|

WE SAVED THE LINE FROM BEING BROKEN:

Freeman McGilvery, John Bigelow, Charles Reed and the Battle of Gettysburg

by Eric Campbell

If History is written Truthfully I feel confident I

shall receive a large share of the Credit of saving our Army from a

Defeat on the 2d of July 1863 at Gettysburg... [1]

Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery wrote these words less

than two weeks after participating in one the most critical battles of

the American Civil War. He had a right to be proud of his actions, in

which he commanded several Union artillery batteries that were critical

in determining the outcome of the fighting on the second day of the

battle.

Yet, except for the grand bombardment preceding

Longstreet's Assault on July 3, most general histories of Gettysburg

overlook, or even ignore completely the role of the artillery arm during

the battle. This is unfortunate, for artillery did have a

significant, even decisive influence at Gettysburg. This paper, by

following the personal experiences of three Union soldiers, will

examine a crucial, yet often overlooked action, and reveal how Union

artillery turned back a significant Confederate threat during the early

evening of July 2, 1863.

The three individuals used for this study, while

exceptional in many ways, also are representative of the typical Union

artilleryman, from field officer to private, who served at Gettysburg.

They are: Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery, Captain John Bigelow, and Bugler

Charles Wellington Reed. Before what they did can be discussed, a short

introduction to each will define who these men were.

|

Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery (left), Capt. John Bigelow (center),

Bugler Charles Reed (right)

(Maine State

Archives, GNMP, Library of Congress)

|

By the fall of 1861, Freeman McGilvery, 37,

was a man of extensive experience, having traveled the world for nearly

20 years as a sea captain. Having decided to join the Union army, he

raised and organized the 6th Maine Battery that winter and was

commissioned its captain on January 1, 1862. [2]

McGilvery had commanded men for over fifteen years

and "had the coolness and rapidity of thought and action, which

at...critical moments are required of an artillery officer." His

leadership experience had also taught him the importance of discipline.

He once wrote:

I...have a tolerable appreciation of the value of

discipline in situations where bodies of men at times [are] required to

be as a unit to him who commands them. 10 men well disciplined under the

control of an energetic bold leader will easily vanquish 20 in the loose

& unrestrained character of a mob, & so of Thousands & tens

of Thousands. However, McGilvery also realized that "Discipline does

not infer Tyranny. . ." [3]

He must have drawn upon all of this knowledge, for

government bureaucracy and red tape delayed the arming and equipping of

the battery until June when, "[b]efore it was properly drilled," the

unit was ordered to the front. Given one month to prepare, McGilvery led

the battery into its first action on August 9, 1862, at Cedar Mountain,

where it was positioned on the extreme left of the Union line and was

called upon to repulse "a most determined attack made by the enemy..."

McGilvery later wrote, "I was ordered to hold the position at all

hazards as long as I had ammunition." His delaying action lasted "at

least 20 minutes," and according to his commander, Brig. Gen.

Christopher Augur "had saved the division from being destroyed or taken

prisoners." "I had a desperate fight," McGilvery wrote. Indeed, the last

gun was "brought off the field in the face of the enemy's infantry not

fifty yards distant." [4]

Several skirmishes quickly followed McGilvery's

initiation to combat, before he led the battery at Second Manassas on

August 30, where he and his battery once again found themselves facing

overwhelming numbers as Confederate assaults struck the Union line. The

battery fought until all its "support had left and all the horses of two

guns had been killed." McGilvery "finding it useless to maintain the

unequal contest, and the enemy gaining his rear, gave orders to fall

back," but not before he had lost two guns. The other four pieces

rallied 1,400 yards to the rear where, in the growing darkness,

McGilvery made another stand, thus allowing "all of our troops" time to

escape. The captain reported that his "battery was the last to leave the

field." [5] These desperate delaying actions justified

McGilvery's insistence upon discipline and the experiences would serve

him well ten months later at Gettysburg.

McGilvery commanded the battery, though it was not

engaged, at the battles of South Mountain and Sharpsburg, before his

promotion to major, Maine Artillery, in February, 1863. [6] On May 12, 1863, he joined the Army of the Potomac when

he was assigned command of the 1st Volunteer Brigade, Artillery

Reserve, the unit he would eventually lead at Gettysburg. [7]

It did not take the newly promoted major long to

gain the respect of his superiors. On June 23 McGilvery was promoted to

lieutenant colonel. Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery,

remembered McGilvery as "a cool and clear headed officer," a fact which

he would prove on July 2, 1863. [8]

Being born and raised in an upper-class Boston

family, it is not surprising that John Bigelow entered Harvard

College in the fall of 1857 at the age of sixteen. Though his academic

performance was not outstanding, Harvard gave Bigelow something that

would prove invaluable on numerous battlefields: self-discipline and the

"self-possession to stand alone." [9] With the threat

of war looming, and just three months before his graduation, Bigelow

enlisted in the military on April 4, 1861, the first member of his class

to do so. He had joined the 2nd Massachusetts Battery and was quickly

promoted to lieutenant. During his brief stint with the battery, Bigelow

learned the mechanics of artillery and responsibilities of command. [10]

In December, 1861, Bigelow accepted the adjutant

lieutenancy of the 1st Battalion of Maryland Artillery, which was soon

attached to the Army of the Potomac. His duties were mostly

administrative, such as transmitting new orders from the chief of

artillery during the army's reorganization of that branch of service.

This experience broadened Bigelow's understanding of leadership and the

proper management of artillery. [11]

The young officer saw combat for the first time on

July 1, 1862, when the battalion was heavily engaged at Malvern Hill

outside Richmond. A section of Battery B of the battalion lost its

lieutenant and many of its men. Lt. Bigelow took command just as the

rest of the demoralized crew seemed in the act of "deserting their

gun[s]." Ordering the men back into action, Bigelow then led by example,

physically pushing one of the pieces into a new position. While in this

act, he was "shot through the wrist of the right arm." Despite the

intense pain, and not willing to let the section lose its second

commander in a matter of minutes, Bigelow fashioned a sling for "the

injured arm and kept on firing." His commander, Capt. Alonzo Snow,

reported that his lieutenant "took charge of [this] section and fought

it gallantly until the close of the fight." [12] It

would not be the last time one of Bigelow's superiors referred to his

conduct as "gallant."

After a four-month furlough, Bigelow returned in time

to participate in the Battle of Fredericksburg. By January, 1863,

however, "suffering in health," he resigned his commission and returned

home. His convalescence did not last long though, for "annoyed so much

at the comments of the papers and people on the conduct of the war,"

John Bigelow decided he would fight again. In a February 9, 1863, letter

to Massachusetts Gov. John Andrew, Bigelow wrote because "the demands of

the country are as urgent today as at the outbreak of the rebellion, I

have the honor to offer my services..." [13]

Andrews, needing the services of veteran officers

like Bigelow, quickly accepted and offered him the captaincy of the 9th

Massachusetts Battery. Organized in August, 1862, the battery had given

the governor constant trouble. Most of this stemmed from poor leadership

provided by the original captain and from the fact that the battery had

spent its entire existence pulling garrison duty in the Washington

defenses. Morale was low, discipline was lacking and the battery was in

turmoil. Gov. Andrews warned Bigelow "you will find them thoroughly

demoralized; they require an officer of experience; they need

discipline; your work will be difficult." [14]

Indeed, Bigelow recalled finding the battery "within

the earthworks of Washington, demoralized and unhappy because the men

felt they were only playing soldiers, for which they had not enlisted."

The newly promoted captain, placing the same importance on discipline as

McGilvery, cracked down. One of the men in the battery did not think

much of his new commanding officer, writing that Bigelow was "a regular

aristocrat...He is worse than any regular that ever breathed." [15] That soldier's name was Charles Wellington Reed.

Born in Charlestown, Massachusetts on April 1, 1841,

Charles Wellington Reed was the third child of Joseph and Roxanna

Reed. Though Reed's ancestry was rich—his great-grandfather Swithin Reed

immigrated to America in 1740; his grandfather Isaac Richardson had been

wounded at the Battle of Lexington during the Revolution; his father had

served during the Mexican War—his immediate family's financial and

social status was only moderately acceptable. [16]

Of average height and slight in built, Reed was

articulate, industrious, eager and had a talent for drawing, art and

music. After graduating from public schools of Charlestown and Boston,

Reed was working independently as an illustrator/lithographer when the

war began. Unsure of his future career path and seeking an opportunity

to advance his talents, Reed enlisted as bugler in the 9th Massachusetts

Battery on August 2, 1862, for three years or the end of the war. [17]

To Reed the war seemed a great adventure, giving him

a chance to travel, visit sites he had only read about and be a witness

to what he realized was a great event in history. Not only did he

witness it, but Reed recorded much of what he saw, illustrating most of

his letters with drawings and filling several sketch books throughout

the war.

