|

THE BATTLE OF WILSON'S CREEK

For Missouri, the years immediately preceding the Civil War personified

its status as a border state. As the national debate over the institution

of slavery drew the new West into its scope in the wake of the war with

Mexico, Missourians saw the debate over their own statehood rekindled

and thrust into the national forum. The very boundary that was their

state's southern border—the 36°30" parallel—became

alternately the seed of harmony and discord between slavery's

restrictionists and extensionists. As Congress debated afar the future

of the vast territories taken from Mexico and as the nation's

politicians contorted over it in the subsequent electioneering mayhem,

the sacred parallel became a regular topic as a practical compromise

line upon which to organize the entire region.

Just as the debate lay the state's name yet again on the lips of the

nation's leaders, so did it isolate Missouri as potentially the only

slave state situated above the parallel. The Compromise of 1850

essentially sidestepped the issue by avoiding the Louisiana Purchase

entirely, allowing all the remaining portion of the Mexican Cession

save California to organize on the murky principle of popular

sovereignty, whereby the residents of the territories—rather than

Congress—would decide whether slavery would exist there upon

statehood. Missouri was thus segregated even further, the only state

allowed to have slavery in a northwestern region that, by permanent

decree, forbade the institution. More confusing, Missouri was now

situated alongside the remaining northern expanse of the Louisiana

territory, whose future was barred from slaveholding

by the very act that had breathed life into Missouri. As Missourians

did all in their power to maintain their allegiance to the democratic

Middle West, the nation's newest paroxysm over slavery forced them

glaringly into the role of outsiders.

|

ON MAY 21, 1856, PROSLAVERY BORDER RUFFIANS DESTROYED THE FREE STATE

HOTEL, DEFENSE HEADQUARTERS FOR THE ABOLITIONIST TOWN OF LAWRENCE,

KANSAS. (LC)

|

|

PROSLAVERY FOLLOWERS OF CHARLES HAMILTON MURDERED FIVE KANSAS CITIZENS

ON MAY 19, 1858, NEAR TRADING POST. THE MARAIS DES CYGNES MASSACRE AND

OTHER VIOLENT ACTS IN THE KANSAS TERRITORY SHOCKED BOTH NORTHERNERS AND

SOUTHERNERS. (KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

Similarly, Missouri's white population set the state at odds with

others of the Middle West. In 1860, nearly 75 percent of its 1.2 million

people were of southern heritage, and many of the remainder (especially

outside St. Louis) had come from regions in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio

that had been settled originally by emigrants from the southern states.

Of the 431,397 Missourians born outside the state, 273,500 came from

slaveholding states, especially from the upper South states such as

Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina. While its economy was

increasingly linked by rail with the industrial cities of the North

(rather than the traditional river connections with New Orleans), its

white populace had deep cultural ties with the slaveholding states.

Missourians—as

westerners—considered chattel bondage the marrow of freedom itself

and Missouri, as one observer hailed, was "the strongest pillar in the

temple of Democracy on the Western Continent."

|

More than culture tied Missouri with the states of the South. Between

1830 and 1850, Missouri's slave population more than tripled to 87,422;

by 1860, that number had increased by another third to 114,931, an

all-time high. More than thirty-five thousand of these slaves labored in

the central Missouri River counties, with the rest spread largely along

the Mississippi and in western Missouri. Rather than signaling any death

knell in the state, raw slave numbers in Missouri actually increased

during the same period, and they did so far more dramatically than their

proportion in the state's overall population declined. Inflated prices

of slaves (prime field hands fetched routinely as much as $1,500)

offered no indication that chattel bondage was waning in Missouri. Nor

should they have; in the last antebellum decade, slavery in the state

was thriving.

Unlike the states of the Deep South, where plantation agriculture

made slavery indispensable, Missourians held tightly to the "peculiar

institution" for more abstract reasoning. In their quest for personal

freedom, these uplanders legitimized slavery as embodying not just

western but American progress. Early national Americans whether northern

or southern, looked to the West as the region that would legitimate the

triumphant republic, that would assure its march toward world power.

Many moved there precisely because of its promise, as well as to escape

the restrictions of the more-settled East, to find liberty. Slavery,

viewed as one of those liberties, was thus no privilege in the West.

