|

PETTIGREW AND TRIMBLE:

The Rest of the Story

by Karlton Smith

In the historiography of the events of July 3, 1863,

much has been written concerning Major General George E. Pickett and his

division. At times, it seems as if they and they alone assaulted the

Union line on Cemetery Ridge. There has not been the same interest

concerning Major General Isaac R. Trimble and Brigadier General James

Johnston Pettigrew and their troops except, for the most part, in a

disparaging manner. For Trimble and Pettigrew, and their men, July 3,

proved to be a "day of immortal glory as of mournful disaster." [1]

Isaac Ridgeway Trimble was born in Culpepper County,

Virginia, on May 15, 1802. He graduated from the United States Military

Academy in 1822 and resigned his commission on May 31, 1832. He spent

most of the anti-bellum years working for the railroads. Trimble served

as Chief Engineer on the York and Wrightsville Railroad (1836-1838) and

as General Superintendent on the Philadelphia and Baltimore Central

(1859-1861). This experience gave Trimble knowledge of the area between

Harrisburg and Baltimore that may have proved useful to General Robert

E. Lee in the summer of 1863. [2]

|

Pettigrew (left), Trimble (right)

(GNMP; Clark's North Carolina Regiments, vol. 5)

|

In April of 1861, following the attack on the 6th

Massachusetts, Trimble accepted the command of a volunteer un-uniformed

corps of Baltimore troops. He also became involved in bridge burning

activities north of Baltimore. In May of 1861 Trimble accepted the

appointment of Colonel of Engineers in the Virginia State troops and on

August 9, 1861, he was commissioned a Brigadier General in the

Confederate States Army. In September he was charged with constructing

batteries along the Potomac River near Evansport, Virginia. In November

he reported to General Joseph E. Johnston at Manassas and was assigned

to the command of the Third Brigade, Second Division. Trimble, on March

3, 1862, was given control of all operations at Manassas during the

Confederate evacuation and was assigned to Richard S. Ewell's

Division. [3]

Trimble led his brigade with distinction during the

Valley Campaign, the Seven Day's, Cedar Run, and Second Manassas. He was

wounded at Second Manassas on August 29, 1862. This wound kept him out

of active service for several months. During his convalescence he was

promoted to Major General on January 17, 1863. [4]

On May 15, 1863, Trimble wrote to General Robert E.

Lee from Shocco Springs, North Carolina, where he was recovering from an

attack of camp erysipelas, respectfully requesting "to be placed in some

command in your Army of Northern Virginia, where I may, in your opinion,

be most useful to our cause." On May 20, Lee proposed to place Trimble

in command of the Shenandoah Valley and on May 25 Trimble accepted.

This appears to contradict the accepted version of events that Trimble

had no command during the Gettysburg Campaign. However, when Trimble

reported for duty at Staunton, Virginia, on June 22, he found that most

of his forces had been moved or were under orders to leave for Maryland.

Trimble joined Lee at Berryville, Virginia, on June 24 and at

Lee's request joined Ewell at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, on June 28.

Trimble remained with Ewell until about 11:00 a.m. on July 3, when he

assumed command of Major General William D. Pender's Division for the

attack on the Union center. [5]

James Johnston Pettigrew was born on July 4, 1828, at

the family estate of "Bonarva", Lake Scuppernong, Tyrrell County, North

Carolina. He entered the University of North Carolina at the age of 15

and graduated with such high marks that he was appointed an assistant

professor at the U. S. Naval Observatory in Washington. He began the

study of law in 1849 in Baltimore and later studied under his cousin, J.

L. Petigru, in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1850 he studied civil law

in Germany. Pettigrew's law studies led him to an acquaintance with the

German, French, Italian, Spanish, Arabic, and Hebrew languages. In

1852, he was appointed Secretary of Legation to the U. S. Minister at

the Court of Madrid. His experiences and observations in Spain led him

to privately publish Notes on Spain and the Spanish in

1861. [6]

In 1856, Pettigrew was elected to the South Carolina

Legislature where he issued "a thoughtful, well-balanced" minority

report against resumption of the slave trade. Perhaps because of this,

he failed to win re-election in 1858. He returned to Europe in 1859

hoping to win a commission in the Sardinian army in their fight against

Austria, but the war ended before he could take part. Upon returning to

Charleston, Pettigrew was elected Colonel of the South Carolina First

Regiment of Rifles of Charleston. [7]

Colonel Pettigrew was stationed on Sullivan's Island

during the Fort Sumter crises. When his regiment was not accepted into

Confederate service, he enlisted in the Hampton Legion. In July of

1861, without any solicitation on his part, Pettigrew was elected

Colonel of the 22nd North Carolina (originally the 12th North Carolina).

