|

IF YOU SEEK HIS MONUMENT, LOOK AROUND:

E.B. Cope and the Gettysburg National Military Park

by Thomas L. Schaefer

So who was he and what did he do at

Gettysburg?

Questions like these naturally arise when scanning a

list of "The Unsung Heroes of Gettysburg." And a certain skepticism

about the propriety of E. B. Cope's inclusion on this list might also

naturally arise when reading that he was one of Brigadier General

Gouvenor K. Warren's topographical assistants and that, most probably,

he never fired a shot while on the field.

Then what on earth makes Cope a hero?

I suppose one may reasonably challenge the premise

that Cope is an unsung hero, especially when combatants like brigade

commander George Sears Greene and artillerist John Bigelow have yet to

receive the full attention due them. And I suppose one may also question

if Cope's contributions were truly as noteworthy as those of the 2nd

Virginia's ever-fluid skirmish line who kept units of two Union corps in

check, or of George Doles' very attentive file closers who drove their

companies to a stunning victory on 1 July. Succinctly, yes Cope's

contributions were that noteworthy. We merely need to expand our

concept of what a hero is and then be willing to explore some different

perspectives.

|

Emmor Bradley Cope

(Chester County (NY) Historical Society)

|

We will find that Emmor Bradley Cope was a

multi-faceted person whose contributions at Gettysburg were numerous and

diverse, for Cope essentially directed the physical creation of

the Gettysburg National Military Park. He designed significant elements

of its landscape and its infrastructure (i.e. walls, gun carriages,

monuments, towers, etc.); and as we drive the roads Cope helped create

and view the spaces we struggle to understand, we should be aware that

Cope's work and persona shaped nearly all of what we respond to

viscerally, spiritually, and academically. Perhaps we cannot really

understand "what they did here" until we understand what Cope and the

Battlefield Commission did here. And that is this essay's gist.

After examining some philosophical and theoretical

issues, I'll outline Cope's background, describe some of his

contributions and interweave some perspectives of what it all might mean

to us and to the continuing study of the battle. We'll first see Cope as

a symbol, then as a man; and as his life, talents, and efforts become

evident, I trust you will embrace E. B. Cope as one of Gettysburg's

truly unsung heroes, and that as a student of the field, you will be

persuaded to attach more significance to the phrase "what on earth" and

be encouraged to "see" Gettysburg in a different, more holistic, or

inclusive manner.

We first need to understand the type of hero Cope

was, before we can fully appreciate the significance of his actions. We

can also then appreciate that Cope can serve as a symbol of us all, and

as such, he is linked to hallowed ground which is significant to us all.

(Even Abraham Lincoln once had a few words to say about that.)

Our sense of what heroes are - especially ones with

military association - is usually derived from the classical models:

heroes are mythic demi-gods possessing great strength; they are cunning

and courageous, and are nobel, fearless, and worthy of worship. Heroes

like these can be easily named. They include Hercules, George

Washington, John Wayne, and, more recently, Joshua L. Chamberlain,

colonel of the now-famous 20th Maine, and featured figure in Michael

Shaara's novel, The Killer Angels and Ted Turner's movie

"Gettysburg."

When we broaden our vision of heroes to include Noah

Webster's third definition, we find they can be "any person admired for

his qualities or achievements and regarded as an ideal or

model." [1] If we were to further expand our vision by probing

into the anthropological and philosophical meaning of heroes, we would

quickly find ourselves confronted by a host of figures evoking complex

meanings and values; and that would pull us toward somewhat esoteric

issues like being (ontology) and transcendence (metaphysics).

[2] And while that is no place to journey when writing

about a topographic engineer, it is necessary for us to take a few steps

down that path, for ultimately, I would like you to view Cope as an

heroic symbol called Everyman who toiled within the broader context of

one of America's most famous and most studied symbolic landscapes.

The French philosopher Albert Camus addressed Cope's

variety of heroism (Webster's third definition) in his essay on the

eternal strivings of the Greek mythological figure Sisyphus. Camus

viewed Sisyphus as Everyman - that composite individual who embodies all

that is typical of and all that is experienced within the human

condition. Many of you have seen Sisyphus' trials transformed into a

desk ornament for over-burdened people. Sisyphus was an impudent

individual who defied the gods and was therefore sentenced to an

eternity spent pushing a huge boulder up a huge mountain, only to have

it roll from his grasp a few feet from the summit. (We've all

experienced frustrations like that, haven't we?) Camus labeled Sisyphus

the "proletarian of the gods" (he meant "working class stiff") and

drearily noted "the workman of today works every day in his life at the

same tasks." [3]

It is not my intent to classify Cope's heroism as

drudgery, but rather to illustrate its type while also providing a point

of perspective concerning its duration and endurance. For instance, at

Gettysburg heroic events in the classic sense are mostly measured in

seconds, minutes, or hours, i.e. the mortally wounded Alonzo Cushing

firing one more canister charge into Pickett's men, the 1st Minnesota's

desperate plunge into Wilcox's overwhelming numbers, or the hellish

fighting on Culp's Hill that raged for more than six hours. [4]

In comparison, we will find that E. B. Cope's actions at Gettysburg

spanned decades, and he was heroically consistent in their

execution.

If we now appreciate that Cope's persona - the total

of all that he was - consisted of elements of Everyman and Sisyphus

blended together with his innate characteristics and abilities, and that

his type of heroism is grounded upon the premise that the actions of

talented, yet common people can be elevated to noble standards through

skill, the striving for excellence, and unflagging effort, then we may

next identify exactly what it was at Gettysburg that Cope did. Like much

in life, the answer is simultaneously simple and complex. But,

basically, E. B. Cope devoted more than thirty years (1893 - 1927) to

overseeing the creation of a great American symbol.

As we know, symbols are things within a culture that

are commonly understood to represent or "stand for" something else. Our

culture is filled with them, including the Statue of Liberty, Valley

Forge, and the U.S.S. Arizona. [5] Arguably, Gettysburg is the

Civil War's most widely recognized symbolic place; and while Ft. Sumter

and Appomattox - where the war started and ended - are also very

symbolic, it is to Gettysburg that visitors flock by the millions.

Because such numbers do come to "see" and to "experience" Gettysburg, we

really should be conscious of its many symbolic aspects, for most who

are drawn here because of its aura leave the place believing that the

landscape they've seen and driven across is the actual

battlefield. [6]

But wait a minute, that is the

battlefield!

Well, no actually it isn't. What we see at Gettysburg

is a symbolic landscape that was created within a military park. On the

face of it, all of that should be obvious, except that this reality

often escapes us because battlefield, park, and symbol have become so

thoroughly blurred. [7] This transformation has actually taken a

great deal of time, but it started soon after the firing stopped. Even

as the debris of war was being gathered and as farmers were tearing down

breastworks and artillery lunettes to reclaim their farmland and fence

rails, the battlefield was being altered. [8] David McConaughy,

writing as early as July and August, 1863, decried those changes as he

and a few others struggled to begin their own transformative process to

memorialize and preserve the field. [9] It is significant for us

to know that everything we perceive as battlefield - all that we see

while driving along Hancock and Confederate Avenues and all that we take

in from Little Round Top's summit - is now a symbolic representation of

what we think it to have been in 1863. Everything.

Now perhaps it is not the worst of things that most

visitors drive by "The Copse of Trees" at the High Water Mark and

believe it to be "the" copse of trees, for most are truly effected by

the stories of the 3rd July struggle these trees help

signify. [10] The great dilemma arises when visitors and

students of the battle try to interpret, or "see" the copse as it was in

1863. The copse did not look as it does now. It was smaller. "But by how

much? Was the copse of sufficient size to actually function as an

artillery and infantry aiming point? How badly was the copse damaged?