Farmers on the western border saw the peculiar institution not so much

as a constitutional right, the dais from which some of its leaders would

later deliver their dissevering sermons, but as a natural,

democratic right. While planting, weeding, and harvesting crops,

felling trees, processing hemp or tobacco, hauling water, and other

forms of labor that needed to be performed on farms and in manufacturing

establishments might have been the traditional services for which middle

Missourians sought slaves, labor needs did not prove the sole reasons

for their ardent support of the institution. Slaves were a means to an

end, rather than an end in themselves, and that end was true democratic

ascendance as much as any antislavery ideologue in the North claimed the

opposite. Far from being insouciant about the institution of slavery,

Missourians—as westerners—considered chattel bondage the

marrow of freedom itself and Missouri, as one observer hailed, was "the

strongest pillar in the temple of Democracy on the Western

Continent."

|

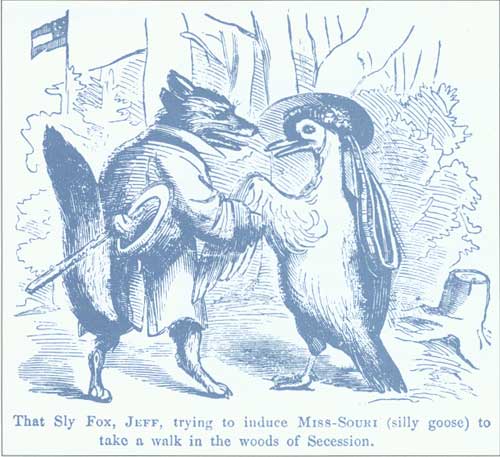

A POLITICAL CARTOON FROM JUNE 1861. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

With the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 as the nation's

sixteenth (and first Republican) president, the country moved rapidly

toward war. In rapid succession, seven southern slave states seceded

from the union of states, creating the Confederate States of America and

forcing Missouri to determine its own fate. The state's populace, less

even than that of the Deep South states, could not be divided neatly

into a contest pitting supporters of slavery against antislavery

advocates; the break proved far less clean. Missourians had debated

slavery since its very statehood; in fact, the compromise that bore the

state's name had been the first sectional debate over the peculiar

institution. What threatened Missouri was the question of union or

disunion, whether Missouri should remain loyal to the Union or follow

the course of her "sister states" in the South.

Precisely because they were so accustomed to the slavery debate, most

Missourians were able to remove themselves sufficiently from the

emotion of the slavery question to look at the secession crisis more

objectively than their southern brethren. Though many of the state's

largest and most powerful slave owners called for immediate secession,

most slave-holders feared that, rather than save the

institution, secession would prove its death knell. Thus most

proslavery Missourians were conservative, "conditional Unionists" and

looked upon secession as only a last resort. Yet they also feared the

coercion of the government, demonstrated all too clearly to them by what

they perceived to have been the government's intervention in the recent

troubles over slavery's introduction into Kansas, the first territory to

test the theory of popular sovereignty. Above all, distrustful

Missourians wanted no government intrusion in their reckoning of the

onrushing conflict. One resident perhaps put it best: "We ask nothing

of the gov't at Washington but to be left alone. We need not its

protection—such protection as

the wolf offers the lamb."

|

MEMBERS OF THE KANSAS FREE STATE BATTERY STAND READY TO FIRE THEIR CANNON.

(KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

By contrast, the state boasted perhaps

the most sizable contingent of radical Unionists of any of the slave

states. Concentrated in St. Louis, the state's largest city as well as

the third most populous in the slave states, these "Unconditional

Unionists" largely adhered to the Republican party, the nation's

newest—and preeminent antislavery—party. Joining the

Unconditional Unionists in their support for the Republican party was

St. Louis's German contingent, sixty thousand strong, which represented

the largest immigrant community west of the Appalachians. So devoted to

the cause of the Union were these radicals in St. Louis that of the

27,000 votes Lincoln received in the 1860 presidential election in the

entirety of the slave states, a full 17,028 came from St. Louis. The

onset of the secession crisis caused Union clubs in the city to step

up enrollments, anticipating trouble from the state's disunionists.