Pettigrew was stationed near Evansport, Virginia, from August 1861 to

March 1862, helping to construct and man the batteries placed there.

Pettigrew, at first, declined promotion to Brigadier General on the

grounds that he had never led troops in action, the promotion would

separate him from his regiment and that his services were of more value

in furthering the reenlistment and reorganization of his regiment. He

finally accepted the appointment on February 26, 1862. [8]

Pettigrew led his new command at the battle of Seven

Pines on June 1, 1862, where he was wounded and captured. He was first

sent to Baltimore and later transferred to Fort Delaware. On August 27,

1862, Pettigrew was ordered to be exchanged for Union Brigadier General

Thomas Turpin Crittenden. [9]

Pettigrew reported for duty on August 11, 1862, and a

week later was assigned to the former brigade of Brigadier General John

G. Martin, operating in North Carolina under Major General D.

H. Hill. On September 27, the North Carolina Senators

and Representatives requested that the state be organized into a

separate military district and suggested Pettigrew, who "possess the

full confidence of the people," to command. The Confederate War

Department agreed with the idea of a separate district, but pointed out

that Pettigrew could not be assigned without removing a major general

and three senior brigadiers. [10]

During the next several months Pettigrew led his

brigade with distinction in the operations against the Union occupation

of the North Carolina coast. In February, 1863, he was ordered to march

to Washington County, North Carolina, "to drive the enemy out of the

town of Plymouth and from the counties adjoining Washington." In March,

he took part in the expedition against New Bern and was in action at

Blount's Creek. While not involved in any "major" actions, this activity

provided Pettigrew's Brigade with considerable field and campaign

experience. By May 30, Pettigrew's Brigade had been assigned to Henry

Heth's Division, A. P. Hill's Corps, Army of Northern

Virginia. [11]

|

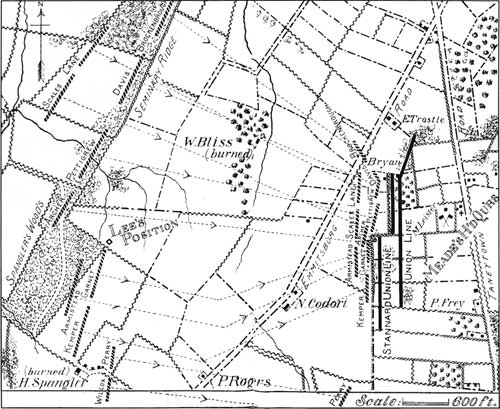

The Pickett/Pettigrew Charge, July 3, 1863

(Chester County (NY) Historical Society; click on

image for a PDF version)

|

By June 29, Heth's Division had reached Cashtown,

Pennsylvania, about nine miles west of Gettysburg. On the morning of

June 30, Heth ordered Pettigrew to go to Gettysburg ostensibly to

"search the town for supplies (shoes especially), and return the same

day." Without cavalry to screen his front, Heth probably wanted to know

what was in Gettysburg and used the "supplies" to justify his actions.

Pettigrew, from Seminary Ridge, observed Brigadier General John Buford's

Union Cavalry Division approaching Gettysburg from the south, along the

Emmitsburg Road, and slowly withdrew towards Cashtown. Pettigrew's

report was, apparently, discounted by Heth and Hill. Heth, with Hill's

permission, decided to take his whole division to Gettysburg the next

morning. [12]

Pettigrew's Brigade saw action on the afternoon of

July 1. They advanced, with Brockenbrough's Brigade on their left flank,

along the Chambersburg Pike from Herr's Ridge to McPherson's Ridge,

striking parts of Meredith's and Biddle's Brigades. Pettigrew was able

to drive both brigades from McPherson's Ridge, but at a high cost. (The

job of driving Union forces off Seminary Ridge would fall to Major

General William D. Pender's Division.) Pettigrew's Brigade, numbering

about 2581 officers and men, lost about 800 men on July 1, including the

commanding officer of the 26th North Carolina. [13]

At the end of the fighting on July 1, the brigade

bivouacked on Herr's Ridge and on the evening of July 2 moved a mile to

the right, behind A. P. Hill's guns on Seminary Ridge. [14]

Early on the morning of July 3, General Robert E.

