|

THE ADVANCE AND ROUT OF SIGEL

As dawn broke, Sigel began positioning his brigade on the extreme

south of the field, He ordered four guns from Backofs Missouri Light

Battery deployed on the 150-foot knoll that shielded him from the

southern camps below and from which he would bombard the camps. He sent

the rest of the infantry and the remaining section of artillery down the

ravine toward the cleared fields, posturing them to block the Wire Road

in the rear of the southern army. At about 5:30 A.M., Sigel first heard

the sound of Lyon's musketry from the north. At this signal, he began

bombarding the southern cavalry camps.

|

CAPTAIN JOSEPH PLUMMER (NPS)

|

Cavalry units from all three components of the Western Army, totaling

over 1,800 men, were encamped in Joseph Sharp's fields. From the

Confederates, Colonel Elkanah Greer's South Kansas-Texas Cavalry,

approximately 800 men, along with a company of horsemen from Arkansas,

probably numbering less than 100 men, camped with the Texans. Colonel De

Rosey Carroll's First Arkansas Cavalry, belonging to the Arkansas State

Troops, had 350 men, while two units from the Missouri State

Guard—numbering nearly 600 horsemen—were present. Unlike Lyon,

Sigel's surprise was indeed complete, and his cannonade produced

immediate chaos. While some of the cavalry maintained some semblance of

discipline, moving away from the guns, others fled into the woods to the

north and northwest of the fields and took no further part in the

battle. Completing the mayhem was the presence of the almost 2,000

unarmed Stare Guardsmen and untold numbers of camp

followers—slaves, women, and perhaps even children—who had

accompanied the Western Army despite McCulloch's demand that they remain

well behind. Most of them were apparently camped on the Sharp property,

and they scattered in terror when Sigel's guns opened upon them.

Seeing the mass of confusion below, Sigel ordered the Third and Fifth

Missouri, with cavalry in the lead, to advance, They crossed Wilson

Creek at a ford and climbed up onto a small plateau, followed closely by

the artillery. The land was cleared and fenced in, so the advance was

rapid with little resistance from the few remaining southern troops.

While the four guns from the Missouri Light Battery continued their

barrage, Sigel's horsemen captured more than 100 prisoners as they

pushed forward quickly into the evacuated cavalry camps in the Sharp

fields, where deserted campfires, equipment, wagons, and picketed horses

remained just as they were abandoned. Lulled into complacency, Sigel

ignored the possibility of a counterattack against his exposed column

and ordered his men to rest on the road for nearly an hour. When what

appeared to be a regiment of the enemy rallied, Sigel at last put them

into a line across the stubble field, placed his guns in the center, and

at 7:15 A.M. opened artillery fire again on troops in the woods to the

north. Within half an hour, the southerners had fled again into the

woods lining Wilson Creek, and Sigel halted the cannonade. Now

overconfident, the German put his men back into column and moved past

the Sharp house to the Wire Road, which ran to its immediate front,

deploying a four-gun battery in the farmhouse's front yard. With only a

single battalion of the Third Missouri (some of the least experienced

men in the brigade), perhaps 250 men in all, in line to the right of the

battery, Sigel left the remainder of his force in reserve astride the

Wire Road. They waited to pounce on the main body of the Western Army,

which Sigel believed Lyon would soon be driving his way.

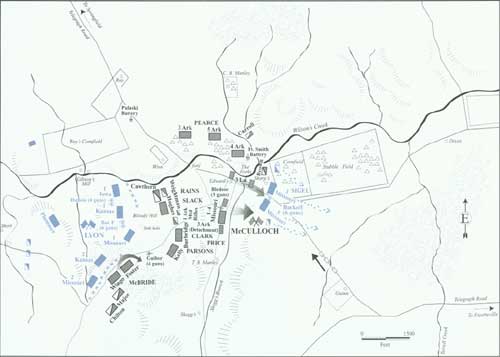

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

LYON AND PRICE BATTLE ON BLOODY HILL AS SIGEL IS ROUTED

(7:30-8:45 A.M.)