The arrival of the battery's new captain in late

February, 1863, changed the lax and somewhat carefree lives of the men

in the 9th Massachusetts Battery. Some, including Reed, thought Bigelow

was a tyrant, the bugler writing, "he dont have...the feelings for his

men as a slave owner for his slaves...he has been order[ing] eight roll

call's a day. in fact they are regular dress parades which precede all

the drill call's[,] stable, and water calls..." [18]

Realizing the importance of discipline, Bigelow

instilled it through strictness to regulation, repeated drilling and

insistence on the unquestioning obedience of orders. Not surprisingly,

the battery made steady improvement, one soldier noting: "Our camp, from

headquarters to stables, felt a new influence." Even Reed wrote that

Bigelow "understands his business, lately he has relaxed his

strictness...I think his strictness was to make the men know what he

is." [19]

Throughout that spring the battery's morale,

discipline and confidence grew steadily. One of the men later wrote, "we

felt we were making rapid strides toward a position in which we can be

efficient in any place." They would certainly need to be, for their

first experience in combat was to take place that summer at a

Pennsylvania crossroads town called Gettysburg. [20]

GETTYSBURG

In reaction to the second Confederate invasion of the

north during the war, the Army of the Potomac marched northward in June,

1863. Its route through northern Virginia passed by the outer defenses

of Washington, from which the army gained reinforcements from various

garrison troops. On June 25, 1863, the 9th Massachusetts Battery, found

itself marching as part of this massive army. At that time the battery

consisted of 104 officers and men, 110 horses and six bronze smoothbore

Napoleons. The men soon discovered they had been assigned to the 1st

Volunteer Brigade, Artillery Reserve, commanded by Lt. Col. Freeman

McGilvery [21]

It was here that McGilvery, Bigelow and Reed were

drawn together. Although they could not foresee it, these three men,

along with their comrades of the artillery arm, would play an important

role in determining the final outcome of the approaching battle.

McGilvery's brigade arrived on the battlefield by

mid-morning of July 2, 1863, as part of the on-going concentration of

the Union army. The battle had begun the day before as elements of both

armies clashed outside Gettysburg, with the end result being the retreat

of the Union forces to a range of hills and ridges located south of

town.

Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commanding the Army of the

Potomac, had decided to await Confederate movements and was arranging

his battle line for a defensive struggle. The Artillery Reserve was thus

placed behind the lines and held in readiness to be used when and where

it was most needed. Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery, called

his reserve "an invaluable resource in the time of greatest need." [22] The Union army faced such a "need" later that

day.

The principal Confederate attack began around 3:30

p.m. as Southern troops under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet struck the Union

left. Defending this area was the Third Corps, Army of the Potomac,

commanded by Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles. Earlier that afternoon this

flamboyant commander, in one of the most controversial decisions of the

battle, had pushed his corps between 1/4 to 3/4 of a mile forward to an

advanced and overextended position. Now, in desperation, Sickles sought

reinforcements to bolster his thin line. [23]

An ideal source from which assistance could be given

was the Artillery Reserve, for it had been created for exactly the type

of situation that now existed. Civil War artillery, though obsolete by

modern standards, could be very effective if used properly. This was

especially true when the guns could be concentrated in order to hold a

defensive position, something the Artillery Reserve could do efficiently

and rapidly. [24]

Gen. Hunt, realizing this, "sent at once to the

reserve for more artillery, and authorized other general officers to

draw on the same source." Bigelow, who had held his men in a state of

readiness, recalled that around 4:00 p.m. "an aide...rode up and asked

for reinforcements; Colonel McGilvery gave us orders" to march. A rapid

series of orders, arriving within a matter of minutes, had McGilvery

leading all four of his batteries to the support of Sickles. [25]

Charles Reed blew "Assembly" and, according to

Bigelow, "drivers mounted and within five minutes we were off at a

lively trot, following our leader to the left, where the firing was

getting to be the heaviest." Though almost all of the 1st Volunteer

Brigade, including Bigelow and McGilvery were combat veterans, the men

of the 9th Massachusetts Battery were moving into their first battle.

Quite naturally many were nervous. Yet others, probably eager and naive,

were like Reed who wrote home, "I must say I was surprised at myself in

not experiencing more fear than I did as it was it seemed more like

going to some game or a review..." Cpl. Augustus Hesse wrote home "our

Battery the 9th Mass. went in high Spirits." [26]

McGilvery lead his batteries cross-country, "skirted

fields, followed by-roads" and toward the fighting, finally arriving at

Gen. Sickles' headquarters near the Abraham Trostle farmstead. The

batteries "doubled up" and the men began to wait as McGilvery conferred

with Sickles. Bigelow described the scene:

A spirited military spectacle lay before us;

General Sickles was standing beneath a tree close by, staff officers and

orderlies coming and going in all directions; at the famous "Peach

Orchard" angle on rising ground, along the Emmetsburg Road, about 500

yards in our front, white smoke was curling up from...the deep-toned

booming of [Union] guns...while the enemy's shells were flying over or

breaking around us. [27]

|

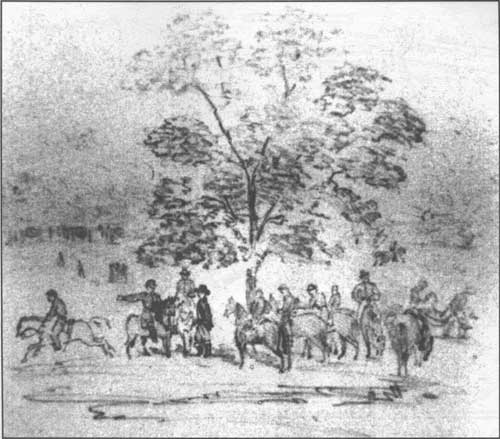

"Major General Sickles headquarters as we passed him going into

action on the 2d of July at Gettysburg. I took this sketch on the spot."

Charles Reed

(Library of Congress)

|

Sickles ordered McGilvery to examine the ground and

place his batteries as needed. As the lieutenant colonel did so, his

artillery men could do nothing but wait. Despite the shells that "were

flying over our front, or bursting in the air" the men, including the

"new and untried" soldiers of the 9th Massachusetts Battery, remained

calm. Reed, probably excited by the momentous event unfolding before him

and realizing its importance, decided to record the scene. Incredibly he

pulled out his sketch pad and began to draw. He later wrote:

at the foot of the hill... were Maj. Gen Sickels

headquarters under a tree. we halted... a few minutes giving me time to

take a scetch of him. one of his Aids was already wounded by a piece of

shell in the back and the surgeon was doing it up. [28]

In less than thirty minutes McGilvery completed his

reconnaissance and ordered up his batteries. He placed them in and to

the east of the Peach Orchard, along the left center of the Third Corps

line. It was a good choice, for the ground there served as a natural

artillery platform, being a slightly elevated plateau on three sides

(east, south and west) and having an unobstructed view in all

directions. Taking advantage of these benefits, McGilvery eventually

placed all four batteries along the Wheatfield Road, facing southward

so they "commanded most of the open country" to their front. They were,

from right to left, Capt. James Thompson's Battery C & F, 1st

Pennsylvania, Capt. Patrick Hart's 15th New York, Capt. Charles

Phillips' 5th Massachusetts and Bigelow's 9th Massachusetts. Capt. A.

Judson Clark's Battery B, 1st New Jersey Light Artillery, was already in

this same area. [29]

McGilvery also placed his batteries along the

Wheatfield Road in order to cover a dangerous 400-yard gap in the Union

line between the Peach Orchard and Wheatfield [30]

This gap existed because Sickles had overextended his line in taking up

his advanced position. Though critically important, McGilvery's decision

forced him to break a basic rule of artillery tactics. Because Civil War

artillery used direct fire, it had to be placed on the front line, thus

making it vulnerable to capture. The Artillerist's Manual of 1859

states, "Artillery cannot defend itself when hard pressed, and should

always be sustained by...infantry." McGilvery's batteries however, had

no support and could only hope they never would be "hard pressed."