Lee held a conference with some of his senior officers to finalize

plans for the day. Attending the conference were Lieutenant Generals

James Longstreet and A. P. Hill, Major General Henry Heth and at least

two members of Lee's staff. At this time Lee determined to launch an

attack against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. The

division of Major General George Edward Pickett, of Longstreet's Corps,

was chosen because it was the only fresh division on the field. It was

probably at this point, that Hill and/or Heth suggested Heth's Division

to fill out the column, supported by two brigades from Pender's

Division. These units just happened to be in the right position to join

the attack. Lee agreed and placed Longstreet in overall command of the

attacking forces. [15]

Heth had been slightly wounded on July 1 and had

turned command of his division over to General Pettigrew. Pender had

been severely wounded by artillery fire on July 2 and his place was

initially assumed by Brigadier General James H. Lane. At about 11:00 a.m.

on July 3 after the troops were in position, Lane was relieved of

division command by Major General Trimble. The four brigades under

Pettigrew numbered about 4500 and Trimble's two brigades numbered about

1800. [16]

Pettigrew's command was brought into line about 100

paces behind the line of Hill's guns on Seminary Ridge. His command,

from the right, consisted of Archer's Brigade, under Colonel Birket D.

Fry; Pettigrew's Brigade, under Colonel James Keith Marshall; the

brigade of Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis; and the brigade of

Colonel John M. Brockenbrough. There has been some debate over the years

as to the exact formation of the division. Normally, a regiment would be

deployed in two ranks, forming one line of battle. If the division

numbered about 4500 men this would yield a line length of about 3,682

feet. This length would have placed Brockenbrough's left flank opposite

the intersection of the Emmitsburg and Taneytown Roads, placing it too

far north. I believe the regiments were organized into division columns.

This consisted of deploying "the odd companies of the right, and the

even companies of the left wing, in rear of the companies on their

right and left respectively," and creating two lines of two ranks each.

The division frontage would have been cut almost in half, to about 1,841

feet, placing Brockenbrough's left flank just north of the Bliss Farm

(in the area of Lane's Brigade Tablet and near the entrance to McMillen

Woods Youth Camping) and nearly opposite the Emanuel Trostle

farm. [17]

Trimble's command, of about 1800 men, was formed

about 150 paces to the rear of Pettigrew's line. Trimble's line, about

1,500 feet, would have added depth and striking power to the center of

the attacking column while leaving the left flank, under Brockenbrough,

uncovered. This line consisted, from right to left, of Scales' Brigade,

under Colonel W. L. J. Lowrance, and the brigade of Brigadier General

James H. Lane. Trimble's other two brigades, under Brigadier General

Edward L. Thomas and Colonel Abner Perrin, were located along Long Lane,

just north of the Bliss Farm and about 300 yards from the crest of

Seminary Ridge. It is unclear what their role was to be in the attack. It

may be, that they were intended to help support the left flank of the

column and take advantage of any opportunity. [18]

Colonel Fry recalled that Pettigrew directed him to

see Pickett "at once and have an understanding as to the dress

in the advance...General Garnett, who commanded his left brigade, having

joined us, it was agreed that he would dress on my command." Fry's

brigade thus became the brigade of direction for the attacking

column. [19]

At about 1:00 p.m. the artillery bombardment

preceding the infantry attack began. Captain S. A. Ashe remembered that

the artillery fire "caused the solid fabric of the hills to labor and

shake, and filled the air with fire and smoke." General Davis stated

that the fire was "heavy and incessant" and reported two men killed and

21 wounded. Colonel Fry remembered that several officers and men in his

command were killed and wounded. Fry, himself, received a painful wound

in the right shoulder from a shell fragment, but still led his brigade

in the attack. [20]

Shortly before 3:00 p.m. the cannonade ceased.

