|

CASUALTIES OF WAR:

The Effects of the Battle of Gettysburg Upon the Men and Families of the 69th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

by D. SCOTT HARTWIG

There were 459 infantry and cavalry regiments and

132 artillery batteries that participated in the Battle of Gettysburg,

representing over 160,000 Union and Confederate soldiers. Of this number

incomplete statistics tell us that in three days 7,608 men were killed,

26,856 were wounded, and 10,800 were missing or captured; over 45,000

people. Actual losses were probably as high as 51,000. The numbers are

so large that they are incomprehensible. No one can fathom the shock

wave of suffering, grief, pain and misery they sent through the north

and south. I have often wondered how the casualties and their families

were affected by this three-day battle. What did it mean to them? How

did it affect them? How were their lives changed? How did they cope with

the loss of life, of limbs, of vigorous men returned home with health

permanently shattered? For the casualties and their families the

three-day Battle of Gettysburg marked the beginning of a hard, and often

harsh, journey. It is not a happy story, but there is heroism

nonetheless. Not the heroism that causes a man to stand against an

onrush of enemy soldiers, but of people who struggle against the fates

of life when all of the odds seem against them. Sometimes they prevail.

More often they do not, but that does not diminish the effort.

|

|

Officers of the 69th Pennsylvania in May 1865. Among them, Col.

William Davis (seated center), Major Patrick Tinen (seated left), and

Surgeon Burmeister (standing, with sash). (Library

of Congress)

|

To tell the story of what 45,000 or 51,000

casualties means is impossible. I have selected to tell only a sliver of

it; to examine the impact of the battle upon a single regiment of

infantry and their families; the 69th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

By greatly narrowing the focus we can render the incomprehensible into

something the human mind can grasp. By learning of the battle's effect

upon 20 or 30 casualties and their families, we can establish a

foundation upon which we can start to form the mental adjustments

necessary to even begin to comprehend what 200, or 2,000, or 20,000 or

51,000 casualties really means.

The July 2 morning report of the 69th Pennsylvania

Volunteer Infantry, recorded that there were 26 officers and 258

enlisted men present for duty in the regiment. This represented less

than one-half of one per cent of the total present for duty strength of

the Army of the Potomac. They were but a cog in a giant machine of war;

so small that they could be swallowed up by the voracious jaws of battle

and hardly noticed. The regiment reached the battlefield on the night of

July 1, after a tiring 14-mile march from Taneytown, Maryland. They,

and the rest of Major General Winfield Scott Hancock's 2nd Army Corps

stirred early on July 2 and moved into position along Cemetery Ridge, in

the center of the Union army's line of battle. The 69th belonged to the

2nd Brigade of the 2nd Division, otherwise known as the Philadelphia

Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Alexander Webb, and

consisting of the 69th, 71st, 72nd and 106th Pennsylvania.

Shortly after sunrise Webb's Brigade took position on

the gentle western slope of Cemetery Ridge behind a stone wall and near

a clump of trees and bushes that had taken root in the thin, rocky soil.

One day this area would be known as "The Angle" and "The High Water

Mark," but on July 2, 1863, it was simply a stone wall and clump of

trees and bushes that Webb's men needed to convert into a defensive

position in the event they were attacked. Because of the density of

troops on Cemetery Ridge, Webb had room for only one regiment on the

front line. He selected Colonel Dennis O'Kane's 69th Pennsylvania, a

largely Irish unit with a good combat record and reputation for

discipline and steadiness. [1]

At about 6:30 p.m. Cemetery Ridge was assailed by

the Georgia brigade of Brigadier General Ambrose R. Wright. The

Georgians struck the ridge slightly to the left of the 69th's position,

but close enough that O'Kane's men became heavily engaged in the effort

to fight off the attack. "Our men fought with the bravery and coolness

of veterans," reported Captain William Davis, of Company K. The 69th

and other regiments of their brigade, and the brigade of Colonel Norman

Hall, prevailed in the hard fought battle and Wright was forced to

withdraw. The 69th reported 11 killed and 17 wounded in the action,

almost ten per cent of the regiment, although actual losses were

probably only 6 killed and 12 wounded. Among the wounded was 35-year old

Lieutenant Colonel Martin Tschudy, who was struck on the side of the

head. Tschudy did not consider the wound serious enough to leave the

field and he remained with the regiment. [2]

|

|

Col. Dennis O'Kane (left), Lt. Col. Martin Tschudy (right) (McDennott's History of the 69th Pennsylvania.)

|

Until 1 p.m., July 3 proved largely uneventful for

the regiment, excepting some early morning artillery exchanges and

sharp skirmishing in the contested ground between Cemetery Ridge and

Seminary Ridge. At 1 p.m. the Confederate artillery opened an intense

bombardment of the Union lines intended to smash up the Union center

and to pave the way for a massive infantry assault. For nearly two

hours the 69th was subjected to artillery fire. Then, at about 3 p.m.

over 12,000 Confederate infantry moved forward to attack Cemetery Ridge.

Despite intense Union artillery fire, the Confederate infantry succeeded

in crossing the Emmitsburg Road and storming up the slope of Cemetery

Ridge. The Union infantry poured a murderous fire into the Southern

ranks, checking them at some points, but allowing them to continue to

press forward elsewhere. One point where they did so was on the front of

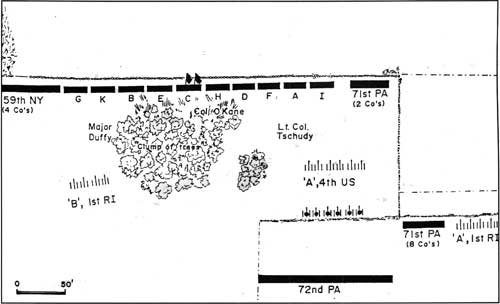

the 69th. On the right of the regiment, a space of about 40 feet

extending to the angle was filled by part of the 71st Pennsylvania [see

map insert]. These men were driven back, and elements of Brigadier

General Richard B. Garnett's Brigade of Pickett's Division seized this

section of the wall. Garnett's men were soon reinforced by parts of

Brigadier General Lewis B. Armistead's Brigade. [3]

|

|

The Philadelphia Brigade at "The Angle" before Pickett's Charge

(Gettysburg Magazine - Morningside

Press

|

|

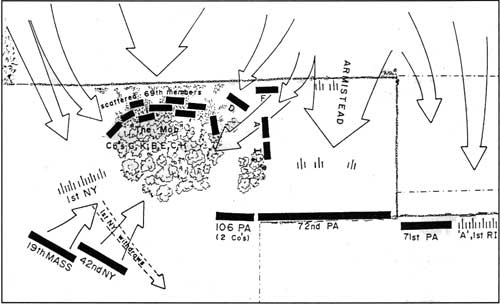

|

Fighting at the "The Angle" during Pickett's Charge

(Gettysburg Magazine - Morningside

Press

|

While trouble brewed on the right flank of the 69th,

the front and left of the regiment were engaged with elements of both

Garnett's and Annistead's Brigades in a tremendous firefight. The left

rear of the 69th was supported by five guns of Captain Andrew Cowan's

1st New York Independent Battery. Cowan's three-inch rifles were dealing

out great destruction to the Confederates with blasts of canister, but

one or more of his guns evidently had been depressed too low and some of

its canister killed and wounded several men in companies G and K on the

left of the 69th. Earlier in the engagement a premature blast of

canister from one of Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing's three-inch rifles

killed two men in Company I. Under intense fire from both friend and foe

the pressure upon the regiment mounted. Then, a surge of Confederates,

led by Annistead, suddenly poured over the stone wall at the angle, past

the right flank of the 69th. The three right companies, I, A, and F,

were ordered to change front to the north to protect the regiment's

flank. I and A were able to execute this exceptionally difficult movement,

but the commander of Company F, Captain George Thompson, was shot

in the head and killed and his company remained at the

wall. [4]

There were still many Confederates behind the stone

wall at the angle, and when they observed I and A companies fall back

to fight Armistead and his followers, they poured over the wall, heading

straight for a gap that developed between A and F companies. Along the

way they scooped up 31-year old Sergeant Edward Bushel, of A Company as

a prisoner. The rush of Virginians then descended upon the exposed

flank and rear of Company F. In a matter of moments the company lost 22

men, nearly its entire strength. Forty-year old Neil McCafferty was

killed, eleven men were wounded, both lieutenants and eleven enlisted

men were captured. The next company in line, Captain Patrick Tinen's

Company D, "were obliged to turn upon the enemy to their flank and

rear." Anthony McDermott, of Company I, wrote that "many of the enemy

were here mingled with our own men," and that "the fighting here at

close quarters was more desperate than at any other part of our line."