McGilvery himself was probably willing to take the risk, at least

initially, for the Confederate infantry assaults at that time were

striking the extreme left of the Union line, at Little Round Top and

Devil's Den. [31]

Despite their vulnerability, all the batteries went

into position while under fire and quickly readied for action. It would

have been an impressive sight, 26 cannons and their crews, with all the

necessary equipment and hundreds of horses positioned behind the guns,

dueling with Confederate artillery nearly a mile away. Reed wrote home

that "there were five Batterys of us in a line...besides other artillery

in different positions[,] the roar of which was deafening." [32]

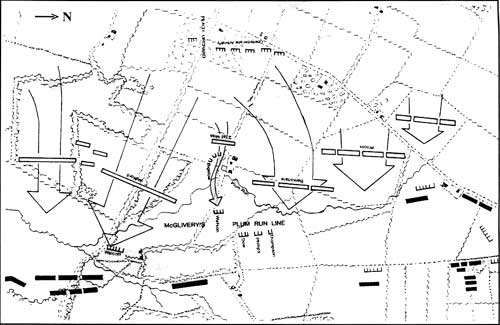

|

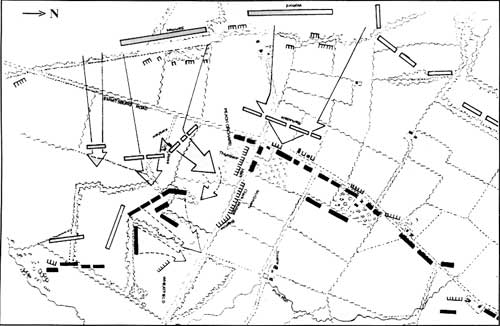

The Peach Orchard Under Attack

(Gettysburg Magazine - Morningside

Press; click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

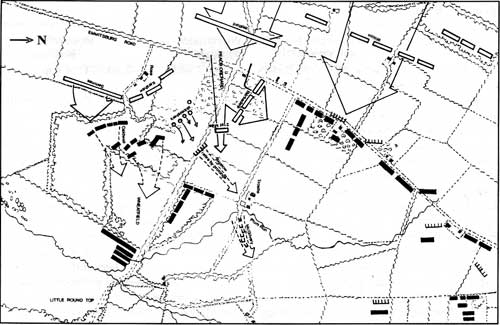

The Peach Orchard Falls

(Gettysburg Magazine - Morningside

Press; click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

McGilvery's Plum Run Line

(Gettysburg Magazine - Morningside

Press; click on image for a PDF version)

|

Upon their arrival, the primary concern for

McGilvery's men was the incoming artillery fire. One cannoneer recalled

the "position was swept by Confederate artillery fire." Bigelow

remembered, "Our position was open and exposed... One man was killed and

several wounded before we could fire a single gun..." The volume of fire

and tremendous noise were almost overwhelming. Reed, attempting to

describe it, wrote, "such a shrieking, hissing, seething I never dreamed

was imaginable, it seemed as though it must be the work of the very

devil himself." [33]

Despite being suddenly thrust into their "baptism of

fire" under such trying circumstances, the men of the 9th Massachusetts

Battery responded well, quickly preparing for action and, Bigelow

recalled, "soon covered ourselves in a cloud of powder smoke, for our

six Light Twelve guns were rapidly served..." The previous months of

drilling and strict discipline he had insisted upon now paid great

dividends. Years later Bigelow told his men, "Amid the zip of bullets,

the whiz of shot, and the explosion of shells, you maintained the

steadiness of veterans." [34]

During this time Bigelow remained active, overseeing

the actions of his men and the effect of their fire. As an example, soon

after the guns had unlimbered, "the Captain rode down the line" and

found "that a swell of ground...covered the view from my left section."

Instantly, he ordered the two guns to be limbered up and moved to the

right of the battery to open up their field of fire. [35]

Shortly after taking up its position "on that

memorable day and our battery fairly at [it]," Reed wrote that, "Captain

ordered me to the rear[,] saying there was no need of my being there."

Bigelow must have felt there was no use for a bugler with the deafening

noise. Reed obeyed "and rode back two or three rods" but then changed

his mind, as he related in a letter to his sister that, "...somehow I

coud'nt see it. I was bound to see a fight and might be of some use

after all so I disobeyed orders by turning round [and] going up to the

battery again..." [36]

It turned out to be a good decision, as Reed

explained:

I was right [to return] for presently Major

McGilvray . . . came up and set me at it in the shape of transmitting

orders from one bat 'ry to another, which suited me to a T as I had a

wider field under my eyes and could see what was going on farther to

our right and left[.] [37]

McGilvery was short on staff officers as Capt.

Nathaniel Irish, his volunteer aide, had been wounded by a solid shot

early in the fight. [38] Reed's return would also

greatly benefit Bigelow later that afternoon.

Though he spent most of time near Bigelow's and

Phillip's batteries, for it probably gave him the best vantage point,

McGilvery remained active along his entire line, overseeing the actions

of all his batteries. He attempted to concentrate his firepower "on

single rebel batteries" and claimed to have driven "five or more...in

succession from their positions." Though there is certainly some truth

in this statement, an officer in the 5th Massachusetts stated "we could

hardly tell" what effect their fire had, for thick smoke was quickly

clouding the field. The Confederates apparently had the same problem,

for Bigelow stated their fire was "so wild, that not one of their shots

was conspicuously effective." [39]

It would be fire from a different and completely

unexpected direction that caused McGilvery's command the worst problems.

Charles Reed recalled this fire, writing, "some new Batterys opened on

us a cross fire with shell and solid shot[.] their fire about this time

was tremendous." He was describing several Confederate batteries located

600 yards west of the Peach Orchard along Seminary Ridge and directly to

the right of McGilvery's line. The overshoots from these batteries were

now raking the Union guns. McGilvery reported this "enfilade fire...was

inflicting serious damage through the whole line of my command." Adding

to the frustration for the Union artillerymen was that they could do

nothing to counter this fire for, according to Capt. Phillips, "the

peach orchard was on higher ground...I could not see any of the rebels

in this direction..." [40]

This situation pointed out another major flaw in

Sickles' advanced line. Because the Third Corps line angled back at the

Peach Orchard, Sickles' front essentially faced two directions, west and

south. Thus, the converging fire of Confederate batteries could enfilade

both wings of the Third Corps line. The soldiers who would pay the price

for Sickles' mistake were the artillerymen, like McGilvery's command, to

whom the shortcomings of the position were starkly evident.

The overall situation for McGilvery's batteries, bad

as it was, suddenly got even worse. Because the Confederate infantry

assaults were being launched "en echelon" style, from south to north,

the fighting was moving closer to the Peach Orchard. McGilvery must have

sensed this for he reported "about 5 o'clock a heavy column of rebel

infantry made its appearance in a grain-field about 850 yards in front,

moving at double quick time toward the woods on our left, where the

infantry fighting was then going on." This was most likely Brig. Gen.

George T. Anderson's Brigade moving toward the Wheatfield. McGilvery

ordered the batteries to switch targets and soon a "well-directed fire"

from his batteries "destroyed the order of their march," though their

advance continued. [41]

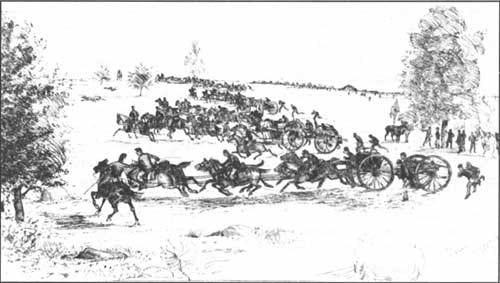

|

Charles Reed's sketch of the 9th Mass. Battery moving into its first

action, July 2, 1863.