By 8.00, McBride's attack on the Union line is over and his troops have

withdrawn. A brief lull ensues as Price prepares to mount a larger

assault on Bloody Hill. At the other end of the battlefield, Sigel forms

his brigade near the Sharp House to block the Wire Road. General

McCulloch leads the Third Louisiana Regiment to meet Sigel, aided by

Missouri and Arkansas infantrymen, Bledsoe's Missouri Artillery, and

Reid's Fort Smith Battery. The concentrated fire of these southern

troops routs Sigel's men from the field.

|

By 8:30 A.M., squads of unarmed southern soldiers streamed south on

the Wire Road, surrendering to Sigel's men as soon as they emerged from

the trees in the valley below. Sigel believed that his battle plan was

working to perfection and that he would soon be the hero of this

imminent victory. Bolstering his overconfidence, he also thought he

spied a large number of southerners moving south along the ridges east

of the creek and assumed Lyon was driving McCulloch's army from the

field into what the German considered a well-laid trap. He sent only a

few of skirmishers into the woods in his immediate front, leaving his

column dangerously vulnerable. The mistake would soon prove costly.

The troops that Sigel thought he saw were four hundred men from the

Third Louisiana, rallied near the Ray house after their disorganized

retreat following their pursuit of Plummer. McCulloch was searching for

troops to move against Sigel on the south end of the field, having

learned that the Western Army's right flank was now secure. Seizing the

initiative, McCulloch took command of the nearest two companies and led

them south on the Wire Road and across Wilson Creek. McCulloch sent word

to McIntosh to bring as many of his troops as possible down the Wire

Road with all haste. Within minutes, McIntosh received McCulloch's

missive and took charge of the column of several hundred, hurrying it

southward on the Wire Road, pausing only to fill canteens when the men

crossed Wilson Creek. When McCulloch and the two lead companies reached

Skegg's Branch, they met Sigel's skirmishers, who immediately retired.

They informed Sigel that Lyon's men were coming up the road, mistaking

McCulloch's column in the smoky haze of the trees. Sigel's surgeon, Dr.

Samuel Melcher, suggested that Sigel display the national flag

conspicuously, to avoid friendly fire. Sigel cautioned his artillerymen

not to engage the troops that would soon appear in their front as one of

the Union color-bearers advanced and waved the flag. Finally, Sigel

dispatched a soldier to walk down the Wire Road and challenge any

approaching troops.

|

COLONEL JAMES MCINTOSH (NPS)

|

McCulloch used the opportunity to deploy his two companies, as well

as those under McIntosh, who had caught up to the lead column, into line

of battle, with the foliage, smoke, and the slope shielding the entire

movement. Joined on the right by a force of State Guard, McCulloch

stopped the lone federal scout as he approached his line of battle. When

the soldier raised his musket after identifying himself, one of

McCulloch's men killed him, preventing him from spreading the alarm to

Sigel's waiting troops. The Texan then ordered his men to advance.

As many as a third of these federals, most of whom were poorly

trained recruits, fell immediately, while many others including Sigel

hesitated to return fire, believing they were victims of mistaken

identity.

|

When the southern line reached the edge of the plateau, forty yards

from the federal line, Sigel's color-bearer was waving the United States

flag. Artillery fire erupted almost simultaneously from two southern

batteries, and two of the guns from Backofs battery replied at once.

Shielded by the lip of the plateau, the Louisianans quickly stepped

forward to the edge of the plateau and delivered a direct volley into

Sigel's men at almost point-blank range. The tables had now turned on

Sigel, whose men were completely surprised. As many as a third of these

federals, most of whom were poorly trained recruits, fell immediately,

while many others—including Sigel—hesitated to return fire,

believing they were victims of mistaken identity. Because neither army

wore standard colors or style of uniform and because Sigel's men

anticipated the arrival of Lyon's forces, many assumed the gray-clad

Louisianans were members of the First Iowa, which possessed several

companies wearing gray. The mistake was catastrophic.