Lieutenant Colonel Tschudy was shot through the bladder in this melee

and dropped mortally wounded. Tinen's company lost 8 killed, 7 wounded,

and 2 captured, a large percentage of the company, but their hand-to-hand

conflict with Garnett's and Armistead's Virginians, in the

opinion of McDermott, "saved the remainder of the regiment from being

enveloped, and possible capture." [5]

Meanwhile, on the left of the regiment, the confusion

caused by the fire in rear from Cowan, and the Confederate attack upon

the 69th's right, allowed men of Garnett's Brigade to press right up to

the stone wall, where men of Company G, K, and B were sheltered. John

Buckley, a member of Company K, recalled how some Confederates

"actually stepped over them," before they were shot down. The center

companies, E, C, and H, and some men from the left companies, pulled

back from the wall because, "the fear of capture had made them cautious

about sticking close to the wall." Joseph McKeever, of Company E,

testified that, "we all fell back just as they (Confederates) were coming

in to the inside of the trees, and they made a rally, and then they were

coming in all around, but how they fired without killing all of our

men I do not know." It was a terrifying, bloody close-quarter

engagement that no one in the center and left of the regiment could ever

recall with much precision. Joseph McKeever possibly summarized it best

when he responded to a question on the nature of the fight at that

point, "it was quite a mob. Everybody was doing the best he

could." [6]

Help soon came to succor the beleaguered 69th. Union

regiments to their left and right rallied and poured a destructive fire

into the ranks of the Confederates engaged with the Pennsylvanians.

Although it would be difficult to prove, it is very likely that some of

this friendly fire struck men in the 69th as well as their Confederate

opponents. Nevertheless, enough bullets were fired in the right

direction to cause Confederate resistance to collapse, and for their

survivors to surrender or run a gauntlet of fire to reach friendly

lines. The Confederate infantry assault had commenced around 3 p.m.

Approximately one hour later it was over. The infantry fighting -

perhaps 200 yards and under - had consumed no more than 20 to 25

minutes. Nearly all of the 69th's July 3 casualties occurred in this

time span. The exact number suffered during the two-hour cannonade is

unknown, but were few in number. In his report of the battle, submitted

on July 12, 1863, Captain William Davis, who assumed command of the

regiment after all of the field officers were killed or wounded,

reported that his regiment had lost 32 killed, 71 wounded, and 18

missing in action on July 3. But in the immediate aftermath of a battle

there are always mistakes made and Davis's casualty report was not

entirely accurate. The best (and even the best can often be questioned)

evidence gives losses for July 3 at 34 killed, 68 wounded, and 17

missing in action. All told, in two day's of battle, there were 40 men

killed outright or dead from their wounds within a day or two, 80

wounded, 16 of them mortally, and 17 captured. One hundred thirty seven

people - all casualties of war in a relatively brief period of intense

violence on the slopes of Cemetery Ridge. How those few minutes affected

these men and their families for the rest of their lives is our story.

[7]

The fighting on the late afternoon of July 2 fell

heavily upon 1st Lieutenant John McIlvain's Company B. The 30-year old

Irish-born McIlvain himself was wounded, shot through the right arm

near the shoulder. But he recovered from his wound and remained with the

regiment until he was dismissed from the army on February 10, 1865. One

of the company's sergeants was Nicholas Farrell. Farrell was 29 years

old at Gettysburg. His birthplace, like many in the regiment, was

Ireland, in County Louth. He found work in this country as a laborer, the

most common occupation in the 69th Pennsylvania, before enlisting in the

army on August 24, 1861. On December 13, 1862, at the Battle of

Fredericksburg, Farrell, then a corporal, received a gunshot wound in

his left leg about four inches above the ankle. It splintered the bone

and Farrell spent nearly six months in different hospitals before he

returned to the regiment in May. He was promoted to sergeant on May 1,

and somehow his leg endured the hard marching of the Gettysburg

Campaign. Then, on the evening of July 2, one of Ambrose Wright's

Georgians, carrying a smoothbore musket loaded with buck and ball, fired

and hit Farrell with three buckshot just under his right knee. The

sergeant was evacuated from the field and transported to Satterlee

General Hospital in West Philadelphia on July 10, 1863. He recovered

quickly from his wound and returned to duty on August 6, 1863. Late that

fall he re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer and served to the end of the

war. [8]

Following the war, Farrell married Rosenna Fortescue

at St. James Catholic Church in Newark, New Jersey, where he had taken

up residence. We can only wonder what Farrell and his wife Rosenna hoped

for in the country he had adopted as his home and had fought to

preserve. The marriage produced three daughters. Farrell continued to

work as a laborer, but the wounds to his legs likely troubled him

greatly in such work. On December 22, 1873, he applied for a government

pension for wounds received in the service. The Pension Office approved

his application and he began receiving $4 a month. Farrell also drank

heavily, and the drinking, manual labor, and war wounds took their toll

on his body. By 1890 a physician reported that his body was emaciated,

"skin sallow and clammy," and that he had extreme varicose veins,

enlarged four times their normal size. Three years later Farrell died,

at age 59. His wife preceded him in death by one month. Their three

daughters, aged 19, 16, and 13 survived them. The two oldest fended for

themselves. Theresa, the youngest, had Teresa Duff appointed as her

guardian by the state. The family had dissolved. For Farrell, the

Gettysburg wound, while troubling, did not affect him as severely as the

one received at Fredericksburg. It was the cumulative effect of wounds

and exposure during his four years of military service that slowly

destroyed a once vigorous man. [9]

Company K, on the left of Company B, lost only 1

killed and 1 wounded in the action on July 2. The wounded man was Henry

W. Murray, a 21-year old Philadelphia bookbinder. A bullet struck

Murray in the right eye and destroyed the sight in both eyes. John

Buckley, a friend of Murray's, led him to the rear for medical

attention. Twenty-three years later Buckley recalled that Murray was

"begging me to put an end to that existence which he thought would be no

longer endurable." Buckley, of course did not, and Murray spent the

remaining twelve months of his military service in hospitals and was

discharged from the army in the summer of 1864 at the expiration of his

enlistment. He received a pension from the government for his terrible

wound beginning in November, 1864.

Somehow, Murray found a reason to continue to exist,

although, in addition to blinding him, his wound had done serious nerve

damage. Perhaps it was Hannah W. James who made the difference in his

life, and gave him the will to go on. On June 15, 1867, they were

married in Philadelphia and eventually moved to Cleveland, Ohio. How

they supported themselves is unknown, though Hannah likely found some

form of employment. They made do in some way, while Henry's condition

continued to worsen. By 1874, in a statement to the Pension Office,

Murray related that he was so "permanently and totally disabled as to

require the regular presence, aid and attendance of another person to

prepare his food for him, to conduct him from place to place and to

perform such other duties as personal needs constantly require." Murray

left evidence of his struggle to preserve some shred of his dignity and

person on this statement - he signed it. The signature is shaky and not

made with a firm hand, but it is clear that Henry Murray refused to give

up despite the humiliating existence his Gettysburg wound had reduced

him to. [10]

Murray lost his battle on December 10, 1884. At age

42 he died of what was diagnosed as Bright's disease of the kidney's,

which the physician believed was brought about by the nerve damage

resulting from the gunshot wound to his head. His wife Hannah remained

in Cleveland, where she passed away in 1916.

Company H, immediately to the right of color company

C, suffered only one casualty in the July 2 action. Twenty-one year old

2nd Lieutenant Charles F. Kelly was killed by a shell fragment that

penetrated his brain. Kelly had enlisted in the regiment on August 15,

1861. His brother, Thomas Kelly, recruited the company at 1140 Market

Street in Philadelphia between August 15 and September 2. This was an

exciting time, and young Charles' enthusiasm is evident from the fact

that he enlisted the first day recruiting commenced. The Kelly brothers

had lost their father in 1855, and since then they had been the sole

financial support of their mother, Susan Kelly.