(Library of Congress)

|

|

Charles Reed's sketch of Union artillery in action along the

Wheatfield Road. The Peach Orchard can be seen as the rise in the

distance

(Library of Congress)

|

By 5:30 p.m. "the battle...raged along the lines" as

Union troops at Little Round Top, Devil's Den and the Wheatfield were

all under attack. Near this time, McGilvery reported, "another and

larger column appeared..." He was describing the combined assault of

Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw's and Brig. Gen. Paul Semmes' brigades, as

they advanced from Seminary Ridge toward the Wheatfield. [42] At a distance of less than 400 yards these

Confederates marched directly across the front of McGilvery's batteries,

from right to left, "presenting a slight left flank." Seeing this,

McGilvery, through direct commands or through his staff (including

Reed), notified his commanders and "I immediately trained the entire

line of our guns upon them, and opened with various kinds of

ammunition." [43]

Capt. Hart, of the 15th New York Battery stated that,

"At this time my attention was drawn to a heavy column of infantry

advancing on our line. I directed my fire with shrapnel on this column

to good effect." [44]

As the range decreased the batteries switched to

canister. These shotgun-like blasts tore "great gaps or swaths" through

the Confederate ranks. Kershaw's left flank got the worst of this fire,

as one South Carolinian recalled that, "O the awful deathly surging

sounds of those little black balls as they flew by us, through us,

between our legs, and over us! Many, of course, were struck down..." [45]

All this time the batteries were also still under

Confederate artillery fire, as Charles Reed related:

I had just been along the line of batterys that

were [in] line... with an order from the Col to double shott the guns

with canister and returning a shell tore up the ground in front of my

horse at which he halted so suddenly... as to almost throw me out of the

saddle. [46]

Meanwhile, because of the heavy smoke and tremendous

noise, Bigelow was not yet aware of the advancing Confederate lines

until "Major McGilvery came to me and called my attention to...the

enemy...collecting near a house in my front."

This was the stone house and barn of the George Rose

farmstead, located about 500 yards directly in front of the battery.

Bigelow ordered the battery to open with spherical case shot and shell

which "broke beautifully" amongst the Confederate ranks.

Years later, Kershaw wrote that, "the batteries near

the orchard concentrated a terrific fire on us at that point. I well

remember the clatter of the grape [canister] against the wall of the

houses we passed." [47]

Though McGilvery's guns had done "terrible

execution," making it difficult for Kershaw's men "to retain the line in

good order," the center and right of his brigade moved steadily forward

toward the Union line in the woods to McGilvery's left front. Despite

the danger to the Union infantry in that area, Capt. Phillips ordered

his guns to keep firing, hoping "to hit the rebels without injuring our

own troops." One South Carolinian recalled, "My! how the trees trembled

and split under the incessant shower of shot and shell!" [48]

The left of Kershaw's line, somewhat disorganized

"for a short time halted about the walls and fence" near the Rose

buildings. Kershaw then ordered it, as per previous instructions, to

"wheel to the left" and attack the batteries along the Wheatfield road.

Reed, still roving along the line, remembered "down came the Rebs...from

the right behind a white fence when opposite us they left flanked and

steadily advanced on us..." [49]

McGilvery's men, now without infantry support of

their own, faced rapidly advancing and disciplined Confederate infantry.

Making matters worse was a ravine 400 yards in front of and parallel to

the Union guns, which partially hid the Confederate line. Suddenly

appearing out of the ravine, Bigelow saw them, "extending from the Rose

buildings to the Peach Orchard." Somewhat confused, the captain at first

"hesitated to open fire on them, fearing they were Sickles' men." Seeing

a Confederate battle flag, however, he quickly ordered his gunners to

fire, as did the batteries to his right. A member of the 5th

Massachusetts Battery remembered that though they "could see the rebels

fall...the gaps closed at each discharge" and the Confederate advance

continued. [50] It seemed as if the batteries would

soon be overwhelmed.

The South Carolinians closed to within two hundred

yards, when suddenly their direction of advance shifted to their right,

thus moving parallel to the artillery. [51]

McGilvery's men quickly took advantage, as Bigelow described:

. . . the Battery immediately enfiladed them with

a rapid fire of canister, which tore through their ranks and sprinkled

the field with their dead and wound, until they disappeared in the woods

on our left, apparently a mob. [52]

Though the initial Confederate assault had been

repulsed, the situation remained critical for McGilvery's batteries.

Kershaw's men quickly rallied and were "not long in taking...revenge."

Bigelow recalled that "as soon as the woods were reached, [they] sent a

body of sharpshooters against us..." Cpl. Hesse wrote: "They threw out a

heavy line of skirmishers against us..." According to Reed these men

"advanced on us giving us such a shower of small balls that it was

dangerous to be safe!" [53]

Even worse, Bigelow remembered, "At this time I saw

some Federal troops in good order move out of these very woods the enemy

had gained, and marched to the rear..." [54] Cpl.

Hesse wrote, "our Infantry gave way then...the Rebels rushed in through

the Woods," thus gaining shelter. Even worse, McGilvery reported that

the "asperities of the ground in front of my batteries were such as to

enable the enemy's sharpshooters in large numbers to cover themselves

within very short range." Thus McGilvery's line was "exposed to a warm

infantry fire" from both the front and left. Being on the far left, the

9th Massachusetts Battery received the worst of this fire. [55]

Bigelow later stated that the Confederates, having

gained "the woods, came up on my left front as skirmishers, pouring in a

heavy fire and killing and wounding a number of...my men." Private David

Brett, in a letter home, wrote that "we could hear the bullets pass

us[.] finily a man dropt about 6 foot to my right another right

behind[.] 6 men were killed within a rod of me..." Kershaw's men got so

close that one wrote, "we killed their horses with rifles easily."

Because Civil War artillery had such a slow rate of fire, even the best

gun crew could not defend itself from this type of attack without proper

support. [56]

McGilvery's gunners would not receive that support as

long as the situation to their left, in the Wheatfield, remained

unstable. With the collapse of the Union line in that area, all

available reinforcements moving toward Sickles' front were being shifted

into that area, thus depriving McGilvery of much needed support for his

guns. Near this time, Union troops from the Second Corps arrived and

launched a counterattack into the Wheatfield. The "contest was raging

hot and fierce...on our left...with desperate fighting," Bigelow

recalled, "the pendulum of battle had swung backward and forward. . ."

[57] Though this movement checked the further advance

of Kershaw's Brigade, McGilvery and his men were still without support

and under a "very annoying" musketry fire. [58]

|

Reed sketch of Lt. Christopher Ericskon and his gun crew. Erickson

was wounded earlier in the fight but refused to leave the field. The men

of Kershaw's Brigade approach from the background.

(Library of Congress)

|

These conditions continued to deteriorate until,

shortly after 6:00 p.m., the situation reached a critical point. At that

time, the growing Confederate assaults reached the salient angle of

Sickles' line at the Peach Orchard. Under the relentless advance of

the brigades of Brig. Gen. William Barksdale and Brig. Gen. William T.

Wofford, the Union line began to crumble. [59] Though

making a determined stand, the Union infantry finally began "melting

away" before the "compact mass of humanity" that Barksdale's lines

presented. This stand allowed the artillery in the orchard time to

escape, though not always in good order. [60]

This collapse also signaled the partial demise of

McGilvery's line. In order to save his guns Thompson fell back from the

orchard in some confusion. Hart's 15th New York Battery followed shortly

after due to lack of ammunition. [61] Though reduced

by half his strength, McGilvery meanwhile was keeping alert to the

approaching danger. Having no support and with his remaining batteries

threatened "from both flanks and front," he realized it was time to pull

back. [62]

McGilvery's last two batteries, Phillips and Bigelow,

were still thundering away at Kershaw's men and had not yet noticed the

danger to their right. Capt. Phillips remembered:

Fighting was going on all this time on our right,

but we were too busy to pay much attention to it until I happened to see

our infantry falling back in the Peach Orchard and a skirmish line

coming in, in front of the right of our line of batteries. [63]

This line would have been Barksdale's regiments,

advancing through the orchard after smashing the Union line located

there.

After overseeing the withdrawal of Thompson and

Hart, McGilvery next rode to Phillips and ordered him to retreat.

