|

THE FEDERALS ADVANCE

Most saw in their commander visible fatigue, others could "detect

traces of deep anxiety in his countenance and voice. The latter more

subdued and milder than usual."

|

Shortly before his troops' designated hour of departure, Lyon arrived

at Phelps's Grove, the home of Congressman John S. Phelps, where Sturgis

and four thousand troops had been stationed since their return to

Springfield. The troops had been issued cartridges and two days'

rations. Before commencing the march, Lyon addressed each of the

regiments individually. Most saw in their commander visible fatigue;

others could "detect traces of deep anxiety in his countenance and

voice. The latter more subdued and milder than usual." Rather than

encouragement, he offered instructions, telling them, "Don't shoot until

you get orders. Fire low—don't aim higher than their knees; wait

until they get close; don't get scared; it's no part of a soldier's duty

to get scared." Duty and honor, not confidence in them as soldiers, was

the recurring theme as Lyon addressed the various units. Though he meant

his words to bolster his troops, many found them uninspiring, even

"tactless and chilling." The only feeling they seemed to convey was

exhaustion on the general's part.

Striking west, the column soon emerged onto Grand Prairie, with its

rolling fields of grass and scattered trees. The setting sun shone

directly into the soldiers' eyes for a short time, then replaced with

thick dust and gloomy dusk. With the artillery's wheels wrapped with

blankets and the horses' hooves in burlap to muffle the noise, Lyon

personally led the main attack force, organized into three brigades.

Sturgis's First Brigade, which spearheaded the march, was composed of

700 men (including an infantry battalion of regulars who headed the

column and Totten's artillery battery) led by Captain Joseph B. Plummer.

The Third Brigade, which came next in Lyon's column, over 1,100 strong

and including Captain Frederick Steele's battalion of regulars and

Lieutenant John V. Du Bois's four-gun battery, was led by the First

Missouri's Lieutenant Colonel George W. Andrews. The final brigade in

Lyon's column, the Fourth Brigade, with 2,300 men and composed of three

volunteer infantry regiments—the First and Second Kansas, and the

First Iowa—was the Army of the West's largest and was commanded by

Colonel George W. Deitzler. All told, Lyon's column numbered 4,300

effectives—3,800 infantry, 350 mounted men, and 150 cannoneers

manning ten guns.

|

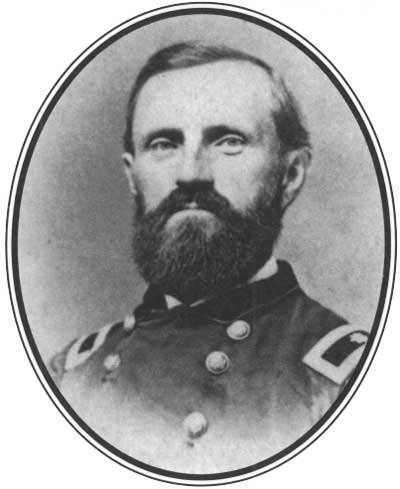

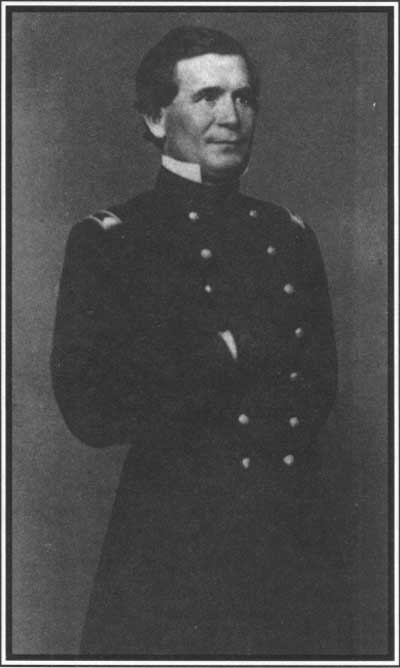

COLONEL GEORGE DEITZLER (GS)

|

Once darkness had fallen, local guides led the federals off the Mt.

Vernon Road and onto local byroads or trails toward a point north of the

Western Army's camps. When the federals halted about 1 A.M., they could

see the glow of the enemy's campfires beyond the hills in the distance.

Surprisingly, they met no outposts. Early on the evening of the August

9, in preparation for the attack on Springfield, the southern pickets

had been withdrawn and had not returned to their posts after rain

postponed the movement. Undetected, the federal column lay down to rest,

waiting for dawn to approach so their attack could be coordinated with

that of Sigel's column.