Colonel Edward P. Alexander, in charge of Longstreet's artillery, wrote

that he sent word to Pickett and Pettigrew that the time had come to

advance. Longstreet gave his consent to Pickett, and presumably to

Pettigrew as well. Pettigrew rode to Colonel Marshall and said, "Now,

Colonel, for the honor of the good old North State, forward." Trimble

placed himself between the brigades of Lowrance and

Lane. [21]

As Pettigrew started to advance, there was some

confusion in the line. Fry and Marshall moved together, but Davis was a

little late in starting. Brockenbrough had divided his brigade into two

parts. Brockenbrough, commanding his right two regiments, moved after

Davis. Colonel Joseph Mayo, of the 47th Virginia, in charge of the left

two regiments, could not be found. His two regiments moved without him

and had to run to catch up with the rest of the brigade. This staggered

movement gave the impression of an echelon movement. Lieutenant Octavius

A. Wiggins, 37th North Carolina, Lane's Brigade, had a fine view of the

open field when Trimble led his men over Seminary Ridge. "It was a grand

sight," Wiggins wrote, "as far as the eye could see to the right and to

the left two lines of Confederate soldiers with waving banners pressing

on into the very jaws of death." Captain Louis G. Young, of Pettigrew's

staff, remembered that the "ground over which we had to pass was

perfectly open and numerous fences, some parallel and others oblique to

our line of battle, were formidable impediments in our

way" [22]

Before reaching the Bliss Farm, Pettigrew found his

line under Union artillery fire from guns on Cemetery Hill. Captain F.

M. Edgell, 1st New Hampshire, reported that he opened fire with case

shot. "I fired obliquely," Edgell wrote, "from my position upon the left

of the attacking column with destructive effect, as that wing was broken

and fled across the field to the woods." Most of this fire was being

directed against Brockenbrough's small brigade of about 500

men. [23]

Brockenbrough's Brigade also found itself under fire

from Colonel Franklin Sawyer's 8th Ohio Infantry, posted just west of

the Emmitsburg Road and north of the Bliss Farm. Sawyer stated that he

"advanced my reserve to the pickett front, and as the rebel line came

within 100 yards, we poured in a well-directed fire, which broke the

rebel line,..." While Brockenbrough's men would never admit to having

their line broken, their advance was clearly stopped by the combined

artillery and musketry fire. During this advance, there is no

indication that any of the Confederate troops in Long Lane assisted in

the attack. This non-involvement allowed Colonel Sawyer to

advance. [24]

After stopping Brockenbrough, Sawyer "changed front

forward on the left company" so he could now fire into the left flank of

Davis' Brigade. As Davis approached to within about 500 yards of the

main Union line, Woodruff's Battery I, 1st U. S. Artillery, stationed in

Ziegler's Grove, opened fire with double rounds of canister. Second

Lieutenant Tully McCrae reported that "the slaughter was dreadful. Never

was there such a splendid target for Light Artillery." Colonel Sawyer

had a close view of the effect of this fire

Arms, heads, blankets, guns and haversacks were

thrown and tossed into the air. Their track, as they advanced, was

strewn with dead and wounded. A moan went up from the field, distinctly

to be heard amid the storm of battle, but on they went, too much

enveloped in smoke and dust now to permit us to distinguish their line

or movements, for the mass appeared more like a cloud of moving smoke

and dust than a column of troops. Still it advanced amid the now deafening

roar of artillery and storm of battle. [25]

At about this time, or a little before, General

Longstreet sent a staff officer to warn Trimble about a threat to

Pettigrew's left. Lane and Lowrance, conducting a left oblique, moved to

take the place of Brockenbrough and reinforce Pettigrew's left flank.

Lowrance reported that troops from his front came tearing through his

ranks and caused many of the men to break until he ordered his men to

charge bayonets. Pettigrew's left was stopped and his line shifted to

the right to connect with Pickett's Division. This, along with a closing

of the ranks due to casualties, uncovered Lane's Brigade. This caused

it to advance more rapidly than Lowrance until it was corrected by

Trimble [26]

Pettigrew's three remaining brigades (Fry, Marshall,

and Davis) struck the plank fence along the Emmitsburg Road. By this

time regimental organization in Pettigrew's Division was breaking down

due to casualties, especially among the officers. Trimble wrote that

Pettigrew's right brigade (probably both Fry and Marshall) crossed the

fence but that the left halted in a deep ditch and went no further.