McGilvery's intention was to have both Phillips and Bigelow "retire 250

yards and renew their fire." He was probably hoping to reform the broken

line, or somehow stem the flow of retreating Union troops. This proved

impractical, however, as the situation was unraveling too rapidly. By

the time McGilvery reached the 9th Massachusetts Battery, he was

ordering his batteries back to Cemetery Ridge, the "natural line of

defense." [64]

Riding down his line from the right, McGilvery would

have reached Bigelow's battery last. All this time the men had been

steadily working their guns in a futile attempt to hold back the

increasing Confederate pressure from the left and front. As proof of the

battery's discipline Charles Reed, who had returned to the battery,

related "we were so intent upon our work that we noticed not when the

other batterys left..." Bigelow, however, was aware of the worsening

situation for he recalled:

Glancing toward the Peach Orchard on my right, I

saw that the Confederates (Barksdale's Brigade) had come through and

were forming a line 200 yards distant, extending back, parallel with the

Emmitsburg Road, as far as I could see... [65]

He remembered what happened next. "Colonel McGilvery

rode up, at this time, and told me that 'all of Sickles' men had

withdrawn and I was alone on the field, without supports.. limber up and

get out." [66]

Bigelow realized the order could not be carried out,

for without support and with Confederate skirmishers so close, "every

saddle would have been emptied in trying to limber up." Making a swift

decision, the captain asked McGilvery if he could "'retire by prolonge

and firing,' in order to 'keep them off.'" [67]

This bold decision revealed the confidence that

Bigelow had in his men, for to attempt such a maneuver was extremely

risky, especially with untried troops. Many obstacles and problems could

develop which could result in disaster for the battery. [68] McGilvery also must have realized the risk, but

quickly "assented [to the request] and rode away." [69] Either the lieutenant colonel trusted Bigelow or

agreed the captain had no choice.

Whatever the reason, orders were quickly given,

"prolonges were fixed" and the battery began to withdraw. It was a

movement beset with obstacles. Bigelow recalled that "No friendly

supports, of any kind, were in sight; but Johnnie Rebs in great numbers.

Bullets were coming into our midst from many directions and a

Confederate battery added to our difficulties." [70]

Furthermore, the field over which the battery

traversed contained scattered rock outcroppings and "large bowlders"

which created havoc with the alignment of prolonges, guns and limbers.

[71]

Despite all these obstacles, however, the "Battery

kept well aligned in retiring," and moved steadily back "with a slow,

sullen fire." Facing two different and distinct threats, Bigelow dealt

with each differently. He recalled the battery "withdrew—the left

section keeping Kershaw's skirmishers back with canister, and the other

two sections bowling solid shot towards Barksdale's men." [72]

Two of the most important factors which made this

retreat successful were the discipline Bigelow had instilled into his

command, and (as McGilvery earlier termed it) the "control of an

energetic bold leader." Bigelow and his officers provided that necessary

leadership, which the enlisted men recognized. Charles Reed recalled,

"we are proud of all of our officers[,] they were constantly in the

thickest of the fighting[.]" In his official report, McGilvery noted

that Bigelow "evinced great coolness and skill in retiring" his guns.

[73]

After leaving Bigelow, McGilvery had galloped toward

the rear in order to regroup and reorganize his other batteries along

Cemetery Ridge. Just after splashing across Plum Run and reaching the

higher ground beyond, however, the lieutenant colonel was probably

shocked by the situation that confronted him. Expecting to find

infantry onto which he could rally his batteries, McGilvery instead

discovered that the Third Corps "had left the field" and Cemetery Ridge

was "fearfully unprotected." This dangerously wide 1,500 yard gap, from

the foot of Little Round Top to the left of the Second Corps, was only

lightly defended by a few scattered and bloodied units. The artillery

officer knew that, if the gap was discovered by the rapidly advancing

Confederates, disaster might result for the Union army. In his official

report McGilvery described the situation succinctly, writing, "The

crisis of the engagement had now arrived." [74]

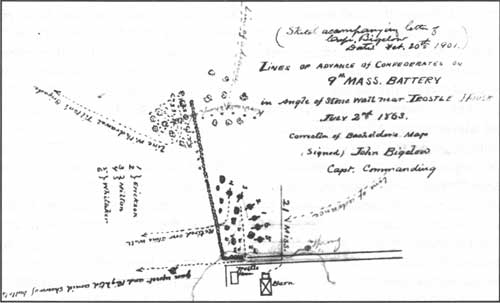

|

John Bigelow sketch of the position of his guns during their final

stand at the Abraham Trostle house.

(Library of Congress)

|

Somehow, a new line must be established to close the

gap. Yet, because of the numerous obstacles he faced, that task seemed

an impossibility. The primary difficulty was that the only units

available to McGilvery were his own damaged and worn gun crews and other

batteries retreating through the area. Again, the artillery would stand

alone. [75]

Making matters worse was that since McGilvery would

rally the last batteries to retreat, they would be in the worst shape.

He also would have very little assistance, as his staff had dwindled

during the battle. Having barely digested this information, McGilvery

also realized he needed to act quickly, for the Confederates were fast

approaching.

It was here that McGilvery's similar experiences at

both Cedar Mountain and Second Manassas paid dividends, for, despite the

overwhelming odds, the artillery officer clearly understood that

drastic measures were necessary. The bold decisions he soon undertook

proved he was "determined to sacrifice his Batteries, if necessary, in

an effort to stay the enemy's advance into the opening in the Lines..."

[76]

The lieutenant colonel immediately proved this last

sentiment, for a means of buying more time was suddenly presented to

him. He spotted the 9th Massachusetts Battery, which had just halted

under cover of a slight knoll near the Trostle farmstead and was

beginning to limber up in preparation for retreat. Without hesitation,

McGilvery spurred his horse, galloping "alone, in the midst of flying

missiles" toward the battery. Luckily, he came through this fire

unscathed, though his horse staggered, being "shot four times in the

breast and fore shoulder." Indeed, Bigelow recalled the animal was

"riddled with bullets," yet somehow managed to keep going. McGilvery

finally reined up in front of the captain and gave him new orders:

Captain Bigelow, there is not an infantryman back

of you along the whole line which Sickles' moved out; you must remain

where you are and hold your position at all hazards, if need be, until

at least I can find some batteries to put in position and cover

you. [77]

Having received this command himself, McGilvery knew

the consequences of these orders. So too did Bigelow, who later wrote

"the sacrifice of the command was asked in order to save the line." The

full implications probably stunned the captain, who only managed the

weak reply of, "I would try to do so." [78]

The men of the battery were probably stunned as well.

A moment before Bigelow had ordered them to limber up, "hoping to get

out and back to our lines before" the Confederates "closed in on us."

Having just survived an intense "baptism of fire," including performing

extremely risky and difficult maneuvers, they probably felt incredibly

lucky just to be getting away. Now, an officer they had known barely a

week had literally ordered their destruction. It was a complete

reversal of the hopes the men held, moments before, of escaping. Charles

Reed stated simply, "we were left in a critical position[.]" [79]

Bigelow found himself, like his commander had a few

moments before, in a "position... which...was an impossible one for

artillery." He later wrote:

The task seemed superhuman, for the knoll already

spoken of allowed the enemy to approach as it were under cover within 50

yards of my front, while I was very much cramped for room and my

ammunition was greatly reduced. [80]

Even worse, with the enemy quickly closing in, the

battery was trapped in the angle of two stone walls, making retreat

impossible. Furthermore, they were still without support, and the men

were reaching total exhaustion, as Cpl. Hesse related, "the blood run

all over me[.] I was Sweting and the Powder of handling the Cartrige and

Smoke blacked my face... so if you had seen me you would not have Known

me." [81]

Under such circumstances, it would not have been

surprising for a green unit, such as Bigelow's battery, to simply

disintegrate in panic upon receiving such orders. Yet the men of the 9th

Massachusetts Battery did the opposite. As McGilvery rode back to pull

together his new line, Bigelow ordered his men to prepare for action,

and they immediately obeyed. Their reasons reveal much about their

commander, and the men themselves.

Primarily, the men obeyed because of discipline and

leadership. The discipline, which had been instilled by Bigelow through

months of drilling and strictness of military regulation, was about to

reap significant benefits for them on this small Pennsylvania farmstead.

Also, "the self-possession to stand alone," which the captain had

received at Harvard, gave him the ability to provide the cool-headed

leadership that his men required. Bigelow would be the "energetic bold

leader" McGilvery needed at that critical moment. [82]

Another important reason why the battery stood its

ground was the character of the men themselves. Most were just like

Charles Reed who, though from common origins, were, according to

Bigelow, "Without exception... soldiers only from the highest sense of

duty" and they fought for a cause in which they firmly believed. Though

earlier given a chance to safely leave the fight, Reed just "could'nt

see it," and had "disobyed orders" by returning to his battery. Cpl.