South of Springfield, Sigel prepared his Second Brigade for the

impending attack. The German's command was composed of three units:

eight companies of Third Missouri Infantry, nine companies of the Fifth

Missouri Infantry, and the six-piece battery of Backofs Missouri Light

artillery. By August 9 the combined regiments were down to only eleven

hundred officers and men, including artillery (many of whom were recent

recruits still learning to drill), having lost as many as three hundred

men on the very eve of the battle, Nearly a third of Sigel's brigade

officers had left their commands.

|

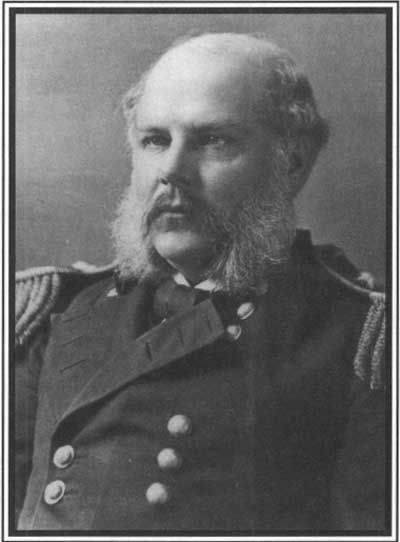

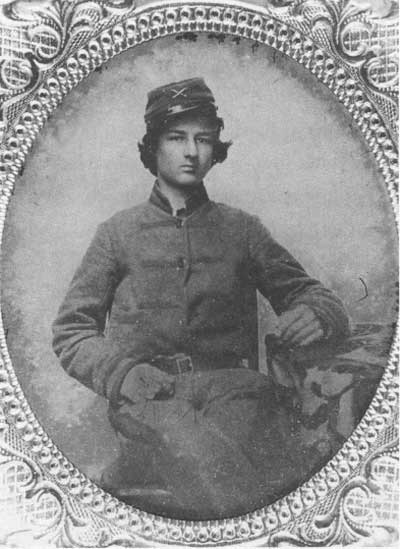

MAJOR JOHN M. SCHOFIELD (NPS)

|

At 6:30 P.M., the brigade marched south out of its camp on the

Yokermill Road, cavalry guarding the head and rear of the column. After

crossing the James River and covering about five miles, Sigel led his

troops southwest through woods and past farms, the rain setting in just

after dark. With almost no moon and under cloud cover, the night was

exceedingly dark and the units moved along only "with great difficulty."

Around 11 P.M., Sigel halted the brigade and remained in position for

three hours, resuming the march at 2 A.M. Sigel's guides led his command

to a point close to Wilson Creek, just below where Terrell Creek joined

the stream and southeast of the southern camps, halting again at around

4:30 A.M. Just before first light, Sigel put his men into motion once

again, climbing a long hill that towered above the creek's east side.

From there, the German had a commanding view of the unsuspecting

southern cavalry camps spread across the wide, flat fields owned by

Joseph D. Sharp, which lay along the creek's west side, a half-mile

south of the main southern camps. His surprise appeared as yet complete.

Unable to communicate with Lyon, Sigel awaited the dawn and the sound of

Lyon's guns, his signal for his own attack.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

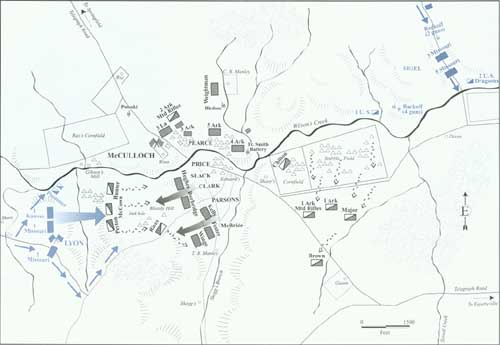

THE BATTLE OPENS AS LYON AND SIGEL ATTACK (5:00-6:00 A.M.)

Lyon's vanguard makes contact with Colonel Dewitt Hunter's Missouri

State Guard Regiment and drives the southerners toward Bloody Hill.

State Guard colonel James Cawthorn then positions McCown's and Peyton's

cavalrymen on Bloody Hill to slow Lyon's advance until reinforcements

arrive. Lyon orders Captain Plummer and his regulars to cross Wilson's

Creek to guard the federal left flank. At the opposite end of the

southern encampment, Colonel Sigel's artillery opens fire on the enemy

encamped at the Sharp Farm. The southern cavalrymen flee from Sigel's

bombardment and Sigel begins his advance.

|

Turning to his chief of staff he remarked morbidly, "I am a

believer in presentiments, and I have a feeling that I can't get rid of

that I shall not survive this battle." A bit later, he added, "I will

gladly give my life for a victory."

|

Far to the north side of the southern camps, Lyon and Schofield

shared a rubber blanket in the light rain. The federal commander

appeared more disconsolate than ever. Clearly, he was not hopeful for

victory and muttered repeatedly about being abandoned by his superiors,

especially Frémont. As Schofield remembered, the Connecticut

Yankee "was oppressed with the responsibility of his situation, with

anxiety for the cause, and with sympathy for the Union people in that

section," lamenting that he "was the intended victim of a deliberate

sacrifice to another's ambition." Turning to his chief of staff, he

remarked morbidly, "I am a believer in presentiments, and I have a

feeling that I can't get rid of that I shall not survive this battle." A

bit later, he added, "I will gladly give my life for a victory."