Trimble's command continued to advance. It is probable that some of

Davis' men became intermingled with Trimble's command as they started

to advance from the Emmitsburg Road. [27]

The Union infantry had been ordered to hold their

fire until the enemy reached the Emmitsburg Road. (Because the road does

not run parallel to Cemetery Ridge the distance varies - about 165 yards

from the Bryan Farm to the road, but about 250 yards from the Angle to

the road.) The Confederate troops were "mowed down like grain before

the reaper." The 126th New York, plus detachments from the 125th New

York and the 1st Massachusetts Sharpshooters, moved out of line to join

the 8th Ohio in firing into the left flank of Lane's troops. This would

eventually force Lane to detach the 23rd and 28th North Carolina to

cover the flank. When Brigadier General William Harrow and Colonel

Norman J. Hall moved their Union troops towards the copse of trees to

reinforce the Union line, they began firing towards the north across

the Angle. As there were no Confederate troops in the Angle at that

time, they had to be firing into Pettigrew's right flank. At one point

then, Pettigrew's command was receiving fire from three

directions. [28]

Despite this fire storm, Pettigrew's and Trimble's

men continued to advance. Some men reached the stone wall but there were

not enough of them to break the Union line. By this time, Trimble's

command had been reduced to about 500 men. [29]

Fry's Brigade hit the Union line just north of the

Angle, with some men possibly getting into the Angle itself. All but two

regimental flags were captured. The 1st Tennessee, 7th Tennessee, and

13th Alabama lost three color bearers, the last ones at the enemies'

works. Captain Norris, 7th Tennessee, saved his flag by tearing it from

the flag staff and hiding it under his shirt. The 1st Delaware and the

14th Connecticut, of Brigadier General Alexander Hays' Division,

launched counterattacks as the Confederate troops started falling

back. [30]

Assistant Surgeon George C. Underwood, 26th North

Carolina, recalled the capture of First Sergeant James M. Brooks and

David (or Nathaniel) Thomas, both of Company E, 26th North Carolina. As

they neared the stone wall, with Thomas carrying the flag, Union troops

(possibly from the 12th New Jersey) "called out to them, 'Come over on

this side of the Lord', and took them prisoners rather than fire at

them." [31]

Joseph G. Marble, 11th Mississippi, Davis' Brigade,

planted his regimental colors on the stone wall before he and the colors

were captured. Captain W. T. Magruder, Davis' Brigade adjutant, was

killed on the north side of the Bryan barn while urging his men on. The

loss of four color bearers in the 111th New York bears testimony to the

scale of the fighting at the wall. [32]

Trimble recalled that Lowrance's Brigade had been

firing from the Emmitsburg Road for about ten minutes before falling

back. Captain R. W. William, 13th North Carolina, remembered his cousin,

First Lieutenant W. H. Winchester, had his right foot shot off except

for the heel string. Colonel Lowrance reported that there were no

supports for the attacking column and that "without orders, the brigade

retreated, leaving many on the field unable to get off, and some, I

fear, unwilling to undertake the hazardous retreat." General Lane

reported that he was forced to withdraw because of the threat to his

left flank but, he later recalled, that his "was the last command to

leave the field and it did so under orders." [33]

Trimble had positioned himself between the brigades

of Lowrance and Lane and had reached a large elm tree on the west side

of the Emmitsburg Road. As Lowrance's men started to fall back Trimble

was hit in the left leg. His aide, seeing the troops falling back, asked

if he should try to rally the men. Trimble, realizing that the attack

had failed replied, "It's all over! let the men go back." When Lowrance

and Lane returned to Seminary Ridge, Trimble directed that the troops be

reformed immediately in rear of the artillery, to be prepared to met any

Union counterattack. [34]

Pettigrew, who was probably near Marshall's Brigade,

had his horse shot from under him and his left hand was shattered by a

"grape shot" (or more likely a piece of shell). Pettigrew, like Trimble,

directed his division to reform behind the guns on Seminary Ridge.