How well did this tree cover serve to protect the defenders or impede

the attackers?" These are just some of the most basic questions that

arise when we attempt to really see 1863 but find our vision blurred by

the symbols. [11]

We can begin to appreciate that if we actually want

to understand the battle rather than simply move across its field from

symbol to symbol, we really need to know as much as we can about the

field's original appearance; but the unknown variables we especially

need to explore involve knowing how much throughout the intervening

decades the field has been altered, as well as when, why, and by whom. I

will close this essay with an example of that issue.

Thus far we have identified E. B. Cope as an heroic

figure and gained a philosophical understanding of the type of heroism

his figure exemplifies: a talented, common man doing essentially common

things but with remarkable skill, exacting quality, and duration. As a

symbol of Everyman, we see Cope's heroism linked to the creation of one

of America's most significant symbolic landscapes: the Gettysburg

National Military Park - which, itself, is a focal point commemorating

the heroic efforts of countless common people. We have also learned

that all that we know as battlefield has, in fact, been altered from its

1863 appearance, and that in order to truly understand the battle, we

need to understand the field's alterations.

As we begin to learn of Cope as a person, we'll first

explore, of all things, a musical metaphor.

The reference is to "Ein Heldenleben", Richard

Strauss' last great tone poem. "A Hero's Life" depicts the actions and

reactions of a great figure reflecting upon life's victories and

tribulations. Assuredly, E. B. Cope was not Strauss' model, for his life

was far from grandiose. But the point here is that Cope's life wasn't

the model for "Symphonia Domestica" either! In "A Domestic Symphony"

Strauss relates the ups and downs of a bourgeois man's family throughout

a typical day. Now, due to the nature of the few writings assembled

about Cope to date, he's usually been portrayed as a dour, pedantic

figure who "got the job done", and as a good family man who was a nice,

but a rather boring, chap. We'll find Cope to be far more interesting

than his stereotype (and as Everyman, how could he not be?)

To close this metaphor, Cope's life, like Strauss'

orchestration, was rich, full, fluid, and colorfully complex. Also,

please liken what is presented here to a biographical overture rather

than a detailed tone poem, for just as the overture of a musical or an

opera introduces themes and motifs that will be developed throughout a

larger work, so this writing serves to provide a range of information

and ideas that truly require a larger work to do Cope's life full

justice. He deserves a tone poem's worth of attention. [12]

Emmor Bradley Cope was born 23 July, 1834, the eldest

of ten children born to Edge Taylor and Mary Bradley Cope. [13]

Named for his mother's father, Emmor Bradley (1777 - 1837), he came

into the world at his family's homestead, a sizeable, 2-1/2 story,

five-bay stone farmhouse, banked into a slope near the picturesque,

historic Brandywine Creek. [14] His home formed part of

Copesville, a small collection of residential, agricultural, and milling

and manufacturing structures that straddled the township lines of East

and West Bradford in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Copesville may still

be found on the old Strasburg Road (Route 162) approximately two miles

west of West Chester. With a broad, stone-arched bridge built in 1807

near his front lane and the fresh flowing Brandywine by his yard's edge,

his childhood setting was both idyllic and industrial, and bucolic and

bustling; for Copesville was a busy milling and factory site throughout

most of the nineteenth century. [15]

The Copesville Copes were a branch of a prominent

Quaker family of strong lineage. Their English origins can be traced to

Wiltshire in the West Country and to the reign of Richard II (1377 -

1399). The family's American fountainhead was Oliver Cope, who came to

Pennsylvania in 1682 with William Penn. The Copes were very active as

merchants and financiers but were also successful in other areas. One

of E. B.'s distant cousins, Edward Brinker Cope, was "an eminent

scientist", while other English cousins were artists elected to the

Royal Academy. [16] E. B. and his siblings formed part of the

seventh generation of Copes who lived and generally prospered in the

greater Philadelphia region; and he and his younger brothers, Ezra and

Edge T., would become the third generation of their family's branch to

harness the Brandywine's waters to make their living.

Grandfather Ezra (1783 - 1840) was the first

of the family to take over what had been known as the "Buffington old

tilt mill property". He had an aptitude for more than milling. As a

mechanic and inventor, he secured a U. S. patent in 1825 for an improved

grain cutter called the Buckeye Mowing Machine which he also produced.

Ezra Cope was very active in county politics, having been both Treasurer

and Commissioner; and as a civic leader, in 1827 he was a charter member

of the Chester County Athenaeum. [17] Though he was mechanically

adept, there is some evidence that his skills did not extend to business

management, and finally, in 1837, he lost title to his

foundry. [18] Presumably the Brandywine Works, as the business

was then called, was recovered by the family, for E. B.'s father ruled

the operation for more than forty years.

Edge T. Cope (1810 - 1886) inherited his father's

drive and skills but also possessed far better business sense. The local

papers were liberally sprinkled with advertisements and notices for his

new agricultural items, like corn shellers, chums, clover mills and hoop

making machines. Cope expanded his production range (and certainly his

profits) by receiving contracts to produce "switches, chairs, bridge

bolts, car wheels, and axles" for the emerging Pennsylvania Railroad.

[19] He, too, was active politically and served for many

years as his township's Judge of Elections. [20] We have one

other insight into his life which, I believe, may have some bearing on

understanding E. B.'s own business and military careers: Edge T. was

not afraid to speak up, especially on behalf of his family.

The inkling for this opinion comes to light in an

incident where, "H. L. of Syracuse, N. Y." criticized the

capabilities of the family-designed mowing machines. [21] Edge

T.'s vehement response in the June, 1858 issue of the American

Agriculturist: follows:

. . . if he thinks he has a machine that will beat

either, in any respect all he has to do is to come to Chester Co. near

West Chester, and I will be ready to give him trial, in any kind of

grass - and let the farmers be the judges; we have some of the

tall grass in Chester Co. - and heavy too. I will mow with him in

lodged clover as well as in straight timothy [22]

Rhetoric of that sort was common then, but Cope's

challenge was clear, and it was issued in a respected periodical that

circulated nearly nationally. Perhaps there was an "edge" to Edge T.

More descriptions of his demeanor are found in a pair of obituaries:

"As a workman the deceased has few superiors, and

sent out from his shops a fine lot of work men. He was very careful of

his apprentices, and almost invariably took them into his own family."

The second states that the:

Deceased was recognized as one of the most active

and useful citizens in East Bradford, and indeed his business and career

won for him the confidence and respect of all with whom he came into

contact . . . His deportment was marked by uniform kindness and

urbanity . . . it may be properly said that one of the most highly

esteemed men of Chester County has passed from amongst us, whose place it

will be difficult to fill. [23]

It may also be properly said that the person most

likely expected to fill Edge T.'s place, and the person most probably

bred to fill that place was E. B. Cope. I believe we may presume that to

be true, especially given that he was an eldest son living in an era

when primogeniture was still an important social and economic dynamic.

And therefore, because so little of E. B.'s private life is actually

able to be documented, it has been doubly important for us to review

his forbearers' lives so that, at the least, we can understand something

of the role models he was most likely expected to

emulate. [24]

What is documented of his childhood suggests that E.

B. attended "locally run private schools" and that he possessed an

interest in and a talent for art. (One of his Gettysburg home's prized

objects was a picture of George Washington on horseback "which he

painted when he was twelve years old.") [25] All else must be

inferred from what we gauge his circumstances to have been: he was not

"boarded" away at school, nor did he attend any post-secondary

institution - nor perhaps even a high school; his home and the many

buildings that gave his family their livelihood and much of their status

were but a few yards apart. It is reasonable to presume that his

schooling (which may have been quite sound) was meshed with an official

or unofficial apprenticeship to his father's trades. Moreover, E. B. was

probably in and out of the mill and factories from his earliest years.