As their name suggests, these Missourians, whether Anglo or German,

would defend the federal Union and its government at all hazard.

Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, 1861, coincided with the meeting

of a convention of Missouri delegates in St. Louis elected by its

people to determine the future of their state within the Union. As the

northernmost slave state once Kansas

entered the Union, Missouri was a literal peninsula in the midst of

free soil. With a scant 10 percent of its population being

slaves—the smallest of any slave state save Delaware—and with

only a marginal dependence on plantation crops, the factors influencing

the state's choice differed greatly from those of the Deep South states.

So would the voters' and convention's ultimate decision on secession. So

sure were Missouri's voters of their desire to preserve their connection

to the federal Union that not one avowed secessionist

candidate received election to the convention among the ninety-nine

delegates so elected, and the convention members calmly voted 98—1

in favor of a resolution declaring that "at present there was no

adequate cause to impel Missouri to dissolve her connection with the

Federal Union." Of the eleven slaveholding states that would eventually

call secession conventions, Missouri alone voted to remain in the

Union. Rather, the convention declared the state's neutrality,

attempting to walk a political tightrope, similar to the border slave

states of Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware.

|

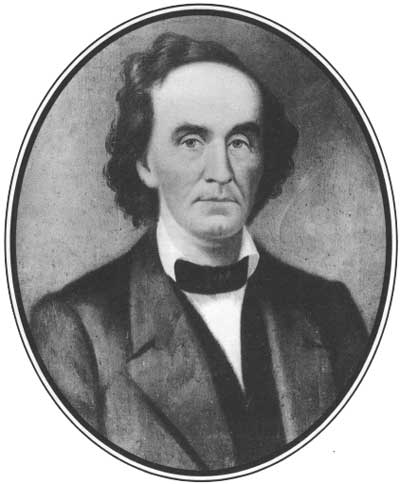

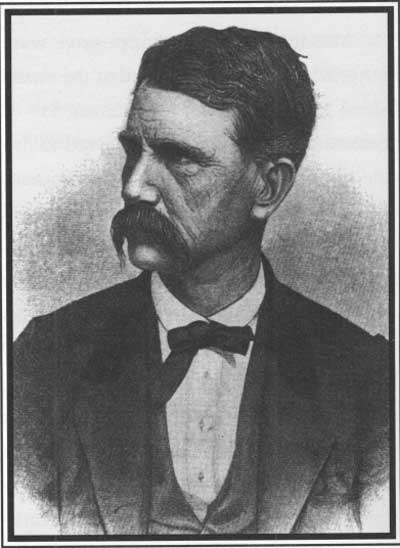

GOVERNOR CLAIBORNE FOX JACKSON (MHS)

|

Despite this clear rejection of disunion, Missouri's new governor,

Claiborne Fox Jackson, inaugurated in January, was working assiduously

to prepare the state for secession. His strategy was savvy; Jackson had

no intention of foisting secession on his Missouri constituents. Indeed,

he recognized implicitly that he had neither the mandate nor the need to

do so. The convention's ringing repudiation of the issue of immediate

secession echoed unmistakably over the state, but even more resonant was

its stand against the federal government's coercion of the states. The

people of Missouri, unlike those in the seceded states, had declared

themselves neither above nor below the Union but equal in stature to it.

Allegiance to their nation came only through its respect for their

state, a distinction Missourians would now demand. Former governor

Robert M. Stewart's appeal to Missourians to maintain their allegiance

to the federal Union through "the high position of armed neutrality" now

actually strengthened his successor's hand in preparing for secession.

Jackson saw rightly that the actions that would prove most singular to

Missouri's course would not be his; rather, they would be the federal

government's.

