|

BLACKS IN BLUE AND GRAY:

The African-American Contribution to the Waging of the Civil War

by Dr. Edward C. Smith

Professor, American University

Last year marked the 130th anniversary of the end of

the Civil War, the single most significant event in all of American

history. Since the war's end, nearly 65,000 books have been written on

the subject and new ones, examining every imaginable aspect of the

conflict, appear every year. Only Jesus Christ has been written about

more than Abraham Lincoln. Indeed, Sir Winston Churchill once said that

the American Civil War provided him with two of his most cherished

heroes, Lincoln and Lee, one for his consummate political skills, the

other for his military genius and of course during his own life-time

Churchill combined both fields of endeavor by serving his nation as both

soldier and statesman.

Until recently the most neglected area of civil war

studies had been the exploration of the role of blacks in both the North

and the South. However, the appearance of the award-winning film,

"Glory", provided audiences with the opportunity to learn that nearly

200,000 blacks served in the Union Army and nearly 40,000 of them gave

their lives in only two years of fighting since northern blacks did not

become participants in armed engagements until the Spring of 1863. To

date no similar film is in production that examines the service of

blacks in the army of the Confederacy.

Blacks have fought bravely in virtually all of

America's wars. During the Revolutionary War, more than 5,000 blacks

served in the Continental Army under the command of General George

Washington who praised them profusely for their military prowess and

patriotic spirit. A memorial to these valiant men (who all rejected the

British government's offer to grant them their immediate freedom) for

their service was approved by Congress in 1986 and will soon be unveiled

on the National mall located between the Washington Monument and the

Lincoln Memorial.

At the decisive battle of New Orleans, during the war

of 1812, general Andrew Jackson, later to become president, publicly

declared that the black troops that served in his units proved

themselves to be some of his most fierce fighters. These earlier black

patriots, all of whom must have searched deeply within themselves before

making their choice, knowing fully well that their courage and

commitment might receive neither recognition nor reward, nonetheless,

they served and sacrificed. In essence they made themselves the noble

forebearers of the Colin Powells of to day.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 made slavery

immensely profitable (for a short while) but it also quickly produced a

surplus population of black labor. With this new technology, one black

could effectively perform the work of ten. What then does an owner do

with the remaining nine, but mostly idle, workers? Does he destroy them?

No, of course not. After all, they are "living pieces of human

property" and therefore still very valuable.

Surely, most masters, especially the more

enlightened among them, had quickly discovered that the vast majority of

blacks were intelligent and quick-learners of language and other skills

and thus many field hands were transformed into master craftsmen in

carpentry, masonry, textiles, ironworks, etc. In 1822, the colony of

Liberia, on the west coast of Africa, was created by the American

Colonization Society, co-sponsored by the U.S. government, as a homeland

for those free blacks who wished to return to their ancestral soil. Only

a few thousand blacks chose to be repatriated back to Africa for the

simple reason that most, whether they were slaves or free, living in the

North or the South, had come to see America as "home" and more

importantly they had further come to see themselves as Americans of

African descent and not as African-Americans as so many do today.

So, as the Civil War era began to dawn, like whites,

blacks too were forced to select sides. The issue for them was somber

but rather simple, either they chose to fight to preserve the Union

(where they were treated at best as second-class citizens) or to fight

to establish a new southern nation entirely independent of the Union,

where they might possibly become accepted as social equals. If blacks

could fight for George Washington, it stands to reason that they could

fight for Jefferson Davis just as well.

To complicate matters further, let us not forget

that the Civil War was not begun to destroy slavery. Uncle Tom's

Cabin was published in 1852. Slavery was not abolished in the

nation's capital until ten years later on April 16, 1862. By then the

war had entered its second year. Furthermore, the final draft of the

Emancipation Proclamation was not authored until September 22, 1862,

only five days after the Union victory at Antietam. However, the

Proclamation did not go into effect until January 1, 1863. It was

essentially a presidential "Executive Order" which was cautiously

designed not to include the slave-holding border states of Delaware,

Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky (to prevent them from having any

incentive to join the confederacy) and would not become the "law of the

land" until the war was over and the Proclamation was transformed into

the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865.