By the time Sigel understood the gravity of the situation, it was too

late. Some federal soldiers returned fire, but others refused, unwilling

to believe they faced enemies. Because the bulk of Sigel's command was

not in line, no effective demonstration was possible, despite a

three-to-one superiority in manpower. While Sigel finally attempted to

rally the men and return fire, his brigade disintegrated, with men

fleeing and abandoning the four guns and one of the caissons. The entire

flanking force dissolved into a rout. The Louisianans quickly captured

the four artillery pieces astride the Wire Road. At the same time, the

left flank of the southern line reached the northern edge of Sharp's

fields and began firing at the fleeing enemy.

|

THIS HARPER'S WEEKLY ILLUSTRATION FROM AUGUST 1861 DEPICTS THE

FIGHTING AT WILSON'S CREEK. (FW)

|

Southern cavalry units soon took up the chase, but the effort was

never coordinated. Because the federals scattered in two directions (one

to the south, as they had approached; the other southwestward along the

Wire Road), they proved difficult to capture. Sigel led about 250 men

back toward Springfield, along with one cannon, and they were attacked

by several battalions of southern horsemen at the ford of the James

River, scattering to the woods and fighting back desperately. Sigel

himself narrowly escaped capture by hiding in a cornfield with one of

his men; he arrived back in Springfield at 4:30 P.M. By the time the

running fight was over, more than 64 federals were killed and another

147 were captured, along with another brass six-pounder, two caissons,

and the colors of the Third Missouri. Southern losses were negligible.

The threat to the rear of Price's troops ended with the inglorious rout

of Sigel's column. Now the Western Army could turn its full attention to

Lyon on Bloody Hill.

|

A SCENE OF HORRORS: MEDICINE AT THE BATTLE OF WILSON'S CREEK

Just before the break of dawn on August 10, the Battle of Wilson's

Creek commenced. Before noon there would be 1,818 wounded and 535 dead.

The physicians of both armies began the urgent process to gather, treat,

and evacuate the wounded. Many of the wounded had to find their way to

wherever the surgeons had established their medical facilities. In some

areas there were aid or dressing stations where the wounded were given a

cursory examination and stabilized. Blood flow was stanched, broken

bones immobilized, and stimulants given to counteract shock. They were

brought from these stations or went directly to field hospitals where

further treatment was given.

The federals established their field hospital in a ravine just north

of Bloody Hill, out of the danger of musket and artillery fire. There

were no amputations or other more extensive surgery performed at this

field hospital; this was to be left to the general hospitals in

Springfield. Assistant Federal Surgeon Davis wrote, "The wounded could

not be evacuated to Springfield during the battle because of the

severity of the engagement and the constant changing of position of the

troops. The fluidity of the battle kept the ambulances and wagons parked

in the rear, guarded by cavalry, while the wounded lay suffering only

400 yards away."

|

LIEUTENANT OMER WEAVER, A MEMBER OF THE PULASKI BATTERY, WAS KILLED IN

ACTION AT WILSON'S CREEK. (ARKANSAS HISTORY COMMISSION)

|

Union general Lyon was faulted for not having a medical director to

oversee the federal surgeons on the field. One of the surgeons wrote,

"The regiments had no community of action or feeling." In other words,

they did not act as a team. A medical director would have removed the

wounded from the field in a more efficient manner. When heavily engaged,

the regimental surgeons were too busy with men falling around them to

worry about what was going on with the regiments on the rest of the

battlefield. The southern surgeons were no better. There is no record of

a southern medical director being present.

The surgeons of the southern forces established their own field

hospitals located at various sites about the battlefield. Here major

surgery was performed while the battle raged around them. These included

a site of previous church revivals west of Bloody Hill, another near the

junction of Wilson's Creek and Skegg's Branch, and at the Edwards Cabin,

General Price's headquarters. With the fighting in Ray's cornfield

reaching its climax, Confederate medical officers commandeered the

nearby Ray house for the care and treatment of the wounded. Tents in the

southern camps were also used.