Hesse best summed up the feelings of all the men in the battery when he

later proudly wrote, "We, the Glorious-young 9th Mass-Battery in

Splendid Organization and for the first time in an engagement - stood

the ground and were Willing to die for the Contry." [83]

Realizing desperate circumstances required desperate

actions, Bigelow took chances. Risking the danger to his own men, the

captain ordered all the ammunition laid beside the guns for "rapid

firing." Utilizing every means possible to slow the advancing

Confederates, he then ordered his four guns in the center and right, to

"commence...firing solid shot low, for a ricochet over the knoll" and

into the infantry beyond. With his six pieces loaded and arranged in a

semicircle, with the limbers and horses crowded into the corner of the

stone walls, the battery soon fell silent to await the onslaught. Though

"the moments seemed like hours," Bigelow recalled the preparations were

completed "not a moment too soon... for almost immediately the enemy

appeared over the knoll." [84]

Bigelow described the desperate action that

followed:

Waiting till they were breast high, my battery was

discharged at them every gun loaded. . . with double shotted canister

and solid shot, after which through the smoke [we] caught a glimpse of

the enemy, they were torn and broken, but still advancing... [85]

These tenacious troops were the approximately 400

men of the 21st Mississippi Infantry (Barksdale's Brigade), which struck

the right and front of the battery. At the same time skirmishers from

Kershaw's Brigade, who had doggedly followed Bigelow's guns, threatened

from the left front. [86]

Despite the battery's terrible fire, Bigelow recalled

that, "...the enemy opened a fearful musketry fire, men and horses were

falling like hail... Sergeant after Sergt., was struck down, horses were

plunging and laying about all around..." [87]

Flushed with victory, the Mississippians pushed

onward, "yelling like demons," as "Again and again they rallied."

Bigelow remembered, "The enemy crowded to the very muzzles [of the guns]

but were blown away by the canister." Because of his men's steadiness,

the captain could later proudly claim, "Notwithstanding their insane,

reckless efforts not an enemy came into [the] battery from its front."

[88]

As this struggle continued, however, the situation

grew worse for the battery. Bigelow recounted how the "rapid fire

recoiled the guns into the corner of the stone-wall," which "more and

more cramped my position." As ammunition began to run low Bigelow,

still willing to take risks, ordered case shot fired with the fuzes cut

short "so that they would explode near the muzzle of [the] guns."

Lastly, though the battery's front was secure, the Confederate "lines

extended far beyond our right flank," the captain wrote, "and the 21st

Miss.,...swung without opposition and came in from that direction, pouring

in a heavy fire all the while." [89]

Now caught in a "withering cross fire," and with his

left section "entangled among some large bowlders" and the stone wall,

Bigelow ordered those guns to retire. After quickly limbering up the

crews headed for their only escape, an opening in the stone wall

opposite the Trostle farmyard. The first gun, however, upon reaching

the gateway, overturned and blocked it. While the men of this gun

scrambled to right it, the crew of the trailing gun looked in

desperation for a way out. A few men "tumbled the top stones off the

wall" before the drivers headed "directly over the wall." Reed

remembered the "horses jumping and the gun...going over with a tilt on

one side and then a crash of rocks and wheels" as the piece made its

successful flight. [90]

Knowing the end was drawing near, Bigelow gave orders

for the remaining crews to prepare for a general retreat and "rode to

the stone wall, hoping to stop some of [the] cannoneers and have them

make a better opening, through which I might rush one or more of the

remaining four guns..." But with the left section gone, Kershaw's

skirmishers "being unchecked, quickly came up on [the] left and poured

in a murderous fire." Bugler Reed, at his captain's side, recalled "I

saw the enemy skirting down the stone wall...and called to the captain

to look out," while at the same time "throwing his horse back on his

haunches." Bigelow never heard the warning as six skirmishers opened

fire and the captain "caught two bullets, my horse two, two flew wide."

[91]

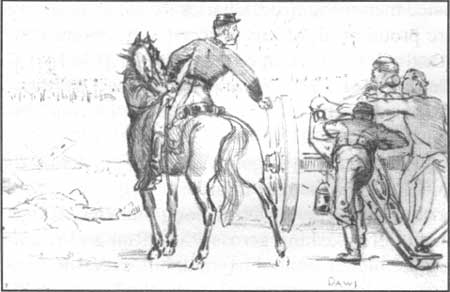

|

Reed's sketch of his act of heroism in saving Capt. Bigelow at

Gettysburg. Reed was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions.

(Hall's Regiments and

Armories of Massachusetts...)

|

As his horse staggered to the rear the captain fell

near the wall, dazed. Reed and Bigelow's orderly were quickly by their

commander's side. As he "drew himself back to the stone wall" Bigelow

recalled seeing "the Confederates swarming in on our right flank."

Hand-to-hand fighting engulfed the battery as the men began to use

handspikes and rammers in order to defend their guns. [92]

With all the remaining officers and most of the

sergeants also killed or wounded, "the air. . .alive with missiles," and

the battery caught in a turmoil of confusion, the resistance of most

units would collapse. Once again, however, the men of the 9th

Massachusetts Battery did not flinch. Instead they stood to their guns,

their discipline holding them together. Private David Brett wrote that,

"We fought with our guns until the rebs could put heir hands on [them] .

. .the bullets flew thick as hailstones. . .it is a mericle that we were

not all killed...not a man run[,] 4 or 5 fell within 15 feet of me..."

[93]

Bigelow also noticed that some Confederates were

"standing on the limber chests, and shooting down cannoneers." Yet, the

captain proudly noted that "Not even then did the batterymen cease their

fire." [94]

Bigelow realized that "Longer delay was impossible,"

and "Having thus accomplished what was required of my command," he gave

the order to retreat. It was only at this point that the men abandoned

their pieces and made their way to the rear. They had sacrificed

themselves as ordered, having lost three of four officers, six of eight

sergeants, 19 enlisted men, 88 horses and four of their six guns. Yet

this incredible stand had "delayed the enemy 30 precious minutes." [95]

Though shattered, the battery had not sacrificed

itself in vain, for Bigelow, "glancing anxiously to the rear... saw the

longed for batteries just coming into position." McGilvery's new line

was nearly completed. In a large part this was possible because of the

time that Bigelow and his men had so dearly bought. [96]

In the midst of this chaos, as the men "scattered" to

the rear, Reed remembered his wounded captain "told...the orderly and

myself to leave him and get out as best we could." The bugler, however,

"didn't do just that." Instead Reed, as he had earlier in the battle,

disobeyed orders. Years later Bigelow described the actions of his

faithful bugler:

...he remained with me...called my orderly and

had him lift me on to his horse; then taking the reins of both horses in

his left hand, with his right hand supporting me in the saddle, took me

at a walk [to the rear]. [97]

Reed recalled what happened next:

Then we tried to get away Some of the confederates

saw us...and several of them tried to take us prisoners. They did not

fire at once, but tried to pull us from the horses' backs, but were

unsuccessful, as the horses kicked and I was able to do some execution

with my...saber... We were still struggling when an officer, who saw his

men were about to fire, told them not to murder us in cold blood. Then I

started for the northern forces. [98]

Those forces were part of McGilvery's new artillery

line, waiting to open fire. The wounded captain and his bugler were now

between the battle lines, with "the shells of the Enemy...breaking all

around us." They had over 400 yards of open ground to cross before

reaching safety. "Before I was halfway back," Bigelow remembered an

officer was sent "urging me to hurry, as he must commence firing." The

captain's painful wounds, however, prevented the horses from moving at

anything faster than a walk, so Bigelow told him to "fire away." Now

caught between the fire of both lines, Reed also had to contend with the

orderly's horse, which had become frightened and difficult to control.