Jackson now merely needed to maintain fealty to his home state in

order to satisfy these conditions. Should the free states through the

federal government make war on the slave states in an effort to bring

them back into the Union, Missouri's geographical position—it was

now surrounded on three sides by free states—as well as the river

systems it controlled rendered the state a gateway through which troops

would inevitably need to move to reach the Confederacy. In effect,

coercion by military force was inevitable in Missouri. To this end,

Jackson cultivated a public image as the state's indefatigable defender,

Missouri's sentinel, proclaiming his paramount devotion to his state

whenever possible in an effort to crystallize notions of Missouri's

state sovereignty and its potential victimization. Privately, he began

preparing the state for its defense, using "armed neutrality" as a

vehicle for secession. Jackson communicated with disunionists throughout

Missouri, ordered the state's militia commanders to organize camps of

instruction, arranged for heavy artillery from the Confederate

government to capture the arsenal, and assured its president, Jefferson

Davis, that he "look[ed] anxiously and hopefully for the day when the

star of Missouri shall be added to the constellation of the Confederate

States of America." To the chairman of the Arkansas secession

convention, he predicted that "Mo will be ready for secession in less

than thirty days; and will secede, if Arkansas will only get out

of the way and give her a free passage." As Missourians began to

perceive federal plots at every turn, their commitment to the Union

wavered with the passing days. Time clearly was working on the

governor's side.

Missouri's fraying tightrope gave way on April 15, 1861, with news

that the small federal garrison holding Fort Sumter, in Charleston's

harbor, had surrendered to state troops after nearly thirty-three hours

of bombardment. In response, Abraham Lincoln called for seventy-five

thousand volunteers for ninety days of national service to put down the

rebellion in the seceded states "too powerful to be suppressed by the

ordinary course of judicial proceedings." Missouri's quota, reported

Secretary of War Simon Cameron to the state's governor, would be 3,123

men. Claiborne Jackson's response to Cameron was immediate and icily

uncompromising: "Sir: — Your requisition is illegal,

unconstitutional and revolutionary; in its object inhuman &

diabolical. Not one man will Missouri furnish to carry on any such

unholy crusade against her Southern sisters." On the same day that

Governor Jackson responded to Lincoln's call for volunteers, the state

of Virginia seceded. Jackson called for the legislature to meet in

special session on May 2 to take "measures to perfect the organization

and equipment of the Militia and raise the money to place the State in a

proper attitude for defense." Jackson had laid down Missouri's gauntlet,

one that most of its residents as yet wished laid.

|

THE CONQUERING CONFEDERATES SHOWN INSIDE FORT SUMTER ON APRIL 15, 1861. (LC)

|

Immediately, the state exploded in a frenetic series of events.

Buoyed by Jackson's stinging response, proslavery partisanship gave way

in many parts to open secessionism. One observer recalled that in St.

Louis "secession was rampant everywhere. . . . In all places the secesh

were noisy and undisturbed. The enemies of the Government were rapidly

providing themselves with arms and ammunition. . . . To those not in the

secret, it seemed as if secession in Missouri was an accomplished fact."

Meetings held throughout the state's interior called for the legislature

to override the convention's ruling and pass an ordinance of secession,

after erecting southern or secession flags. A miniature Confederate flag

even protruded from a flowerpot that sat on the porch next to Governor

Jackson's front door. Just days after Jackson's response, Missouri

secessionists captured the three-man garrison of the government arsenal

at Liberty, robbing it of a moderate number of muskets, rifles, pistols,

and sabers, as well as ammunition and three six-pound cannon. Another

Missourian proclaimed, "The Secession fever is raging and if Lincoln

shall not stay his hand, the devil himself cant Keep Missouri in the

Union."

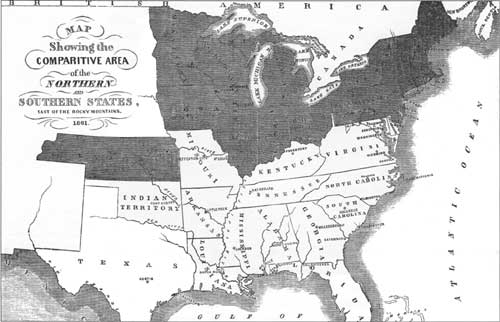

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

A PERIOD MAP SHOWING THE BREAKDOWN BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN STATES.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

Missouri's Unionists, too, quickly became active, perhaps more than

the state's secessionists, and certainly with far greater magnitude.

Nowhere was this more evident than in St. Louis. There, Frank Blair,

Jr., led the effort toward preserving Missouri's adherence to the Union.