Dr. W. A. Cantrell of Churchill's First Arkansas Mounted Rifles

wrote, "In the beginning of the battle, I was amidst the hottest of the

time, and thought at one time I could not escape death. Balls from two

thousand guns and one battery of cannon were flying thickly around

me—here and there a man or horse would fall, some wounded others

dead. . . . The battle raged four or five hours—hard fighting all

the time. My work began soon after the first round or two of musketry.

The wounded were then brought to me, and from that moment to the present

time, I have seen or heard nothing but gun shot wounds and the groans of

the dying and the distressed."

The walking wounded or the wounded carried by comrades on makeshift

stretchers made of blankets could, with difficulty, reach the field

hospital. The seriously wounded lying on the battlefield away from the

aid station or field hospital had to endure the danger of another wound

if they lay in the line of fire coupled with the humidity and the

terribly hot August sun.

|

DR. SAMUEL H. MELCHER (BL)

|

Dr. Caleb Winfrey with the Missouri State Guard had his horse and

buggy on the field. He was one of the few surgeons giving aid to the

wounded on the battlefield while the battle raged on around him. After

the battle he operated at the Ray house until well into the next day and

left with them for Springfield.

Shortly after 11 A.M. Major Samuel Sturgis, who had assumed command

of the federal forces after General Lyon's death, gave the order for the

wounded to be taken to the hospital ravine in preparation for retreat

back to Springfield. The small number of ambulances and wagons were

quickly filled. Out of necessity the wounded were loaded onto artillery

caissons for the painfully jarring ride in 100 to 108 degree

temperatures.

For days hundreds of the federal wounded were left behind on the

battlefield. Fearing that more transportation would be needed for all of

the wounded, federal officers ordered every usable vehicle commandeered

and sent back to Wilson's Creek. Soon farm wagons, buggies, carriages,

even butcher's wagons were sent hurrying down the Telegraph Road.

Meanwhile the southern forces were doing their best to treat their

own wounded. Parties of men were organized to bring in the casualties.

The heat was unbearable to these men. One Missourian reported, "The

thirst that the wounded suffered that day was fearful." Dr. John Wyatt

of the Missouri State Guard and federal surgeon Dr. Samuel H. Melcher

were horrified by the condition of some of the patients. Wyatt wrote: "I

saw blow flies swarm over the living and dead alike. I saw men not yet

dead their eyes nose and mouth full of maggots."

Slowly the stream of wounded federals found its way back to

Springfield. Surgeons began the monumental task of repairing the damage

done by weapons of war. After the wound was inspected and the nature of

the operation determined, the patient was rendered unconscious by the

administration of a general anesthetic. Ether and chloroform, the latter

drug the newer of the two agents, had been introduced during the

previous decade. Chloroform was the anesthesia of choice of field

surgeons since it acted quicker and required smaller amounts than that

ether. It was also safer to use around an open flame.

The ideal time to amputate was in the first twenty-four hours after

receiving the wound. After 24 hours the mortality and morbidity rate

would quickly rise. The mortality rate from infection was high since

nothing was known about the cause of infection until after the

publication of Lister's work in 1867.

|

MAJOR SAMUEL STURGIS (NA)

|

Fearing that the victorious southern army was at that moment

advancing on Springfield, the federals began the retreat to Rolla,

Missouri. By dawn of the eleventh, the only federals left were several

surgeons and the wounded who could not travel and those left behind

because of the scarcity of wagons.

Despite conflicts over scarce resources, southern surgeons assisted

their Union counterparts in treating the federal wounded. One southerner

noted, "The Federal wounded are taken as good care as our own, though

that is not the best, medicine being scarce." Local ladies also visited

the hospitals, assisting in any way they could. "The fair sex, God bless

them," wrote Missouri State Guard surgeon Wyatt, "[They] are doing all

they can in the ways of cooking, serving, mending, and nursing the sick

and wounded."

The casualties from the Battle of Wilson's Creek would remain in

Springfield recuperating from their wounds for several more months.

— by Kip Lindberg and Thomas P. Sweeney M.D.

|

|

|