Bigelow later praised Reed's conduct, writing:

Bugler Reed did not flinch; but steadily supported

me; kept the horses at a walk although between the two fires and guided

them, so that we entered the Battery between two of the guns that were

firing heavily... [99]

Reed's actions are proof of the loyalty and respect

Bigelow had earned from his men. Less than four months earlier Reed had

labeled his commander "a regular aristocrat," feeling he was worse than

a slave owner. Yet at Gettysburg the bugler had twice disobeyed orders

and willingly risked his life to save his captain. Bigelow never forgot

Reed's "gallantry," writing to him thirty-two years later that "the

obligation still remains with myself." [100]

Bigelow felt so strongly about this that in 1895 he

submitted Reed's name for a Medal of Honor, citing his "distinguished

bravery and faithfulness to duty at the Battle of Gettysburg." When the

medal was awarded later that year Bigelow stated "I feel the Government

honors itself in honoring you." [101] On a more

personal level, Bigelow felt Reed had not only saved him from a stint in

a Confederate prison but, more importantly, had also saved his life. The

captain later wrote, "Even though the Mississippians would probably have

spared me, Dows (6th Maine) searching canister and Shells would not have

done so." [102]

The 6th Maine Battery, commanded by Lt. Edwin B. Dow,

was one of six full or partial batteries that formed McGilvery's new

artillery line. During the time that Bigelow and his men sacrificed

themselves at the Trostle farmstead, the lieutenant colonel had been

scrambling to cover the dangerous gap in the Union lines. This patchwork

line of guns was located along a small ridge situated just east of Plum

Run, and hence became known as the "Plum Run line." [103]

Working almost entirely unassisted and being "the

only field officer" in the area, McGilvery had, with or without orders,

assumed increased authority. As an example, McGilvery was probably

delighted when his old command, the 6th Maine Battery, unexpectedly

arrived from the rear. Lt. Dow reported that "McGilvery ordered me into

position...remarking that he had charge of the artillery of the Third

Corps." Thus, he commandeered every available gun he could muster, and

"by his personal effort alone" completed the semblance of a line by the

time Bigelow's battery was overrun. [104]

The line was weak, varying between six to seventeen,

and possibly twenty-three guns. His initial line consisted of, from left

to right, four guns of Lt. Melborne Watson's Battery I, 5th U.S

Artillery, Dow's four guns, three from Phillips' battery and two from

Thompson's. The strength of the line would constantly change, however,

as new batteries arrived and others retired to the rear. [105]

The lieutenant colonel's earlier statement concerning

the value of discipline and bold leadership enabling a small body of

men to hold off twice their number seemed prophetic at this moment, and

was certainly put to the test. McGilvery needed all the "coolness and

rapidity of thought and action" he possessed, for few artillery officers

faced a more "critical" moment. [106]

The "Plum Run Line" faced two distinct threats: three

complete or partial infantry brigades, and Confederate artillery which

had positioned itself in the Peach Orchard area, approximately 1,500

yards to the west. The most dangerous threat was obviously the

approaching infantry, so McGilvery directed his batteries to concentrate

on them. Lt. Dow reported:

On going into position my battery was under a

heavy fire from two batteries of the enemy. . .I replied to them with

solid shot and shell until the enemy's line of skirmishers... came out

of the woods to the left front of my position and poured a continual

stream of bullets at us. I soon discovered a battle line of the enemy

coming through the woods, about six hundred yards distant, evidently

with a design to drive through and take position of the road to

Taneytown, directly in my rear. I immediately opened upon them with

spherical case and canister . . . Their artillery, to which we paid no

attention, had gotten our exact range, and gave us a warm greeting.

[107]

Despite their best efforts, the situation appeared

grim for the artillery crews. The 21st Mississippi Infantry, soon after

capturing Bigelow's guns, regrouped and charged McGilvery's line, making

Lt. Watson's Battery I, 5th U.S. Artillery their target. The regulars

"poured canister, some twenty rounds" into the approaching

Mississippians, before coming under a killing musketry fire. Watson was wounded

and so many of his "men and horses were shot down or disabled...that the

battery was abandoned." [108]

Lt. Dow reported that, "It was evidently their

intention, after capturing. . .Company I, Fifth Regulars, to have

charged right through our lines to the Taneytown road, isolating our

left wing and dividing our army." [109]

The situation seemed hopeless indeed, when at one

point the total strength of McGilvery's line dwindled to just six guns,

as various batteries ran out of ammunition or where overrun. [110]

"This was the hour," stated one historian, "when

McGilvery's genius as an officer of artillery shone brightest." During

this emergency, he remained active along his line, directing fire,

shifting batteries for maximum effect and seeking reinforcements. He

repeated his earlier "hold at all hazards" order to several battery

commanders during this crisis. [111]

McGilvery's efforts paid great dividends, for he was

able to slow the approaching Confederate lines. One veteran recalled

Barksdale's ranks, "Thinned by the storm which swept down with such

terrific fury from the ridge, the advance line staggered and began to

waver." Even Wilcox's Alabama Brigade, facing the right end of

McGilvery's line, was effected by this fire. Wilcox reported the

situation when his men reached the swale created by Plum Run. "Beyond

this, the ground rose rapidly for some 200 yards, and upon this ridge

were numerous batteries of the enemy... From the batteries on the

ridge...grape and canister were poured into our ranks." [112]

This fire, combined with the previous losses the

Confederates suffered, slowed the disorganized Southern brigades.

McGilvery also took advantage of the growing darkness, smoke, confusion

and terrain to halt them along Plum Run. In his official report, Lt. Dow

stated, "...owing to the prompt and skillful action of [Lt. Col.]

Freeman McGilvery" the Confederates were "foiled, for they no doubt thought

the woods in our rear were filled with infantry in support of the

batteries, when the fact is we had no support at all." [113]

For over an hour, in the increasing twilight,

McGilvery's thin line covered the dangerous gap along Cemetery Ridge,

eventually accomplishing exactly what he had intended. Infantry

reinforcements began to arrive, narrowing and then finally

reestablishing the battle line. [114] By 8:00 p.m.,

the fighting having sputtered to a bloody conclusion, McGilvery was able

to pull back and reorganize his battered and damaged batteries. [115] McGilvery must have realized immediately the near

miracle he and his artillerymen had accomplished that day. Later that

month he wrote, "at Gettysburg...I believe I did as much as almost any

Officer to save our army from a defeat on the 2d of July..." [116]

On a personal level, McGilvery received numerous

compliments from superior officers, including Brig. Gen. Hunt, who

wrote, "I could not ask for more efficiency or devotion than you

displayed..." The best compliment of all, however, probably came from

one of McGilvery's subordinates, Capt. John Bigelow, when he later

wrote:

Without an aide or an orderly . . . he was the

only field officer who realized and tried to remedy the situation. He

was fearless, having his horse shot several times, and was untiring in

keeping the enemy from discovering the ever widening and unprotected

gap in our lines...He gave new courage to the officers of these

[batteries] and placed and maneuvered them... in many different

positions, checking every advance... [117]

Even the enlisted men, whom McGilvery commanded that

day, recognized the significance of their actions. Cpl. Hesse wrote,

"I...fought and done all what...was in my power to keep the Rebels back,

and to have Victory on our Side." Charles Reed, in a letter written just

seven days later, wrote, "we saved the line from being broken..." [118]

The artillery branch of the Army of the Potomac had

indeed made a tremendous contribution to the Union cause on July 2,

1863. Union batteries, despite the extremely adverse conditions in which

they were positioned, including lack of proper support, and under

tremendous pressure, had assisted in turning back numerous Confederate

assaults.

Many factors contributed to this success. One of the

most important was the officers, such as Freeman McGilvery and John

Bigelow. Using their guns for maximum effect, including the willingness

to sacrifice units if necessary, along with the cool-headed leadership

they exhibited, enabled them to hold the batteries together during this

crisis. Another factor was the enlisted men themselves. Soldiers like

Charles Reed, whose courage and discipline allowed them to perform

beyond expectations.

Though the direct association of these three men

lasted less than six months, they had made a difference at Gettysburg.

The fortunes of war, however, held a different fate for each.

Charles Reed served with the 9th Massachusetts

Battery until November 1864, when he was detailed to the topographical

engineers, the army at long last taking advantage of his artistic

ability. The war allowed Reed to improve his talent, for he established

himself as a well-known artist upon his return to Boston. His

illustrations appeared in the Boston Globe, and in numerous

books, such as Hard Tack and Coffee and Battles and Leaders of

the Civil War. Reed's drive enabled him to continue working well

into his early 80's, just two years before his death on April 24, 1926.

Throughout his life, the one-time bugler also managed to stay in touch

with his former commander, and then friend, John Bigelow. [119]

Bigelow eventually recovered from his Gettysburg

wounds and returned to the battery later that summer. He led it through

numerous actions during the fall campaign of 1863, the Overland Campaign

of 1864, and during the siege of Petersburg, eventually being brevetted

to major for "gallantry." He fell ill in the fall of 1864, however, and

was discharged for disability on December 31. His farewell order to the

battery, summed up his attitude on what made them "veterans, who have

won an enviable name." This reputation, he reminded them, was earned

through "strict discipline and ready obedience." [120]

Bigelow also benefitted from his military service,

for his post-war career, though far less glamorous, was highly

productive. In Boston he was elected to the State Legislature and later

worked as an inventor in New York City, Philadelphia, and finally

Minneapolis. [121] The former artillery officer also

authored two books before his death in 1917. Not surprisingly, The

Peach Orchard (1910) and Supplement to Peach Orchard (1911),

both dealt with the role of artillery at Gettysburg. These writings not

only reveal the hold the battle had on the former officer, but also the

lack of recognition his arm of service had received in the post war

years.