Blair, a member of the most influential Republican families in the

country, was a St. Louis congressman and ardent supporter of Lincoln;

indeed, his brother Montgomery was a member of Lincoln's cabinet. With

indefatigable energy, he sought to whip up enthusiasm in the city for

the Union cause by appealing to all elements of Unionist support,

whether radical or moderate. Realizing that to gain St. Louis's full

Unionist support he must enlist more than simply Republican support (the

state was overwhelmingly Democrat), Blair reorganized the former

Republican ward clubs into a more generic Central Union Club, open to

any man who believed in the primacy of the Union and "refusing only to

accept proposals for compromise." Blair further enlisted Germans in

large numbers into paramilitary "Home Guard" companies, drilling in

secret in preparation for Blair's securing arms for them.

|

CONGRESSMAN FRANCIS P. BLAIR, JR. (NPS)

|

|

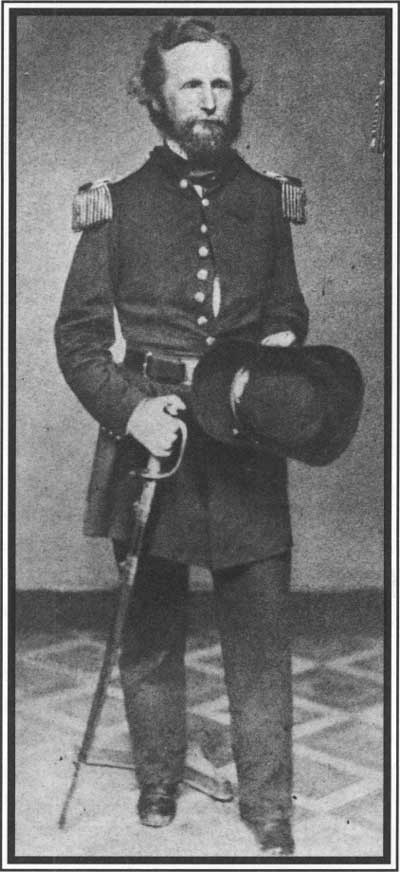

BRIGADIER GENERAL NATHANIEL LYON (MHS)

|

No abolitionist, Lyon saw his transfer to St. Louis in February

1861 as an opportunity to punish the state's secessionists, or, as he

wrote, to "teach them a lesson in letters of fire and blood."

|

To obtain those arms, Blair turned to Captain Nathaniel Lyon, in

command of the small garrison of federal troops defending the St. Louis

Arsenal. Its sixty thousand stand of arms, powder, ammunition,

field-pieces, and arms-manufacturing machinery made it the largest

federal armory in the slave states. Blair found in Lyon an ally as

extreme as himself. Born in Connecticut, Lyon graduated from West Point

in 1841 and had spent his entire career in the army with the Second

Infantry. A rock-ribbed Unionist whose fiery temper, disjointed

religious views, and disrespect for authority had routinely brought on

the enmity of those who served with him, Lyon had distinguished himself

in the Mexican War and received promotion—the only such promotion

of his career—to captain. Early in his career, Lyon proved himself

a martinet whose excessive punishment of enlisted men forced superior

officers to curb his "proclivity to severity." In 1850, while stationed

in California during the hectic days of the gold rush, Lyon led an

expedition that exterminated two entire tribes of peaceful Indians,

totaling four hundred natives, in retaliation for the unrelated

killings of two settlers and an army topographical engineer. Sent to

territorial Kansas in 1854, Lyon saw first-hand the violence there and

matured a hatred for slavery and especially for southern disunionists,

on whom he placed sole blame for the disruption of the Union. While

there, he actively championed the free-state cause, using army troops to

gerrymander elections and assist fugitive slaves to escape, and on one

occasion actually orchestrated the escape of the notorious Jayhawker

James Montgomery, whom he had been sent to arrest. No abolitionist, Lyon

saw his transfer to St. Louis in February 1861 as an opportunity to

punish the state's secessionists, or, as he wrote, to "teach them a

lesson in letters of fire and blood." As much a zealot as an army

officer, Lyon prophesied immediately before leaving Kansas that "I shall

not hesitate to rejoice at the triumph of my principles, though this

triumph may involve an issue in which I certainly expect to expose and

very likely lose my life. We shall rejoice, though in martyrdom, if need

be."

|

|