Although President Lincoln was passionately opposed

to slavery, he was also a southerner who had married into a prominent

slave-owning family, the Todds of Kentucky. Three of his

brothers-in-law died fighting against him during the war. While campaigning

for president, he repeatedly reminded his audiences that he would not

contribute to the expansion of slavery into the western territories, but

neither would he employ the powers of his office to bring about

slavery's extinction. As far as he was concerned, "It can stay where it

is, as it is." After Lincoln's inauguration and the outbreak of the war

shortly afterwards, he often stated that if he could preserve the Union

by freeing all the slaves he would do it. Equally, he felt that if he

could preserve the Union by freeing none of the slaves he would also do

that. Thus, for Lincoln the preservation of the Union was first and

foremost the ultimate goal of the war. All else was secondary. After

all, lest we forget that when the president took his oath of office,

the man holding the Bible was U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B.

Taney, a slave-owning Marylander who presided over the 1857 "Dred

Scott" decision which effectively concluded that no blacks had any

rights that whites were required to respect. One can only imagine the

thoughts of each man as they looked into the other's eyes at the moment

of political triumph and impending national tragedy.

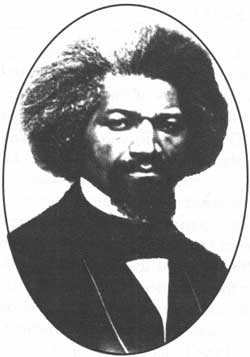

Fredrick Douglass had never met Abraham Lincoln in

person but he knew him well from what he saw of his thinking on paper.

Lincoln knew Douglass also through his writings, which greatly impressed

him. Also, his Vice President, Hannibal Hamlin, always spoke highly of

the self-educated runaway slave who had become one of the country's most

prominent authors and orators. He was a man that Hamlin encouraged the

President to meet with so that they could get to know each other

better. In a sense, no pun intended, Douglass was a "carbon-copy" of

Lincoln. Both men began from lowly socioeconomic origins and through a

rare and rich mixture of talent and tenacity they became the leaders of

their respective people, one by election, the other by acclamation.

|

Frederick Douglass

(National Archives)

|

Fredrick Douglass was nine years old when Thomas

Jefferson died in 1826. At that young age he had already discovered the

wonderful world of words and was beginning to make himself into the

voracious reader that he would later become. His reading interests

carried him into the distant lands and time of ancient Egypt and

classical Greece and Rome. He was thoroughly familiar with the writings

of Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, and Tacitus, and he was equally

well-versed in his understanding of classical literary works and

theatrical productions. His temperament and tastes also led him to

develop a love of William Shakespeare and the great thinkers of the 18th

century European Enlightenment. Above all, he was a great admirer of the

Old and New Testament.

As a young abolitionist working with many militant

New Englanders, he would often fire up many a mixed race crowd by

railing against the rank hypocrisy of the Declaration of Independence.

In his early manhood, Douglass held Jefferson in very low regard because

while Jefferson declared that "all men are created equal" he still

continued to own slaves. However, as Douglass matured in his judgements

and read more deeply into Jefferson's writings he came to see how

uncomfortable that he was for being a slave owner, that he knew it was

wrong for one man to own another and thereby deny him his god-given

freedom.