As we will find, E. B. certainly possessed the aptitude and abilities

to master milling, machining, and manufacturing, and his father (who

most likely held high standards) thought enough of him to later bring

him into the business. We can only speculate as to the nature of E. B.'s

relationship with his father, but we can be certain that familial and

economic circumstances mandated that it was a constantly interactive

one.

In attempting to form a sense of Cope's early life,

we may well be correct in picturing him as dutiful, intelligent, good

with his hands, and very mechanically adept. But we cannot overlook his

artistic side - for he maintained those interests throughout his very

long life, so we also need to picture E. B. as creative, sensitive,

expressive, adept at transforming 3-D images into 2-D renderings (i.e.

taking a real or a "made up" subject and painting or drawing it in a

recognizable manner; or in other words - being able to transform the

conceptual into something tangible - and that is exactly what he

would do at Gettysburg!), while also possessing an appreciation for

color, light, and composition.

Most certainly, E. B.'s interests and talents were

diverse, and that is worth remembering, for now that we've developed a

sense of Cope's heritage - essentially where he came from - and charted

the pathway he was most likely destined to follow, we will discover that

he chose to veer 180 degrees from that course. On 4 June, 1861, Emmor

Bradley Cope turned away from his heritage, left his family and his

father's business, and - as a seventh generation Quaker - went off to

war. One certainly wonders why? [26]

E. B. Cope most likely enlisted for one of or a

combination of the reasons any man enlisted: patriotic zeal, political

or moral convictions; a chance to leave home, see the world, prove

oneself; a relief from problems or boredom; or simply because it seemed

the thing to do, or that someone whose opinion mattered said it was the

thing to do.

He entered the service as part of Pennsylvania's

second great wave of volunteers. His unit, the Brandywine Guards, was

West Chester's local militia company. They formed as Company A, 30th

Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (First Pennsylvania Reserves)

on 9 June, 1861. Cope enlisted as a private, or more likely a corporal,

but was promoted (elected) to sergeant within his first week in

camp. [27] His regiment's encampment, Fort Wayne, was located at

the town's southern end. It was established through the efforts of

another Chester County resident - Major General George A.

McCall. [28]

Whatever Cope's reasons, he must have been highly

motivated to enlist for he was no teenaged farmboy without commitments.

His circumstances were as follows: he was twenty-five and older than

most of his unit; [29] most likely he was engaged, for he

married Miss Isabella L. Spackman a month later (11 July, 1861) in a

Quaker ceremony at the local meeting house; [30] he was a

skilled "machinist" and "manufacturer of machinery" who was integral to

his father's business; [31] and finally, it has been our

conventional understanding that he enlisted against his family's wishes

and that he was the only Cope to do so. [32]

The irony here is that even though running off to war

was a fairly conventional thing for a fellow to do in 1861, given Cope's

religious, familial, and economic circumstances, it was, for him, a

very unconventional thing! His decision certainly demonstrates the

strength of his sense of individuality, and it may also suggest where he

felt his duty must lie. His election as sergeant is evidence that he was

known, liked, and trusted by his neighbors, but that he did not hold the

political or social wherewithal to be an officer. Indeed, his

sergeancy does beg the question of his pre-war association with the

Guards, for it does seem unlikely that they would elect someone to such

a position from outside of their membership. It is an issue that merits

further investigation, as does Cope's pre-war relationship with General

McCall. It is highly possible, especially through his father's

connections, that E.B. and McCall knew each other. This relationship,

with others, proved to be an important strand in the network that helped

get Cope transferred to the topographical corps.

McCall, who was born in Philadelphia, had graduated

from the United States Military Academy in 1822. He served in the

regular army until 1855, having seen action in both the Seminole and

Mexican Wars. Two years after his retirement he moved to Belair, an

estate approximately one mile north of West Chester. Governor Andrew

Curtin appointed him a military advisor at the war's outbreak, and on

15 May, 1861, gave him command of the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps, which

would comprise fifteen regiments. [33]

General McCall held Cope's company in high esteem and

detailed them as his headquarters guard. When the Reserves were

transferred to Washington, D.C., the Brandywine Guards served him daily

while also learning to be soldiers. They must, at least, have looked the

part, for on 23 September during a review held for France's Prince de

Joinville, McCall took special pride in pointing them out to Major

General George B. "Little Mac" McClellan, [34] E.B. may not

have been present to receive that particular praise, for he had been

wounded a month earlier - not by a Sesech raider, but by one of his own

comrades. The incident's details are vague, but Alfred Rupert, one of

his company who was eventually promoted to first lieutenant, wrote of it

to his brother, "Sergeant Cope is better [.] getting along very

well [.] his father and mother came down in the next train after

you left. . .Cope intends going home for a few weeks until he

gets over [his] wound, the ball can't be found but the doctor says it

will do him no harm." [35]

It is possible that E.B. won the dubious distinction

of being the first in his company to be gun shot. We may presume he

carried that ball with him throughout the war and to his grave -

sixty-six years later. But Cope also carried other things with him into

the service: ambition and talent.

The writings of others in his regiment narrate the

fairly typical experiences common to all the units such as his who were

in training around Washington. Drills and reviews are mentioned but most

accounts suggest a fairly boring routine. Cope soon found an avenue to

more exciting duties, for on 20 September, 1861, he was "detached for

special duty at Division Head Quarters" by General McCall's

request. [36] His work there is unspecified, but it allowed him

to move in higher circles than most Quaker sergeants. He did have time

to indulge his artistic talents for he produced a woodcut likeness of

General McCall that was incorporated onto the general's headquarters

envelopes. The image surely pleased McCall, and the image also

demonstrates that Cope had a better than average grasp of the art of

woodcutting and perhaps even of engraving. [37] By spring, 1862,

E.B. had moved to another duty. Perhaps because of his penchant, or

interest, in mechanical devices, he was attached to Battery C, 5th

United States Artillery, per McCall's Order #74. He spent at least two

months there, and it was during this assignment that Cope's star began

to rise. [38]

Carrying on his family's gift for inventing things,

Cope sent a letter to the Honorable Edward McPherson (yes, of

Gettysburg's McPherson's Ridge) informing him of an interesting device

he'd just worked out which would, he thought, be highly useful in

determining artillery ranges from a fixed baseline using a form of

scaled triangulation. It seemed to give a higher degree of accuracy than

the standard drop-leaf tangent sight employed by artillerymen to register

their fire. [39] As per McPherson's actions, the plans for

the device were forwarded to Secretary of War, Edward

Stanton. [40] The device itself looked much like a footed

T-square with a sliding gauge which was then connected to a similar

piece by a one hundred yard chain. A good eye and a sense of basic

geometry were all that was required to employ Cope's invention. This

object's fate is unknown, but it certainly did not find its way into the

Union's field artillery chests. Most likely, its best use was for

ranging targets in siege or fixed fortification situations - or

perhaps in quickly establishing distances in certain map-making

exercises.

Cope participated in all of the Army of the Potomac's

campaigning throughout the spring and summer of 1862, although his

specific actions remain unclear. But as his talents became more widely

recognized at the proper levels, he was eventually granted his request

to become part of the army's engineering corps. His transfer became

effective 30 December, 1862 when he was "assigned to extra duty as

mechanic, and will be ordered to report to the Chief of Topographical

Engineers Army of the Potomac." [41] As an assistant to the

Corps' topographical parties, E.B. would receive an additional 40¢

per day. [42]

We may assume that E.B.'s training as a topographer

was on-the-job; but we may also assume that he was a fast learner for

he was already a strong draftsman and he was precise, intelligent, and

he thrived around mechanical instruments and on problem solving. He was

just the sort to be involved in topographical work.