After their enlistment in the army, they continued

to send regular payments to their mother. As a captain, Thomas earned

$60.00 a month, and Charles, who was a sergeant, made $17.00. Between

the two of them, they were probably able to keep their mother

comfortable. On September 17, 1862, at the Battle of Antietam, Thomas

received a wound that put him out of action for several months. During

his absence a 2nd Lieutenant vacancy developed when Owen Sheridan was

dismissed from the army May 15, 1863. Whether or not his brother pulled

strings for him is unknown, but probable. Whatever occurred, Charles

Kelly was selected to fill the vacancy in Company H, and on June 5,

1863, he was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant. This gave Kelly a pay raise

of $28.00 a month, as the pay of a 2nd Lieutenant was $45.00 a month.

But Charles made only one muster for pay as a commissioned officer, on

June 30 at Uniontown, Maryland. Two days later he lay dead on the

battlefield at Gettysburg. [11]

Susan Kelly, unlike many families of men in the 69th,

was able to afford to have her son's body removed from the battlefield

and reburied in Philadelphia, at the Cathedral Cemetery. She applied

for a pension in September, 1863, and was awarded the standard $15.00

the government allotted for a dead 2nd Lieutenant. Meanwhile, her

oldest son, Thomas, had recovered from his wound and returned to command

of his company, leading it through the fierce fighting in the

Wilderness on May 5 and 6, 1864, then on to Spotsylvania Court House. On

May 12, in some of the most terrible fighting of the war, at what became

known as "The Bloody Angle," Thomas was mortally wounded. He died on May

18. Susan Kelly had given up both sons to the war. Before he died,

Thomas asked Father Thomas Willett, a chaplain with the 69th New York

Infantry who took Kelly's confession, to write his mother. Willett was a

busy man that spring of 1864, but he made time to send Thomas's last

wishes to Susan Kelly on June 9.

"Tell my mother I have done all I could to take

care of them as long as I could. Now I can't do it anymore, I have to

submit to the will of God. I hope my pension and that of my Brother will

be enough to support my mother, and I beg of my Brother-in-law Frank to

see that she may not be in want. . ."

In order to save expenses he had also expressed a

wish that his body should remain where he fell, but I understood from

Mr. McManus of Baltimore whom I saw yesterday at the white house, that

he subsequently consented to be taken home.

May Almighty god come to your assistance and

console you under the present trying and painful

circumstances. [12]

|

|

The document that Henry Murray signed. (click on

image for a PDF version)

|

It is clear from Thomas's last statement and the

pension file of Charles Kelly, that Susan Kelly's financial resources

were meager. Between the $15.00 she collected as a result of Charles'

death, and the $25.00 a month Thomas had sent her, she managed to exist.

With Thomas dead, her income had been reduced by sixty per cent. As much

as she probably grieved her son's death, the harsh financial

implications Thomas's death meant for a middle-aged illiterate woman

were frightening. Pension laws made it unlawful for a widow or parents

to collect a pension for more than one son lost in the service, but

Susan knew that the pension for a captain was $20.00, $5.00 more than

she drew for her son Charles. So, sometime in 1867, she made an

application to draw her pension based upon Thomas' rank as captain,

rather than upon Charles'. As was frequently the case, the bureaucracy

of the Pension Office did not react to change well. Susan Kelly's

application was denied; she already drew $15.00 a month, and apparently

she did not make a convincing argument, or omitted to mention that her

son Thomas had been supporting her. Her attorneys appealed the ruling,

and four months later Susan Kelly's pension was adjusted to $20.00 a

month. It was a bittersweet victory, for no amount of money the

government could offer would ever assuage the grief and emptiness Susan

Kelly knew after Gettysburg and Spotsylvania [13].

The battle action of July 2 paled in comparison to

the fire-storm the regiment was subjected to on July 3; first the

terrible cannonade, then the infantry attack. Twenty-four year old 2nd

Lieutenant Edward D. Harmon was one of two officers in Company I, on

the extreme right of the regiment. Their captain, Michael Duffy, had

been killed in the fighting on the evening of July 2. Harmon had

enlisted in the 69th as a private, but demonstrated leadership potential

and was promoted to sergeant major of Company I. Then, on May 1, 1863,

he was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant. Before the war he had been a

type-founder, an occupation that entailed the design and production of

metal printing type for hand composition. Harmon's hands were the means

with which he earned his living.

When Armistead led the Confederate advance over the

stone wall at the angle, it became the duty of Harmon and the other

officers and non-commissioned officers to withdraw I and A companies

from their position at the wall to confront the threat to the regiment's

flank. This was perilous duty, for it required everyone to expose

himself to Confederate fire in order to change positions. At some point

in executing this change of front, a Confederate minnie ball struck the

back of Harmon's left hand, passing completely through it. The muscles

of the hand were severed, causing the fingers to contract and rendering

Harmon's hand useless. Regimental Surgeon F. F. Burmeister dressed the

lieutenant's wound on the battlefield, then had him transferred to a

general hospital at Baltimore. From this hospital Harmon received

permission to return to Philadelphia and have a family physician attend

to his wound. In that era, however, the damage to the hand could not be

repaired with surgery. Precisely what Harmon did for the next few months

is unknown, but he did not return to his regiment. On February 25,

1864, he was discharged from the army "on account of physical disability

and absence without leave," because he had failed to file the necessary

surgeon's certificate for disability with the adjutant general's office.

As in modern times, the Civil War army had an abundance of red tape.

[14]

We do not know how Harmon reacted to his wound. Was

he bitter over the bad luck that a man who earned his living with his

hands had now lost the use of one of them? Or did he accept his wound

philosophically, as part of the danger he acknowledged as being an

infantry officer? Whatever it was, in February, 1864, he was a man who

could no longer earn his living as a type-founder. His activities for

the next three years are unknown, although he probably did some form of

manual labor to earn a living. On March 26, 1867, he applied for a

pension, citing his wound and that "he has been totally unable to earn

his subsistence by manual labor." His application was approved and

Harmon commenced receiving $15.00 a month. But six years later the

Adjutant General's Office examined Harmon's record and concluded that he

had overdrawn his pay for the period from September 25, 1863, until his

discharge on February 25, 1864. Harmon owed the government $513.84. He

had no means to pay it, except his pension. On April 16, 1873, he wrote

the commissioner of pensions and authorized him to direct his pension

payments to the Adjutant General's Office until the amount due was paid

up, about three years. [15]

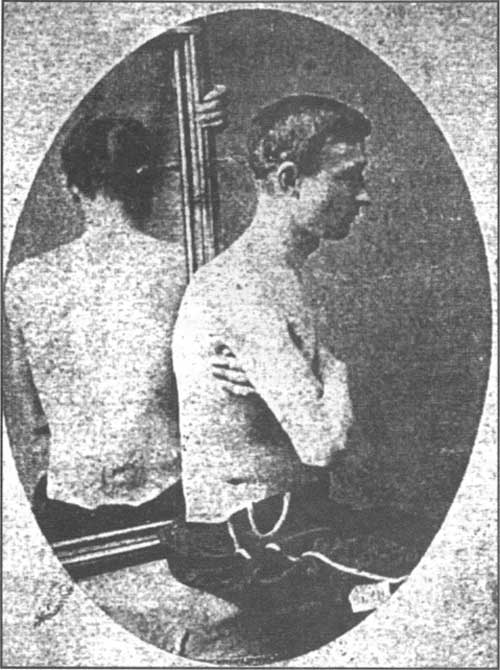

|

|

Lieutenant Edward Harmon's hand.

|

On April 27, 1887, Harmon applied for an increase to

his pension which was denied. It appears he tried again in April, 1890,

for he was examined by a physician on April 22. As part of the

examination, Harmon laid his gnarled hand down on the surgeon's chart

and the doctor traced its outline to record the effect of his Gettysburg

wound. If he did apply for an increase it was again denied. He submitted

another application in April, 1896. How he fared is unknown, for his

pension file is not complete. Nevertheless, despite a crippling wound

that robbed him of his occupation, and army red-tape that dogged him

into the 1870's, Harmon somehow made do and lived a long

life. [16]

Among the other members of Company I who attempted

the perilous withdrawal from the wall and change of front was 20-year

old Thomas C. Diver. Before the war he had worked as a printer, earning

$4-S a week, decent pay among the privates of this regiment. He lived

with his mother, Jane Diver, a widow who had lost her husband in 1840.