Douglass, having later adopted Jefferson as a

"spiritual father", thus began to realize that the true founding

document of the American experience was the Declaration, not the

Constitution, since the latter was a compromise statement which

rationalized slavery. Douglass then saw that it was his mission to urge

Lincoln to rise above the Constitution that he had sworn to uphold

(which Douglass considered in its current form to be a "lower" law) and

ascend to the higher law which was the essence of Jefferson's founding

document. In the beginning Lincoln resisted Douglass's urgings, feeling

that being associated with such radical views would only invite

political disaster and could possibly bring about defeat in his

campaign for reelection. But Douglass was unrelenting in his petitioning

of the President, both directly and through others, to seize the

opportunity to use the war as not only the means to achieve reunion but

as the instrument to destroy slavery and the southern way of life that

the "peculiar institution" sustained. Eventually—mostly as a

consequence of his own reflection and prayer—Lincoln came to see the

Declaration as Douglass did and on November 19, 1863 at Gettysburg he

let the nation and the world know that he was born anew when he said in

his famous Address:

"Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought

forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and

dedicated to the proposition that all men were created equal."

A score is twenty years so subtracting eighty seven

years from 1863 takes us to 1776, the writing of the Declaration of

Independence, not to 1789, the ratification of the Constitution.

Douglass continued to raise black soldiers for the

Union Army promising the President that his "sabel arm" would help to

bring him victory. Indeed, two of his own sons served in the 54th Mass.

Infantry Regiment which was commanded by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw who

died leading his troops in the valiant assault on Fort Wagner on the

South Carolina coast in July, 1863.

After the fall of Fort Sumter, President Lincoln

offered the command of soldiers he was raising to suppress the

rebellion to Colonel Robert E. Lee. It was a perfect choice. Lee had

been in the U.S. Army for nearly 35 years. His father was General George

Washington's Chief of Staff, his wife was Washington's

step-granddaughter. He was a hero of the Mexican War, former

Superintendent of West Point, and the capturer of John Brown during his

ill-fated raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1859. But

Lee, whose family helped to found the Union, refused the President's

offer to preserve it. Thus having rejected Lincoln to continue as his

Commander-and-Chief, he immediately retired to his 1,100 acre residence

at Arlington where he subsequently resigned his commission.

The Civil War was largely an American "tale of two

cities", Washington vs. Richmond, and a titanic struggle between two

opposing armies, the Army of the Potomac vs. the Army of Northern

Virginia. These enormous forces in the field were commanded by two of

the nation's greatest generals, Grant and Lee. They had fought beside

each other in Mexico and now were forced to fight against each other in

the epic battles that would determine forever the fate of the

nation.

Virginia was the most important Confederate state. It

is where 60% of all Civil War battles were fought. And it is Virginia's

soil that sired the nation's leading founders and gave us four of our

first five presidents: Washington, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. With

their capital moved from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond, Virginia, the

confederates could make the claim that they were not "rebels" but

revolutionaries, that it was they, not the Unionists, who were

the true sons of the founding fathers of 1776. After all, upon defeating

England the thirteen new states voluntarily entered the Union and

thus they reserved for themselves the right to voluntarily exit from the

Union. Such was then the very essence of the controversial concept,

"state's rights", the right for a state to not have to surrender its

sovereignty. Therefore, from the South's perspective, the North was

forcing it to stay—against its will—in the Union and such

coercive and "illegal" force must be resisted at all costs. The North

must not be allowed to "enslave" the South to the Union. Thus the voice

of Virginia's Patrick Henry could once again be heard throughout the

South, "Give me liberty, or give me death."

Throughout the Civil War, Virginia represented the

Confederacy's first "domino", should she fall, it was widely believed,

the remaining states would quickly follow. Also, Virginia was the

industrial heart of the South. In the Spring of 1861, the state had a

population of approximately 1,500,000, of whom one-third were black

(nearly 60,000 of whom were free). Clearly, such a large segment of the

population had the potential to influence events in this most crucial

and severely-tested state.

Virginia's blacks served the Confederacy as laborers

in the fields and factories; half of the workers at Richmond's famous

Tredegar Iron Works—the arsenal of the South—were black.