Cope's first opportunity to display his abilities

came when he was assigned by General Warren to lead a work party to

survey the Antietam Battlefield. [43] This assignment would be

well completed, but as we will read shortly, it caused him some real

consternation.

By the 1863 campaign season's start, Cope had become

an integral member of the topographical engineers; but as his duties

expanded, one discrepancy arose: most men detailed to do major

topographical work were commissioned officers while E.B. remained a

First Sergeant. Cope wasn't shy about calling upon favors as is

evidenced in a letter from Attorney General Edward Bates to General

Warren in which Bates speaks of "my young friend, E.B. Cope" in glowing

terms and heartily requests that Warren push his promotion, for Cope had

written to him "stating his strong desire for promotion" and felt that

good words from Warren would clinch the deal. [44] Warren

responded the following day and described Cope to Bates as being "one

of my most efficient and useful assistants" and that "I have so much

desired his advancement as to speak of him with Governor Curtin, as

being most worthy of it." [45] But, as with working through any

bureaucracy, one's intentions may be good, but the wheels and cogs

usually grind slowly, and they certainly did in the case of Cope's

promotion. It was often the situation that special duty men were

required to pay for items and services directly and then submit their

bills for reimbursements. Cope's extra 40¢ per day didn't always

suffice, and so his lack of a commission became a real issue. But in

early June, 1863, as the Army of the Potomac started north to blunt

Robert E. Lee's plans for a second invasion of Maryland and

Pennsylvania, the issue of one topographical sergeant's finances was

deemed inconsequential.

Ironically, almost nothing is known about E.B. Cope's

actions during the Battle of Gettysburg, but as previously stated, his

heroic relationship with the field is a result of actions that

transpired long after the fighting ended. General Gouvenor K. Warren's

accounts mention many of his staff but contain nothing of Cope.

Presumably he was on the field, and presumably he was doing something,

but just what remains speculative. It is unlikely that he played a role

in Warren's now famous reconnoitering actions on Little Round Top (LRT)

during the afternoon of 2 July, and it would be futile to guess as to

his whereabouts. To date, there is but one citation mentioning Cope at

Gettysburg and it is an anticdotal account from one of the 155th

Pennsylvania Infantry stationed on LRT. While it does place Cope and

Warren together on the hill, it does so on 5 July.

"Before daylight on the 5th Meade and all his staff

were awake and alert for action. General Warren, accompanied by Captain

E.B. Cope, A.D.C., was dispatched to make observations of the enemy's

movements from Little Round Top as soon as daylight would allow a

view.

There, surrounded by the men of Weed's Brigade,

still fast asleep in their water-soaked blankets, Warren, with his

powerful field glasses, made important observations which caused him for

confirmation to ride to the advanced picket lines of Wright's division

of the Sixth Corps. This division then occupied the Peach Orchard, the

scene of the great fight of the Third Corps on July 2nd. Warren then

made a personal reconnaissance across the picket line and out along the

Emmitsburg Road and found all the positions of the enemy deserted, and

that Lee's entire army and trains had, under cover of darkness and of

the heavy rains, retreated during the night. Warren, on this discovery,

rejoined Captain Cope on Little Round Top and at once, representing

Meade, delivered to General Sedgwick orders to have the Sixth Corps,

then in reserve, immediately to march in pursuit of the retreating

Confederate Army. On Warren's reporting the retreat of Lee's army, General

Meade dispatched his cavalry in pursuit." [46]

It was during the weeks following the battle that

Cope's real association with Gettysburg began. General Warren assigned

him the responsibility of assembling the first comprehensive topographical

map of the field. This he did, mainly on horseback, within a

period of a week or so. Warren was so pleased with its quality he even

cited Cope's work on the margin of what we now call the Warren Survey,

and it is this document that has served as the base-line cartographic

source for all battlefield surveys from 1868 to the present. Warren

wrote:

"This is a photograph from a map mainly made by Major

(then Sergeant) E.B. Cope of my force (while the Chief Engineer of the

Army of the Potomac) and under my direction. It is valuable as showing

how a good topographer can represent a field after a personal

reconnaissance. It was mostly made from horseback sketches based upon

the map of Adams County, Pa." [47]

Essentially, Cope estimated and drew in hatchured

lines (a standard map making symbol) to denote the field's physical

features and elevations. His high standard of performance set

precedence for all subsequent mapping on the field. It was his first

great contribution to Gettysburg, and yet his actions were simply that

of an ordinary, yet talented man completing a relatively ordinary task

(at least for map-makers) but doing the task exceedingly well. Surely,

his actions were those of an heroic Everyman.

While at Gettysburg, E.B. was visited by his father

and related to him the dilemma which arose as a result of his Antietam

assignment. Cope had put the last touches on his Antietam map while

still working at Gettysburg. He then sent it off to Washington via one

of his assistants who, upon arriving at the War Department, promptly

took credit for drawing the map himself! As his reward, he was given a

discharge and hired on staff as a civilian topographical assistant - at

the rate of $4.00 per day. Cope was crestfallen, but did not press the

point, although his father certainly did in a letter that clamored for

his son to be promoted. He pointed out the unfairness of his son's

situation and also plead that he had a family to support and that "the

paltry pay" of a sergeant just wasn't sufficient. The most telling

information that Cope's father related is the long list of people who

had recommended E.B. for a commission. Impressively, it included Warren,

McCall, Attorney General Bates, his regiment's colonel and three

congressmen. [48]

E.B. Cope was finally promoted to captain and

Aide-de-Camp on Warren's staff on 20 April, 1864. [49]

Details of his subsequent service are also spotty, but we can assume

that he became a trusted member of Warren's entourage. Much of his

time was spent in leading surveying parties for the Atlas to the

Official Records lists him as the mapping authority for: Boydton

Plank Road, Va; Hatcher's Run, Va; North Anna River, Va; Spotsylvania

Court House, Va; and Wilderness, Va. He is also listed as the Senior

Engineer for: Bristoe Station, Va; Chancellorsville Campaign; and

Gettysburg, Pa. The many letterbooks found within the Warren Collection

at the New York State Library are liberally sprinkled with additional

Cope-made sketches and diagrams. They show a high degree of clarity

and a sense of style and detail that would become integral to the many

maps Cope would produce in his later years as the Gettysburg National

Military Park's first topographical engineer. (A fully cataloged

collection of Cope's maps would make a fascinating project.) As Cope's

relationship with Warren developed, he was further entrusted with the

responsibilities of any regular staff officer: there were messages to

relate, orders to force into action, and tempers and egos to soothe at

all times (and there was much of that to do in the Army of the Potomac

in late 1864-65!)

As the opposing armies locked onto each other and

combat became a daily routine, the dense Virginia landscape caused

tremendous problems for both staff and line officers. The few dozen

messages that exist between Cope and Warren certainly illustrate Cope's

ability to observe, infer, and communicate clearly; yet as in any

conflict, there existed certain situations that defied all reason and

befuddled those on both sides. Cope found himself in the middle of just

such a muddle in the dense woods near Hatcher's Run, southwest of

Petersburg, Va. General Warren related the story in his report to

Adjutant General Williams; the action took place in a light rain around

4:45 a.m.:

the enemy became so bewildered in these woods that

upwards of 200 of them strayed into General Crawford's line and were

captured. Some of these men before [captured] three of our ambulances a

mile in rear of General Crawford. Six of them captured Captain Cope of

my staff but finding themselves in our lines gave up to him and he

brought them in. [50]

Picture that! Even though now an officer, E.B. was

still plagued by financial troubles. In the following instance, General

Warren attempted to intercede on Cope's behalf. On 29 October, 1864 he

wrote,

Captain Cope tells me that the order he had for

making the surveys at Gettysburg was insufficient to enable him and

party to recover expenses incurred. It was written by Captain Paine

according to my orders as I had a great deal to do at the time. I now

send the order signed by myself on my endorsement to Captain Paine's

order for you to use in settling the account. If you do not feel

authorized to pay the amount on this, please return the paper to Captain

Cope with your reasons, and I will send them to Major Woodruff for

payment. [51]

One wonders if the reimbursement ever got

through.