Thomas was his mother's sole means of support. When he enlisted in the

army on August 19, 1861, he dutifully continued to send his mother

nearly all of his pay in regular installments. Although Jane Diver

could neither read nor write, she had seen to it that her son received

an education. Thomas was a bright and sensitive young man who wrote his

mother regularly from the front. His letters show a clear hand, an

observant eye, and a deep concern for his mother. After the Battle of Fair

Oaks, May 31 - June 1, 1862, he wrote his mother, "Dear Mother do not

worry about me for I will send you word in a letter directly after a

battle. I am very easy about the danger for I trust in

God!" [17]

A relative of the Diver family apparently dictated

letters for Jane Diver to her son on a regular basis, for on February

22, 1862, he wrote back to her, "I am sorry to hear that you are so

lonely at home and I wish that I could come to cheer you up." Thomas

wrote that he had considered taking "French leave" to come home, and had

even purchased some civilian clothing from the sutler to aid his

escape. "But on further consideration I changed my mind," he wrote. Two

months later, on the eve of the Battle of Chancellorsville, he wrote his

mother that part of the army had crossed the Rhappahannock River, "I

hope they are victorious poor fellows. There will be a great many of

them fall and a great many poor Mothers hearts broken." Later in the

same letter he ruminated on the war and his enlistment, "Dear Mother I

think that this war will not last longer than this summer and then even

if it does I have got only 15 months to stay and that will slide around

quicker than the 21 months that I have been away." [18]

For Thomas the war would end that summer. At some

point during the Confederate surge to the angle, or during the

withdrawal of Company I from the wall, a Confederate bullet struck him

in the head and killed him. His comrades buried him on the battlefield.

Later he was removed to the Evergreen Cemetery. We do not know how Jane

Diver reacted to the news of her son's death, but if his letters are an

indication, it must have been a terrible blow. At 44 years of age she

was alone, and probably frightened. She had relatives in the area who,

according to Thomas's letters, provided her company. But with her son

dead her sole means of financial support was her job at the United

States Arsenal at Philadelphia. For reasons unexplained, she waited more

than a year before applying for a pension. On August 18, 1864,

accompanied by two friends, Rose Maginn and Patrick F. Foy, who

testified on her behalf, she filed her application. The application was

approved and she received $12 a month for her dead son. She collected

this pension for the next 29 years until her death at age 73. At some

point, apparently, she found the means to bring her son's body home, for

he is no longer buried at Gettysburg. [19]

|

|

George Deichler in 1865 displaying wound he received at 2nd Hatcher's

Run. (Deichler's Pension file - National

Archives)

|

Among the non-commissioned officers who supervised

the movement of Company I from the wall was Corporal George P. Deichler,

a 24-year old machinist from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he lived

with his father, Philip. During the action, a Virginian's bullet hit

Deichler in the left groin. This serious and very painful wound laid the

corporal up for many months. He recovered though, and returned to his

regiment only to be wounded again at Ream's Station, on August 25, 1864,

where a shell fragment struck him in the head and a minnie ball hit his

knee. Though he spent nearly six months in convalescence, Deichler was

tough, and he returned to the regiment in March, 1865, and was promoted

to 1st Lieutenant. Nine days after his promotion, on March 25,

1865, at the 2nd Battle of Hatcher's Run, a Confederate bullet hit

Deichler in the lower part of the stomach and blew a hole in his back.

Deicheler's captain, Joseph Garrett, wrote of the wound; "I considered

it serious as the fluids and other matter was coming out from the

Bowels." This, Deichler's fourth wound, finished his soldiering, though

somehow his iron constitution pulled him through and he survived it. He

received his discharge and was pensioned at $17 a month beginning August

10, 1865. [20]

Sometime after his discharge Deichler moved to

Indianapolis. He met Annie E. McDougal there. She had recently divorced

her first husband, and on July 26, 1875, John G. Smith, a Minister of

the Gospel, married Annie and George. But the marriage that began with

high hopes unraveled over the next six years. George's Gettysburg wound

in the groin may have had something to do with the problems the couple

experienced. He also drank heavily, probably to ease the constant pain

that assailed his body from his four wounds. To make ends meet, Annie

had to take in boarders, and find whatever other work she could. It was

not enough. On June 4, 1881, Deichler left his wife and returned to

Lancaster to live with his father. There was no divorce, Deichler simply

left. [21]

One year later, Deichler sought employment with Davis

Kitch, who had the contract with the city of Lancaster to light the city

street lights. He started on July 1, 1882, but had to quit several days

later, "as he was unable to stand the fatigue of walking and the

exertion incident to such employment." In an affidavit, Kitch stated

that he "does not know of any lighter or easier employment than

lighting lamps and he [Deichler] is utterly unfitted for that work."

Deichler described his tortured life in a statement accompanying his

claim for a pension increase in December, 1888.

I'm nervous have continual pain inside of body my

wounds of knee and groin pain me. Can not hold my water any more, it

depresses (?) me. Had an operation three years ago, [unintelligible

words]. No sexual desire any more. Never had children. Never sick during

war. Have been laid up last year from pains and nervous.

Deichler's request for increase was denied. He

continued to request increases regularly, but each one was denied. In

1894 the examining surgeon wrote that Deichler, "seems demented &

melancholic," and that he was a "pale, tremulous man" with a "mind

enfeebled." Five years later, on February 24, at age 60, Deichler died

of pneumonia. That he lived as long as he did is remarkable, but the

Confederate bullet at Gettysburg and his subsequent wounds left him a

broken, unhappy, and lonely man, and slowly sapped his life from

him. [22]

Another of the casualties in the change of front by I

and A companies, was the acting 1st Sergeant of A Company, Ralph

Rickaby. The 28-year old, Irish-born sergeant was a shoemaker by

occupation. He enlisted in the 69th on August 23, 1861, and just over

two weeks later he married Ellen Kavenaugh. Six days after the wedding,

on September 17, the regiment shipped out to Washington, D.C. Rickaby's

luck held out through the battles of 1862 and early 1863, but at

Gettysburg a minnie ball hit him in the base of the neck, on the left

side, and passed obliquely through his back, exiting just to the left of

his spinal colunm. The bullet tore up the muscles and nerves in its path

and left Rickaby's arm partially paralyzed and his neck stiff. On August

27, 1864, Rickaby received his discharge from the army and a pension of

$5-1/3 a month. [23]

Rickaby apparently attempted to return to his former

trade as a shoemaker, but with a partially paralyzed left arm and a neck

that was so stiff he could not bend it forward without pain, it was a

hard go. As the years passed, instead of improving, Rickaby's condition

worsened, until in 1870 a board of examining surgeon's concluded that he

was "almost totally disabled for any kind of active manual labor. Cant

work continuously at anything." Starting June 7, 1870, Rickaby received

a pension increase to $6 a month. He continued to receive increases over

the years, until by 1891 he was receiving $12 a month. But considering

that Thomas Diver earned $4-5 a week in 1861 as a young printer,

Rickaby's pension in no way compensated for the occupation he lost when

a Confederate bullet paralyzed his arm at Gettysburg. How his marriage

was affected is not revealed in the documents in his pension file. No

doubt Ellen Rickaby had to perform manual labor to help the couple make

ends meet. Their life must have been difficult, and by 1891, at age 58,

Rickaby's health was such that he moved into the National Soldiers Home

in Alexandria, Virginia. He died there six years later, on September 16,

1897. As his widow, Ellen collected a pension, a paltry compensation for

the hard hand dealt her when her husband went down with a crippling

wound at Gettysburg. [24]

When companies A and I were ordered to fall back from

the wall to change front, for reasons unexplained, Sergeant Edward

Bushell, of Company A remained at the wall and was captured, probably

by the Confederates who poured down to overwhelm Company F. Bushell was

30 or 31 years old. Born in Tipperary, Ireland, he had emigrated to

this country and settled in Philadelphia, where he worked as a laborer.