General Lee, after talking with Lieutenant Colonel Shepard, now

commanding Archer's Brigade (Colonel Fry having been wounded and captured),

met with Pettigrew. Lee directed him to rally his men and added,

"General, I am sorry to see you wounded; go to the

rear." [35]

Major General George E. Pickett was also met by

General Lee and told to rally his men for a possible Union

counterattack. As some of Lee's staff were trying to rally Pickett's men

on the reverse slope of Seminary Ridge, Pickett ordered his men to fall

back to their bivouac of the night before, almost three miles in the

rear. Pickett usually does not receive much criticism for seemingly

disobeying Lee's orders; while Trimble and Pettigrew never seem to

receive much credit for rallying their men to prepare for a possible

counterattack. [36]

Because most of Trimble's and Pettigrew's troops

fought on both July 1 and July 3, exact casualty figures for July 3 are

hard to determine. But it is possible to get a sense of the losses

sustained. The 11th Mississippi, Davis' Brigade, which was not engaged

on July 1, had entered the battle with 592 officers and men and lost 102

killed, 168 wounded, and 42 missing or captured, nearly 53% of the

troops engaged. Colonel Fry, leading Archer's Brigade, and Colonel

Marshall, leading Pettigrew's Brigade, were both wounded and captured.

Major J. Jones, 26th North Carolina, was the only field officer left in

Pettigrew's Brigade and assumed command despite having been struck by a

piece of shell on the first day and knocked down and stunned on the

third. Lane's Brigade reported losses for the two days at 178 killed,

376 wounded and 238 missing or captured out of 1734 engaged, nearly 46%

losses. The Scales'/Lowrance Brigade, reported 175 killed, 358

wounded and 171 missing or captured, out of 1351 engaged. Union

Brigadier General Alexander Hays, whose division bore the brunt of

Trimble and Pettigrew's attack, reported, "The angel of death alone can

produce such a field as was presented." [37]

Trimble, whose left leg had to be amputated by

Confederate surgeons, decided to stay behind when Lee left Gettysburg

and was captured by Union troops on July 6. Trimble was first taken to

the home of Robert McCurdy and later transferred to the Lutheran

Seminary. Some Union authorities expressed concern about Trimble's

ability to communicate with rebel sympathizers. They also emphasized that he

was a notorious bridge burner. Trimble was eventually transferred to the

U. S. General Hospital, Newton University, in Baltimore. [38]

On July 4, Lee's army began its retreat from

Gettysburg. On July 12, Pender's and Heth's Divisions were consolidated

under the command of General Heth. On the evening of July 13, Heth

received orders to move his command from Hagerstown to the pontoon

bridge at Falling Waters. On reaching an elevated range of hills about

a mile and a half from Falling Waters, Heth placed his command in line

of battle on either side of the road. At about 11:00 a.m., July 14, Heth

received orders that he was to follow Anderson's Division across the

river. Shortly afterwards, the rear guard was attacked by a portion of

the 6th Michigan Cavalry. Because of his wounded hand, Pettigrew was

unable to control his horse which reared and fell on him. While trying

to rise, Pettigrew was hit in the left side and seriously wounded.

Rather than take the chance of being captured again (as at Seven Pines),

Pettigrew insisted that he be taken along with the rest of his command.

He was carried by stretcher to the home of a Mr. Boyd at Bunker Hill,

Virginia, a distance of 22 miles. He died on the morning of July 17,

quietly and without pain. His remains were originally buried at

Raleigh, North Carolina, but in 1866 the remains were removed to the

family home at "Bonarva." In announcing Pettigrew's death to the

Secretary of War, General Lee stated that "The army has lost a brave

soldier and the Confederacy an accomplished officer." [39]

By November 9, General Trimble had been sent to

Johnson's Island, Ohio. In January, 1864, an effort was made to effect a

special exchange between Trimble and Major Harry White, 67th

Pennsylvania. Major General Benjamin F. Butler, Union Commissioner of

Exchange stated, "We shall only be spit upon for the offer." It seems

that Major White was a member of the Pennsylvania State Senate and the

Republican majority in the Senate depended upon the inclusion of Major

White. This request was turned down by the Confederate authorities as a

violation of the established cartels. [40]

On June 26, 1864, Trimble addressed a letter to

Brigadier General Henry D. Terry, Commanding Post Sandusky, complaining

of conditions on Johnson's Island. Among the complaints cited were

officers having to do hard labor, green wood for fuel and the poor

quality of the meat and water. Most of the complaints were judged to be

"without substantial foundation." [41]