With the resignation of Washington Roebling on 21

January, 1865, a major's commission opened on Warren's

staff. [52] (Roebling, by the way, was Warren's brother in law

and the man responsible for completing the Brooklyn Bridge.) Warren

was prompt to nominate E.B. Cope for the promotion. And four days later,

the War Department was equally prompt in announcing that they had no

paperwork for Cope's promotion. [53] While we can assume the

papers were eventually located - for Cope was promoted to major -

no one (including Cope) has any recollection of the effective date.

In his role as senior Aide-de-Camp, Cope was drawn

even more intimately into Warren's actions, and he was in the thick of

things at the Battle of Five Forks which proved to be General Warren's

downfall. Accused by General Philip Sheridan of being dilatory and of

not following orders, Warren was chosen to be the scapegoat for many of

the Army of the Potomac's bungles and crossed messages that abounded

during the war's last weeks. Warren was relieved of command, and he

would spend much of the rest of his life seeking vindication.

Major Cope had his own troubles at Five Forks. He and

his orderly had spent many hours reconnoitering and checking troop

movements, and they were dead tired. After a short night's sleep they

set off to find Warren's command. In riding toward the Gravelly Run

Church, Cope missed a turn and headed directly to Five Forks, getting

within six hundred yards of the site. In his advance, he passed through

his own line of cavalry videttes. They did not bother to tell him they

were the last outpost, so Cope rode directly into the Confederate

pickets who promptly shot his horse from under him. He and his orderly

made a hasty escape. [54] Major Cope, now horseless, took the

liberty to "borrow" another animal from one of his headquarters friends

who was on temporary duty elsewhere. The friend was Charles Reed,

formally of the 9th Massachusetts Battery, which did such remarkable

service near the Trostle house during Gettysburg's second afternoon of

mayhem. In a letter to his mother, Reed complained that Cope had "used

up" his horse "with hard riding"; but as the war finally came to a close

and the victorious Army of the Potomac moved back toward Washington, he

and Cope "took turns" riding the beast so as not to jade him

further. [55]

By the war's end Emmor Bradley Cope had risen from a

corporal of infantry to a major and senior-Aide-de-Camp in the

headquarters of one of the Union Army's more active and more controversial

generals. He served in the ranks, he worked with artillery,

and he displayed his artistic and inventive flairs in many ways. He

became a master topographer, a trusted staff member and, most likely, a

confidant to Warren. Throughout it all, his work was excellent, his

character noteworthy, and his sense of detail unflagging. For all this

and more, General Warren recommended Cope for a brevet, or honorary

promotion, to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, "for gallant conduct in

Battle of Five Forks in which he had a horse killed under

him." [56] This brevet was eventually awarded, and I believe it

pleased E.B. Cope tremendously. He had gone off to war to answer his

own inner calling, he returned whole, and carried with him the knowledge

that he had done well and that others recognized the fact and appreciated

his efforts. Ever the stickler for detail, Cope travelled from

Washington to the Headquarters of the Department of the Mississippi in

Vicksburg where Warren had been "reassigned" following his Five Forks

troubles - simply to get the proper signature for his

discharge! [57]

During E.B.'s absence, the waters of the Brandywine

kept flowing and kept driving the wheels of the family business. We can

imagine that Edge T. Cope was quite happy to have his eldest son back at

work, for he was now in his mid-fifties and probably needed the help. By

1868, the business letterhead was changed to read "ET Cope and Son,

Founders and Machinists." [58] Cope must have been very occupied

between helping with the family business and helping with the business

of having a family himself. His eldest child, Helen L. had been born

while E.B. was away at war, but between 1866 and 1873, E.B. and Isabella

gave Helen another five siblings. [59] His family lived in a

very modest two story frame house sited a few hundred feet west of and

upslope of his father's house. [60] Throughout the post-war

years the local papers were filled with items pertaining to the Copes'

mills and foundry, and to the many new products they had to offer like

churns, improved mowing machines and sophisticated water wheels and

turbines. [61] So, on the face of it, Cope's business was

flourishing and he was fully occupied. Again, details of his life are

not readily available, and it is therefore necessary to "read between

the lines" as to his activities. For instance, even though E.B. was an

inveterate reader, he had no affiliation with the nearby Copeland

Literary Association, though his brother, Edge T. Cope, certainly did.

Perhaps E.B. had little time or interest to attend such affairs where,

during their 10 February, 1872 meeting, the Association firmly resolved

that "modern dance is injurious to society." [62]

One thing that Cope did do was to stay in touch with

Gouvenor K. Warren, his old commander. On 21 December, 1866 he

responded to a letter Warren had written to him, presumably to ask Cope

how he was doing, and he thanked Warren for helping him receive his

brevet lieutenant colonelcy. [63] A few years later, as Cope

was again following family tradition by entering local politics, he

wrote to Warren for a letter of endorsement. He stated:

I am about to make an application for the office

of Collector of Internal Rev, 7th District of Pennsylvania. It is an

office that has never been held by a soldier. I must respectfully ask a

few lines from you no matter how brief regarding my military record, for

which I shall be extremely obliged. [64]

Cope would eventually take office as a township

auditor and held that position sporadically between 1886 and 1893. [65]

E.B. Cope also continued to invent things, and on 29

June, 1875, he received a patent for a very elaborate form of water

turbine. [66] A multi-paged, many-diagramed prospectus for this

piece was developed, and this turbine was a featured item in the great

Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia in 1876. An autographed copy

of the prospectus found its way into G.K. Warren's papers. [67]

It is worth mentioning that even though E.B. Cope was

accessible as a resource (and most probably was quite willing to serve

as such) he had no involvement in the 1868-1869 efforts to resurvey the

Gettysburg Battlefield for its inclusion in the Atlas of the Official

Records. Nor, for that matter, was Warren intimately involved even

though we refer to that document as the Warren Map or the Warren Survey.

The work was obviously based on Cope's horseback survey, but

absolutely no evidence has thus far come to light suggesting that Cope was

even contacted. Instead, much of the fieldwork was directed by First

Lieutenant William H. Chase of the U.S. Engineer Battalion. He and his

teams would spend months on the work and would produce, arguably, the

battlefield's most important cartographic reference. [68]

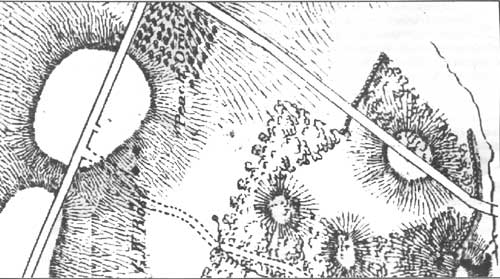

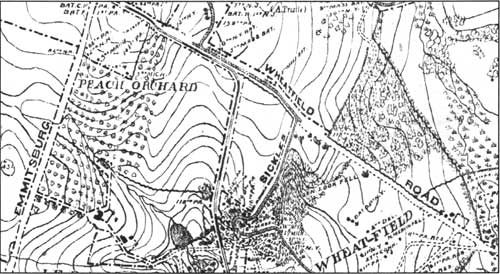

A portion of Cope's 1863 map showing Peach Orchard and Wheat Field.

|

(GNMP; click on image for a PDF version)

|

A portion of Cope's 1905 "Commission Map" showing the same area.

|

(GNMP; click on image for a PDF version)

|

Cope made his first map of the battlefield

(portion at top) within two months of battle. He made his most complete

map (the bottom view of the same area) in 1905. On his first mapping

trip in August of 1863 he had crude resources and made the map from

horseback. By 1905, however, he had become more aware of each portion

of the field and had a great impact on how it looked.