On May 28, 1853, he married Mary McSwiggen at St. Paul's Church. Two

years later their first daughter, Mary Jane, was born, followed by Ellen

in 1858. In August, 1861, one month after the Union defeat at First

Manassas, Edward Bushell enlisted in the 69th

Pennsylvania. [25]

Bushell's life began to unravel with his capture at

Gettysburg. He and the other men from the regiment who were taken

prisoner were marched to Staunton, Virginia. The privations that Bushell

and the other prisoners from the 69th suffered was related by Patrick

Lester, a private from F Company. Lester wrote his wife on August 31,

1863, that for two months "we got only five ounses of bread to live on

dayly and that the worst part we had to march 8 days on 18 ounses of

flour Dear wife I cant tell you what we suffered." Bushell was

eventually taken by rail from Staunton to Richmond, where he remained,

presumably at Belle Isle, until he was paroled, on August 31, 1863. A

likely reason for his parole was his health. Surgeons diagnosed him with

"typhoids," and "hyper-trophy of heart." While he fought the illness

brought on by his imprisonment and exposure, his wife Mary fell ill and

died on November 5, 1863. Bushell left his young children in the care of

his father, Patrick. On December 31, 1863, he returned to his regiment,

but his health remained poor. At some time in the spring of 1864 he

deserted and returned to Philadelphia, where on April 14, he married

Margaret Gormly. Possibly Bushell hoped Margaret would provide a home

for his two children. If he did he was mistaken, for she would have

nothing to do with them and they remained in the uncertain care of their

grandfather. [26]

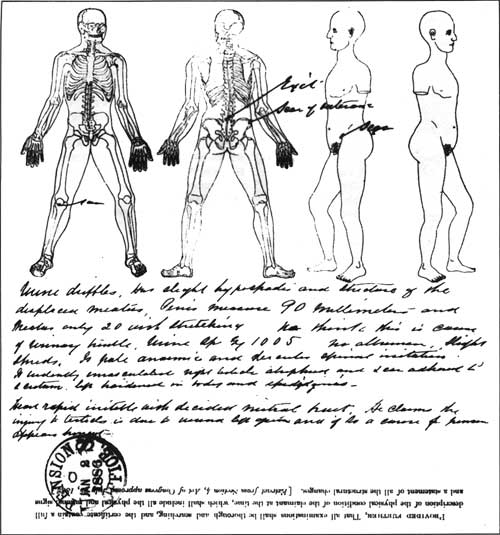

|

|

George Deichler's Pension Examination Record showing some of his

wounds. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Bushell never recovered from his capture and

imprisonment. He reported sick on June 9, 1864, and from then on he

continued to decline in health. In September, physicians reported he

suffered from rheumatism. Probably the typhoid fever contracted during his

imprisonment contributed to his condition. He worsened and was transported

to King Street Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia. There, at 10

p.m. on Sunday November 7, he died, one year and two days after his

first wife Mary had passed away. Although it cannot be proved, it is

highly likely that Bushell's death was directly linked to his capture on

the slopes of Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg, and his subsequent

imprisonment. His daughters, Mary Jane and Ellen, age 9 and 6

respectively, were now orphans in the care of a grandfather who had

little interest in their welfare. In either 1865 or 1866 he turned them

from his house onto the street. [27]

Fortunately for the children, their mother's sister,

Rosa Gallagher, took them in. In November 1866, probably soon after

throwing his grandchildren out of his home, Bushell's father applied

for a pension, claiming that since his son's death, "he has clothed and

fed his wards (the children) and provided them with all the necessaries

of life." For the next three years Pat Bushell pocketed the pension

meant to provide for his grandchildren. Then, on August 20, 1869, the

sisters of the dead children's mother struck a blow. They set the record

straight with the Pension Office, testifying that the children had lived

with Rosa Gallagher, not Pat Bushell "nearly ever since the death of

their Father." Furthermore, they avowed that Mr. Bushell, "has never

appropriated to them, or for their support one cent of said sum,

either for board clothing, or otherwise." And, as if to underscore his

unfitness to care for the children, they related that the grandfather

"was a drinking man, has turned his wife out of doors once or twice -

That she is not living with him now." Mary Bushell's sisters won their

point. On October 7, 1869, Patrick Bushell's pension was

stopped. [28]

Mary Jane and Ellen apparently lived out relatively

normal lives. Ellen married twice. There is no record whether Mary Jane

did. Both of them were still living in Philadelphia in 1920, when Ellen

wrote the Pension Office and attempted to re-activate her father's

pension. "Please try & see what you can do for two old sisters &

God will bless you," she wrote. [29]

Moments after Edward Bushell was seized by Pickett's

Virginians as a prisoner of war, Company F was overrun. Both

lieutenants, John Ryan and John Eagan were captured, along with eleven

enlisted men. One of them was 31-year old Patrick Lester. Two weeks

earlier, on June 19, he had written his wife, Jane, from Centreville,

Virginia:

Dear wife and children I take this opportunity of

writing these few lines to you to let you know that I am well after a

hard days march but we have about 80 miles more to go I cant tell how

manny died on the road.

No more at present

but remain your affectionate

husband Patrick Lester [30]

Patrick and Jane had been married for eight years

when he was captured at Gettysburg. Their marriage took place on

February 11, 1855, at St. John's Church in Philadelphia. Ten months

later their first child, Mary Jane, was born. She was followed two years

later by Elizabeth Ann, and then in 1860 the couple's third child,

Jessie Louisa, was born. Why, with three very young children to support,

Patrick Lester decided to enlist in the army is unknown. A likely

reason, and one that applied to many men in the enlisted ranks in the

regiment, was that the army, despite its dangers, offered a more stable

income than work as a common laborer. A laborer probably made about

$16.00 a month. The army offered regular employment and a pension if

you were killed or badly wounded and discharged. For a family man like

Lester, this may have been an attractive inducement. Whatever the

reason, he enrolled on August 19, 1861. [31]

Jane Lester did not hear from her husband again until

August 31, 1863, when he wrote her from Camp Parole at Annapolis,

Maryland:

My Deer wife and children

I take this opportunity of writing these few lines to

you hoping to find you and the children in good health. I am in very

poor health myself but I am as well as I can espect after the treatment

I got this last two months. . . I cant tell you what we

suffered. I hadent a [] but what the tuck away I hadent a shurt or shoe

or stocking on me sence I was taking. . . Dear Wife we got new

close when we landed heer the ar plenty to eat but cant eat it My stomack

is to weak. [32]

Pat had contracted chronic diarrhea while held at

Belle Isle. It was one of the reasons he had been paroled. With young

children to care for, and little money, Jane Lester could not rush down

to Annapolis to care for her husband. He was moved to St. John's

Hospital in Annapolis. On October 1, 1863, at Patrick's request, Mrs.

Abby Welch, a nurse in Lester's ward, wrote to Jane about his condition.

"I wish he could be at home with you," she wrote; "for he needs good

nursing, better than we are able to give him here. I think he is a dear

good man, he is so patient and uncomplaining." Mrs. Welch inserted one

hopeful piece of news; she believed Patrick would soon be transferred to

Philadelphia. The next day, October 2, hope became reality. Patrick was

granted a medical furlough until October 20, and transported to his

home in Philadelphia to convalesce. The joy of returning home to his

wife and children was tempered by Lester's medical condition, which

continued to worsen. On October 19, the day before Lester's furlough would

expire, Jane went to see John W. Wilson, a man she knew who was chief

clerk at the Sanitary Commission office in the city, to see if he could

do anything about extending her husband's furlough. Wilson went that day

to visit Pat Lester and found him gravely ill. He returned and explained

Lester's situation to the medical director, who said that Lester would

have to be transported to some army hospital before his furlough

expired, or he would be marked as a deserter. In obedience to this

absurd bit of army bureaucracy, Lester moved to the U. S. General

Hospital at Broad and Pine Streets. There, in the unhappy, sterile halls of

an army hospital, Patrick Lester died of chronic diarrhea on November

15, 1863. [33]

Ten days after her husband's death, Jane Lester filed

for a widow's pension. She was awarded the standard $8 a month, for a

private's wife. Tragedy struck her life again on July 27, 1865, when her

youngest daughter, 5-year old Jesse, was killed in an accidental

shooting. These traumatic blows must have taken their toll on Jane

Lester, and on March 11, 1872, she passed away. Her surviving children,

Mary Jane and Elizabeth, were raised by their grandfather, James

Williamson. Although the Lester pension files reveal little information

about them, the two children survived the tragedies of their childhood

and apparently led normal lives in the Philadelphia area.