In November of 1864, the Confederate government was

permitted to deliver 1000 bales of cotton to Mobile "to be forwarded to

the city of New York and there sold, the proceeds to be applied to the

benefit of our prisoners..." Trimble, then at Fort Warren, Boston

Harbor, had been selected, by the Confederate government, as to whom

the consignment was to be made and the officer responsible for the

purchase of supplies. While General Grant seems to have agreed with this

assignment, Secretary of War Stanton did not. "He cannot be trusted,"

Stanton said, "and is the most dangerous rebel in our

hands." [42]

On March 8, 1865, General Grant directed that Trimble

be sent to City Point, Virginia, to be exchanged. Trimble left Fort

Warren on March 10. He apparently did not arrive in time to join Lee at

Appomattox as his name does not appear on the list of parolees. Trimble

returned to his home in Baltimore where he died on January 2,

1888. [43]

While they rarely receive the recognition they

deserve for their services on July 3, it is clear that Major General

Isaac R. Trimble and Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew performed

to the best of their abilities. Pettigrew assumed command of Heth's

depleted division on July 1, and Trimble assumed command of Pender's

reduced division only two hours before the cannonade opened. By almost

all accounts, except those left by Pickett's Virginians, both officers

gallantly led their troops in Longstreet's assault. If they were unable

to break the Union line it was through no fault of theirs or their

troops. Both were wounded while leading their men and both succeeded in

rallying their commands on Seminary Ridge, in obedience to Lee's orders.

Pettigrew was wounded on July 3 and mortally wounded at Falling Waters

on July 14. Trimble was also wounded on July 3 and was later confined as

a prisoner of war until March of 1865. While the casualties incurred by

their commands would make July 3, 1863, a day of "mournful disaster,"

Trimble's and Pettigrew's leadership would also make it a "day of

immortal glory."

NOTES

1 Captain S.A. Ashe, "The

Pettigrew-Pickett Charge." Histories of the Several Regiments and

Battalions from North Carolina, ed. Walter Clark, 5 volumes, 1901

(reprint by Broadfoot Bookmark, 1982), Vol. V, 159; hereafter cited as

Clark.

2 Dictionary of American

Biography (Charles Scribners Sons, 1946), Vol. XVII, 641-42.

Hereafter cited as DAB; George W. Cullum, Biographical

Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U S. Military Academy at

West Point, NY (Houghton-Mifflin, Co., Boston, 1891), Vol. 1,

228.

3 Bert Rhett Talbert, Maryland: The

South's First Casualty (Berryville, VA, Rockbridge Publishing Co.,

1995), 124; DAB, 641-42; Southern Historical Society

Papers (Richmond, VA; reprint: Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint Co.,

1977), Vol. 2, 70; hereafter cited as SHSP; U.S. Department of

War, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official records

of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, 1880-1901), Series

I, Vol. V, 961; Vol. LI, part 2, 730; hereafter cited as OR. One

of the regiments at Evansport was the 22nd NC commanded by Col. James

Johnston Pettigrew.

4 Ezra J. Warner, Generals in

Gray (Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge and London,

1957), 310. For more information on Trimble's actions in 1862 see his

official reports in OR, I, Vol. XII (2), 557 and 646.

5 OR, I, Vol. XXV (2), 801-2,

812, 822; SHSP, Vol. XXVI (1898), 118-121; OR, I, Vol.

XXVII (2), 659; David L. and Audrey J. Ladd, eds, The Bachelder

Papers (Dayton, OH: Morningside House, Inc. 1994), Vol. II, 932,

cited hereafter as Bachelder.

6 DAB, Vol. XIV, 516; Warner,

237-8; W.R. Bond, Pickett or Pettigrew? (Scotland Neck, NC:

W.L.L. Hall, 2nd ed., 1888), 5-6, hereafter cited as Bond.

7 Ibid.

8 OR, I, I, 35-6, 268, 297;

OR, I, LI (2), 234, 478; DAB, 516; Clark, Vol. II, 161,

167; Bond, 7; SHSP, Vol. II, 60.

9 OR, Series II, Vol. III, 645,

891; Vol. IV. 18, 25-6, 450. Warner, Generals in Blue (Louisiana

State University Press, Baton Rouge and London, 1964), 101.

10 OR, I, Vol. IX, 480; Vol. LI

(2), 627-8.

11 Ibid., Vol. XVIII, 750, 788, 807,

874-5, 974; Vol. XXV (2), 840.