Both books were written in objection to a decision of

the War Department's Battlefield Commission to name a new avenue, which

passed through the area of McGilvery's "Plum Run Line," "United States

Avenue." Bigelow quite naturally felt this was an insult to the men, and

service, of the artillery who struggled in that area. He petitioned for

the new road to be named "McGilvery" or "Hunt Avenue," feeling the

"Artillery Corps, through its Commander, is entitled to a prominent

Battle Avenue." [122]

Bigelow's writings were also an attempt to give his

former commander the proper credit he rightfully deserved.

Col. Freeman McGilvery of Maine, Commander First

Volunteer Brigade, Artillery Reserve, Army of the Potomac, was one of

the real heroes of the battle of Gettysburg...McGilvery, with his

Artillery alone, stayed the advancing enemy and prevented their

discovery of the opportunity offered for success. This feat of arms,

requiring the sacrifice of many lives and the wounding of many men, we

believe should be recognized and honored... His Comrades and his State

may well demand, that his services... receive some proper

recognition. [123]

Indeed, Freeman McGilvery's status seemed to be on

the rise after Gettysburg. He continued to command a brigade in the

Artillery Reserve until May, 1864, and then took command of the army's

artillery park and train, which he lead through the Overland Campaign

and during the early stages of the siege of Petersburg. On August 9,

1864, he was promoted to Chief of Artillery, 10th Army Corps, commanding

fifteen batteries. [124]

A cruel fate, however, would tragically cut short

McGilvery's promising military career. On August 16, while overseeing

his batteries during the engagement at Deep Bottom, he was slightly

wounded in the left forefinger. Being faithful to his duties though, he

remained at his position throughout August, during which "his labors

were unremitting." Not surprisingly the wound did not heal properly and

on September 3 McGilvery consented to surgery. During this seemingly

simple operation, however, McGilvery "died suddenly... from the effects

of chloroform taken during amputation of [his] finger..."[125]

Freeman McGilvery never lived long enough to see a

"History Written Truthfully" concerning the Battle of Gettysburg. His

untimely death it seems also sadly diminished the chance for proper

recognition of his services, not only at Gettysburg, but on countless

other battlefields. That fact is clear if one visits the Gettysburg

battlefield today and examines the site of McGilvery's heroic stand

along the Plum Run swale on July 2, 1863. There, a cast iron sign

identifies the road passing through that area. It simply reads "United

States Avenue."

To all the men who served in the Union artillery at

Gettysburg, it seems their fate was to be "unsung heroes." Despite the

sacrifice, courage and devotion of soldiers just like McGilvery, Bigelow

and Reed, "History" has accorded them a secondary role in the battle. In

a larger sense, however, what future glory or recognition they would

receive meant nothing to these men during the war. What they had lost

was foremost in their minds. Not only their comrades, but also their

innocence. The war had changed them forever. Charles Reed related this

fact in a letter home, when he wrote:

During the din of battle my feelings were curious

and various but the one idea I entertained could not be shaken off until

the fight had ceased for the day it appeared to be a grand terrible

drama we were enacting and the idea of being hit or killed never

occurred to me, but when I saw the dead, wounded, and mutilated pouring

out their lifes blood. . . then the terrible sense of realty came upon

me in full force. the novelty had vanished I could only turn my thoughts

to him who sees and controls all, with silent thanks giveings and weep

for the many many dead and maimed. [126]

NOTES

The author wishes to thank the

following individuals and is grateful for the invaluable assistance

rendered in the research for this paper: Lee Harrington, Roy Frampton,

Michael Snyder, Jeffrey Stocker, Jim Clouse, and Tom Desjardin.

1 Freeman McGilvery to Gov. Abner

Coburn, July 20, 1863, 6th Maine Battery Correspondence, Records of the

Adjutant General, Maine State Archives (hereafter cited as MSA).

2 Adjutant's General's Report, 1865,

MSA, 420-1. McGilvery was born in Prospect (now Stockton) Maine on

October 29, 1823. He began sailing at age 18 and by the age of 21 was a

captain.

3 Ibid., McGilvery to Gov. Israel

Washburn, October 25, 1862, MSA.

4 Bvt. Brig. Gen. Charles Hamlin,

"Historical Sketch of Sixth Maine Battery," Maine at Gettysburg,

Report of Maine Commissioners (Portland, ME: Lakeside Press, 1898),

334-6; McGilvery to Washburn, August 16, 1862, MSA.

5 Ibid., 336-7; U. S. War Department,

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of

the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D. C.: Government

Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, Vol. XII, Part 2, 419-20

(hereafter cited as OR; all citations are from Series I). One of

McGilvery's soldiers claimed the battery had fired the last shot of the

battle (see "Recitals and Reminiscences," National Tribune,

August 1, 1909).

6 Freeman McGilvery Military Service

Record, National Archives. Though McGilvery was informed of his

promotion in February, it was not made official until April 3.

7 Maine at Gettysburg, 337-9;

OR, Vol. XXV, Pt. 2, 471-2.

8 Freeman McGilvery Military Service

Record, NA; Henry Hunt to John Bachelder, John B. Bachelder Papers, New

Hampshire Historical Society (photocopy in GNMP Library); hereafter

cited as Bachelder.

9 Lee Harrington, "John Bigelow, from

Harvard to Gettysburg," unpublished paper, University of Massachusetts,

Boston, May 1994, 5, 9-10.

10 Ibid., 10-15.

11 Ibid.

12 OR, Vol. XI (2), 268; J.P.C.

Winship, Historical Brighton, Vol. I (Brighton, Massachusetts:

George A. Warren, 1899), 53-4.

13 Harvard College, 1861-1892, Fifth

Report, New York, 1892, 9; Levi Baker, History of the Ninth

Massachusetts Battery (South Framingham, Massachusetts: Lakeview

Press, 1888), 44 (hereafter cited as Baker, Ninth); John Bigelow

to Gov. John Andrew, February 9, 1863, Executive Department Letters

Received, Governor's Correspondence, Vol. 94, Massachusetts State

Archives, Boston.

14 Baker, Ninth, 45; Frederick

H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (Des Moines:

Dyer Publishing Co., 1908), 1245.

15 Bigelow, The Peach Orchard,

62; Charles W. Reed letter to sister Helen, March 9, 1863, Box 4,

"Charles Wellington Reed Collection," Manuscripts Department, Library

of Congress, Washington, D.C. (hereafter cited as Reed Collection,

LC).

16 Charles Winslow Hall, ed.,

Regiments and Armories of Massachusetts, An Historical Narrative of

the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (Boston: W. W. Potter, Co.,

1901), 553; Rough draft of Reed family history, "Charles Reed

Collection," LC; Jacob Whittmore Reed, History of the Reed Family in

Europe and America (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1861), 470; 1860

Federal Census, National Archives, Washington. Though Joseph Reed did

not die until 1868, the records seem to indicate that he and his wife

did not reside in the same household throughout much of Charles'

childhood. Also, throughout the war, Charles Reed wrote over 120

letters, all of them addressed to his mother and sisters, not one to his

father. Nor is Joseph Reed even mentioned in these letters.

17 Charles W. Reed Military Service

Record, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Charles Reed Papers, LC;

Reed to sister Helen, July 2, 1862, Reed Collection, LC.

18 Reed to sister Helen, March 9,

1863, Reed Collection, LC.

19 "Letter, Order, Descriptive Book,

Ninth Massachusetts Battery," NA; Baker, Ninth, 45; Reed to

sister Helen, March 9, 1863, Reed Collection, LC.

20 Baker, Ninth, 46.

21 OR, Vol. XXVII, Pt. 3, 972;

John W. Busey and David Martin, Regimental Strengths and Losses at

Gettysburg (Baltimore, MD: Gateway Press, Inc., 1982), 114.

McGilvery's brigade consisted of four batteries: 5th Massachusetts