Of the 2 officers and 15 enlisted men taken prisoner

in the 69th on July 3, 12 died in captivity or, like Lester and Edward

Bushell, as a result of their captivity. Of the five survivors, only two

men, 2nd Lieutenant John Eagen (Lacy) and Private Michael Gorman, both

of Company F, seem to have had constitutions of iron and retained their

health. Eagen lived until 1918. Gorman returned to the regiment after

his parole in March, 1864, and served out the rest of his military

service, was discharged, and never applied for a pension. The other

three, 1st Lieutenant John Ryan, 1st Sergeant Robert Doake, and Private

James Hand, all of Company F, were not as fortunate. Although they

survived their bout with disease that killed many of their comrades,

they never fully recovered their health. After his parole in August,

1863, Doake was hospitalized until February, 1864, when he transferred

to the Veteran Reserve Corps. Even this light duty proved too much for

him and he had to be discharged from the army. James Hand received his

parole in September, 1863, and, although he subsequently returned to the

regiment, he was in and out of hospitals until his discharge in August,

1864.

The experience of 26-year old Lieutenant Ryan gives

us some sense of what Hand and Doake suffered. Ryan had been wounded at

the Battle of Fredericksburg, suffering a contused wound over the liver.

The blow reportedly affected his stomach and caused him to "reject a

great part of his food." Four months later he returned to the regiment.

For 18 days following his capture at Gettysburg, during the march from

the battlefield to Staunton, Virginia, he received little food and slept

in "wet fields at night without any shelter from the rain." From

Staunton, Ryan and the others in the regiment were trained to Richmond,

where he and John Eagen entered Libby Prison. Bad as it was, conditions

at Libby (for officers) were better than those at Belle Isle (for

enlisted men). Nevertheless, due to the shortage of vegetables and

adequate food, Ryan contracted scurvy and dysentery. By the time of his

parole from prison on March 7, 1864, he reported that there were sores

all over his body, and an ulcer on his left leg. Several months in the

hospital convinced doctors that Ryan could not return to the field, and

he was discharged from the army on July 9, 1864. [34]

|

|

1st Lieutenant John Ryan, Co. F (Rev. Roy

Frampton)

|

During his convalescence, following his parole in

March, Ryan managed to get a furlough to return to Philadelphia, where

he married Catherine Golden on April 12, 1864, at St. Patrick's Church.

After his discharge, Ryan took a job with the Philadelphia and Reading

Railroad as a brakeman. On a fairly regular occasion Ryan would be

assailed by intense attacks of pain in his side over the liver, and

sometimes in his back or head. In an affidavit to the Pension Office he

described them:

These pains come and pass away frequently, and are

very intense while they last. The pain in my head comes in the sockets

of my eyes and almost blinds me while it remains there. It seems as

though a sharp instrument was piercing my brain. The pain in my back

extends from my hips to shoulder blades, causing great distress when I

stoop - cough - or sneeze, and especially in the morning

when arising from bed. [35]

In July, 1866 Ryan was involved in some type of

accident at work, which required the amputation of his right leg at the

middle of his thigh. What Ryan did for the next five years is unknown,

but in 1871 he and Catherine moved to Washington, D. C., where he took

a position on the disabled soldiers roll as a messenger at the U. S.

House of Representatives. The intense attacks of pain continued

frequently, assailing and prostrating Ryan for days at a time, leaving

him unable to care for himself. Some joy entered his life in December,

1881, when his wife gave birth to a baby boy. But it could not have been

easy for Catherine to care for the young child and a husband whose

health was precarious at best. [36]

Ryan's health continually deteriorated through the

1880's. His teeth blackened and decayed, and he suffered from gum

disease, the result of scurvy. He also developed heart disease, and a

frequent, hacking cough. Finally, on August 10, 1896, at age 59, Ryan

succumbed to his ailments and passed away. [37]

Clearly, capture on a Civil War battlefield was not a

ticket to safety from the dangers of combat. For most of the seventeen

men captured in the 69th, it was passage to an early grave or

permanently broken health, as it probably was for a large percentage of the

over 10,000 POW's of the battle. [38]

Only one man, other than Captain Thompson, lost his

life in Company F on July 3. This was a 40-year old private named Neil

McCafferty. He had been married for twelve years by 1863, and he and his

wife Catherine had three daughters, ages 10, 8, and 4. Their oldest

daughter, Mary had celebrated her tenth birthday on June 6, while her

father marched north with the Army of the Potomac to find and fight the

Army of Northern Virginia. A younger cousin of McCafferty's, 20-year

old Joseph McKeever, marched in the ranks of Company E. McCafferty had

taken McKeever under his wing and looked out for him. "He was like a

father to me," recalled McKeever [39]

When the shooting ceased in the combat at the angle,

someone in the regiment made his way down to Company E, found McKeever

and told him, "Huey, Neil McCafferty is dead." McKeever found him lying

beside the stone wall. He buried his cousin later that evening. He may

have also written Catherine to break the sad news to her. Somehow she

found the means to have her husband's body retrieved from the

battlefield and returned to Philadelphia, where he was buried in

Cathedral Cemetery on July 18. Four days later she applied for, and

received, a pension. In 1865 her youngest daughter, Annie, then age 9,

began experiencing severe epileptic seizures. By some means, Catherine

McCafferty held her family together, raised her daughters, and provided

for Annie's special needs. Catherine died in 1907. Margaret, the

youngest of the three daughters, stepped forth to care for her helpless

older sister, providing for her needs until Annie's death in 1934.

[40]

The close-quarter conflict that spread down the line

of the 69th following the destruction of Company F, fell particularly

hard on immigrants from County Tyrone, Ireland. Company G had a large

number of men from this part of northern Ireland, but there were others

spread throughout the other companies. Most of the men were in their

late 20's or early 30's, and worked as laborers, shoemakers,

bricklayers, or similar occupations. Possibly one of the first to fall,

was John Harvey Jr., a 28-year old private in Company A, and former

waiter in Philadelphia. Harvey was unique in the regiment for two

reasons; one, his 46-year old father, John Harvey Sr., a lawyer by

occupation, was also in Company A as a private, and two, John Jr. stood

6 feet 4-1/2 inches tall, a huge man in that regiment. His height may

have worked to his disadvantage on July 3, for a shell fragment hit him

in the head, possibly during the cannonade. Apparently he did not die

immediately from this bloody wound, for during the infantry attack he

received a minnie ball through the arm. His father was probably beside

him when he received these wounds and may have watched him die at the

farm of Peter Frey. They buried John Jr. on the east side of Frey's

house. [41]

The death of his son evidently had a profound effect

upon John, Sr. He had always been with the regiment and performed his

duty from the time of enlistment on August 23, 1861, except one brief

period in 1862 when he was reported sick in the hospital. On July 17,

1863, while the regiment was near Harper's Ferry, Virginia, John, Sr.

slipped away, taking his rifle and accouterments with him. In the fall

of 1863 he turned up in an army hospital in Washington, D. C., minus his

weapon and equipment. He had probably sold them to get money for drink.

Between his date of desertion and November, 1863, John Harvey, Sr. drank

himself to death. He died on November 11, 1863, of chronic alcoholism,

leaving a widow behind in Philadelphia. [42]

Another of the County Tyrone men took a prominent

part in the savage battle between Company D and Armistead's men who

overran Company F. He was Hugh Bradley, 28 years old, 5' 8" tall, black

hair, brown eyes, dark complexion, and known in the regiment as "quite a

savage sort of fellow." In the desperate melee with Armistead's

Virginians, Bradley turned his rifle into a club, "striking right and

left," until a Virginian crushed his skull with the butt end of a rifle

and killed him. [43].