At 4 A.M., Lyon resumed his advance, marching cross-country through

the tall prairie grass to maintain the element of surprise. Entering a

long, low valley, Lyon sensed that he would soon make contact with

southern troops and deployed a line of skirmishers ahead of the main

column. Nearly immediately, the skirmishers ran into a group of southern

foragers who fired a few shots before running away. Assuming they were

pickets posted to give the alarm, Lyon halted his column and formed its

leading units into line of battle. The march resumed, with the federals

maintaining a fairly rapid pace, encountering no more southerners for

more than a mile.

|

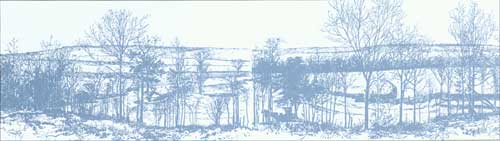

THE BATTLEFIELD AS SEEN FROM BEHIND PEARCE'S CAMP ON THE EAST SIDE OF

THE CREEK. (BL)

|

Lyon's surprise was not complete. The foragers, along with a separate

group of teamsters who had also spotted Lyon's advancing column, had

returned back to their units in Rains's State Guard division and alerted

their respective commanders. Within minutes, Rains ordered couriers to

ride south to inform Price and McCulloch at their respective

headquarters nearer to Skegg's Branch, more than a half-mile away.

Colonel James Cawthorn, commander of the brigade that included the

foragers who had made the initial contact with Lyon's men, dispatched a

mounted three-hundred-man regiment along the west side of Wilson Creek.

When these troops emerged from the ravine and onto the ridge forming the

northern spur of the 170-foot eminence soon to be called "Bloody Hill,"

they could see Lyon's column, not quite 450 yards distant, dismounted

and formed into line. Rather than brush the small force of horsemen

aside, Lyon moved cautiously, deploying his artillery and opening fire

before advancing at approximately 5 A.M. When Cawthorn heard the sound

of firing, he formed the rest of his mounted brigade, at least six

hundred strong, into position on the crest of the main portion of Bloody

Hill to create a second line of defense between the enemy and the

unprotected southern camps. Within a half-hour, the First Missouri on

the right and the First Kansas on the left had moved the half-mile of

rugged slope and pushed Cawthorn from the crest, exposing the Arkansans

camps on the east side of Wilson Creek. Because Bloody Hill was so

broad, they still could view neither Price's headquarters nor the

majority of the camps of the Missouri State Guard and waited for the

rest of Lyon's column.

Despite their early warning, the southern commanders were unprepared

for Lyon's attack. At dawn, Price had sent an adjutant to McCulloch's

headquarters to learn his plans for the advance on Springfield.

McCulloch failed to inform the adjutant that several minutes earlier he

had received word from Rains claiming enemy activity to the north. After

sending two cavalry units to investigate, McCulloch decided to confer

with Price in person. He left his headquarters around 5 A.M., and rode

south to Price's headquarters, at the farm of William Edwards, just as

Lyon's troops were engaging the State Guard on the northern spur of

Bloody Hill. As McCulloch and Price ate breakfast, one of Rains's

adjutants rode up and announced that federals were "approaching with

twenty thousand men and 100 pieces of artillery." When a second

messenger arrived from Rains, announcing that "the main body of the

enemy was upon him," both Price and McCulloch set out to survey the

situation at the northern end of their encampment. They soon heard the

sound of cannon.

|

CAPTAIN JAMES TOTTEN (USAMHI)

|

|

AN UNKNOWN PRIVATE OF THE PULASKI BATTERY (GS)

|

As Lyon's Missourians and Kansans, now joined by the First Iowa, on

Bloody Hill engaged Rains's troops, Totten arrived and deployed his guns

in between them, and both infantry and the artillery opened fire. They

soon cleared the crest of the hill of southerners, and as Lyon waited

for the rest of his line to deploy, Woodruff's Pulaski Arkansas Battery

opened on him. Positioned on a lightly wooded ridge that paralleled the

Wire Road on the east side of Wilson Creek, the Arkansans, under Captain

William Woodruff, saw Lyon's two batteries deploy on Bloody Hill, more

than half a mile away. As he watched the Missouri State Guard being

driven off the hill by the federals, Woodruff began firing. The unit's

two twelve-pounder howitzers and two six-pounder guns roared into

action, effectively enfilading Lyon's advance. Totten's federal

artillery immediately wheeled to target them, and soon shells screamed

back and forth, high above and across Wilson Creek. The effectiveness of

Woodruff s battery slowed Lyon's deployment, allowing the southern

troops—which Lyon could not yet see—to form and advance to meet the

stalled federals on Bloody Hill. The battle would soon join, the firing

so intense that it was heard as far away as Springfield.

|

|