12 Ibid., Vol. XXVII (2), 637; Clark,

Vol. V, 115; SHSP, Vol. IV, 1879), 157.

13 Edwin B. Coddington, The

Gettysburg Campaign (Dayton, OH: Morningside Bookshop, 1979), 293;

John W. Busey and David G. Martin, Regimental Strengths and Losses at

Gettysburg (Hightstown, NJ: Longstreet House, 1964) 290; OR,

I, Vol. XXVII (2), 637-8, 642-3.

14 OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2),

643.

15 Armistead A. Long, Memoirs of

Robert E. Lee (New York, 1886), 288; OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2),

308, 359.

16 OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2),

659.

17 Silas Casey, Infantry

Tactics (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862; reprint, Dayton, OH:

Morningside House Press, 1985), 202-09; OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2),

359.

18 OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2),

659.

19 SHSP, Vol. V, 140;

SHSP, Vol. VII, 92; OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2), 650.

20 Clark, Vol. V, 140; OR, I,

Vol. XXVII (2), 650; SHSP, Vol. VII, 92.

21 E.P. Alexander letter to his

father, dated July 17, 1863, in the "Alexander-Hillhouse Papers,"

Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina (copy in

GNMP files); OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2), 360; Clark, Vol. II, 365.

22 Clark, Vol. II, 651; OR, I,

Vol. XXVII (2), 644.

23 OR, I, Vol. XXVII (1), 750

and 893.

24 Ibid., 462. Although there is no

official indication that the brigades in Long Lane did anything more

than watch the charge, at least one unofficial source indicates that

General Thomas did issue an order to advance, but only the 35th GA did

so (see Heroes and Martyrs of Georgia by James Madison Faban

(1864), 138-9).

25 Ibid. Franklin Sawyer, A

Military History of the 8th Regiment Ohio Vol. Inf'y (Cleveland, OH:

Fairbanks & Co., 1881; reprint, Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press,

1994), 131. "Reminiscences about Gettysburg, 30 Mar 1904" by Tully

McCrae, MS in private collection, George Stanly Smith, Sacketts Harbor,

NY (copy in GNMP files).

26 G. Moxley Sorrel, Recollections

of a Confederate Staff Officer (Jackson, TN: McGowat-Mercer Press,

Inc., 1958), 164; OR, I, XXVII (2), 659, 671-2.

27 Bachelder, Vol. II, 933.

28 William P. Seville, History of

the First Regiment Delaware Volunteers (Wilmington, DE, 1884;

reprint, Baltimore, MD: Longstreet House, 1986), 81; Clark, Vol. V, 190;

Bachelder, Vol. I, 408; OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2), 651.

29 OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2),

672.

30 Ibid., 647; OR I, Vol. XXVII

(1), 467, 469, 480.

31 Clark, Vol. II, 374.

32 New York Monuments Commission for

the Battlefields of Gettysburg and Chattanooga, The Final Report on

the Battlefield of Gettysburg (cover title New York at

Gettysburg; Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1900), Vol. 2, 803;

Mississippi Historical Society, Vol. II (1918), 561.

33 Clark, Vol. I, 672; Vol. II, 478;

OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2) 666, 672; Bachelder, Vol. II, 934.

34 Bachelder, Vol. II, 933-4; Gregory

A. Coco, A Vast Sea of Misery (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas

Publications, 1988), 36; OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2), 667.

35 Clark, Vol. II, 366; Bond, 7;

George R. Stewart, Pickett's Charge (Cambridge, MA: Riverside

Press, 1959), 256.

36 Jacob Hoke, The Great

Invasion (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1959), 426-7.

37 Busey and Martin, 290, 292; Clark,

Vol. V, 111; OR, I, Vol. XXVII (1), 454; Vol. XXVII (2), 645.

38 Coco, 36; OR, II, Vol. VI

103, 107-8, 451; I, Vol. XXVII (1), 646, 663.

39 OR, I, Vol. XXVII (2), 667,

639-41; I, Vol. XXVII (3), 1016. Clark, Vol. II 376-7; DAB

642.

40 OR, II, Vol. VI, 486, 839,

871; Vol. VIII, 380.

41 Ibid., Vol. VI, 900-01.

42 Ibid., Vol. VII, 1117, 1131

43 Ibid., Vol. VIII, 366, 375;

SHSP, Vol. XV; DAB, 642.

|

|