Despite his reputation as a "savage" individual,

Hugh Bradley had been the sole support of his mother, Jane Bradley,

since 1860. Jane had lost her husband in Ireland and in 1841 she

immigrated to America with her nine children, and settled in

Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. What ages all of the children were is

unknown, and what became of them all is likewise not indicated. But

Jane relied solely upon her sons Hugh and Charles for support. Around

1860, Charles fell ill, so Jane came to count upon whatever Hugh could

send her of his $13 a month paycheck. One month after Hugh's death, his

mother applied for a pension. She received the standard $8 a month. The

sum of $96 a year could not sustain anyone, even in 1860's America, and

how Jane made ends meet is unknown. Somehow she did, until 1876, when

she stopped collecting her pension checks, probably because of

death. [44]

Ellen Mullin was another County Tyrone mother who

relied solely upon a son, 28-year old 2nd Lieutenant Michael Mullin, of

Company G, for her support. She had a sickly husband, James Mullin, who

suffered from heart disease, and since Michael had turned 17, Ellen

relied upon his income as a weaver or painter to support the

household. Michael's nomination by his commanding officer to fill a 2nd

Lieutenant vacancy in Company G in February, 1863, must have been

welcome news to the entire family, for it would more than double his 1st

Sergeant's salary, from $20.00 to $45.00 a month. His salary undoubtedly

was more than he had ever earned as a weaver/painter and would provide

the means to improve the standard of living of his mother and father.

There seems to have been some trouble with his confirmation at this

rank, but according to some records he received his commission on June

5, 1863. However, because the regiment was on the march after Lee, it

did not catch up to him before the battle. [45]

Whatever hopes his increased rank and pay may have

raised in Mullin and his parents died at Gettysburg. On July 3, a bullet

from one of Garnett's or Kemper's men hit the lieutenant in the left hip

and fractured it. He probably was carried first to the Peter Frey farm,

a 2nd Corps, 2nd Division hospital, but he was subsequently transported

to the Jacob Schwartz farm, which served as the 2nd Corps Field

Hospital. There, four days after his wound, Mullin died. Without the

means to remove her son's body, Ellen Mullin could only hope the army

would provide her son a proper burial. Initially he was buried with the

many others who died of their wounds at the makeshift hospital

cemetery, but later that fall or the next spring, his body was removed

to the Soldiers National Cemetery where he was laid to rest with his

comrades in the 69th. [46]

Ellen Mullin did not apply for a pension for her dead

son until June, 1864. By that time, her husband had been sick in bed

since January. He died on August 1. She received her pension, but the

Pension Office could not find any confirmation that her son had been

commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant, so they paid her at his last reported

rank - that of 1st Sergeant. Like most of the Irish wives and mothers of

men in the 69th, Ellen could not read or write, but she fought to get

what she knew was due her. Eventually, the truth was discovered, i.e.,

that Mullin's commission had not caught up to him before his death - a

trivial error in an army of over 90,000 men, but a matter of supreme

importance to a woman for whom $5 a month made a significant

difference in her life. She eventually won her struggle to get her

pension set at the rate paid to the mother of a 2nd Lieutenant. However,

when she called at the office of Dr. F. F. Burmeister, the pension

agent in Philadelphia and former surgeon of the 69th, she was informed

that she could not draw the pension as the rolls indicated she was dead.

Her attorney, Joseph E. Devitt wrote the Commissioner of Pensions to

state the situation and advise the commissioner, "She still

lives," then added, "Will you be good enough to have the roll

corrected as the claimant is very needy." Someone in the Pension Office

attended to the claim, and Ellen Mullin finally received her pension at

the rate to which she was entitled. [47]

The bloody conflict of July 3 felled all three field

officers of the 69th. Colonel O'Kane died that night from a wound he

received in the chest. Lieutenant Colonel Tschudy, who could have left

the field with an honorable wound on July 2, died with the men of

Company D in their hand-to-hand conflict. On the left of the regiment,

Major James Duffy took an ugly and intensely painful wound in the right

thigh from an exploding bullet. Following initial treatment on the

battlefield, the 25-year old Duffy was evacuated to Philadelphia,

accompanied by Private George H. Haws, a 29-year old plumber who was

detailed from Company A to serve as Duffy's personal servant. They

reached Duffy's home in the city on July 5. Haws said his goodbye

and vanished into the city. The regiment never saw him again, and the

last reported word on him was that he "went to sea." [48]

For Duffy's young wife, Catherine, his appearance

must have been shocking, for not only was the young major suffering

terribly from his wound, he was also tormented by sunstroke, which he

probably received during the march to Gettysburg. Catherine and James

had been married two years on April 11, 1863. The month of their happy

union had been the month the Union was shaken apart by events at Fort

Sumter, South Carolina. Duffy enjoyed a comfortable occupation as a

tavern keeper at Duffy's hotel, located near the corner of

Philadelphia's South Broad and Locust Streets. The tavern, no doubt, was

a lively place that spring of 1861, with the war as the main topic of

discussion. Duffy was caught up in the initial war euphoria, and he

secured a commission as captain in the 90-day 24th Pennsylvania

Infantry. When the regiment's enlistment ran out, Duffy went to work

recruiting what became Company A of the 69th Pennsylvania Volunteer

Infantry. [49]

For nearly two years Catherine Duffy lived with the

uncertainty and fear that only the wife of a soldier at war knows. The

news of every battle probably sent a shiver through her, until a letter

from James arrived to allay her worst fears. James apparently returned

home in February or March, 1862, on a furlough, for nine months later,

on November 19, 1862, the couple's first child, Margaret, was born. Four

months later, James had more good news. He had been promoted to major

on March 31. In addition to the increased salary, Catherine may have

been encouraged that the new position would place her husband in less

danger. On July 3, 1863, a Confederate bullet brought the family's good

luck to an end, but Catherine may still have counted herself fortunate.

Although badly wounded, James had been spared and was home. She would

have known that dozens of other wives and mothers of soldiers in the

69th were not so lucky [50]

The bullet that struck Duffy's thigh, or fragments

of it, remained lodged in his leg, and Catherine sent for James's

father, who brought Dr. William H. Pancoast and Professor J. Pancoast.

Dr. Pancoast operated on Duffy and removed the bullet. Duffy, according

to Pancoast, "suffered severely and for some time," and that he

"recovered slowly and with difficulty." By late September or early October,

1863, Duffy felt ready to return to the regiment. It proved to be a

premature decision for the wound had not healed properly, and the

exertions associated with the army's active operations at Bristoe

Station and Mine Run proved too much for Duffy. On December 18, 1863,

while the regiment was in winter quarters at Brandy Station, he received

his discharge from the army for medical disability [51]

James returned to civilian life, probably to his

former occupation as a tavern keeper. In October, 1866, Catherine gave

birth to their second child, a boy, whom they names James. But James,

Sr. continued to suffer the effects of his Gettysburg wound, and on

January 28, 1867, he applied for a pension. Former 69th Pennsylvania

regimental surgeon, F. F. Burmeister, examined him and rated him

one-half disabled, which qualified Duffy for $12.50 a month. Three

months later, Duffy applied for an increase to his pension and was

examined by a different surgeon, Philip Leidy. He reported that Duffy's

right leg was very weak, and that any amount of exertion or sitting for

long periods caused the former major pain. Changes in temperature also

affected the leg, at times rendering Duffy unable to work. Leidy

recommended Duffy's rating of disability be increased to 2/3's.

[52]

On October 10, 1868, Catherine gave birth to their

third child, a girl whom they named Catherine. Two months later, Duffy,

whose health continued to be poor, fell ill. His wound continued to

cause him trouble and probably contributed to the neuralgia (acute pain

that follows the course of a nerve) and anemia that the visiting

physician diagnosed. The next few months must have been unpleasant ones

in the Duffy household. Duffy's condition continued to worsen.

Catherine, with two young children and an infant to care for, had her

hands full. She probably had help from her family or James', for one

thing nearly all the pension files of soldiers in the 69th reveal is

that in most cases family members or friends looked after those in need.