But E.B. Cope also turned out some key cartographic

references of his own during these years - and mainly for Gouvenor K.

Warren. This situation seemed to arise after Cope (who apparently lost

contact with Warren for an unspecified time) wrote to him to ask Warren

to help him obtain copies of the Gettysburg maps he worked on in 1863.

Cope wrote,

I once wrote to the Bureau at Washington begging

a copy of the map of [Battle of Gettysburg] I had assisted in making. No

notice whatsoever was taken of the request[.] General Crawford called at

my place several years ago, thinking I had maps, or copies of maps of

all battlefields. He was about to write a history of the war I had

none. [69]

Warren quickly responded and did procure maps for

Cope which he received within a month. [70] Soon thereafter,

Warren began to correspond with Cope regarding certain military incidents

and began to retain his services as a cartographer. He was first

invited to meet Warren at Manassas Junction and work on portions of the

field for between two and five days. Warren stated, "I have means to pay

your expenses and a per diem of $5.00. I should like personally

to meet you very much; and if you can come there about that time, I will

introduce you to those investigating that battle. I know you can help

them in the matter; and that you will but add to the numbers of those

who appreciate you." [71]

As you might be beginning to suspect, Cope's work

eventually expanded to produce a series of maps and sketches that Warren

brought into evidence during the long Court of Inquiry concerning his

conduct at Five Forks. Cope himself would also testify in Warren's

defense. [72] The quality of Cope's drawing probably aided

Warren's arguments and they are comparable to the work he produced

during the war years, and with his later work at Gettysburg.

When E.B. wasn't off surveying, he was working to

hold the family business together. His father finally retired in 1880

and turned over the enterprise to Emmor and his younger brother

Ezra. [73] Six years later, E.B., his family, and many friends

and neighbors stood in a near freezing, windblown rain to lay Edge T.

Cope to rest. [74] Emmor Bradley Cope had become the family

patriarch. Although he tried diligently to keep his family's very diverse

operation solvent, toward the end of the 1880's there are growing

indications that business was not going as well as it should. Cope

himself would write letters to customers kindly asking for payment for

services or for work already delivered, and there is often an urgency in

his words. Even though the firm attempted to continue expanding and

even diversified to the manufacturing of manilla paper, their financial

situation worsened. [75]

Finally, in the spring of 1890 two suits were brought

against the Cope business which resulted in Sheriff's sale

proceedings. [76] The exact disposition of the business is

sketchy, and the firm of E.T. Cope's Sons continued operating but, most

likely, in a greatly reduced condition. It is no wonder that by the

early 1890's, E.B. Cope was receptive to exploring other means of making

a living. In 1893, such a chance came to him.

About the same time Cope was struggling with the

family business, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA)

was struggling with issues of organization, finance, and vision in

relationship to the preservation of the field they were responsible to

maintain. The GBMA had been troubled almost since its chartering in

1864. Its primary impediments were its control by locally-oriented

entities and its lack of finances. Even in the 1870's when many Grand

Army of the Republic (GAR) members and other veteran's organizations

began taking a strong interest in the GBMA's activities (or lack

thereof), a unified vision and the fiscal resources to create and

maintain that vision remained serious, unresolved problems. With the

battle's 25th anniversary celebration in 1888, veterans from across the

country became painfully aware of the GBMA's lack of structure at a time

when more than two hundred regimental and state-funded monuments had

been placed on the field. However, it would be the proposal by a handful

of private developers for an electric railway that would bisect the

field and threaten its visual and topographical integrity that finally

spurred the U.S. Congress to place the battlefield under federal

control. [77]

On 25 May, 1893, Secretary of War Daniel S. Lamont

appointed a three-person commission to oversee the activities that would

lay the groundwork for the present GNMP. Their tasks included

preservation, marking battle lines (of both northern and southern

armies), building avenues, and interpreting the battle. The first

commissioners were Colonel John P. Nicholson of Philadelphia, General

W.H. Forney of Alabama, and John B. Bachelder, the field's

unofficial/official historian. This group soon realized they needed a

full-time, on-site engineer to fulfill their plans, and a position was

soon authorized. [78]

It is not known how E.B. Cope was identified as a

candidate for this position, but by 1893, he probably needed a steadier

income than what his business was providing and welcomed the

opportunity. I would speculate that given Cope's war time political

connections, one or more of them mentioned Cope as a candidate - and he

certainly was a strong candidate. It might prove useful to explore any

connection Cope may have had with Nicholson in nearby Philadelphia, but

that line of research is only born in speculation. It should be noted

that Cope was not the only nominated candidate, and we have a clear

account of how this position was filled from the minutes of one of the

Commission's meetings:

Various communications were read from the

Secretary of War relating to the Trolley Road on the Field, and from

Colonel Cope and Mr Dager, applicants for the position of Chief Engineer

to the Commission. Colonel Cope appeared before the Board and explained

the details of the work suggested and withdrew Mr Dager appeared and

explained the details as suggested to him with his qualifications and

withdrew. The Board adjourned at 12:15 p.m. [79]

Their 3 July entry states:

Communications were read from Mr. Dager and Colonel

Cope respectively offering their services at $2000 per annum each.

Colonel Bachelder moved that the matter be referred to Colonel Nicholson

with power to act. [80]

And so he did. Emmor Bradley Cope reported for duty

on 17 July, 1893. Just as DeFoe's Robinson Crusoe, Cope entered his new

situation by taking stock of all he had with him. In his case, it was a

thorough list of all the engineering instruments he'd brought from his

home, and of the additional instruments he had been authorized to

purchase. [81] Cope then began to get acclimated and to assemble

what he often referred to as "the Corps," which consisted of three to

sometimes seven assistants. Throughout late July and early August, Cope

was employed with basic surveying work like establishing a meridian

line, and with "shooting in" some of the field's more prominent

features and its adjoining farm tracts. His work on 26 July is worth

citing entirely:

I caused an iron pin to be driven at the centre of

the square of the town of Gettysburg to be used in our work as a datum

point of reference, for the town is the centre of gravity of the

Battlefield. This point was afterwards connected with a meridian line that I

established on high ground of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial

Association, your Hancock Avenue. The north point of this line is near

the 126 New York Infantry monument and is marked by a brass point in a

granite stone set 30" in the ground, the south point is similarly marked

near the line of the George Benner property, using this meridian line as

a base of operations, many miles of back site transit lines have been

run on various parts of the field. [82]

Essentially, what Cope described therein is the

skeleton - the surveyor's very backbone - from which all other elements

of the field would be measured and related to. In following Cope's many

detailed entries, we can literally chart, segment by segment, the

creation of the Gettysburg National Military Park!

