis: Piecing Together the Location of a Lost Landmark (Allen "Doc" Wesselius, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 18 No. 4, Winter 2004-05; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Sold Our Canoes for a Few Strands of Beads: The Lewis & Clark Canoes on the Columbia River (Robert and Barbara Danielson, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 19 No. 1, Spring 2005; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The Diplomacy of Lewis and Clark among the Teton Sioux, 1804-1807 (Harry H. Anderson, extract from South Dakota History, Vol. 35 No. 1, Spring 2005, ©South Dakota Historical Society)

The Lasting Legacy: The Lewis and Clark Place Names of the Pacific Northwest—Part I (Allen "Doc" Wesselius, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 15 No. 1, Spring 2001; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The Lasting Legacy: The Lewis and Clark Place Names of the Pacific Northwest—Part II (Allen "Doc" Wesselius, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 15 No. 2, Summer 2001; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The Lasting Legacy: The Lewis and Clark Place Names of the Pacific Northwest—Part III (Allen "Doc" Wesselius, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 15 No. 3, Fall 2001; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The Lasting Legacy: The Lewis and Clark Place Names of the Pacific Northwest—Part IV (Allen "Doc" Wesselius, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 15 No. 4, Winter 2001-02; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The Legacy of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Michelle D. Bussard, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 12 No. 1, Spring 1998; ©Washington State Historical Society)

The Lewis and Clark Trail: A Proposal for Development (1965)

The Lewis and Clark Trail: A Proposed National Historic Trail (April 1977)

The Lewis and Clark Trail: Final Report to the President and to the Congress (October 1969)

THE VOTE: "Station Camp," Washington (Dayton Duncan, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 15 No. 1, Spring 2001; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Trail Program News: October 2, 2006 • February 5, 2007 • June 8, 2007 • September 25, 2007

Twisted Hair, Tetoharsky, and the Origin of the New Sacagawea Myth (David L. Nicandri, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 19 No. 2, Summer 2005; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Ways of Knowing—Thoughts on Beyond Lewis & Clark: The Armey Explores the West (Allyson Purpura, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 17 No. 4, Winter 2003-04; ©Washington State Historical Society)

What the Lewis and Clark Expedition Means to America (Dayton Duncan, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 11 No. 4, Winter 1997-98; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Why Lewis and Clark Matter: History, Landscape and Regional Identity (Cindy Ott, extract from Historical Geography, Vol 35, 2007, ©Geoscience Publications)

lecl/index.htm

Last Updated: 22-Mar-2025