What pension files do not reveal is the toll James' degenerating health

took upon Catherine Duffy. By June 7, 1869, Duffy's condition grew

serious. In addition to his suffering from his wound, neuralgia, and

anemia, Duffy developed chronic diarrhea. For nine days he suffered in

agony, until he died on June 16, another fatality of the Battle of

Gettysburg. [53]

Catherine Duffy raised her three children, ages 6, 2,

and 8 months old at the time of their father's death, until 1883. How

difficult this was for her is unknown. Probably her family, or James'

family, or friends, gave her assistance. She collected a widow's

pension, but it must have been hard for a widowed woman to raise young

children in that day. On November 11, 1883, Catherine Duffy died. James

and Maggie were over 16 and considered old enough to take care of

themselves. Young Catherine, almost 15 years old, was placed in the care

of Bernard McCaul, who was probably Catherine's brother. The single

bullet fired from an Enfield or Springfield Rifle that struck James

Duffy on July 3, 1863, at Gettysburg had brought much sorrow and

hardship to his family. One can only wonder what his children thought

about the battlefield that had ultimately robbed them of their father at

age 31? In 1887 the 69th raised a monument to mark their position at

Gettysburg, paid for by contributions by friends and former members of

the regiment. On the list of contributors published in the back of the

69th's regimental history is the name of James Duffy, Duffy's 21-year

old son, who gave $2.00. It was probably all he could afford, but it was

his way of saying that he had not forgotten the life his father had

sacrificed at Gettysburg many years before. [54]

Not all of the men lost by the 69th Pennsylvania as

a result of Gettysburg fell into the category of killed, wounded, or

captured. There is another group of casualties produced by war -

deserters. Often, these were chronic hard-cases, or regimental rif-raf,

who butted heads with army regulations and discipline until they decided

they had enough. But the eleven men who deserted from the 69th soon

after the battle, between July 5 and July 14, were not this brand of

soldiers. The military records of all but one of them indicate that they

were good soldiers and had always been present for duty, unless sick in

the hospital. [55]

The first soldier of the regiment to desert after

the battle, was George Haws, of Company A, whose story has already been

related. On July 6, while the regiment was near Sandy Hook, Maryland,

Patrick Harvey, of Company F, one of the few members of that company who

had come through the battle unscathed, deserted. The next day John

Cronin, of Company C, slipped away. On the 11th, two company A men left,

and Patrick Conuff, of Company D, who had been wounded on July 3,

deserted from the hospital. Thomas Lundy, 44, was listed as a deserter

on the 12th, and on the 13th, Corporal William Farrell, of Company C,

deserted from a hospital in Philadelphia, where he was recovering from

a wound received in the battle. Two more men, James Dolan and Edward

O'Brien, of Company H deserted on the 14th. The last of the eleven to

desert was John Harvey, Sr., whose circumstances have already been

told. [56]

Why had these men, all average soldiers who did their

duty, deserted their comrades? In fact, not all of them had deserted.

Thomas Lundy apparently straggled from the march on July 12, was

captured by Mosby's partisan cavalry, and then was re-captured by Union

cavalry. In the skirmish that ensued during his re-capture, Lundy lost

two fingers and ended up at Carver Hospital in Washington, D.C., where,

on August 5, he wrote his lieutenant to explain his whereabouts and have

his name removed from the rolls of the deserters. But the others had

deserted. John Eckard, a 27-year old private in Company A, was one of

two men who deserted from the regiment on the 11th. Eckard had deserted

once before, on August 28, 1862, but had returned to the regiment under

a presidential pardon to deserters on April 29, 1863. Except for the

period of his absence, Eckard had been in every battle and skirmish in

which the regiment had participated, but, according to his own account,

he had not seen his family for two years. After Gettysburg he decided to

leave, slipped away and somehow made his way back to Philadelphia.

Sometime in September, he was found and arrested and hauled back to the

regiment in the field. On October 1, 1863, Eckard was court-martialed

and ordered to forfeit all back pay, dating from the time of his

desertion, and to be charged $10 per month for nine months. Eckard had

been a common laborer before the war and his family evidently was quite

poor, so his court-martial sentence imposed a considerable hardship

upon him. In March, 1864, he appealed to the Secretary of War to be

allowed to re-enlist as a veteran volunteer, which he had not been

allowed to do because he remained under a sentence of court martial. "By

complying with my request you will be rendering a service to my family

as well as conferring a never to be forgotten favor on [me]," wrote

Eckard. Stanton granted Eckard permission to re-enlist. Five months

later he was captured at Ream's Station, Virginia, on August 25, 1864.

On October 9, 1864, he was sent to Salisbury Prison in North Carolina.

Slightly over two weeks later he died of disease. [57]

Two other deserters also returned to the regiment.

Patrick Harvey came back on September 27, 1863, bringing his rifle and

accouterments with him. Edward O'Brien was apprehended in Baltimore on

September 17. Both men were court martialed and docked pay, but both

remained with the regiment and served out the remainder of their

enlistments. Harvey even collected a pension after the war for

disability. The remaining six deserters, Corporal William Walton, of

Company A, Haws, Farrell, Conuff, Cronin, and Dolan, eluded capture and

never returned to the regiment. Walton had been promoted to corporal on

June 1, 1863, indicating that his company commander must have considered

him a good soldier. Farrell apparently had some trouble with Colonel

O'Kane, the nature of which is not specified. Whatever his situation, on

July 13, he left the hospital in Philadelphia where he was recovering

from his wound at Gettysburg, and walked into the United States Marine

Corps recruiting office to enlist under the name "William Giblin." He

served his six-year hitch honorably and received his discharge in 1869.

In the 1890's he applied for a pension. The pension examiners eventually

discovered that Farrell had been a deserter, but he had received an

honorable discharge from the Marine Corps, and for this service was

awarded a pension. [58]

A likely reason why most of these men deserted was

self-preservation. They had passed unscathed through battles like

Glendale, Savage Station, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and

Chancellorsville. Then came Gettysburg. Who knows what close calls or

other experiences each of these deserters had in that close-quarter

engagement, but they may have questioned whether they could or would

survive another such bloodbath. Or some of them may have simply reached

the limit of their tolerance for combat with Gettysburg. For the men who

never returned to the regiment, the war had permanently altered their

lives. At least for the duration of the war they could not return to the

life they had led previous to their enlistment, and for some they could

never go back.

This has been the story of only a handful of lives

that were abruptly, and permanently altered by the Battle of Gettysburg.

To learn what they endured gives us some slight idea of the awful

reality of what that battle really meant to tens of thousands of men,

woman and children. There was no pomp and circumstance, or bright flags,

or bayonets glistening in the sun - no glory to be won. There were

merely common people struggling with the harsh blows war had dealt

them. Most of the stories have unhappy endings: Susan Kelly, her two

cherished sons dead, left alone and dependent upon a government pension

to survive; George Deichler dying alone and unhappy; Jane Lester,

finding her joy at having her husband return from prison crushed by his

death from a hideous disease; Catherine Duffy, widowed at a young age

with three children ages six and under. Hopes and lives shattered - this

was the bitter fruit of that terrible battle. Yet, there is a quiet

heroism about them all; Henry Murray, with his eyes shot out, finding a

reason to live after all; George Deichler, who probably could have

sought and received a medical discharge for his Gettysburg wound, but

did not, returned, and paid a terrible price; Rosa Gallagher, who took

in the children of Edward Bushell when their grandfather turned them

from his house and then had the courage to stop him from collecting a

fraudulent pension; Catherine McCafferty, holding her family together

after her husband's death and raising their three daughters alone; and

there are many more whose stories will never be known. Theirs was a

different courage than that shown on the battlefield; it was the courage

to face life, when it would have been easier to give up and die.

NOTES

Using pension files at the National Archives is a

tedious process. I would like to thank Eric Campbell, Tom Desjardin, and

Justin Shaw for their help in this important part of the research. My

thanks also to Mike Musick, of the Archives staff who facilitated my

limited research time by pulling the regimental books and the military

records of the entire regiment for my use.

1 Anthony McDermott, A Brief

History of the 69th Regiment Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers,

(Philadelphia: D. J. Gallagher & Co., 1889), 28. U. S. War

Department, The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the

Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. XXVII, pt. 1, 430-431,

(hereafter cited as OR). Pennsylvania at Gettysburg, Vol. 1, 379.

Anthony McDermott to John Bachelder, 6/2/1886, Bachelder Papers, New

Hampshire Historical Society (NHHS), copy GNMP Library (hereafter cited

as Bachelder). Twenty-eight year old Alexander Webb assumed command of

the Philadelphia Brigade on June 28, 1863. He was a professional

soldier, but previous to taking command of the 2nd Brigade had served

strictly as a staff officer. He had a reputation of being a good

disciplinarian however, and since corps headquarters thought discipline

in the brigade had slipped under its previous commander, he was assigned

to its command. The combat experience of the 69th Pennsylvania at