Blacks served as messengers and miners, teamsters and tailors, butchers

and bakers, and as soldiers and sailors. Black labor constructed the

105 buildings of the South's chief medical center, the Chimborazo

Hospital complex and were indispensable to its many and myriad medical

activities. Relative to most southern blacks, a large portion of those

in Virginia were literate and had been educated and trained by their

masters to become masters themselves in many crafts and technical

trades. This proved to be a tremendous resource of talent and skill that

the state could marshal for its defense.

The greatest contribution of blacks to the

confederate cause occurred during the long and costly Union siege of

Petersburg, Virginia, the gateway to Richmond. During the long struggle

beginning in June of 1864, black Union soldiers armed with bullets and

bayonets were opposed by black confederate soldiers and workers armed

with shovels, hammers, and axes. The confederate fortifications were

so formidable that Petersburg survived until its capitulation on April

2, 1865.

Throughout the war in Virginia, contrary to what many

northerners thought and hoped would happen, there were only a few

examples of black efforts to sabotage the confederate cause, yet they

had it in their power to wreak wholesale havoc throughout the South.

Black uprisings would certainly have forced the confederate government

to pull badly needed troops from the lines to provide police protection

for farms and families under threat of destruction. Furthermore, at any

time during the war, especially after the Emancipation Proclamation went

into effect, blacks could, with attendant risks, have escaped to nearby

Union lines but few chose to do so and instead remained at home and

became the most essential element in the southern infrastructure of

resistance to northern invasion. Over the years I have read the letters

of many southern deserters and I have yet to discover a single one from

a soldier who said that the reason he left his unit in the field was

because he feared that rampaging blacks on the homefront would exploit the

chaos and do harm to his farm or family.

It still remains a mystery to many in the North as to

why so many blacks remained loyal to the South. Contrary to conventional

wisdom, companies of black militia were widespread throughout the South

prior to the war. For example, Charleston, New Orleans, Lynchburg, and

numerous other southern communities had black militia units. The New

Orleans militia proudly served the confederacy during the first year of

the war, than forcibly swore allegiance to the Union after Admiral

David Farragut and General Benjamin Butler captured the city in April,

1862.

In the small town of Canton, Miss., is the probably

the most unusual confederate monument in the nation, dedicated to black

confederates. Erected some time before the turn of the century, the

handsome granite obelisk honors the "loyalty and service" of the blacks

who served in Harvey's Scouts, a crack cavalry unit that distinguished

itself while opposing general Sherman's march through Mississippi and

Georgia.

It has been argued forcefully that had President

Jefferson Davis been able to overcome his distaste for the idea of

enlisting black soldiers, the outcome of the war might have been quite

different. In his 1866 book, The American Conflict, Horace

Greeley holds that:

"Had the confederation met Lincoln's first

Proclamation of Freedom by an unqualified liberation of every slave in

the South and a proffer of a homestead to each of them who would

shoulder his musket and help achieve the independence of the confederacy, it

is by no means unlikely that their daring would have been crowned by

success. The blacks must have realized that Emancipation, immediate and

absolute, at the hands of those who had power not only to decree but to

enforce, was preferable to the limited, contingent, yet unsubstantial,

freedom promised by the Federal Executive."

But President Davis remained captive to the rhetoric

of such prominent and influential, deep-South "Fire-eaters" as Howell

Cobb who said:

"To make soldiers of our slaves is the most

pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began. The day you

make soldiers of them is the beginning of end of the revolution. If

slaves will make good soldiers then our whole theory of slavery is

wrong."

Although blacks were not officially admitted into

armed, confederate service until the Spring of 1865, many confederate

commanders in the field did not share such counter-productive

sentiments. One example was recorded by Dr. Lewis Steiner, Chief Inspector

of the U.S. Army Sanitary Commission for the Army of the Potomac, who

was an eyewitness to General Stonewall Jackson's 1862 occupation of

Fredrick, Maryland just before the Battle of Antietam. Steiner recorded

a description of the army's departure on Wednesday, September 10, 1862,

a movement that began at roughly 4 a.m. and continued to approximately

8 p.m.:

"The most liberal calculations could not give them

more than 64,000 men. Over 3,000 negroes must be included. They were

clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only cast-off or captured United

States uniforms, but in coats with southern buttons, state buttons,

etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by

white men in the rebel ranks.