And this introduces quite a dilemma. If we were to

examine and relate all of Cope's work and his countless

contributions, this writing would stretch to hundreds of pages. Instead,

it is my intent to provide an overview of Cope's major activities, and

then briefly address three areas which, in my opinion, comprise his most

significant contributions to the military park and to the creation of

the symbolic landscape we visit so enthusiastically. As previously

stated, it was Cope who saw to the park's basic outlines and it would be

he who fairly well administered everything else the Commissioners

undertook, for E.B. was the only one of them who became a full time

Gettysburg resident and he would be the one who was on the field nearly

every day for over three decades. Cope moved his family to town in early

October, 1893 and lived first on Chambersburg Street. [83] The

family would later move to 516 Baltimore Street and that residence would

serve as Cope's Gettysburg homestead. [84]

With the establishment of Gettysburg as a National

Military Park in 1895, the work of the Commissioners and of their

engineer began in earnest. By that time, two of the original

commissioners, Forney and Bachelder died and had been replaced by

William Robbins of Alabama and Charles Richardson of New York. In

partnership with Nicholson and Cope, these four were responsible for

effecting an amazing transformation of the battleground. In a mere ten

years they:

transformed the muddy "cowpaths" of the GBMA into

over twenty miles of semipermanent "telfordized" avenues which to this

day provide the base for the macadamized avenues. Defense works were

resodded, relaid, and rebuilt where necessary. Cast iron and bronze

narrative tablets were written and contracted for to mark the

positions of each battery brigade, division, and corps for the armies as

well as the U.S. Regulars. More than 300 condemned cannon were mounted

on cast-iron carriages to mark or approximate battery sites where

convenient. Five steel observation towers were built at key overlook

points to assist in instructing military students in the strategy and

tactics of the battle. More than 25 miles of boundary and battlefield

fencing was constructed, as well as 13 miles of gutter paving. In excess

of five miles of stone walls were restored or rebuilt, and nearly 17,000

trees were planted in denoted parts of the field, including Ziegler's

Grove, Pitzer's Woods, Trostle Woods, and Biesecker Woods. More than 800

acres of land were acquired, including Houck's Ridge, the Peach Orchard,

and several significant battlefield farms and their structures

(McPherson, Culp, Weikert, Trostle, Codori, Frey, etc.) [85]

When reviewing this incredible list, please remember

that E.B. Cope oversaw most of it, in addition to keeping the books,

paying the workers, producing plenty of maps, and simply "taking care

of business." Also, when studying this list of accomplishments (which

does not include all the park's subsequent work from 1905 to the

present), can you now more fully accept why I maintain that what we see

at Gettysburg is symbolic landscape rather than battlefield?

Now, in light of all this work, plus more, I would

like to touch upon what I believe are Cope's three most significant

contributions. They are; 1. his record keeping and tireless attention to

detail, 2. his design and placement of the park's road system, and 3.

the erection of the park's five observation towers.

Moreover, throughout Cope's involvements in each of

these areas, he consistently displayed the traits of an heroic Everyman:

he possessed vision, demonstrated precision, and he did so with

unflagging energy.

No pun intended, honestly, but E.B. was a copious

writer. He left three hefty engineering journals which daily chart his

first years on the field. Much of his later writing formed the core of

the Commission's annual reports. Cope maintained constant contact with

the three commissioners, often writing them two to five letters a day.

He would apprise them of work done, relate problems, seek advice or ask

for clarifications, or he would remind them of impending issues. Much of

this correspondence is extant. The Park's vertical files are also

filled with Cope correspondence, usually arranged topically, like

documents relating to walls and fences, contracts, guttering, artillery

tubes and carriages, etc. I would estimate that the Park's vertical

files and its other repositories hold more than a thousand

Cope-generated or Cope-related documents.

|

|

(GNMP)

|

This amount of material should not really be

surprising, for Cope actually designed much of the Park's infrastructure

including its curbing and guttering, fencing and gateways, the brigade,

division, corps, and battery markers, the markers to the U.S. Regular

units, and the beautiful U.S. Regulars Monument located on Hancock

Avenue. He was also responsible for designing more mundane objects like

the cast metal gun carriage replicas and even the stone supports upon

which their wheels and trail pieces rest. We do need to remember that no

models for most of these things existed, for nowhere else in the world

was there a military park like Gettysburg. Cope and the Commission were

designing and building a prototype landscape consisting of unique

features and fittings.

E.B. also generated dozens of high quality

blueprints, sketches, section drawings, and a full series of battlefield

maps scaled at four foot contour intervals. The detail on these

documents is invaluable. Another of his legacies is the massive wooden

relief map (9'3" x 12'8") of the battlefield currently exhibited in the

Cyclorama Center's upper lobby. Based on the Warren Survey, this 3-D

depiction of the field was exhibited nationally, including being shown

at the great St. Louis Exhibition. This model is yet another reminder of

Cope's artistic, inventive nature. [86]

The details found in Cope's writings, especially in

his journals can be exciting as well as pedestrian - for he

noted nearly everything. In scanning them, one finds that Cope spent

a lot of time on the field. Not only was he constantly

supervising the work crews, he was constantly noting little things that

"needed to be done." For example, each month he made up a "to do" list,

and his July, 1914 sheet contained 69 items. These items could range

from gutter clearing to fence mending, to road patching, and to fallen

branches that needed gathered. E.B. Cope was the eyes and ears of the

Commissioners; he was the Park's ultimate builder, and he was its

quintessential protector.

I will cite just a sampling of his attention to

details. His journal entry for June 12, 1897 includes the

following:

John Took was put to work at sawing off posts at

Hancock Statue. went out with the Commission to first days field. at

about 11 AM a blast threw a stone against the 44 N.Y. Mon breaking a

spall off of the bead running around the monument. the piece is an

average of half in thick [87]

Cope included a small diagram of the damage. His

next entry stated: "Went out with Major Richardson to view the 44

Monument damage and ordered no more blasting there until the monument

was perfectly protected." [88]

The blasting in question was likely related to the

construction of a portion of old Sykes Avenue and took place somewhere

to the east or southeast of the monument. Cope saw to the replacement

of the damaged portion and those with a keen eye can find the

replacement segment of the astragal (the beaded stone course set about

eight feet above the monument base) on the monument's east side to the

north of the doorway on the rounded portion that contains the

stairway.

Cope always had the best interests of the Park and

the Commission in mind, and in this instance, he was remarkably

proactive to a potential problem:

Fred Thom's daughter age 15 at Seminary last night

coasting with a party of companions fell into Dr. Richard's cesspool and

was drowned not missed at first discovered at midnight covering had

rotted no repairs or danger sign.

He then writes:

I sent J. Aumen to examine all the well covers on

the field, of which there are several, and report if any need renewing

it shall be attended to at once. So far we had no accidents on account

of the carelessness of anybody connected with this Commission.

[89]

Sometimes Cope's entries involve more humorous

details.

Chief of Police Gordon made a present of over half

bushel of shell bark hickory nuts to the Commission for the squirrels. I

will send them out by Lott to Reynolds, MacMillan, Spangler's, Hafer's

and Round Top Woods and [have] them put in proper places. Other Hickory

nuts have been given to Spangler for Culp's Hill. [90]

Cope's writings are essential to the understanding

of the battlefield and to its transformation to symbolic parkland. The

Park's whole story from that era is nearly intact, but it is not easily

accessible nor is it easy to interpret; yet as I will maintain in this

writing's final portion, it is imperative that historians understand the

field's transformation, for if they do not, we run the risk of placing

vast numbers of combatants upon terrain features that did not exist in

1863.

Here is just one example of a Cope entry that clearly

notes change over time, and it should pique anyone's interest who might

be studying Little Round Top's terrain:

11 cords of wood no logs cut between the Round

Tops '2 roads, Tiptons line [on present Warren Ave.] and union stone

wall around D. Wikert is 2 cords near 9 reserve 3 cords, all that is cut

and corded up to this date [1896] total 19 cords. [91]

What might this tell us about the nature of the

area's tree cover and how much it changed between 1863 and 1896? And

what are the ways we might interpret this information to explore the

line-of-sight issues between Vincent's Brigade and Oates' attackers on 2

July?

The ultimate value of E.B. Cope's writings and

attention to detail is that we can literally recreate the construction

of the military park week by week and month by month. It is a fabulous

legacy when cross-referenced with other primary sources, and it is

material that has been very much under-utilized in our study of the

battle.

Before Cope's efforts began, as early photographs

clearly attest, the "avenues" of the GBMA were nothing more than rutted

dirt paths. E.B. was equally assiduous when it came to dealing with

roadways, and one of his first major tasks was to create the "boiler

plate" for the Park's paving contracts. He based his specifications on

a paving method known as Telfordizing (named for the mid-nineteenth

century British civil engineer who invented the process), and that meant

the Park's roads were being designed to last. Cope's paving was to be

completed as follows:

The center portion of the roadway feet in width

should be piked with a fine course of stone 4 to 5 in size laid on edge,

settled down evenly and compactly with raping hammers [.] this

course shall be then covered with a layer of good hard 1 in. stone 4 in.

in depth. This last course shall be covered with sufficient clay to form

a bond and then thoroughly rolled until the surface is hard smooth and

compact so that the wheels of a carriage passing over it will not leave

an impression. The whole surface of the piking to be covered with a

light coat of stone chips or screenings sufficient to conceal the clay

and rolled down hard and smooth. [92]

As with all else, E.B. paid great attention to the

road construction as this anecdote attests:

. . . two contractors, Mike and Tim Farrell of

West Chester, Pa., were awarded the contract for building many of those

Teleford and Macadam avenues. One day my father [Jesse K Cope] met Tim

Farrel on the street in West Chester, who said "Mr Cope that brother of

yours, the Colonel, is a hard man." We were starting on the

construction of an avenue according to the specifications and on that

day the Colonel was called away on official business and since he always

kept his eyes on any work done in the Park, we thought that we would

make time in his absence. The next morning, when I went into his office

to report and told him that we had laid one fourth mile of an avenue, he

said so I have observed and it is not according to the specifications, I

have been out there before you were up this morning, I dug up a section

of it, now you get your men out there dig up all of that section and

rebuild it according to the specifications which I gave you! He is a

hard man! [93]

Space does not permit a full examination of the

relationship between Cope and the Farrell Brothers, Michael and Timothy,

and I wish to be careful not to cast aspersions, but the Farrells were

from West Chester and lived less than a mile from Cope's residence. In

their earlier years, they were helped in establishing their business

(quarrying and stone building) by none other than General George A.

McCall, and they would win the bid to fulfill every road contract

on the Gettysburg Battlefield. Every one. And some bids were remarkable

close. [94] (There are many other relationships that interweave

throughout Cope's career, especially between other members of the

topographical engineers, but this line of research does not fall within this

writing's scope.)

What is more significant than the quality of the

Park's roads and the process by which they were built (although a

tremendous amount of data about the field is also contained in these

records) is the whole issue of where the roads were placed and how they

effect our interpretation of the battle. Certain of the roads existed at

the time of the battle or were widened from pre-existing lanes and

paths. Others were cut specifically to parallel battlelines or to allow

visitors easy access to more remote parts of the field. In some

instances, road alignments conformed to where early monuments had been

placed, but in other instances, especially with West Confederate

Avenue's many segments, the roadbed fairly well determined where the

Confederate monuments were to be erected. Now, as any engineer will

attest, you can not put a road just anywhere, and in this era of road

building, one needed to consider the degree of slope and turning radius

that horse drawn carriages could negotiate. The implication here is

that sometimes roads could not be built exactly where the

fighting occurred. (The same, incidentally, can be said for monument

placement.)

Roads also needed to be well drained, so this

entailed banking, cutting, filling, guttering and channelling, and many

other intrusive operations that we as non-engineering visitors rarely

consider. All of this requires substantial earth moving. In reality,

it would be quite accurate to state that the construction of the Park's

roads caused more significant change to the battlefield than any other

factor. Whole hillsides were affected, low lying areas filled in,

boulders blasted (not only to clear the way for roads, but also to

supply road bed ballast and other related material), and field

elevations raised or lowered that alter or confuse our sense of the 1863

terrain and lines-of-sight.

Cope's roads are excellent roads, and many remain

virtually unchanged (except for more modern paving) since their

construction; but they have dramatically altered the field itself - in

both subtle and blatant ways - and, even more significantly, they have

determined how most everyone views the battlefield. Practically every

soldier walked across these fields and from all angles and many

directions, but because of the roads almost every visitor since the

1890's has ridden or driven across the battleground in very prescribed

manners, and now visitors do so in air-conditioned comfort, or with

headsets affixed, or with eyes scanning everywhere - looking out for

other cars, pedestrians, animals, and the many signs or the next

way-side markers to read. Thus the roads can actually isolate visitors

from the field by channelling their senses; and with the roads many

twists and turns (think of Sedgwick and Brooke Avenues as examples) they

can sometimes confuse rather than clarify where visitors believe they

are. Certainly, the roads are necessary to accommodate the lay person's

ability to interpret the field, but they are also significant intrusions

that often skew one's ability to understand the 1863 landscape. As an

example of how much we rely upon the roads, try to imagine where the

Union line actually ran if the monuments and the roads were removed.

It is likely that there is no person living today

who can remember visiting the Gettysburg Battlefield and not seeing the

Commission's observation towers. They have been integral to the

battlefield's landscape for a century and it is very difficult to filter

them out of one's view. They offer both pleasurable experiences and

some problems. The vistas from their platforms are most wonderful, but

these vistas encompass far more than just the battlefield, and unless

one knows exactly where to look and what to look for, or is in the

company of one who knows "what's out there," the towers provide little

more than a great series of panoramic photo opportunities along with a

burst of healthy cardiovascular exercise getting to the top.

These towers quite unnaturally provide a perspective

that many generals on both sides would have loved to have had in July,

1863, and that is the point: no soldier ever had such a perspective, and

the clarity the towers may afford to us also skew our own sense (which

we really need to have to understand the battle) of how unclear and

confused the field was to most soldiers who fought there. From general to

private, most at Gettysburg had little or no idea where they were, where

they were going next, or even how to get there.

Essentially, these towers bring an unnatural order to

a field where disorder was quite natural. Another point to ponder is

that when these towers were erected in 1895-1896, they were as visually

intrusive to the battlefield's landscape as Ottenstein's National

Tower is at present. Also, because the towers are so prominent, they can

help establish handy reference points (like viewing the Culp's Hill

tower's cupola from LRT to form a sense of the "fishhook-shaped" Union

line), but many visitors also naturally assume that their prominent

placement is somehow significant. For the Culp's Hill (Tower #4), Oak

Ridge (Tower #3) and to some degree the Ziegler's Grove (Tower #5)

towers, their siting is relevant to segments of important actions; but

the Big Round Top (Tower #1) and Warfield Ridge (Tower #2) towers, were

simply placed to provide comprehensive views - the plan being that the

towers were to ring the battlefield, and therefore provide vistas of

every part of the Park.

Now, when these devices were erected, they were done

so to enable "students" of the field, both military and civilian, to get

a good bird's eye view; and, I might add, a free view. In prior years,

shorter towers existed on East Cemetery Hill (where the Hancock monument

now stands) and on the summit of Big Round Top; but one needed a change

purse for those.

E.B. Cope designed these towers - every part from

base to flagpole. They came in two sizes, a 60 ft version, and a 75 ft

version. Go look at one closely sometime. They are graceful yet utilitarian,

and sturdy yet not overbuilt. Their blueprints show Cope's

meticulous sense of detail, and illustrate that he obviously put much

thought into their utility and cost effectiveness. [95] When