Most of the negroes had arms, rifles, muskets,

sabers, bowie-knives, dirks, etc. They were supplied, in many instances,

with knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, etc., and were manifestly an

integral part of the Southern Confederacy Army. They were riding on horses

and mules, driving wagons, riding on caissons, in ambulances with the

staff of Generals, and mixed up with all the rebel horde. The fact was

patent, and rather interesting when considered in connection with the

horror rebels express at the suggestion of black soldiers being employed

for the National defense."

One of the members of Stonewall Jackson's immediate

circle of intimates was his chief cook and valet, Jim Lewis, who

reportedly cried uncontrollably during Jackson's deathwatch. Lewis was

held in such high esteem by other members of Jackson's personal

entourage that he was awarded by confederate leaders the high honor of

escorting Jackson's famous horse, "Little Sorrel", during his beloved

commander's state funeral in Richmond, 1863.

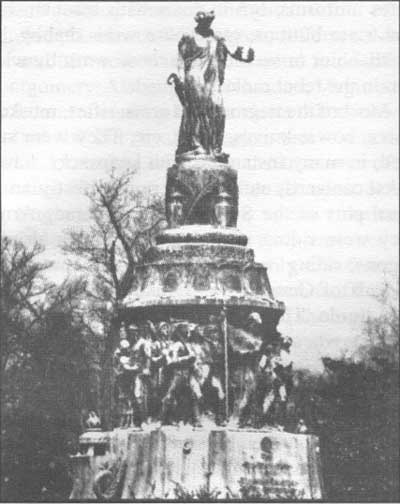

In Arlington National Cemetery, on the grounds of

what was before the Civil War the Lee family estate, there is an

impressive memorial to the Confederacy. It is Arlington's largest monument

and was unveiled to the public in June, 1914 on the 50th

anniversary of the founding of the cemetery by the federal government in

1864. The memorial is rich in symbolism and substance. Standing atop the

thirty-two foot structure is a large-than-life figure of a woman

representing the South. Her name is "New South" and her head is crowned

with olive leaves, her hand extends a laurel wreath toward the South

acknowledging the sacrifice of her fallen sons. Her right hand holds a

pruning hook resting on a plow stock. These symbols bring to life the

biblical passage inscribed at her feet: "And they shall beat their

swords into plow shares and their spears into pruning hooks."

Below the statue is a circular frieze of figures

illustrating the effect of war on both races. Among these bronze

representations of southern patriotism are three blacks: a soldier (in

uniform and armed), a mother, and a small child. Their prominent negroid

facial features are easily noticeable, thus there can be no doubt about

their racial identity. The sculptor, Moses Ezekel—a graduate of

the Virginia Military Institute who fought in the Battle of New

Market—placed the blacks side-by-side with other fighters and

families of the confederacy because he wanted the memorial to be a

truthful representation of the southern Civil War experience.

|

The Confederate Monument at Arlington

(NPS - Arlington National Cemetery)

|

Over the years black Americans have continued to

demonstrate their deep-seated patriotism and love of country even when

their country had no love for them. The U.S. Army was not racially

integrated until 1948 and the Korean War became the first time blacks

and whites fought together in the same units. During the 1960s, when the

civil rights struggle was raging throughout the South, with blacks being

beaten and killed for simply demonstrating for the purpose of securing

their basic rights as citizens, black men still fought and died in the

jungles of Vietnam in the tens of thousands and I, for one, have never

heard of a black American who burned his draft card or who fled to

Canada to avoid military service during that violent and divisive

era.

The colony of Jamestown was founded in 1608 and the

first blacks arrived on these shores from Africa in 1619. Since that

time African-Americans have become an inextricable and glorious part of

American history. There is no comparable experience in any other

country in the world.

|

|